On March 26, the Chicago district of the National Labor Relations Board ruled in favor of the players of Northwestern University’s football team, giving them the right to form a union over the objections of school administrators. The decision raises the specter of a future in which March Madness is cancelled due to player strikes.

The National Labor Relations Board is a quasi-judicial body, so the question of whether NCAA athletes can form unions will likely be decided by an appeal in court. Northwestern expressed its disagreement, saying in a statement that “Northwestern believes strongly that our student-athletes are not employees, but students.” The NCAA echoed the line, adding, “We strongly disagree with the notion that student-athletes are employees.”

“Student-athlete” is a staple of NCAA statements, often accompanied by the sentiment expressed by Northwestern’s football coach in court, “We want [our players] to be the best they can be… to be a champion in life.” It’s a high-minded ideal. It’s also a term invented by the NCAA in the 1950s to avoid legal liability for athletes’ injuries. Author and historian Taylor Branch writes in The Atlantic:

“We crafted the term student-athlete,” [former NCAA executive director] Walter Byers himself wrote, “and soon it was embedded in all NCAA rules and interpretations.” The term came into play in the 1950s, when the widow of Ray Dennison, who had died from a head injury received while playing football in Colorado for the Fort Lewis A&M Aggies, filed for workmen’s-compensation death benefits. Did his football scholarship make the fatal collision a “work-related” accident? Was he a school employee, like his peers who worked part-time as teaching assistants and bookstore cashiers? Or was he a fluke victim of extracurricular pursuits? The Colorado Supreme Court ultimately agreed with the school’s contention that he was not eligible for benefits, since the college was “not in the football business.”

A natural assumption is that a union would demand pay and professional contracts. The small elite of college athletes that compete in NCAA football’s BCS bowl games or basketball’s March Madness power an industry that brings in comparable ad revenue to their professional counterparts. It seems absurd to call them amateurs — or to ban them from selling a signed jersey when the school shop sells thousands of them.

A central premise of the Northwestern players’ case was that their scholarships constitute pay. And Northwestern quarterback Ken Colter says that players are already paid in the form of a scholarship. So wages and contracts may or may not be a demand of a student-athlete union. But if not wages and a piece of the NCAA’s billions, what should college athletes collectively bargain for? Below we explore some possibilities beyond pay.

1) Guaranteed 4 year scholarships. Since 1973, the NCAA has banned all but one year scholarships. This means schools can effectively cut players between seasons, and new college coaches do replace scholarship players with recruits of their own. Given the challenge of balancing athletics and academics, scholarships that extend a year beyond a player’s eligibility, giving them a final year to focus fully on academics, would be ideal.

2) Better medical care. Last year, the New York Times reported on the situation of Valerie Hardrick, who received a $10,000 bill for an MRI performed on her son, a basketball player at Oklahoma. Similarly, Kent Waldrep, who was paralyzed from the neck down while playing running back at Texas Christian University, relied on charity to pay his medical bills when TCU stopped paying them.

The NCAA has avoided standard workers’ compensation regulations by pointing to athletes’ amateur status, but that shouldn’t keep teams from covering medical bills. The NCAA only requires that athletes have an insurance policy like any regular student. Expanding the NCAA’s (currently limited) catastrophic insurance coverage and mandating that schools cover all sports-related injuries are good candidates for changes.

3) Action on debilitating head injuries. Northwestern quarterback Ken Colter has cited this as the type of “basic right and basic protection” the players seek. Former college football players have filed lawsuits against the NCAA for ignoring the risks of concussions and head trauma, but a union would give them a voice in setting current policies. Without the power of collective actions, players are at the whim of an organization with 8 billion reasons to ignore head trauma.

4) Fewer Practice Hours. In his testimony, Colter testified that he devoted 40-50 hours a week to football and could not pursue his preferred pre-med major due to athletic requirements. This contradicts the NCAA’s own 20/8 rule, which limits student-athletes’ time commitment to 20 hours a week in-season and 8 hours a week during the off-season.

Universities circumvent the rule by holding optional sessions that no player would dare miss, and most athletes are unaware of the rule. Even if the time requirement remains high — and many players want to be devoted to their sport — players could at least ensure that future players in Colter’s position have the option to prioritize class.

5) Stipends. Critics of the NCAA point out that athletes’ “full scholarships” provide $3,222 less per year than the real cost of their education and leave 85% of student-athletes living under the federal poverty line. The NCAA has considered allowing a $2,000 a year stipend for players; a union could ensure players are financially secure during college.

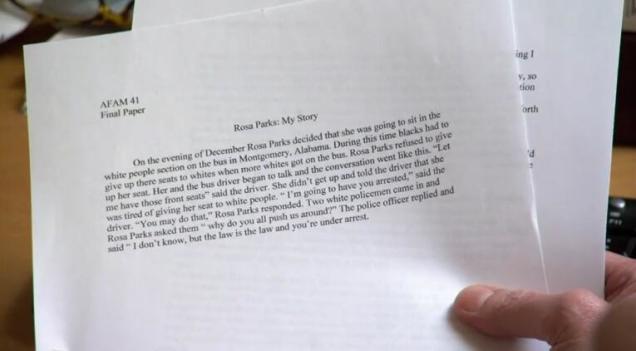

6) Real academic support. In the latest academic scandal at a big time athletic college, whistleblowers revealed the prevalence of fake classes (described officially as “independent studies”) offered to athletes at UNC. The students never attended class and received assistance to write papers like the one below, which received an A minus.

Football player Deunta Williams told the media that advisers meant to give athletes academic assistance pushed them toward the classes. “His job was to keep me eligible,” he says. Learning specialist Mary Willingham described a significant number of students as reading at an elementary or middle school level. She noted that the transcripts of athletes, which obviously showed their grades propped up by “independent studies,” were certified by the NCAA. “I’m told everyone does it,” she related. “We cheated [these athletes] out of what we promised them: a real education.”

The NCAA responds to calls for college athletes to be paid by pointing out that 99% of athletes will not go pro and that the current system has helped thousands of students attend college. But they’re clearly failing at providing an education. The president of the National College Players Association, which assisted the Northwestern players with their case, said after the unionization decision:

“After a decade of advocacy, I’ve tried every other way. We’ve begged, pleaded, pressured, changed laws. There is no other way to bring forward comprehensive reform, and just like other billion-dollar industries, the answer is a union.”

The adults in the NCAA and at universities seem too caught up in March Madness and million dollar ad buys to ensure athletes get a real education. Now its up to the players.

This post was written by Alex Mayyasi. Follow him on Twitter here or Google Plus. To get occasional notifications when we write blog posts, sign up for our email list.