The Olympics is a rarity in the sporting landscape. In general, women’s sports are relegated to minor channels or ignored entirely. SportsCenter devotes 1.4% of air time to women’s athletics, which receive about 4% of all sports air time in America. Yet every two years, millions watch female Olympians compete in primetime television. And a select few — like hurdler and bobsledder Lolo Jones — enjoy Tom Brady level media coverage, star in national promotions, and become household names.

This has not protected the Olympics from charges of sexism. A recent Atlantic article rounded up plenty of tweets from viewers upset with broadcasters for referring to female Olympians as “girls.” Others note that athletes feel pressure to look good during competition in order to win coverage and sponsorship deals: One skier described prepping her makeup for 30 minutes just to prepare for interviews once she removes her helmet after a run. And they must do so at the risk of backlash like that faced by Lolo Jones during the 2012 Summer Olympics when a Times writer opined:

Jones has received far greater publicity than any other American track and field athlete competing in the London Games. This was based not on achievement but on her exotic beauty and on a sad and cynical marketing campaign. Essentially, Jones has decided she will be whatever anyone wants her to be — vixen, virgin, victim — to draw attention to herself and the many products she endorses.

As the Sochi games come to a close, new analysis of the 2012 London Summer Olympics offers some hard data on the Olympic Games’ treatment of female athletes. In 2012, the women of Team USA dominated, winning 58 medals, including 29 golds. Investigating whether the Olympics achieves the type of parity envisioned by Title IX, the authors of “(Re)Calling London: The Gender Frame Agenda within NBC’s Primetime Broadcast of the 2012 Olympiad” find encouraging, if uncertain, signs that they also won equal treatment.

“History is Written by Those with Television Rights”

No women competed in the first modern Olympics in 1896. The founder of the International Olympic Committee believed “The only real Olympic hero… is the individual adult male. Therefore, no women or team sports.”

In contrast, women made up 41% of the athletes in Vancouver’s 2010 games and 44% of participants in London’s summer games.

The crux of the analysis in “(Re)Calling London” is that the nearly equal number of male and female Olympians that compete today does not mean that each gender receives equal treatment. NBC, the sole broadcaster of the Olympics in the United States, covers only a small percentage of the Games. By looking at which sports NBC broadcasts during its primetime coverage, and how it covers sports of each gender during that time, the authors examine how viewers experience female sports during the Olympics. And as NBC strives to satisfy audiences, those choices also represent (to a degree) American preferences.

The research team began by measuring the amount of primetime coverage devoted to male and female sports. Analyses of past Olympics have revealed that women receive less air time than male Olympians, although the ratio is more equitable during Summer Games than during Winter Games. (The deficit during the summer games is only 6-8%, which is actually less than the participation gap between men and women in those Olympics.)

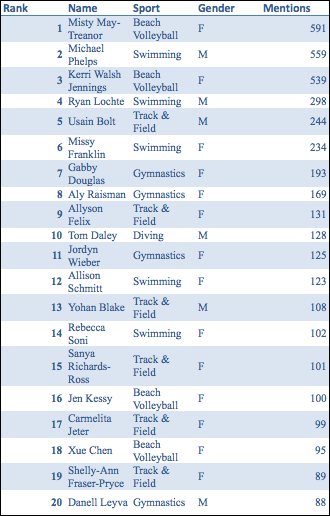

To the researchers’ surprise, they found that women received 54.8% of NBC’s primetime coverage. The team also counted the number of times a reporter or commentator said the name of each athlete during its primetime coverage and found that women took 14 of the top 20 “most mentioned” spots. Female athletes overall received 392 mentions per primetime broadcast to men’s 340.

But not all the results were so feminist pleasing. Hosts like Bob Costas mentioned male athletes more than female Olympians, and the number of mentions is skewed by how often announcers say athletes’ names during play-by-play. The high number of mentions of Misty May and Kerri Walsh, for example, may reflect the fact that volleyball announcers constantly say the players’ names more than it reflects the relative attention paid to their success on the court.

One way to avoid this complication is to compare the number of pre-produced spots aired about male versus female athletes. Here the record is again mixed. NBC promoted the Games with commercials featuring female athletes like May and Walsh exactly once more than they did with spots featuring Michael Phelps or other male Olympians. During the Olympics coverage itself, however, NBC played 1.5 times as many profiles of male athletes.

Similar to the viewers criticizing the 2014 reporters for calling female athletes “girls,” the researchers also looked for differences in how the reporters described male and female Olympians. The team identified all the adjectives and descriptive terms used to describe athletes and grouped them into 16 categories such as concentration, strength, attractiveness, size, and background.

Comparing the frequency of different terms by sport, the researchers found that the announcers explained men’s success more often as driven by experience. Women’s success or failures were described as a result of composure or consonance (like a “tough break”) more often than men’s. In terms of general descriptions of the athletes, women received more comments about their emotions and appearance.

Some of these results sound like indications that announcers described female Olympians in a different, perhaps stereotypical, manner. But the authors caution that similar analyses of past Olympics don’t reveal the consistent patterns we might expect of stereotypical commentary. So while the increased prevalence of comments about female athletes’ composure and emotions could indicate a stereotype, it is not a difference seen in past Olympics. Similarly, the 2004 broadcast more frequently ascribed male Olympians’ success to “courage” than it did for women, but in 2006 and 2010, “courage” was more often used to describe female athletes.

Even appearance, the top complaint about a double standard for women, was brought up more often about female athletes in the 1994-1998 games, but not from 2000-2010. And the researchers’ findings of a gender disparity about attractiveness in the 2012 games represented only 14 total comments. If commentary of women’s olympic events are ruled by stereotypes, it doesn’t appear to be in a manner consistently picked up by academic studies of the Games.

Professional Powderpuffs

The United States actually has four women’s football leagues. Three of them look like miniature NFLs, played with identical rules to the National Football League’s. Unlike the NFL, though, the sport is 100% passion. The games bring in sparse sponsor or television money, so players need to pay for the privilege of competing.

The head of the oldest league, the Women’s Football Alliance, finds it unfortunate that professional women’s football still needs to charge a training fee. She also has another complaint:

It is also disheartening that the media readily covers women’s tackle football as long as the women are playing in their underwear.

She is describing the Lingerie Football League, recently rebranded as the Legends Football League, which originated as a pay-per-view Super Bowl Halftime special and still unapologetically dresses its players in only bras, underwear, helmets, and shoulder pads.

Despite the uniforms, the competition is serious. One football fan complimented Dallas Desire quarterback Linda Brenner for “hurl[ing] a tight spiral 45 yards on a rope.” But good looks are a requisite. Commissioner Mitch Mortaza told ABC News:

“We just happen to have an entire league of Tom Brady’s and David Beckham’s and Maria Sharapova’s. That’s the business model. We’re very upfront and honest about it.”

At least by the quantifiable data, American coverage of the London Olympic Games was fairly equitable. And in many ways this is an accomplishment of Team USA’s women who, as the authors note, put in an incredible performance, outearning both American men and nearly every country in the world in the medal count. In future games, we may not consider a 50-50 split in coverage equitable given American women’s Olympic dominance.

Yet that success remains in many ways gendered. The majority of primetime coverage goes toward less than 10 sports. For women, gymnastics and beach volleyball accounted for the majority of the 2012 prime time. On one hand, this represents NBC sticking to its alibi of covering the biggest stories: The women’s gymnastics team engaged in a furious rivalry with China, while Misty May and Kerri Walsh won their 3rd straight beach volleyball gold to cement their status as the best ever in their sport. On the other hand, both sports are often considered “feminine” or acceptable for women and involve the sex appeal of women competing in bikinis or leotards.

So while there’s encouraging news for advocates of female athletics, there are still plenty of signs that female Olympians could face the dynamic running through women’s football in America: They are all serious competitors, but the women with good looks and/or the willingness to go along with “sex sells” marketing campaigns receive more media attention, coverage, and sponsorship dollars. Lolo Jones, the hurdler turned bobsledder who received the ire of a Times writer as described above, explained in an ESPN documentary why she plays up image for sponsors:

“I have a chance to get sponsors every four years, and that money has to last. If you know anything about the Olympics, in between—those four years in between—it’s like the desert [financially speaking].”

Of course, good looks are not irrelevant for male athletes. In a perfect world, we could create an alternative universe where both Misty May and Ryan Lochte have unibrows, and measure the resulting drop in their coverage and sponsorship deals. But the dynamic seems much stronger, and inevitable, for female Olympians.

Those who argue that professional sports are a free market will not necessarily consider gender disparities and female athletes’ need to market their sex appeal as a problem the way advocates of women’s athletics do. But the coverage of professional sports has a powerful effect on those watching. As we have covered previously, the success of Anna Kournikova and golfer Se Ri Pak led to a surge in the number of Russian girls in tennis academies (and women in the Women’s Tennis Association Top 100) and South Korean girls playing golf (and eventually making the LPGA).

The Olympics are an anomaly. They have a more female audience than just about any sporting event in the world (that NBC then caters its broadcast to) and leads viewers to more readily watch female sports as audiences often care more about watching their own country compete than the gender of the athletes. So even perfect parity in the Olympics may not mean much for women’s athletics elsewhere. But given the power of high-profile examples, the prominence of female Olympians could have a huge impact on women’s sports.

This post was written by Alex Mayyasi. Follow him on Twitter here or Google Plus. To get occasional notifications when we write blog posts, sign up for our email list.