Think about how much you hate jury duty and the lengths you would go to avoid it. That’s how desperate American businesses are to avoid courtrooms and lawsuits.

That is because court cases are slow, costly, and at times inexplicable. The average civil trial (non criminal case such as a breach of contract or discrimination suit) takes just over two years to complete. Even small trials in which less than $10,000 in damages are at stake still stretch over 21 months. A recent study estimated the cost of resolving an “average” automobile case at $43,000 in legal fees. An employment dispute averages $88,000, a contract dispute $91,000, and a malpractice suit $122,000. Fortune 200 companies spend $115 million each on annual litigation costs. On average their legal bill represents half a percent of their domestic revenue – while they spend only .06% of foreign revenue on litigation costs.

The worst threat, however, the sword of Damocles dangling over businesses, is the possibility of facing punitive damages. Judges and juries force defendants to pay monetary compensation to successful plaintiffs. But in cases where they decide that merely paying compensation will not prevent the guilty party from breaking the law again, they may force the company to pay additional “punitive” damages. When the intent is to send a message to a company, punitive damages can be extremely high. Stories like that of a woman who sued McDonald’s for $2.7 million for spilling hot McDonald’s coffee on herself worry executives.

Over the past two decades, businesses have embraced arbitration as a way to avoid courtrooms. If parties to a legal dispute agree to it, they can choose arbitration as an alternative to a trial. They hire someone, often a retired judge who works for a private arbitration firm, to hear the merits of a case and make a decision that is enforceable in court. Without the need to wait months for a court date or hear lawyers argue endlessly about proper legal procedure, arbitration promises a swifter and cheaper resolution to legal disputes than a courtroom.

In Silicon Valley, most employment contracts have an arbitration clause, cursorily listed along with agreements to not disclose third party information or assist competitors. Signing an offer letter signifies agreeing to resolve any dispute, whether it be a disagreement over pay or an accusation of discrimination, with an arbitrator instead of a court. Given the level of trust and the value many employees have to their companies in the Valley, few people question it.

But arbitration clauses are standard in contracts where there is much less trust and equality. About one fifth of employee contracts, many in environments that are more class struggle than chummy, feature such clauses. Most car dealerships includes arbitration agreements in every sale contract. Banking, credit cards, and home building are all industries where arbitration clauses are common if not universal. Most people sign, oblivious to their existence.

America’s judges have generally been pro-arbitration, seeing it as a means to hack away at the backlog of court cases that have been straining American courts for a century. But the legal basis for arbitrations, a law passed by Congress in 1925, is predicated on “merchants” choosing arbitration as an alternative to a trial in court. The disputing parties were meant to be on equal footing and choose arbitration. Are people really choosing arbitration when they unknowingly agree to it before any dispute arises? Can the process remain equal when the two parties are individuals facing their employers or major corporations?

With people agreeing comprehensively to arbitration, and waiving their right to a government trial, whole chunks of the justice system are being outsourced. But does outsourced justice still look out for the little guy?

Overburdened Courts

A backlog of pending court cases is America’s quiet emergency. Defendants in criminal cases can spend years in prison before their court case even begins. The delays – poor neighborhoods in New York City regularly experience 3 year waits – have made the phrase “Justice delayed is justice denied” a common refrain. In legal speeches and papers, questioning whether the delays are so long that many American courts violate the Sixth Amendment’s right to a speedy trial seems a tired question.

For civil cases, the backlog is equally dire. Trials commonly take two to three years to resolve. Although courts hold that cases should be resolved in less than six months, the Federal district courts had over 18,000 cases pending over 6 months this past year. Post-verdict motions can keep trials alive long after a ruling is reached. Fifteen percent of civil cases in state courts, for example, are appealed, adding an average of 503 days to the trial. Retrials have long been recognized as a scourge, cited as occurring in over ⅓ of cases, although our investigation failed to turn up good public data on their frequency today.

Stephen Zach, the former president of the American Bar Association, has described these backlogs as an injustice rivaling those “perpetrated by the secret service in Cuba, the country he fled as a teenager.”

If the issue doesn’t receive the attention you would expect from Zach’s rhetoric, it’s likely because systemic delays have been a crisis for so long in the United States that people have become numb. The problem of delayed courts dates back over a century. In 1906, Roscoe Pound warned his fellow lawyers and judges at the annual American Bar Association convention that:

“Uncertainty, delay and expense, and above all the injustice of deciding cases upon points of practice, which are the mere etiquette of justice, direct results of the organization of our courts and the backwardness of our procedure, have created a deep-seated desire to keep out of court, right or wrong, on the part of every sensible businessman in the community.”

He diagnosed the problem to three aspects of the American legal system. First, he denounced the “sporting theory of justice” which dominated legal culture and resulted in lawyers launching and prolonging cases for the sake of competing and judges playing the roles of referees of the rules of the game rather than seeking the substance of the case.

America follows common law, a legal system used in a minority of the world’s countries that looks to precedent and past interpretations of laws as a guide. Pound noted that endless debates during trials over the way laws had previously been interpreted, as well as their clash with modern legislation, created confusion and prolonged trials.

Common law systems are in red. Civil law systems in blue. Source: Wikipedia

Finally, Pound believed that the legal system had poor administration. Faced with the massive management problem of resolving thousands and thousands of cases every year, America’s courtrooms were doing so inefficiently. Cases hanging in limbo between courts with overlapping jurisdictions, poor distribution of cases between busy courts and those with open dockets, and poor transfer of records between courts are all problems that led to delay.

Pound expressed confidence that reform efforts could return American courts to “swift and certain agents of justice.” But in 1958, Chief Justice of the Supreme Court Earl Warren saw the same problem:

“I must report that interminable and unjustifiable delays in our courts are today compromising the basic legal rights of countless thousands of Americans and, imperceptibly, corroding the very foundation of constitutional government in the United States.”

Like Pound, he cited the American legal culture’s love of litigation as a culprit. He also blamed America’s population boom and the intricacy of the post war economy. As with any major institution, reformers of different times and persuasions diagnosed the roots of the problem and means for its resolution differently. But from Pound to Warren to Zach, everyone agreed. The slow pace of the courts threatened Americans right to a speedy resolution of legal disputes, or to any fair trial at all.

The Arbitration Panacea

“We’ve got to move a large volume of the private cases out of the court and put them into arbitration,” Chief Justice Warren Burger told a supportive crowd at the 1985 American Arbitration Association.

Unlike criminal cases, civil cases happen only when someone in a dispute decides to go to court. Apple, for example, could have asked Samsung to enter arbitration over its use of Apple’s patented rounded corner design instead of suing them in court.

Arbitration is not that different from a court case. The two sides agree on an arbitrator, usually someone with industry and/or legal experience, who acts as a judge. Lawyers help each side through initial hearings, the exchange of information relevant to the case (mirroring the legal right to have equal access to information relevant to the case), and presenting evidence and questioning witnesses. Finally, the arbitrator decides whether to award damages or mandate certain actions to make things right.

Arbitration can end with a non-binding recommendation – a more formal version of asking a friend to weigh in. However, the two parties usually agree to be bound by the decision, which will be enforceable by law, or sign contracts when they begin working together that all disputes will be settled by binding arbitration.

Private arbitration firms provide arbitrators and manage the process. Under the American Arbitration Association, for example, filing a case can cost from several hundred dollars for a small case to $10k to $60k for a case involving multimillion dollar compensations. Companies pay several thousand dollars per day-long arbitration session. With these high fees, arbitration firms claims to be a cheaper alternative to a court case rest on reducing lawyer fees. Although they may require less hearings and formal motions for lawyers to file than in court cases, complex arbitrations can take up to a year and require hundreds of thousands in attorney fees.

While judges want to reduce the legal system’s backlog, arbitration has benefits for companies and individuals. It promises a way to skip the legal backlog and inject the private sector’s efficiency into the verdict finding process. The procedure can be kept confidential – useful for not revealing business information. And arbitrators generally have much more industry expertise than a judge or jury.

Arbitration as an alternative to the courts dates back to disputes between merchants in Ancient Athens. Its use has waxed and waned through history. In America, arbitration was popular in the late 18th century among merchants for the reason that an expert could judge cases, but declined in popularity in the 1800s due to court hostility and the difficulty of enforcing decisions. In 1925, Congress passed the Federal Arbitration Act, which allowed the results of arbitrations to be enforced by state and federal courts. Arbitration became more feasible and popular, but legal courts remained the default through the time of Justice Burger’s comments in 1985.

Burger was not a lone voice. Interest in arbitration as a resolution to overflowing dockets filled legal conferences. Judicial reforms facilitating arbitration began to be put in place, including, in the late seventies, pilot programs in which local courts forced most cases to arbitration, although they maintained a supervisory role.

A centralized effort to spread the use of arbitration followed, backed up by court decisions. In a 1984 Supreme Court case, the justices ruled that in passing the Federal Arbitration Act, “Congress declared a national policy favoring arbitration” and that state legislation could not therefore regulate arbitration’s use. The ruling was then and is still now controversial. The dissent wrote that Congress intended only to legislate the use of arbitration as an alternative to federal courts; the majority argued that “Since the overwhelming proportion of civil litigation in this country is in the state courts, Congress could not have intended to limit the Arbitration Act to disputes subject only to federal-court jurisdiction.”

A number of other rulings cemented arbitrations favored status. Another case stressed:

“The Arbitration Act establishes that, as a matter of federal law, any doubts concerning the scope of arbitrable issues should be resolved in favor of arbitration, whether the problem at hand is the construction of the contract language itself or an allegation of waiver, delay, or a like to arbitrability.”

Between lobbying, court cases, and compulsory arbitration policies, judges and lawyers successfully pushed arbitration into the mainstream as a way to reduce their backlog of civil cases.

The Vanishing Jury Trial

“The civil jury trial is fast disappearing from our legal landscape, and one important reason for its disappearance is the rapid growth of mandatory arbitration.”

~Report of the 2003 Forum for State Appellate Court Judges

Despite the ever increasing number of civil suits filed, the idea of a trial reaching its conclusion with a decision by a jury has become almost quaint. A major reason for the demise of jury decisions is that parties frequently reach settlements outside of court, either before or during the trial. But another major reason is the widespread use of arbitration.

Many of the cases going to arbitration are between companies. However, many are consumer or labor cases. Although the Federal Arbitration Act passed as a means for “merchants of equal bargaining power to agree to arbitration after a dispute arose,” arbitration clauses are buried in an incredible number of employment, banking, and other contracts. By signing these contracts, consumers and employees agree to use arbitration – and not a court case – should a conflict arise. Appeals, or appearing before a court for any reason, is not permissible.

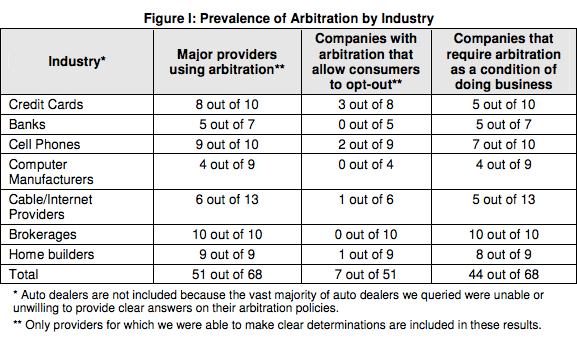

The use of these clauses, called mandatory binding arbitration by their critics, is widespread. Watchdog group Public Citizen found that roughly 75% of companies in industries like banking and home building use them in all their contracts. It is generally acknowledged that almost every car dealership has mandatory binding arbitration clauses. In the workforce, such clauses are in an estimated 20% of nonunion contracts.

Source: Public Citizen survey on the prevalence of arbitration clauses in consumer contracts

If you’re surprised to hear this, you’re not alone. Seventy nine percent of consumers believe that they can bring a lawsuit if they have a complaint with a company and 64% have never noticed or seen the arbitration clause. Yet Americans sign contracts every day that waive their 7th Amendment right to a trial.

Judging the Outsourced Legal System

If its critics are right, then binding mandatory arbitration is the least publicized death of a constitutional right in the history of the United States.

The critics of binding mandatory arbitration range from consumer and employee rights groups to respected judges and lawyers, with a steady stream of criticism being printed in legal journals every year. Their basic argument is simple. The intent of arbitration is for parties to choose it as an alternative to a court case. But when arbitration clauses are buried in the fine print of contracts, consumers make the choice unknowingly before any dispute even arises. This violates the 7th Amendment right to a trial.

The counter argument is that signing a contract is agreement, even if people sign contracts without paying attention to their contents. But the stakes are high. Cases challenging arbitration have consistently failed. A 1992 California court, for example, ruled that almost no arbitration outcome can be appealed in court, even if the outcome contradicts the law and causes an unjust outcome.

It’s also worth asking at what point the choice of arbitration becomes coerced. If you do not want to sign an arbitration clause, you simply cannot buy a used car from a dealership. Other situations have even less real choice to them. Mother Jones, for example, covered the story of the Baptist Health System’s Princeton Medical Center in Birmingham, Alabama. One day, all the low level workers were gathered for a meeting about a new arbitration process:

“Nurses, housekeepers, and lab techs crammed into a conference room where hospital administrators presented a form and told them to sign. Signing meant agreeing to submit any future employment-related complaints to an arbitrator hired by the hospital and waiving the right to sue in court. Refusing to sign meant they’d be fired.”

In situations like these, is arbitration really a choice?

One-Sided Profit Motives

Two parties with equal power and knowledge can choose a knowledgeable arbitrator that will be cost-effective and fair to both sides. But when it comes to businesses taking on consumers or employees, the asymmetry between the two sides can allow businesses and large organizations to stack the deck.

Contracts usually specify an arbitration firm to handle any disputes. So even if both sides need to agree on an arbitrator, businesses are the repeat customers. This is not lost on the judges, lawyers, and other individuals who work as arbitrators. “You would have to be unconscious not to be aware that if you rule a certain way, you can compromise your future business,” Richard Hodge, a judge turned arbitrator noted. Arbitrators regularly charge $400 an hour. Lucrative arbitration can bring in $10,000 in a day and $1 million in a year.

The incentives to rule against consumers and employees is strong. And as very little public information on arbitration decisions exist due to confidentiality, consumers have no way of knowing who is a fair arbitrator. A report by the Christian Science Monitor, whose results are mirrored elsewhere, discovered that arbitrators who ruled in favor of businesses receive the most work:

“A Monitor analysis of the last year of available data from the [National Arbitration Forum] found that arbitrators awarded in favor of creditors and debt buyers in more than 96 percent of the cases. Such results may be similar to outcomes in court. It also found that the 10 most frequently used arbitrators – who decided almost 60 percent of the cases heard – decided in favor of the consumer only 1.6 percent of the time, while arbitrators who decided three or fewer cases decided for the consumer 38 percent of the time.”

There are also many anecdotal reports of arbitrators who rule in favor of consumers never again receiving more work as an arbitrator.

This can affect cases in courtrooms, as judges know to tailor their findings to appeal to businesses so that they can retire to lucrative arbitration gigs. Judges have been known to seek coaching on how to tailor their resumes and refuse to switch from civil to criminal law as it will impact their future arbitration earnings. In fact, the judge who ruled on the aforementioned 1992 case that arbitration decisions that contradict laws are not subject to court review currently makes $6,500 a day as an arbitrator.

Another cited grievance is the lack of legal rights such as discovery. Under discovery, the parties in a legal case must share all information that could impact a verdict. In an arbitration, however, a John Doe trying to prove that his bank defrauded him has no guaranteed right to the bank’s documents. Exchanging information is generally part of the process, but since appeal is not an option, individuals have no recourse is key evidence is withheld.

Arbitration’s ban on class action lawsuits is also a concern to public interest groups. Class action lawsuits are often associated with lawyers filing frivolous lawsuits that pay out a pittance to the harmed “clients” but earn a fortune in legal fees. But they serve a valuable purpose in holding companies responsible in cases where the harm to each individual is too low to merit legal action. So while arbitration clauses unburden companies from fears of absurd lawsuits, they also unburden banks charging every customer a couple hundred dollars in extra fees from worrying that they’ll be held responsible.

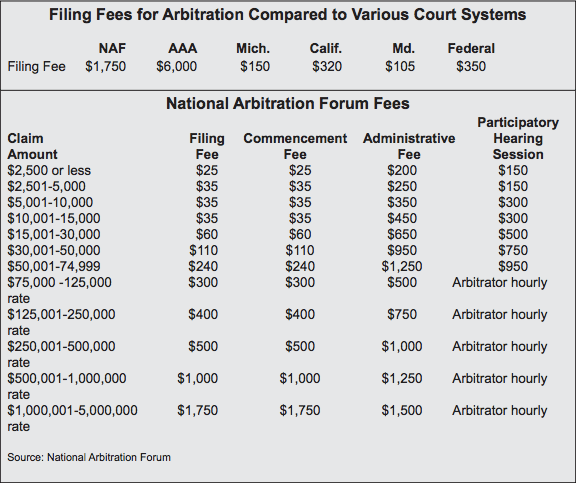

A private market should be incentivized to reduce costs to appeal to customers. But arbitrations track record at reducing legal costs in inconclusive. In the case of arbitration with consumers, that can be a boon for business. In a courtroom, the main cost is a lawyer’s time. In consumer cases, a lawyer may choose to only be paid when damages are awarded at the end of a case. In contrast, arbitration’s costs come from fees to the arbitration firm for filing cases and holding hearings. Since those costs can’t be deferred, the high costs can help businesses by disincentivizing individuals from pursuing arbitration at all.

NAF and AAA are both private arbitration firms.

Since firms keep arbitrations completely confidential, it is difficult to make data driven conclusions on whether the objections of critics are a systemic reality. But business’s arbitration practices amongst themselves is revealing. An empirical study of contracts filed with the Securities and Exchange Commission found that arbitration clauses were present in only 11% of contracts between businesses. In another example, car dealerships, which put arbitration clauses into all of their customers’ contracts, successfully lobbied Congress in 2000 to ban car makers from including mandatory arbitration clauses as it would “unilaterally deny small business automobile and truck dealers rights under state laws that are designed to bring equity to the relationship between manufacturers and dealers.”

A common practice of arbitrating consumer credit card debt represents the faustian bargain courts may have made by pushing arbitrations. The system is incredibly efficient. Companies send records of the debt consumers owe to retired judges working for an arbitration firm. Forms with the ruling desired by the credit card companies are sent to arbitrators already filled out, so the arbitrator merely needs to look over the case and sign.

It’s efficient. Arbitrators handle dozens of cases in a day. But a number of credit card companies refer to their arbitration firm as a division of their company, and the problems discussed above are particularly rampant. It seems like efficiency on the credit card companies’ terms.

Lawsuit Abuse: Fact or Fiction?

Who knew spilling coffee on yourself could make you rich? In 1994, a woman named Stella Liebeck spilled a hot cup of McDonald’s coffee on herself while riding in a car. She sued, and a jury awarded her $3 million in damages.

This account has become a poster child for the epidemic of frivolous lawsuits in America, cited when people bemoan opportunistic lawyers teaming up with greedy consumers to walk the road of an overly-litigious legal system to riches. However, the full account is much more reasonable:

“Trial testimony showed that at 180 to 190 degrees, McDonald’s coffee was much hotter than that served by other restaurants or by people in their homes. The fast-food chain had received at least 700 complaints about hot coffee in the previous decade and had paid more than half a million dollars in settlements, according to trial testimony cited by the Wall Street Journal.

“Liebeck’s injuries were hardly minor. She suffered third-degree burns on her thighs and groin area, was hospitalized for a week and had to undergo painful skin grafts. Before filing a lawsuit, she wrote McDonald’s requesting that it lower the temperature of its coffee and cover her uninsured medical bills and incidental costs of about $20,000. McDonald’s offered $800.”

Looking through the lens of “big business” versus the people is not necessarily productive. But given that pushback against Congressional attempts to ban arbitration clauses in consumer contracts have come from business groups and arbitration firms complaining of lawsuit abuse like the case above, it’s worth investigating businesses’ claims of being victims of over-litigiousness by consumers and employees.

Americans do take advantage of the legal system’s excess to launch lawsuits. New York City, for example, faces 1,500 lawsuits in Federal court (and more in local courts) that they typically settle before trial. A case from someone who claims they were mistreated when arrested may settle for ten thousand dollars. Lawyers know that the city generally settles rather than face the costs of court. But when the city decided this year to fight more lawsuits to send a message to lawyers and their clients that the city was no longer good for an easy payday, cases like the one described above ended with the city paying as little as $600 or no money in damages.

But many of the frequently cited cases of spurious lawsuits that earn jackpot payouts from juries are exaggerations or outright fabrications, the result of PR campaigns with large legal liabilities and the politicians that court their campaign contributions.

The common perception of businesses facing an explosion of lawsuits that extract absurd punitive damages appears to be at very least overblown. Rather than exploding, the number of tort (injury) cases decreased 25% from 1999 to 2008 and fell 9% in the nineties. Only 5% of civil cases result in punitive damages for an average $50,000 to $60,000, not millions.

The legal system is hurting American businesses. Drawn out lawsuits occupy company time and require that money that could be used productively be held for years in case of defeat. As the US Chamber of Commerce points out, American businesses’ liability insurance is highest in the world. But the singling out of greedy consumers and their lawyers is a red herring. It plays a role in high legal costs and uncertainty, but only a part. During the period in which tort cases decreased by a quarter, contract disputes (mostly between businesses) rose 63%, suggesting over-litigious businesses are as rampant as consumers.

For businesses dealing with high legal uncertainty and costs, it is easy to take action on lawsuits from employees and consumers through mandatory arbitration. But America’s long court cases, overflowing dockets, and inefficient processes remain, as they have for decades, a problem inherent to the wider legal system, without a single culprit or panacea.

A Wider Problem

Arbitration was intended to be a choice made by two equal parties, originally between businesses or merchants, to avoid a court case. The playing field was level and the potential for a better outcome than litigation clear. But in the rush to implement arbitration as a means to cut down on the burden of America’s overloaded courts, judicial reformers facilitated a system in which companies foist arbitration on individuals who can be pushed into a very unequal process where the incentives have skewed arbitrators against them.

Overburdened courts and unnecessary litigation are a problem. But arbitration has not solved them and solid evidence suggests that arbitration is all too often denying consumers and employees a fair outcome and legal rights.

Judicial reformers have recognized the problem of burdensome legal costs and delays since Roscoe Pound did in 1906. And they have been debating different solutions just as long: moving legal culture away from the “sporting theory of justice,” updating laws so that lawyers spend less time debating interpretations of several hundred year old legislation, and spreading best practices of judicial administration. Today, in the wake of cuts to courtrooms’ budgets during the recession, many judges are calling for increased funding.

Part of any reform effort is trying potential solutions and tracking their impact. As long as the use of arbitration in lawsuits between businesses seems to hold promise, it should be used and its value studied. Arbitration clauses in consumer and employee contracts, however, clearly have a potential to create unfair outcomes. Either judicial reformers or Congress need to address these abuses, or, if they can’t be fixed, make a final ruling on arbitration clauses and ban them outright.

This post was written by Alex Mayyasi. Follow him on Twitter here or Google Plus. .