On May 27, 1959, a mysterious, bespectacled man in a suit appeared on The Today Show. After briskly introducing himself, he turned to the camera and told America of his mission: to “clothe naked animals for the sake of decency.”

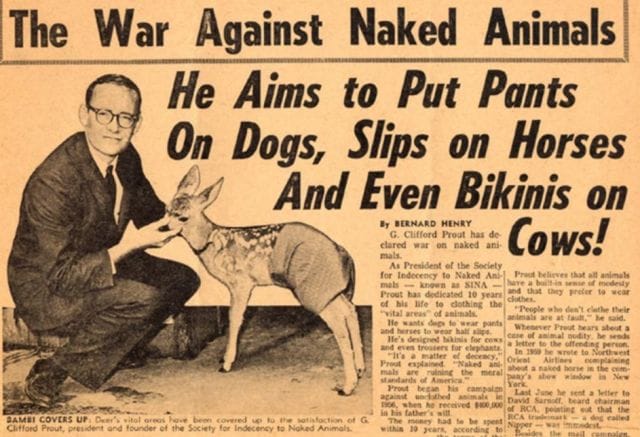

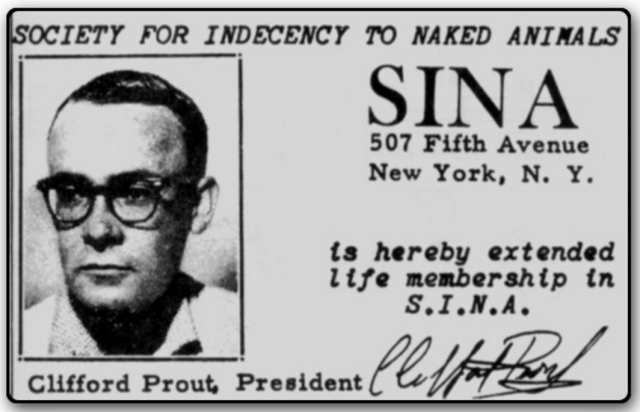

The man went by the name of G. Clifford Prout, and he claimed to be the president of an organization called The Society for Indecency to Naked Animals (S.I.N.A.). Naked animals, he harped, were “destroying the moral integrity of our great nation” — and the only solution was to cover them up with pants and dresses.

Prout’s impassioned speech did not fall on deaf ears: within days, S.I.N.A. attracted more than 50,000 members. For the next four years, the organization and its leader topped news headlines, made the rounds on talk shows, and spurred heated debates among pundits.

But S.I.N.A. was not real: it was the invention of Alan Abel, history’s greatest media hoaxster.

Over his 60-year “career” as a professional hoaxster, Abel orchestrated more than 30 high-profile stunts — from faking his own death to convincing the press he had the world’s smallest penis. He tricked top New York Times reporters, trolled Walter Cronkite, and weaseled his way into tens of thousands of print publications and talk shows.

His hoaxes attempted to make some kind of political commentary — on censorship, backwards moral standards, or the vapidity of daytime television. But often, they would be taken literally, riling up supporters and revealing ugly truths about America. He preyed on the media’s hunger for juicy stories, and ultimately revealed its gullibility.

The Funny Man

Via Alan Abel

Alan Abel came of age on the streets of Coshocton, Ohio, in the 1930s.

It was a “brutally small” town — a place largely cut off from the sweeping industrial and cultural shifts in America. “The Amish would put logs on the railroad tracks to keep trains from coming through,” says Abel. “And when there was a murder one time, the sheriff said, ‘She ain’t from around here; her nails are painted, so she must be a big city girl.’”

As a young child, Abel worked in his father’s general store. When customers ordered fabrics, he’d cut “zig-zag” and waste the material, and when he was reprimanded, he’d joke his way out of the situation.

Amid the dull work, Abel found respite in humor — a trait inherited from his mother. “She had a very wry sense of humor,” says Abel, “and she offended just about everybody.” Her laughter transcended even the darkest moments. He recalls:

“We went through the Great Depression and lost our home. The sheriff was out on the front lawn selling our furniture. It was a sad day…a very sad day — but all I can remember is that my mother was laughing through it all.”

In the late 1940s, Abel developed an affinity for percussion and enrolled in Ohio State’s music department. Here, in a dimly-lit auditorium, he inadvertently stumbled into the world of comedy. “I was giving a presentation to incoming freshman, and when I was leaving the stage, I accidentally walked too far and fell into the orchestra pit,” he recalls. “The audience just burst out laughing — and throughout my 20-minute lecture, whenever I’d pause, they’d erupt with laughter.”

Fortuitously, a talent agent was among the crowd — and the hullabaloo piqued his interest: He approached Abel and offered him $50 ($500 in 2016 dollars) to perform at a club the following week, despite having no routine. “I totally faked my way through it,” says Abel, “and I realized I could probably fake my way through it again!”

Partnering with the agent, Abel embarked on a fruitful journey as a performer. With his drum and joke book, he made the rounds at New York’s famous comedy clubs and even appeared on Armstrong Circle Theatre (a now-defunct NBC show) with Grace Kelly. After a spat with his agent, Abel took his career into his own hands — but in a sea of talent, he needed a gimmick to stand out.

“I realized I’d faked my way into the industry,” he says, “and that I could probably audition as somebody else just about anywhere — create a hoax — and get away with it.”

The Society for Indecency to Naked Animals

Via Alan Abel

One day, while driving in Texas, Abel encountered a traffic jam. When he peered ahead, he spotted an unusual holdup: a cow and a bull were in the middle of the road having sex. He recalls his reaction:

“I looked around at all the people gathered, and I saw different expressions: two women were hiding their heads; a man and a woman were looking the other way, like they hadn’t seen it; one woman was indignant and angry. I thought, here are all these people mortified over these two animals, which have no sense of morality, no concept of sin. The whole world is their bedroom.”

Reflecting on this scene, Abel returned home and wrote a satirical letter to The Saturday Evening Post. He proposed a fictitious organization — The Society for Indecency to Naked Animals (S.I.N.A.) — which aimed to clothe all naked animals in the name of morality. A few weeks later, he received a letter from the editor, who not only rejected the piece, but found S.I.N.A. deplorable. “He thought it was real!” says Abel. “So I thought, ‘Who else might think it’s real?’”

In the early months of 1959, Abel and his wife, Jeanne, created a backstory to S.I.N.A., to make it seem credible. Abel recruited his good friend Buck Henry (who later wrote the screenplay for The Graduate) to be “G. Clifford Prout,” S.I.N.A.’s President, a man who’d inherited $400,000 and had decided to make clothing naked animals his life’s work. The trio studied the “rhetoric of conservative moralists,” then printed out thousands of leaflets — each adorned with an image of a horse in underwear and the slogan “A nude horse is a rude horse” — and sent them out to talk shows.

Buck Henry, as S.I.N.A. president, Clifford Prout; Via Alan Abel

The Today Show took the bait. On March 27, 1959, Henry appeared on the show and tricked Americans into believing that S.I.N.A. was real. Within weeks, an alleged 50,000 members wrote in to join the effort.

Throughout 1959 and 1960, S.I.N.A. ballooned in popularity: it made the rounds on every major talk show, news station, and radio station, and even attracted picketers at the White House, who held signs imploring President Kennedy to “cover all horses’ private parts.” The movement polarized Americans: some were outraged by it, and others passionately supported it. Few realized it was a joke — despite S.I.N.A.’s absurd theme song, “Ode to Decency.”

On August 21, 1962, S.I.N.A. made a fateful appearance on CBS News with Walter Cronkite.

As Buck Henry (as G. Clifford Prout) sang S.I.N.A.’s marching song with his ukulele to an unamused Cronkite, a CBS crewmember recognized the actor. After the show wrapped up, the employee confronted Henry, and S.I.N.A. was revealed as a hoax.

“When Cronkite eventually found out that he’d been conned, and I was the guy behind it, he called me up,” says Abel. “I’d never heard him that angry on TV — not about Hitler, Saddam Hussein, or Fidel Castro. He was furious with me.”

A few months later, Time Magazine wrote a story exposing the hoax, and Abel revealed the true message of his operation: S.I.N.A. wasn’t just a hoax — it was a commentary on the state of affairs in America.

“I had no interest in actually putting shorts on horses, or mumus on cows,” says Abel. “S.I.N.A. was a satirical riff on censorship: it mocked the moral maniacs who were banning films, books, records, and plays during that time period.”

S.I.N.A. protestors gather outside the White House; Via Alan Abel

But for every person who understood the purpose of the hoax, there was another who took it at face value: hundreds of supporters came out of the woodwork, championing S.I.N.A. for its efforts. Some even attempted to donate money. “The largest check came from a woman in Santa Barbara — she wanted to donate $40,000 to S.I.N.A.,” says Abel. “I called the bank, and it was good, but I couldn’t possibly accept it.”

This support did not wane after the hoax was revealed — and Abel realized he was on to something special.

“After I pulled that off, I felt this was something that was fun, that I could do well,” says Abel. “Laughter made me feel like a better person — and I got hooked.”

A Family Affair

Via Alan Abel

In 1960, at the height of S.I.N.A., Abel met a man on the New York subway and got to talking about his hoax. The man, a fellow by the name of Max Sackheim, turned out to be a multi-millionaire who’d made his fortune in the mail marketing business — and he loved Abel’s work.

“He told me if I ever started a project and needed money, I should ask him,” says Abel. “So from that point forward, I’d just call him up with an idea for a prank and tell him how much I needed (usually $3,000-4,000), and he’d immediately wire me $5,000.”

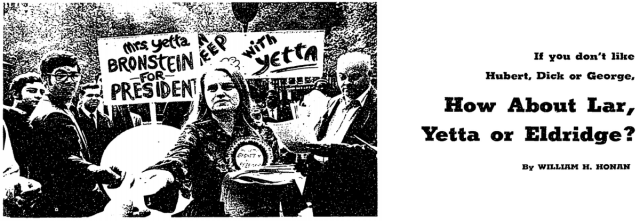

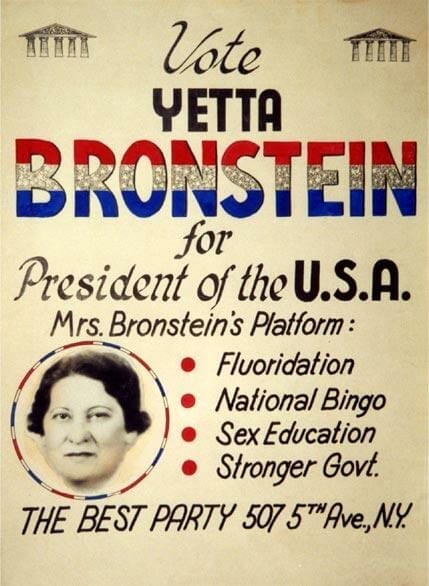

Newly minted with funding, Abel exacted his next hoax: he created a fictional presidential candidate and proceeded to convince America that she was running in the 1964 election. Her name was “Yetta Bronstein.” A 48-year-old Jewish housewife from the Bronx, she ran as part of the (totally made-up) “Best Party” with a rather unorthodox platform. Abel explains:

“She wanted to: institute a national bingo system; put a ‘truth serum’ in the Senate drinking fountains; place a suggestion box on the White House fence; take congress off salary and put them on state commission; lower all the curbs in the city of New York; use a mental detector for anyone on tour of the White House; and, lastly, put a nude photo of Brigitte Bardot on postage stamps.”

As he did with S.I.N.A., Abel printed out hundreds of “official campaign” press releases and sent them to the media. Before long, his phone began to ring with inquiries. He recruited his wife, Jeanne, to pose as the character and field phone calls from the press.

Via Alan Abel

She was convincing: within weeks, Yetta Bronstein spread like wildfire throughout the political news channels. Shockingly, she never made a public appearance — but Abel, a quick thinker, sent off a picture of his mother, and the press picked that up instead. Soon, Yetta became the motherly candidate that everyone loved.

“I figure we need a Jewish mother in the White House,” she told the New York Times (which believed her campaign to be real). “A mother will take care of things. Maybe our country could use a queen, you know? It certainly wouldn’t do any harm.”

In campaign literature, she sold her image even harder: “Why should you vote for me?” she asked. “Think of all the things your mother did for you — the feeding, changing, washing, ironing, lying for you, crying for you. Now you can pay her back by putting me in office. I will represent all your mothers and act in their behalf for you.”

Before long, Yetta Bronstein’s slogans — “Vote for Yetta and watch things get betta” and “Put a mother in the White House” — were proudly displayed on lawns across America, and she gained a cult following.

Lyndon B. Johnson went on to trounce Barry Goldwater in the 1964 election, and Yetta was revealed as a hoax by what Abel calls a “small, cruddy newspaper.” The revelation didn’t stop her from getting a few thousand write-in votes. Four years later, she ran in the 1968 election, drumming up similar support.

Unwitting citizens rally in support of fictional Presidential candidate Yetta Bronstein; Via Alan Abel

Throughout the late 1960s and early 1970s, Abel exacted dozens of smaller pranks: In 1967, inspired by the hippie movement, he created a topless string quartet; it became so popular that Frank Sinatra once offered them a record deal. (They purportedly turned it down). In 1970, under the auspices of a group called “Taxpayers Anonymous,” he sued the IRS, demanding an open examination of their books. In 1972, he covered himself in bandages and posed as Howard Hughes at a press conference, claiming he would “freeze himself through cryogenics and return when the stock market peaked.” In 1975, he was featured on national news outlets after creating a “School for Beggars,” where people were taught how to professionally panhandle (a satirical commentary on the rise of unemployment in America).

By the late 1970s, Abel had been blacklisted by a number of national new publications and television shows for his antics — a restriction he easily circumvented by hiring actors (including his own family members) to exact his stunts. In underground hoax circles, he became something of a cult superhero.

Then, just as Abel began to gain steam as a famous prankster, he died.

The Death of Alan Abel

Via Alan Abel

Alan Abel had carved out a name for himself as a professional media hoaxster. He’d not only duped the media on multiple occasions, but had segued his experiences into two books (“The Great American Hoax”, “The President I Almost Was”) and a pair of mockumentaries (“Is There Sex After Death?”, “The Faking of the President”). As he rose in fame, producers became interested in making his life story into a feature-length film.

On one occasion, in 1979, he went into Universal Pictures to discuss selling the rights to his story. Ultimately, the studio passed — and on his way out of the building, Abel overheard an unsavory conversation about himself.

“I was in the elevator with the Universal lawyers; they didn’t recognize me, and they started talking,” recalls Abel. “One lawyer said to the other, ‘Let’s just wait it out until he dies, then buy the rights for peanuts!’”

“I thought, ‘Why, that SOB! How dare he think of me as a piece of property!’” continues Abel. “And I decided I’d fake my own death and show them up.”

Abel called his friend and convinced him to install a phone in his trailer with a voice machine that claimed to be a funeral home. Next, he rented a space at a local church for his “wake and funeral service.” Then, says Abel, he died.

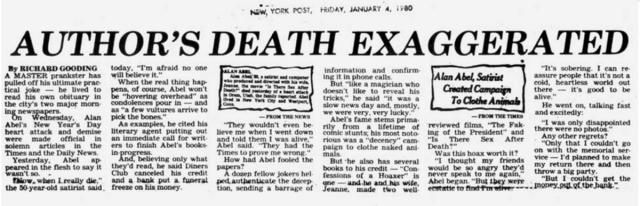

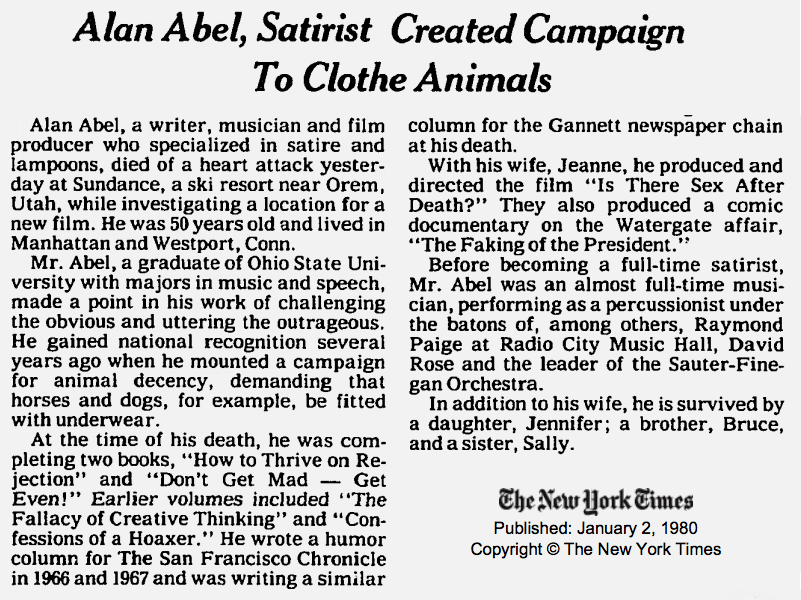

“A friend leaked to the press that I’d gone up to Robert Redford’s ski lodge in Utah, disappeared down the slope, and died,” chuckles Abel. “And somehow, that information was funneled to the New York Times.”

When the Times did its diligent fact-checking, the “funeral director” (Alan’s friend in the trailer) verified that he had the body, and the church corroborated that the space had been booked for the wake. The following morning — January 2, 1980 — the paper devoted 8 inches of space to a fawning obituary of Alan Abel:

Via The New York Times archive

Abel describes the experience of walking to the newsstand and reading his own obituary as “surreal”. But, as he would quickly find out, being dead came with its drawbacks.

“After I died, I went to the bank to get some money to pay for my wake, but I couldn’t get the money out — they’d blocked my accounts!” he laughs. What’s more, his long-lost relatives started coming out of the woodwork, pining over his assets. “One aunt I never even knew drove cross-country to put in a claim for my furniture,” says Abel. “Who needs a relative like that?”

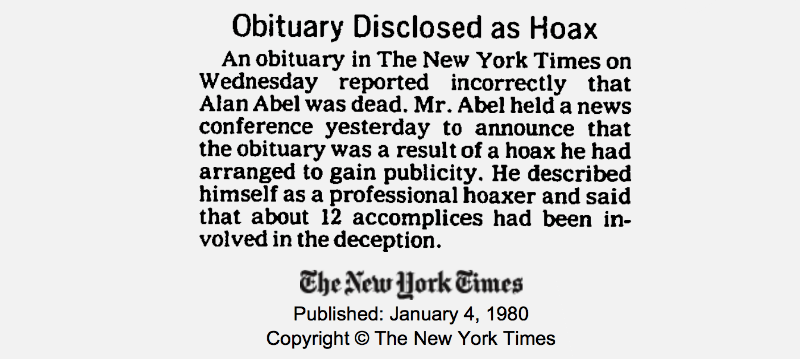

Perturbed, Abel decided he’d had his fun: the next day, he held a self-organized press conference, revealing to reporters that his demise was “gravely exaggerated.”

“Four of the obituary writers for the New York Times were in the front row,” says Abel. “They didn’t say a word the whole time — they never responded, never showed any emotion whatsoever. They were like 4 Duracell batteries on legs that had been programmed to sit and do nothing. They were ready to kill.”

Two days after the obituary was printed, the Times published an embarrassing retraction:

Via The New York Times archive

In the wake of his “rebirth,” Abel set out on a torrent of new pranks.

During the 1983 Super Bowl game, he somehow finagled a fake referee onto the field. The man made four “calls” — really just non-sensical hand gestures — before being tackled on-field by a police officer (who was also hired by Abel). The following year, he launched “Females for Felons,” an organization which sought to “provide prostitutes for men behind bars.” Posing as its founder (a delusional ex-con named Ralph Sturges), Abel made the rounds on TV talk shows, riling up audiences with his incendiary comments.

In the course of this latter prank, Abel began to develop a distaste for talk shows. “I found them vapid and totally devoid of meaningful content,” says Abel. “And that’s why I decided to prank them.”

The Talk Show Terrorizer

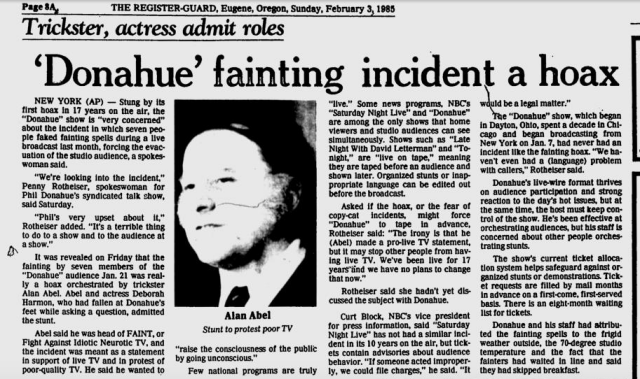

The Register-Guard (1985)

In early 1985, the Phil Donahue Show — a popular talk show at the time — moved its set from Chicago to New York City.

About 40 minutes into his first show (on the topic of gay senior citizens), Phil Donahue turned to the audience to field questions. A woman was picked out. She stood, and as Donahue held the microphone to her mouth, she said “I’m feeling a little….uh…ohhhh.” She wavered back and forth. And then, on live television, she fainted. The show immediately cut to a commercial break.

When the show returned on air, Donahue addressed the camera — “Our viewers are entitled to know that, uh…” — and then, another person fainted. Through the gasps of the crowd, Donahue could be heard shouting, “We’ve lost another one!” In rapid succession, 5 more people fainted, at which point Donahue paused the show and vacated the entire studio audience as the camera panned out over the empty room.

“We think it was the combination of the lights, the anxiety of live television, and the heat,” hypothesized Donahue later that evening. The show’s spokeswoman, Penny Rotheiser, went further, stating that those who fainted had had little or no breakfast before the 9 a.m. show…and many were wearing heavy clothing because of the subzero temperatures outside, while temperatures in the studio were in the mid-70s.”

The reality was much simpler: Abel had orchestrated the whole thing.

In the weeks prior to the showing, Abel, who thought the show “lacked any real substance or meaningful conversation,” had decided to infiltrate it: He recruited 7 actors, each of whom he paid $50. Through an “inside connection” with a casting director, he then planted them in the live studio audience for the January 21, 1985 show, giving them instructions to faint when asked a question.

“I called it ‘Fight Against Idiotic Neurotic Television,’ or F.A.I.N.T. for short,” he says. “The purpose was to call out the sensationalism — the total lack of substance — of American talk shows.”

***

In 1994, Abel struck again — this time on the Jenny Jones Show.

Through another “inside connection,” he and finagled his way onto an episode of the tabloid talk show that dealt with the topic of revenge. On air, his “wife” (played by an actress) told Jones what happened when she supposedly caught Abel with another woman:

“I waited til I was sure he was asleep, then I grabbed my trusty little tube of Krazy Glue, and pulled back the sheets,” she told an expectant Jones. “And I glued his penis to his butt, right where it belonged!”

The audience (and Jones) erupted in laughter. Some even applauded. One resident of Chicago recognized Abel’s face, and called in to report the hoax, but the network was unable to pull it in time. The segment aired in more than 30 states.

“I think we made our point pretty clearly,” says Abel. “And that’s that talk shows have no limit to how low they’ll stoop.”

It wasn’t the last time Abel’s penis would take on a starring role in one of his hoaxes.

In 1998, Abel came across a classified ad looking for men to participate in an HBO special called “Private Dicks.” The program was to feature earnest sit-down interviews with men about their penis size — something Abel says there was “no way” he could resist.

“I figured all these guys were gonna call and brag about their prowess, and their length, and width, and all that,” he says. “I decided to call in and say I was the smallest in the world — one inch, erect. They ate it up.”

After a brief interview (during which he avoided the pleas of the director to remove his pants and expose himself), Abel was cleared to be in the documentary.

He posed as “Bruce,” a 57-year-old musician from Ohio — and from a stool in a dimly-lit studio, he talked candidly of his tiny member.

“I grew up in a small town in Ohio where the penis was verboten: you never heard the word ‘cock’ or ‘prick,’” says Abel in the documentary. “My penis is about half the size of a cigar when its erect. It’s rather tiny. That’s okay, though: Just give me darkness. I’ll do okay and you will too. You’ll love it.”

After the film was made, the producers found out they’d been had.

“The people from HBO were absolutely outraged at first,” says Abel. “But they eventually realized I was the only person in the film who admitted to an astronomically tiny penis. Without me, it wouldn’t have worked.”

Satire as a Truth Serum

As Abel progressed into his 70s, his pranks grew more political and ambitious. And in Trumpian fashion, the more outrageous his stunts got, the more people people came out of the woodwork to support his opinions.

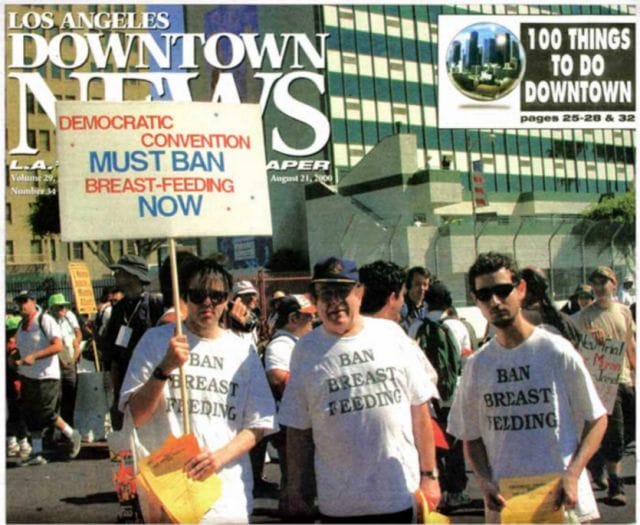

In 2000, for instance, he launched “Citizens Against Breastfeeding,” a fake watchdog group that sought to ban all public breastfeeding. Abel recruited dozens of “protesters,” then parked them outside of the Republican National Convention, where they passed out the following fliers:

The organization claimed that breastfeeding violated babies’ civil rights and fostered insestuous relationships. Abel once again posed as its founder. He appeared on news segments, where he verbally jousted with mothers and legitimate breastfeeding advocacy groups, and warned of the perils of the “naughty nipple.”

“Hundreds of people called in and left comments on the Internet, thinking it was real,” says Abel. “We had people saying, ‘Finally! A group that fights the immorality of breastfeeding!’ So really, this fake organization revealed sad truths about America’s real opinions.”

Though Abel revealed the group as a hoax, it continues to be taken seriously, and it’s often cited by misinformed bloggers or refuted in YouTube comments.

In 2006, Abel partnered with Esquire Magazine for an April Fool’s issue, where he proposed a national fat tax. “Every family should weigh in at the post office, on or before April 15, and pay $5 a pound for each member,” he told the reporter. “This aggregate amount will give Uncle Sam as much, if not more, than taxing income.”

Despite clear indications this it was a hoax, dozens of readers showed their support of the idea.

“I appreciate your story and I agree that fat people are costing us money,” wrote one reader, “but I go to the gym five times a week and I have a 32-inch waist and [based on your tax calculation], I’d owe $6,000 in fat tax.’”

Protestors earnestly supported Abel’s breastfeeding ban hoax; Via Alan Abel

By this time, Abel had become so notorious for his pranking abilities that he launched a freelance business “helping people out with revenge.” For a fee of $500, people who’d been wronged came to Abel for help planning a retaliation — something meant to “amuse and embarrass.”

He elaborates on one such instance:

“A few years ago, one young lady called, and said she’d met one of her old classmates in the ladies room. They were both wearing similar engagement rings, and, after talking, she found out they were both engaged to marry the same man! They were horrified.

The guy was a businessman — a hedge fund guy. So, I set up a fake award to give him. He arrived at this local country club, in a limo with his whole family, to receive the award. And behind the door were these two girls. He turned white! He was in total shock! They each sold their rings, made some money on that, and paid me my share.”

His benefactor long gone, Abel occasionally made money by giving lectures at college campuses and galas about his career. After a final hurrah in 2009 — a campaign against birdwatchers called “Stop Bird Porn” — Abel unofficially tipped his cap as a hoaxster.

The Beauty of Laughter

Alan Abel headshot by Denny Renshaw (modified by Priceonomics)

Today, Alan Abel is 86-years-old. He lives a quiet life on a tree-lined street in Southbury, Connecticut, with his wife, Jeanne. Out and about, he is rarely recognized — though his daughter recently made a documentary about him, and hopes to change that.

On occasion, he’ll receive fan mail — usually a young kid looking for advice on how to hoax professionally. “I tell them to go into undertaking,” jokes Abel. “People are dying all the time, and you’re always going to have business.”

“One question I get a lot is: Why do you do what you do?” says Abel, taking on a reverent tone. He pauses, clears his throat, mulls over his 50 years of infiltrating newscasts, talk shows, newspapers, magazines, and press conferences.

And then, he calls his wife over and sings a song.

For the first time during the course of a two-hour chat, he emits a deep, guttural, uninhibited laugh — a laugh that rattles through the phone’s receiver and seems to shake him to the bone.

“Laughter,” he says, “is the only tranquilizer without side effects. It’s kept me young all these years, and I believe in it dearly. It’s very reassuring to know that there are a lot of people — all ages, all sizes, all shapes — who find that common denominator between what is amusing and what isn’t.”

But as the interview draws to a close, one question remains — a very pertinent one, given who we’re talking to: Have we been had? Is the man one the other end of the line truly Alan Abel?

“I’m leveling with you,” he admits, before launching into another rhapsody with his wife. “It’s really me.”

Our next post looks at the consequences of Cordon Bleu licensing its name to expensive, scandal-ridden schools in the United States → join our email list. A version of this article was first published March 3, 2016.