“Something was very wrong. Here was this guy from nowhere, and he kept going around the board and hitting the bonus boxes every time. It was bedlam, I can tell you. And we couldn’t stop this guy.”

~ Michael Brockman, head of the CBS daytime programming department, 1984

![]()

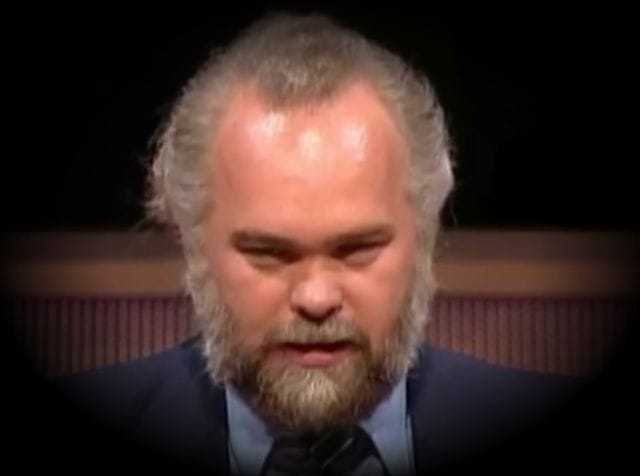

On May 19, 1984, before a live studio audience for the game show Press Your Luck, a squirrely-looking, gray-bearded 35-year-old named Michael Larson leapt from behind his podium and squealed with joy.

For the contestant, the show’s catchphrase, “Big bucks, big bucks, no Whammies!”, had just come to fruition: in an era where no single contestant ever won more than $40,000 — not even those competing on the ever-popular The Price In Right, or Wheel of Fortune — Larson had earned $110,237 ($253,000 in 2015 dollars).

And in achieving this, he’d overcome insurmountable odds…or had he?

While CBS executives in the control looked on in horror and disbelief, Larson harbored a secret: he’d cracked the code of Press Your Luck. For months, he’d studied the show’s game board, which lit up squares in a supposedly “random” sequence, and found that, in actuality, it was repeating the same 5 patterns over and over again.

What ensued was one of daytime television’s strangest moments — one that exposed the follies of both man and technology.

Press Your Luck: The Titanic of Game Shows

In September of 1983, a flashy new game show called Press Your Luck hit the daytime broadcast on CBS.

The brainchild of two veteran television producers, it was billed as the most “technologically advanced” program of its kind; utilizing cutting-edge audio-visual equipment, it tempted viewers and contestants with enticingly large payouts.

As far as rules and structure go, Press Your Luck was pretty straightforward. Each episode began with the show’s host, Peter Tomarken, asking the three contestants a series of multiple choice questions. Whoever buzzed first and answered correctly earned three “spins” on the “Big Board,” the prized centerpiece of the game show:

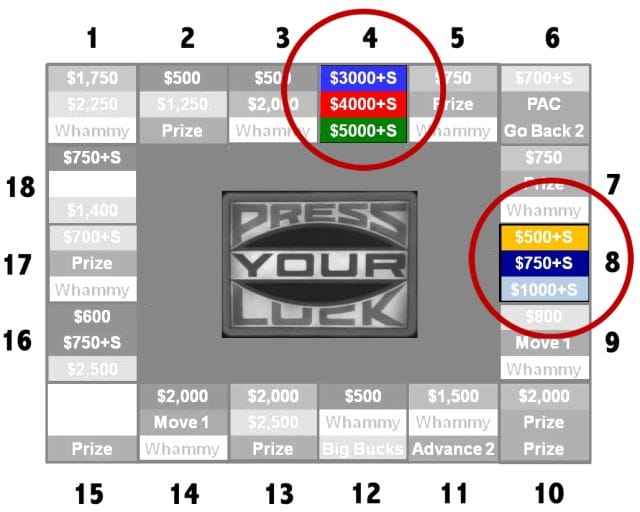

This Big Board was made up of 18 backlit squares, each containing a constant rotation of various cash and item prizes, as well as a selection called a “Whammy.” When a player’s spin began, a selector light rapidly bounced around the squares, lighting them up in a seemingly random sequence; the player would then choose when to slam down a big red button, stopping the board. Whichever square was lit up dictated the player’s fate for that spin. At the end of each spin, the player either had the option to “press his/her luck” (spin again) or pass any remaining spins to the next player.

The board contained a wide array of outcomes: cash amounts ranging from $500-$,5000, vacation packages, material prizes (boats, appliances, etc.), “Pick a Corner” (in which the contestant would select any corner square on the board), various instructions (“Go Back 2,” “Move 1”), and finally, the Whammy. If a player landed on this dreaded tile, an annoying animated gremlin in a red suit would come out and reap the player of every cent he/she had amassed.

Many of the cash prize squares on the board also contained an extra spin (+S). Hypothetically, this made it possible for a player to continue on indefinitely, assuming he/she consistently landed on the cash+spin squares — though the show had made certain that the odds of this occurring were nearly impossible.

Of the Big Board’s 54 outcomes (18 squares with 3 rotating options each), 9 were a “Whammy.” That meant that, on any given spin, a player had 1 in 6 odds of losing everything. What’s more, the team that had programmed the board was confident that both the speed and “random” nature of its sequences would prevent contestants from winning more than $25,000. Over the first few episodes, the average winnings hovered around $14,000.

In the words of former CBS executive Ron Schwab, Press Your Luck was “like the Titanic — it was the technological marvel of its time.” Unfortunately for CBS, and iceberg loomed, and its name was Michael Larson.

The Game Show Hustler

Michael Larson was never interested in following the rules.

The youngest of four boys, he was born in 1949, somewhere between Cincinnati and Dayton, Ohio. By middle school, he’d established a lucrative enterprise smuggling candy bars into his gym class and selling them at a considerable mark-up. While tenacious and intelligent, he was always looking for a quick, easy way to get rich.

“He didn’t understand the value of good, hard, honest work,” his older brother, James, later bemoaned. “He thought those people were fools.”

Instead, Larson invested great amounts of time seeking out loopholes and taking advantage of them, often illegally. In one instance, he found a bank that gave out $500 for starting a new checking fund; using fake names, he opened dozens of accounts, waited the minimum necessary duration, then withdrew the money. On another occasion, he registered a business under a family member’s name, hired himself as an employee, then fired himself to collect unemployment benefits.

Throughout his 20s and 30s, Larson only intermittently found real work — first as an air conditioner mechanic, and later, an ice cream truck driver — all the while graduating to more intensive ploys. He began to spend every waking minute in front of a television, watching infomercials and game shows, in hopes of identifying some kind of opportunity to get rich quick.

“He had an entire wall of 25-inch televisions stacked one on top of the other,” recalled his then-girlfriend, Teresa Dinwitty. “He watched them all at once, and it got so hot, the paint peeled off the wall.”

After determining that more popular daytime game shows like The Price Is Right and Wheel of Fortune were un-hackable, Larson began to focus on a relative newcomer: Press Your Luck.

Using his VCR, he recorded episodes; for 18 hours a day, he sat perched in front of the screens, analyzing every spin of the Big Board frame-by-frame, looking for patterns.

Then, incredibly, he found one.

After six months of scrupulous examination, Larson realized that the “random” sequences on Press Your Luck’s Big Board weren’t random at all, but rather five looping patterns that would always jump between the same squares. He wrote down these patterns, memorized them, then honed his timing by watching re-runs and hitting “pause” on his VCR remote when he suspected the board would land on a given square.

Most crucially, Larson determined that two squares on the game board, #4 and #8, always contained a combination of cash and an extra spin. Since he’d memorized the patterns, he knew exactly when the board would land on each square:

Larson analyzed the board and found that each of its 18 squares contained three rotating options (54 total); then, he found that squares 4 and 8 always offered a cash prize with an extra spin (and never contained a dreaded Whammy):

Larson was ecstatic. He’d uncovered a flaw in the game, perfected his technique, and, in his opinion, possessed the ability to amass a fortune. There was just one thing left to do: he had to finagle his way onto the show.

Armed with little more than the address of CBS Television City, Larson spend the last of his ailing funds on a bus ticket from Ohio to Los Angeles, with the intention of auditioning for Press Your Luck.

Bobby Edwards, the show’s contestant supervisor, remembers feeling uneasy when Larson strutted into the audition room:

“We held daily auditions: one in the morning, and one in the afternoon, maybe 50 people in each session. [Larson] walked up right off the street, and told us he was an ice cream man from Ohio…There was something about him that I just didn’t believe. I didn’t trust him.”

Despite Edwards’ doubts, Larson, an ever-enterprising schmoozer, managed to convince Bill Carruthers, the show’s executive producer, that he was a small-town plebeian desperately in need of a chance to win some money. Always in search of a good sob story, the network agreed: Larson was slotted to appear on the fifth taping of the day, May 19, 1984.

Michael Larson Presses His Luck

On the day of filming, Larson arrived early. Dressed in a cheap suit jacket and a shirt he’d bought for 65 cents at a thrift store, he exuded the intense confidence of a man preparing to go into battle. His competitors, Ed Long (a Baptist minister) and Janie Litras (a dental assistant), were completely oblivious to their impending doom.

When the show’s host, Peter Tomarken, asked Larson what he did for a living, his response was self-assured: “I drive an ice cream truck in the summer and I hope to win enough money today not to have to do that.”

Larson got off to a rocky start. On the very first question (“You’ve probably got President Franklin D. Roosevelt in your pocket or purse right now, because his likeness is on the head side”), he buzzed prematurely and yelled, “$50 bill!” (the correct answer was, of course “a dime”). For the remainder of the question round, he sat silently, with a perplexed look on his face. Eventually, he finished with 3 spins, putting him in last place behind Long’s 4 and Litras’ 10.

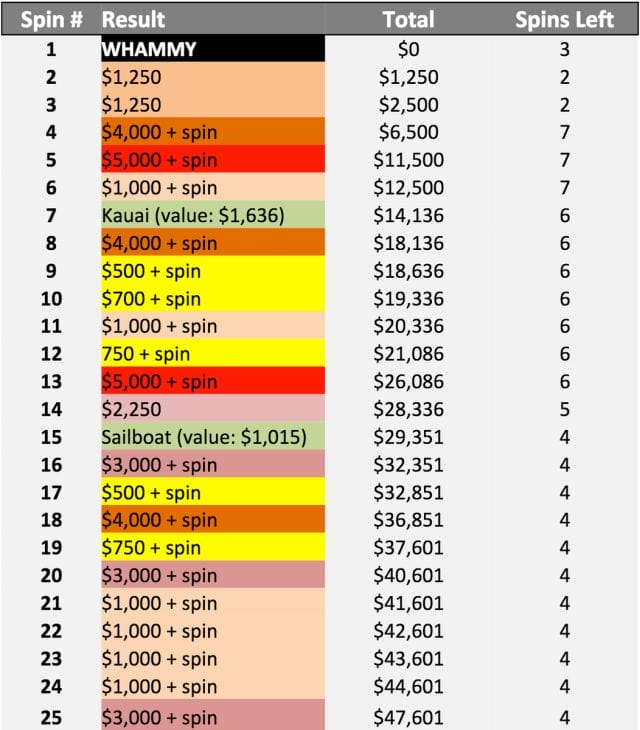

Since he’d come in last, the rules dictated that Larson spin first. This did not go well: on his very first spin of the board, he hit a Whammy. However, he quickly recovered: hovering his hands just above the buzzer, he intently watched the light travel around the board, and, recognizing the patterns, hit square #4 ($1,250) on his second and third spins.

Still, at the end of round one, Larson sat in last place, with $2,500:

In round two, Larson came to life.

During the second question round, he managed to correctly answer three questions, bumping his total spins up to 7; since he sat in last place, he again spun first.

With his first two spins, he landed on square #4, earning him $4,000, and $5,000. Then, over 10 ensuing spins, he proceeded to rack up $29,351 in winnings without hitting a Whammy. The audience roared with excitement, yet Larson seemed unsure of himself. While he was aiming to hit squares #4 and #8, he missed his mark four times during this period of play, unintentionally landing on #7 (a trip to Kauai), #17 ($700 + a spin), #6 ($2,250), and #7 again (this time, a sailboat).

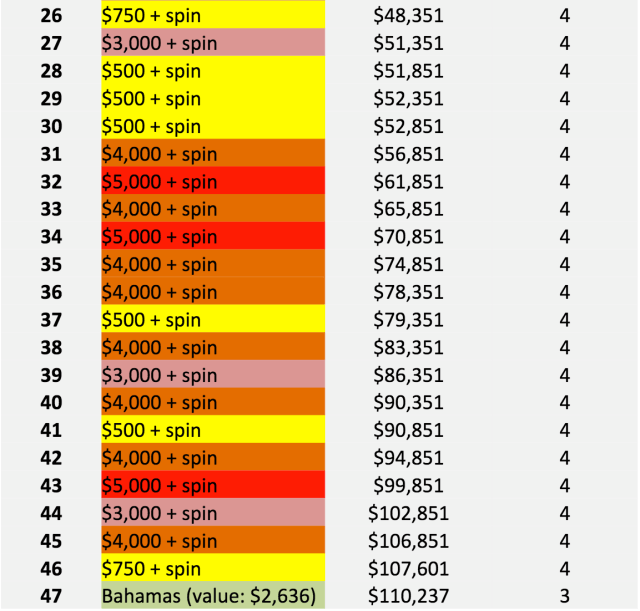

After the sailboat, with 4 spins remaining, he locked into what industry execs have since deemed to be one of the “most absurd grooves” in game show history. Over the course of 31 consecutive spins, he persistently nailed squares #4 and #8; astonishingly, 20 of them were $1,000 or higher:

Priceonomics; compiled from archived footage

During Larson’s rally, Tomarken, the show’s host, grew increasingly nervous. His quips graduated from shock (“We’ve never seen this happen! You’re on a roll!”) to disbelief (“This is unreal”), to utter disgust (“You’ve got to be kidding me”) — and once Larson hit the $30,000 mark, he started pressuring the contestant to bow out.

“Michael, you really are PRESSING YOUR LUCK,” he warned at one point, wagging a finger in the air. “After this show, you’re going to get a special call from the president of CBS…”

Finally, 40 successful spins and $102,851 later, Larson passed his final 3 spins to Ed Long, fearing that he was beginning to lose focus. On his very first spin, Long hit a Whammy and lost all of his cash. When the spins were passed to Litras, she too hit a Whammy on her first try. In the hopes that Larson would screw up and lose his cash, she then passed the spins back to him, but Larson did not falter. Instead, he landed $4,750 and a trip to the Bahamas.

When the game ended, Larson raised his arms in triumph and emitted a primal scream: he had secured $104,950 in cash, a sailboat ($1,015), and two all-inclusive trips, which brought his total winnings to $110,237. Ed Long distantly trailed in second place with $11,516 (which he’d earned in a prior episode as a returning champion), and Janie Litras left with $0.

Larson had made a fool of CBS: He’d spun the show’s board 47 times. He’d won more than any other daytime game show contestant in history. And he’d done so by finding an inherent flaw in television’s most “technologically impressive” game board.

***

While Larson celebrated on stage, the powers that be at CBS sat dumbfounded and deflated.

“I wasn’t there that day, but boy did I hear about it,” Bob Boden, a former executive at CBS Daytime Programming, later told TVLand. “It went through the hallways of CBS like a rocket.”

Darlene Lieblich Tipton was in the Press Your Luck control room that day. As a CBS employee, it was her job to ensure that contestants were playing by the rules. In an interview with This American Life, she recalled the mounting tension backstage:

“It wasn’t unusual for contestants to go on streaks. It was kind of the way the game was designed. But after about 10 spins of the board, it started to become obvious that he was hitting same prize in same square every time. And that’s skill — it’s not random, and it’s not luck. He could aim and hit, which we didn’t think was possible. First, the booth got very quiet, then there was an, ‘OH MY GOD, OH MY GOD, OH MY GOD, what do we do?!’ People were turning to me saying, ‘Can we stop this?’”

Statistically, it was extremely unlikely that Larson had simply gotten lucky. Given the 1 in 6 odds of hitting a “Whammy,” the probability of going 45 spins in a row without hitting one was (5/6)^45, or .027%. Larson had beat odds of roughly 3 out of 10,000.

Despite this, Tipton saw nothing illegal in Larson’s play: he wasn’t visibly breaking any rules, and she could do nothing but helplessly stand by and watch him dominate the show.

The following day, CBS launched a full out investigation. Nearly every department head at the network gathered in a musty room and reviewed the tape frame-by-frame — just as Larson had done on his VCR with Press Your Luck episodes. However, even after this review, they could find no faults in his method. “He fit every criteria,” one executive told GSN. “He had not broken any rules of the game, he had played fairly, and he was an eligible contestant. We paid him his money…he was simply smarter than CBS.”

After Larson’s win, the “Big Board” was re-programmed: its 5 “random” patterns were expanded to 32, and the control panel was replaced by a PC running a far superior randomizer. Larson’s streak had gone on so long that CBS had to split the airing into two half-hour segments; the network was so thoroughly embarrassed by the board’s flaw that they only aired the episodes once.

In September of 1986, just two years after Larson’s Press Your Luck appearance, the show was cancelled.

The Champion’s Downfall

Newly minted with around $90,000 in post-tax earnings, Larson initially indicated that he was ready to turn his life around and be more responsible. “I tried to get him to look at some reasonable investments,” his brother, James, told a reporter. “He put it in the bank…and for some time, was doing the right thing.”

But a few months later, while listening to the radio, Larson heard about a contest he just couldn’t resist: the show read a serial number on air every day, and if a listener could match that number to a $1 bill, he would win $30,000.

Larson visited five different banks, withdrawing nearly $50,000 in $1 bills. Then, over the course of two weeks, he analyzed every bill in hopes of winning. A match never came, and Larson, who’d grown lazy by then, resolved to just leave the bills in his home. This didn’t work out too well: one night, he left to Christmas party and came home to a kicked-in back door. All the money was gone.

This was the beginning of Larson’s downward spiral. Teresa Dinwitty, then Larson’s common-law wife, recalls then that aggression mounted to such a level that she feared for her life. She fled with her children and demanded Larson leave her house.

Eventually, Larson moved to Dayton, Ohio, where he assumed a role as an assistant manager at Walmart, but this didn’t last long. He grew disillusioned with his minimal pay and, after meeting another woman, launched his next venture: a massive Ponzi scheme. Under the name “Pleasure Time Incorporated,” Larson sold shares in a non-existent American-Indian Lottery, and, by the mid-1990s, he’d managed to cheat 20,000 investors out of $3 million. With the SEC, IRS, and FBI hot on his tail, he fled Ohio and disappeared into the void.

When investigators finally tracked Larson to Apopka, Florida in 1999, he’d succumbed to throat cancer.

***

“Winning that game show was the start of [Michael’s] downfall,” Larson’s brother, James, would later say. “It made him think he could trick anybody, and do just about anything he pleased.”

But it was also a feat that brought out the best in a man who was otherwise a delinquent: Recognizing the board’s flaws required keen observation skills. Mastering the timing of the generator took a unique combination of patience, dedication, and can-do mentality. And performing under pressure in front of a live studio audience demanded a special breed of composure.

In many ways, “gaming” Press Your Luck was the most honest endeavor Michael Larson ever undertook.

For our next post, we explore the probability of marrying a co-worker. To get notified when we post it → join our email list. An earlier version of this post first appeared September 14, 2015.

![]()

Note: Priceonomics can help your company get better at creating content marketing that actually performs. Software, training and content creation services from Priceonomics. Starting at just $49 / month.