San Francisco in the late 1960s was a place for lovers, poets, and peace-makers. Positivity and goodwill were as omnipresent as the fog, and people were greeted with open arms and rosy cheeks. Unless, of course, you were on the second story of Sam Wo Restaurant in the heart of Chinatown.

Past steaming woks and chopping blocks and up a narrow, creaky staircase, Edsel Ford Fong — the world’s most insulting waiter — greeted patrons with a “sit down and shut up!” Routinely, he cussed out his customers, sexually accosted female companions, and unapologetically spilled soup across laps. According to one diner, he was so malicious that he “made the Soup Nazi look like the Dalai Lama.”

But Edsel’s antics also made a legend: people would come to Sam Wo’s just to experience his wrath. In 1982, The Chronicle even deemed the man “San Francisco’s Worst Waiter.” Through oral histories, we’ve recounted who this man was, what it was like to be served by him, and the legacy he left behind.

The Edsel Ford Fong Experience

By the time it closed in 2012, Sam Wo Restaurant had been in business for nearly 100 years. In its prime, the dingy four-story Chinatown joint was legendary — partly for its curry noodles, but more so for the antics of its wait staff. A regular who frequented Sam Wo’s in the 60s recalls the ordeal just to get to the building’s dining room:

“You’d pass through clouds of steam rising from big soup and noodle cauldrons, climb a flight and a half of steep stairs and find a stool at one of the tables in the long, narrow dining room. It was more like the galley on a Liberian registered tramp freighter. No armchair dining here.”

It was a cultural hotspot: celebrities, gamblers, musicians, beatniks, and hippies mingled with Chinese immigrants, and those who didn’t speak the language resorted to pointing to others’ plates and nodding. Plastered on each table, the house rules spelled out the establishment’s no-nonsense attitude — “No Booze, No Jive, No Coffee, Milk, Soft Drinks, Fortune Cookies.” Beside the authoritative words, a stern caricature of Edsel Ford Fong stared you in the eye with a look that negated everything about the restaurant’s literal translation (“Three in peace,” after the original founders).

Edsel, the son of Sam Wo’s owner, began as a waiter and soon became the restaurant’s coming attraction — and for an unlikely reason: he was the rudest, most despotic waiter to ever walk the earth. At 6’, 200 pounds, Edsel sported a military crew cut, a long, perennially-stained white apron, and an omnipresent scowl. When it came to insults, recalls one customer, “he took no prisoners:”

“Mao said everybody eats from the same pot of soup but Edsel let you know he was an ardent supporter of Generalissimo Chaing Kai-Shek.

If there was a line and you weren’t a regular, even if you were at the head of it, you’d have to wait. If you asked questions about the food, Edsel would point to menus tacked to the wall, all in chinese. He would slide your bowl across the table, not minding if some of it messed your pants or shirt along the way. He’d throw the chopsticks onto the table like they were a pair of dice. And to make matters worse, he’d laugh about it, right in your face.”

Joe Franco recalls his first visit to Sam Wo in 1981 and, consequently, his first Edsel experience. “Sit down and shut up!” he was told upon entering. When he made the grave mistake of attempting to order sweet-and-sour pork and a diet coke, Edsel was not pleased:

“You [stupid]? No coke!! Tea Only!! No sweet and sour!! You see on menu?!! You get house special chow fun…No fork, chopstick only…What you want, fat man?”

Another customer, Lou Sideris, once tried to order the “fried shrimp,” an item nearly double the price of anything else on the menu. “No! It’s a rip-off!” yelled Edsel. Sideris and his friends would return many times over the years, each time attempting to order the shrimp, and each time being furiously denied by Edsel.

Even if someone did manage to place an order approved by the waiter, he’d often confuse it with another table’s food, or write down a different item altogether. There was no complaining with Edsel — you ate what you were given, regardless of whether or not it was what you wanted. If you took too long reading the menu, you’d receive a dose of Edsel’s first-class abuse: “What is this, a library?!”

Unless you were a VIP, your meal would be over the second your spoon hit the bottom of the bowl: Edsel would come by with a broom and literally sweep you out. Only one diner — who bought him a “weekly ration of free X-rated movie passes” — was permitted to enjoy a post-meal cup of “Edsel’s Special Tea” (pure ginseng extract). When another customer saw the drink and curiously inquired about it, he was kicked out. This wasn’t unusual: often, Edsel would forcibly remove seated patrons in the middle of a meal, “just to remind them who was running the show.”

For kicks, Edsel would parlay his waiting duties to unsuspecting guests. A first-timer in the mid-seventies learned the hard way. “You want to sit and eat? You clean the plates from the table!” Edsel yelled. For the next 15 minutes, the diner and his party stood at the sink rinsing dishes — just in order to be served. Afterward, in the middle of the party’s meal, Edsel demanded they give up their chairs for some regulars who’d just walked in. They obliged, and ate the rest of their meal standing up. “It was one of the best dining experiences of my life,” recalls the diner. “If you went to Sam Wo’s for anything other than this type of madness, then shame on you.”

Gregory C. Ford, another patron in the late 70s, recalls similar treatment from Edsel:

“Upon entering, Mr. Fong instantly made me wipe the table get water and even fill water for the other tables. Then, he threw the order ticket on the table and had me write down the orders. I handed back the tickets and he threw it down and said ‘ADD IT UP!’ When the food came up from the kitchen, Edsel ordered me to deliver it.”

At the end of your meal, you’d always receive Edsel’s famous line: “small check, big tip!” If you left anything less than 20%, you’d be verbally berated. Edsel put on a show and expected to be compensated like a Hollywood star.

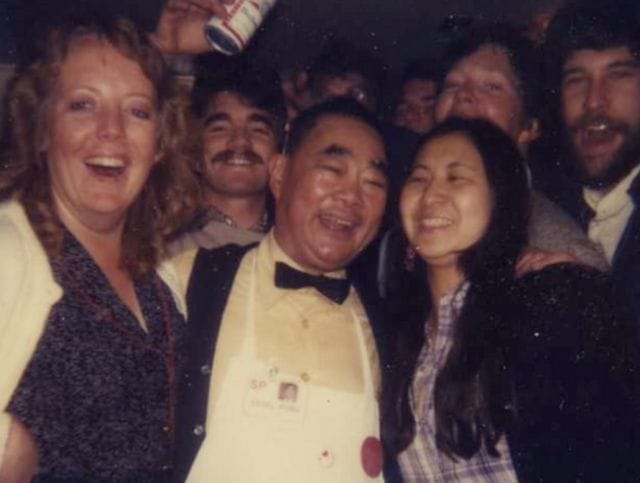

Edsel was also known for his crass “flirtation:” an entire wall at Sam Wo was dedicated to Polaroid photos of the waiter in various degrees of groping unsuspecting young females. “A charming first date destination if you never want to see your date again,” wrote one reviewer in the late 70s. “My ex-wife ended up on the wall. The groping part was the only time I ever saw Edsel smile. She was not amused.” (The pictures we’ve included in this article confirm Edsel’s perennial smile in the presence of ladies — we don’t condone his behavior.)

On numerous occasions, Edsel attracted the attention of local authorities. James Flower, a diner in the late 60s, recalls one particular incident:

“He was serving a tourist family, looked down the young teen daughter’s dress, and said, ‘Hmm, nice little apples!’ They stormed out, returned with a beat cop, who gave Eddie a stern talking to and assured the parents that whatever he was saying in Chinese meant, ‘I’m sorry,’ though he didn’t seem particularly contrite. Edsel was certainly not what you’d call politically correct.”

At times, he’d even make physical contact. A guest in the 80s recounts his sister-in-law’s discomfort:

“Once I was there with my sister-in-law, who is a very proper sort of person. Edsel could really tell when he was pushing someone’s buttons, and he really lit into her. It ended with him thrusting his sweaty, grizzled face right against hers while taunting her with, “Give me a kiss, baby!” Needless to say, she didn’t relish her visit.”

Yet another diner recalls a time Edsel kissed his mother, but brushes it off as an inherent part of the man’s character. “If you knew Edsel, he kissed everybody and even got in a few back during his nightly repertoire!”

Legacy

Edsel passed away in 1984, at the age of 55 — but not before securing an eternal space in San Francisco’s folklore.

Herb Caen, the Pulitzer Prize winning San Francisco Chronicle writer, was a regular lunch customer at Sam Wo’s throughout the 60s and would often publish Edsel’s remarks in his columns. In turn, Edsel would proudly march around the dining room, pointing to his name in the paper; if strangers inquired, he’d “unleash of volley of expletives.”

Edsel was also memorialized in Armistead Maupin’s novel series Tales of the City, where he appears as a no-less-vicious fictional version of himself. In the book, the protagonist is berated by a waiter at a Chinese restaurant for not washing her hands after leaving the restroom: “‘Hey, lady! Go wash yo’ hands! You don’t wash, you don’t eat!’” Flustered, the protagonist returns to her table, where her seasoned companion lets her in on the waiter’s secret: “He specializes in being rude. It’s a joke. War lord-turned-waiter. People come here for it.’”

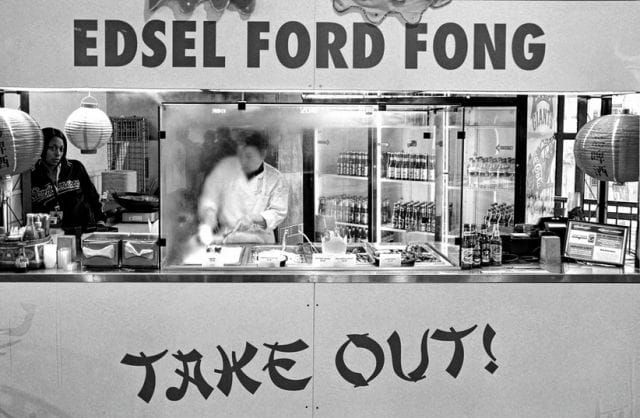

“Gold Mountain,” a San Francisco mural depicting Chinese contributions to American history, prominently featured Edsel (the mural has since been painted over). There is also a club-level Chinese bistro in The San Francisco Giants’ AT&T Park that bears his namesake (though the service isn’t nearly as disarming).

Time after time, Edsel’s customers came back for more abuse: clearly, there was something about this man that transcended his awfulness.

On Saw Wo’s (now defunct) Facebook page, fans leave behind their favorite memories of the restaurant. Jan Bielawski recalls an experience from the 60s that could only be linked to Edsel: “A guest asked to change an order…the waiter screamed ‘You order it, you pay for it, you EAT it!’”

But when she returned in the early 80s, she recalled an Edsel quite removed from his usual bitterness: “I was leaving and for some reason I felt I had to turn around: there he was, at the back of the kitchen, smiling at me. Then, he bowed. I never knew if his anger was genuine or an act, but it was always an experience.”

This post was written by Zachary Crockett. Follow him on Twitter here, or Google Plus here.