As students return to school for the Fall, it’s important to remember that textbooks were not always so expensive.

The College Board recently estimated that the average student spends upwards of $1,200 per year on textbooks. (This figure is much higher for students at for-profit colleges and trade schools.) But American schools in the 19th century used the same books for all grade levels, mainly as a memorization tool. Textbooks then began to take precedence over instructors, as high school and college courses increasingly became structured around a book’s table of contents in the early 1930’s. The books were cheap and were reused for decades; publishers prided themselves on the durability and longevity of their products.

At some point during the 1970s, books started to get expensive. Publishers capitalized on professors’ willingness to adapt new editions of a book every two or three years. Textbooks became less about educating the masses and more about exclusivity and profitability. By the 1990s, the textbook market was an oligopoly, and prices skyrocketed.

***

After extensively complaining about book prices during my time in college, I went on to work for one of the “Big 3” publishers in the United States. A major conglomerate, my company was responsible for publishing nearly a third of all college textbooks and raked in nearly $2 billion in revenue in 2011. But despite apparent success, the company recently filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy. The textbook price debate is more complex than a cursory glance would suggest.

Textbooks have long been criticized by the media and student interest groups for being grossly overpriced. In recent years, used textbook markets and rental sites like Chegg and Bookrenter have pressured major publishers. In addition, open-source textbooks are gaining traction as a viable replacement to traditional alternatives.

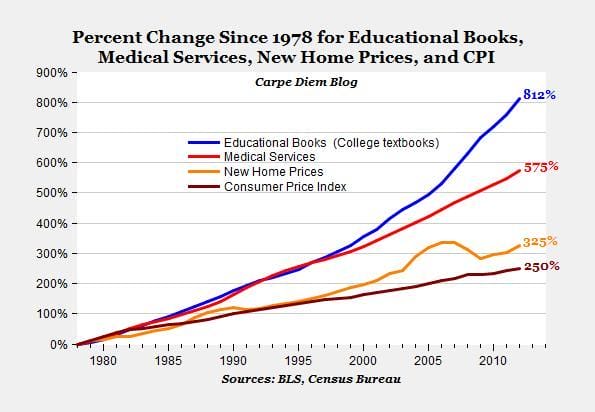

Source: American Enterprise Institute

While much research, marketing, and specialized knowledge factors into the creation of a college textbook, it seems hard to justify an 812% increase in price since 1978 — more than double the increase in home prices over the same time period (see graphic above). What could justify the high cost?

The source of textbook inflation has been the root of much speculation: college bookstores, professors, and publishers have been equally denigrated by the media and student interest groups. However, there is little public information on the components of these costs and how they factor into a book’s cost. To bring some transparency to the question, the following analysis will break down the price of a single college textbook. As an example, I’ll use Introductory Algebra, 4th Edition (Tussy/Gustafson/Koenig), a typical entry-level math book.

Bookstore Markup

When you purchase a book through the campus bookstore, a percentage of what you pay is an additional bookstore markup.

Introductory Algebra, 4th Edition, which retails new for $195.49 direct from the publisher, is sold wholesale to bookstores at a price of $181.50. After purchasing the product for a 7% discount, a bookstore typically sells it at a 25-28% markup. UC Davis’s college bookstore website states:

“New academic books are priced among the lowest of all college and university stores with books billed at net price from the source of supply (publisher, wholesaler, importer, distributor) at a 22% margin (or 28.2% markup).” *

* Note: margin is defined as [(Retail – Gross Cost)/Retail]; markup is defined as [(Retail – Gross Cost)/Cost]

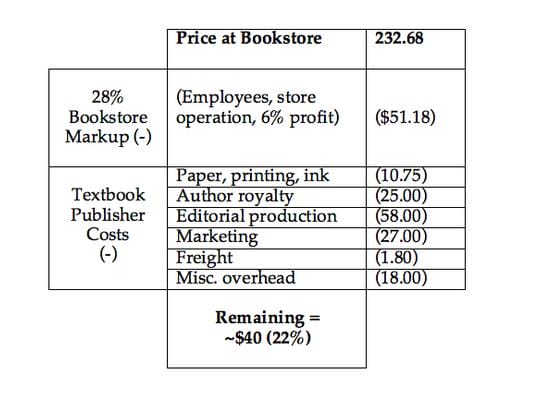

On most college bookstore sites, you’ll find a pricing policy section that will outline similar markups. So, the price you’d pay for that math text at the bookstore would be (181.50) x (1.282) = $232.68.

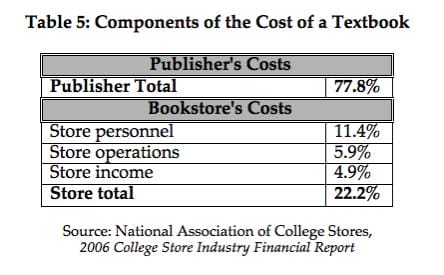

Note that this 28% markup (or $51) must cover the costs of running the bookstore — employee salaries, utilities, taxes, etc. Charles Schmidt, of the National Association of College Stores, claims that, after these costs are considered, college bookstores “make a profit of only 6.3 cents from every dollar spent on a new textbook.” As this data is self-reported to the NACS by the bookstores, it must be taken with a grain of salt. Regardless, profit after overhead for these stores is modest.

The above table touches on the percentages of a book’s price that are attributed to the bookstore and the publisher. While the bookstore’s markup accounts for 22% of the price you pay ($51/$232), the majority of a book’s high price can be attributed to the publisher.

For the remainder of this analysis, I’ll examine the publisher’s costs for Introductory Algebra, 4th Edition at wholesale price ($181.50).

Publisher Costs: Marginal Production Costs: 5%

The common claim of textbook price pundits is that the marginal cost of each textbook is miniscule in comparison to its retail price.

We can understand the “marginal cost” of a textbook to mean the cost of each subsequent book, or the cost to manufacture a single physical product. Marginal cost excludes all other considerations (author royalties, employee pay, marketing, shipping, etc.), and solely focuses on physical production. This essentially boils down to the cost of paper, ink, binding, and printing fees. In its annual report, the publisher of our textbook explains how these costs are controlled and minimized:

“The primary raw material we use is paper. Paper prices may fluctuate significantly from time to time. We attempt to moderate our exposure to fluctuations in price by entering into single- and multi-year supply contracts with multiple paper suppliers and having alternative suppliers available.”

During my time in publishing, our editorial team had access to JDE, a program that provided a breakdown of all marginal costs for any given book. To print this 864-page book — including ink, paper, printing services, and binding — the publisher pays $10.75, or 6% of our book’s $181.50 price tag. Virtually all printing services are outsourced to China, and are done in mass quantities — usually around 10,000 copies per book, depending on projected sales — at wholesale cost.

Author Royalty: 15%

Depending on longevity and previous sales numbers, authors usually receive around 11-15% of a book’s sales. Similar to trade publishing, more established writers command higher royalty rates; I happened to work with the authors of our example text and their contract stipulated a 15% royalty.

For a $181.50 book, the author(s) would take about $25 per copy sold.

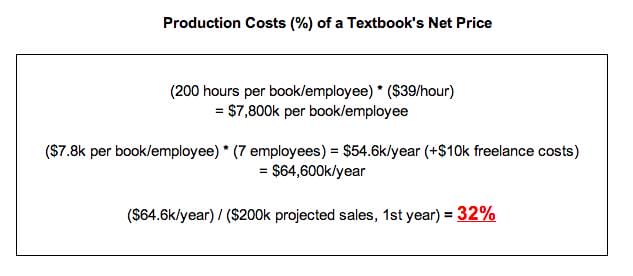

Editorial Costs: 32%

Publishers have trouble quantifying what the editorial cost is for any given book. Acquisition editors commonly exceed editorial budgets, or cut them to provide additional funding for a more cumbersome series. When I left the company, it was revising time sheets so that employees would include how many hours per week they worked on each ISBN (specific book). This was an effort to achieve a rough understanding of how many man-hours were invested into a book; they could then factor this information into production cost to see if there was a correlation between quality and profit.

Using my company’s 2012 fiscal year annual report, I compiled a rough estimate of how production costs factor into a book’s final price. These numbers are speculative, but, based on available information, reasonably accurate.

A textbook company is broken into subject teams that focus solely on a course list. I worked with a team of seven in-house employees on the Mathematics course list, which encompassed 10 books. Our time over the course of a year was split evenly between these ten books. Assuming each employee worked 2,000 hours per year (40 hours per week, 50 weeks per year), each text would get 200 man-hours of attention. Using Glassdoor, I found the average hourly pay on our team to be about $30; to consider the average “fully loaded” wage (including benefits, taxes, and PTO), I’ll add 30% to this, or $9.

With these numbers, we can estimate that, on average, each of the seven employees on our team contributed $7,800 of work per year on a single book, or $54,600 per year total. In addition to this, freelance copy editing and consulting for a new edition amounts to $10,000.

Projected sales for a book of moderate popularity are usually around $200,000 per year, and are based off of field interest and projected adoptions by professors and universities.

In the table below, I show the percent of a book’s price that is used to cover production costs.

So, roughly 32% of our book’s price, or $58, would be used to retribute the salaries of the employees who produced it.

Marketing Costs: 15%

The publisher of our text reported $32 million spent on advertising for all products company-wide; overall, about 15% of a publisher’s budget for a book is dedicated to marketing. This includes book fairs, paying field sales representatives, the cost of free copies given to authors and professors, and any other promotional fanfare (publishers’ conferences, advertising, travel).

So, for our book, roughly $27 is used to cover these costs.

Freight: 1%

Publishers move thousands of books a day during the school year, and there is always a high volume of material being transported between inventory, sales offices, and schools. Even so, shipping only accounts for 1% of costs. For each $181.50 book, the company would pay roughly $1.80 to ship in bulk.

General Company Overhead: 10%

This is a vast, complex category, as publishers have many other fees that contribute to overhead. To determine earnings made from a book after all aspects of production are considered, I will exclude taxes, interest, depreciation, and amortization costs.

The company spends about $200 million per year on property fees (they own 38), utilities, licensed software, and general office expenses. Advisory fees and other obligatory company costs are an additional $10.7 million per year, bringing our approximate overhead total to $211 million, or 10% of the company’s $1.9 billion sales revenue.

About $18 from each copy of our book sold would cover these costs.

Profit

So, what’s left?

Accounting for the production and marginal costs listed in the company’s annual report and external resources, we are left with a $40 profit — about 22% of our book’s wholesale price. From this profit, taxes and other costs (depreciation, amortization) must be drawn, but this figure provides us with a profit margin from the sale of an individual unit.

Despite attractive numbers, our publisher took in only $18.2 million in net income in 2012 — less than 1% of its $1.9 billion in reported revenues. In 2011, the company fared even worse, reporting negative income. How did a company with significant profit margins take in so little cash from its operations and file for Chapter 11 bankruptcy?

The answer is debt driven by acquisitions. In 2008, in an effort to compete in an increasingly digital market, the company made a slew of acquisitions. These purchases bloated their debt from $768 million to $6.29 billion in one year (2007-2008); by the 2012 fiscal year, they reported total assets of $7.5 billion, and a debt of $5.7 billion.

This debt also has an impact on how we interpret the company’s reported $18.2 million net income for 2012. Over the past the past two years, they have paid off $687 million in debt, and $915 million in interest expenses, sucking away much of their revenue.

This leaves our original question unanswered. Are textbooks’ high costs necessary? Or could the industry be much more frugal?

Conclusion

The media, student bodies, and prominent politicians have all decried publishers, who they claim have lost touch with what’s in the best interest of students. The New York Times has even likened the textbook industry to the pharmaceutical market, a concept expanded upon by Caltech economics professor and open-source advocate R. Preston McAfee:

“The doctor who prescribes medication and the professor who requires a textbook don’t have to bear the cost and thus usually don’t think twice about it. There is this sort of creep. It’s always O.K. to add $5…this market is not working very well — except for the shareholders and the textbook publishers. We have lots of knowledge, but we are not getting it out.”

Textbook publishers realize the largest profit margins from new editions, which come out every 2-4 years, are minimally updated, and are sold at the same price. Generally, a new cover is designed, copy errors are fixed, and a few sections may be revamped. The investment required for subsequent editions is miniscule. Hence, the topic of debate when it comes to book prices is often whether or not new editions are worth as much (or even more than) previous editions.

Most of the time, the answer is no — especially with math and other technical books, in which the content does not warrant frequent updates. However, publishers survive by eradicating used books and sweet talking professors into adapting new editions. More often than not, the professors oblige.

Due to this cycle, many agree that textbooks have contributed to the “crisis of access” in today’s higher education system. Growing dissent has sparked an open-source movement that is quickly gaining traction across campuses. OpenStax College, Flat World Knowledge, and other nonprofits aim to dismantle the traditional textbook model by developing free, community-driven textbooks.

If the impending threats of online textbook markets and open source information aren’t enough to stress traditional publishers, Washington is now taking a stab at dramatically reducing book prices. The Affordable College Textbook Act, filed in Congress earlier this month by Dick Durbin (D-Ill.) and Al Franken (D-Minn.), proposes to provide federal grants to aid the creation of open-source databases.

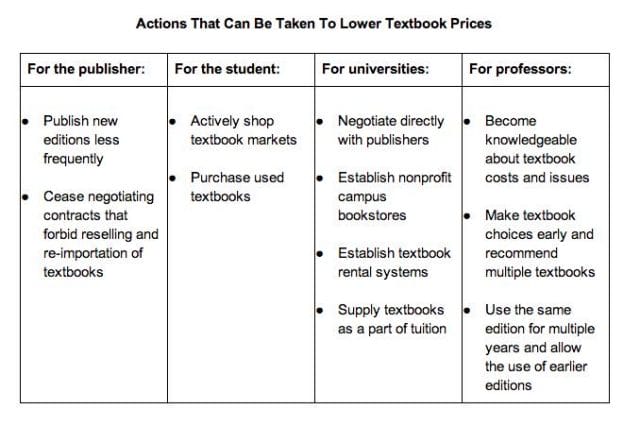

So, what needs to be done in order to change the current model? Dr. James V. Koch, an economics professor and fierce opponent of the textbook industry, has several suggestions:

One more suggestion can be added to the list for students, professors, and universities: Remember that life isn’t learned from textbooks, and that an education can sometimes be richer without them. As educator and political activist John Hope told us, “we must get beyond textbooks, go out into the bypaths… and tell the world the glories of our journey.”

This post was written by Zachary Crockett. Follow him on Twitter here, or Google Plus here.