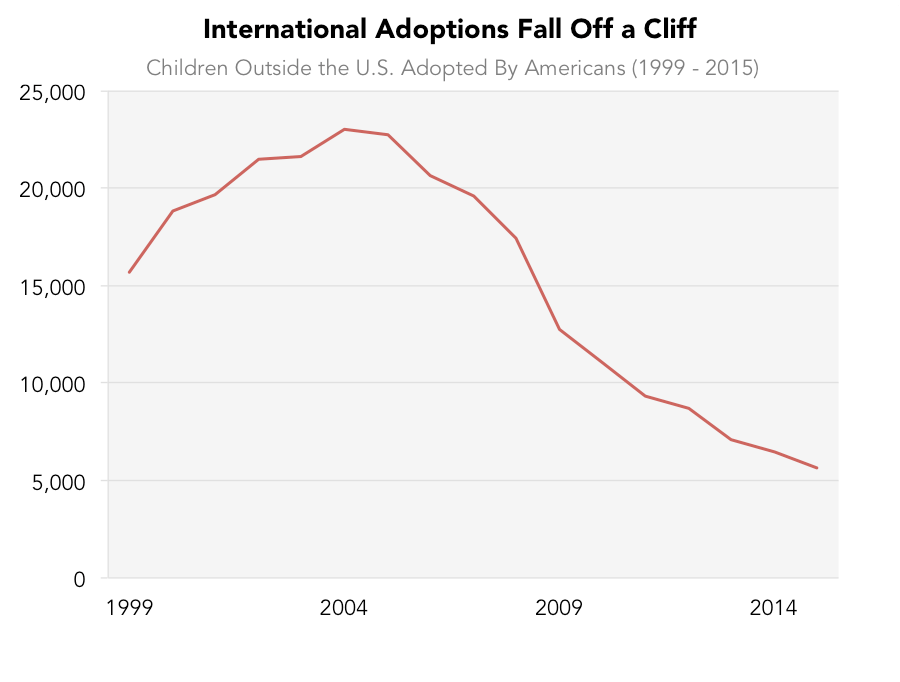

Adoption expert Elizabeth Bartholet calls it “the cliff.”

It started in 2004, a year in which Americans adopted nearly 23,000 children from overseas. That was a record-breaking year for international adoptions in the U.S.—but so was the year before that and the year before that. With few exceptions, adoptions from abroad had been rising steadily since the end of World War II.

But then something changed. From its historic peak in the mid-2000s, the number of international adoptions began to fall. It has been falling ever since. According to figures collected by the U.S. State Department, Americans adopted 5,647 children from other countries last year, the lowest figure since the early 1980s. That is a 75% decline in just over one decade.

Data Source: U.S. State Department Intercountry Adoption Statistics

The change has happened quickly, but the momentum behind it has been building for decades. Starting in the 1980s, a growing list of countries around the globe started tightening regulations and imposing moratoriums on foreign adoptions.

These reforms have not been coordinated per se. In some cases, accusations of baby selling and other unsavory child adoption practices have led countries to shutter their programs. In others, countries have acted at the behest of humanitarian NGOs who argue that a child should only be wrenched away from extended family and community when all other remedies have been tried. And in a number of instances, countries have restricted foreign adoptions as a chest-thumping exercise to assert their economic strength or political independence.

But taken together, the global tightening of the international adoption “market” represents a sea change in global child welfare policy. Though the practice is often viewed in developed countries as an unalloyed good—a way to simultaneously help poverty-stricken orphans on one side of the globe, and aspiring parents unable to conceive, on the other—a new, more ambivalent consensus is emerging that views international adoption as, at best, a necessary evil and a last resort.

Adoption Trends: A Brief History of Conflict and Disaster

The ebbs and flows of international adoptions in the United States have always been shaped by geopolitics.

Until the Second World War, the concept of a foreigner visiting a country with the explicit purpose of finding a child to bring home as one of their own was unfamiliar to most Americans. But as newspapers and soldiers brought word home of the war orphans of Europe and Asia, adoption emerged as a family-centric complement to the Marshall Plan.

These adoptions, often organized by American church groups, were not particularly common, but they introduced the notion to the public as a new kind of charity. The Family That Nobody Wanted, a memoir written by the adoptive mother of 12 mostly foreign-born children, became a runaway success in 1954.

By that year, the Korean War had come to an end, and once again sympathies for war orphans led to a spike in adoptions from the peninsula. Despite having no cultural precedent for American-style adoption, this trend was actively encouraged by the newly formed government of South Korea, which quickly put together a Child Placement Services agency in order to shepherd the unwanted progeny of Korean women and American soldiers out of the country. This program developed a reputation among adoption agencies in the United States and Western Europe as a “reliable source” for young, healthy infants. South Korea remains one of the top “sender” countries for U.S. international adoptions to this day.

Following the same pattern, there was also a spike in American adoptions out of Vietnam in the mid-1970s. This episode is associated with the famous (and for many, infamous) “Operation Babylift.” As South Vietnam was falling to the North in the spring of 1975, President Ford ordered cargo planes to ferry 2,500 children out of Saigon. The goal was to save these children, who were placed with adoptive families in the United States and elsewhere, but it was later discovered that many were not in fact orphans.

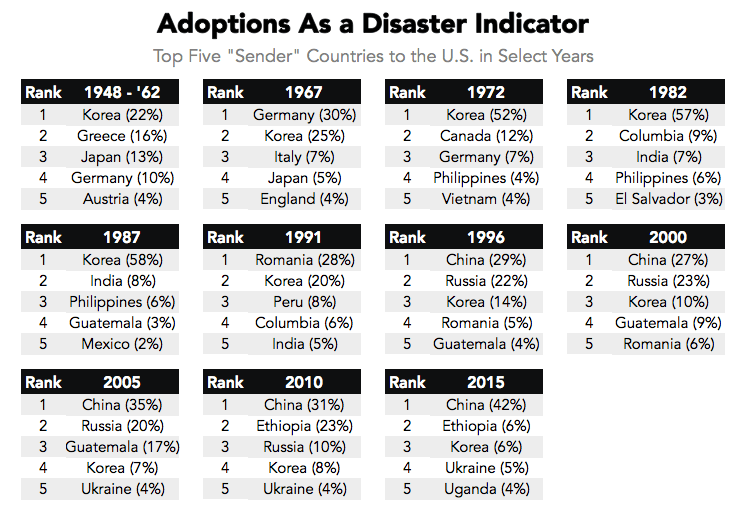

American adoptions don’t just follow American wars, but all types of global tragedy. An overview of the top five source countries for American adoptive parents over time serves as an abridged guide to international conflict and deprivation in the 20th century.

Data Source: Peter Selman and U.S. State Department Intercountry Adoption Statistics

The success of German economic reconstruction is signaled by Germany falling from the list of common “sender” countries. In the 1980s, civil war and poverty in Central and South America are reflected by an uptick in American adoption rates from El Salvador and Guatemala, and in the 1990s, we see the fall of the Iron Curtain in the rise of Romanian and Russian adoptions.

These figures are a strange lens through which to view the American public’s changing understanding of the world. But the fact that American adoption trends tend to track with conflict, disaster, and destitution also reflects a fairly obvious point: Americans adopt orphans from countries that are full of adoptable orphans.

In recent years, there have been far fewer orphans to be found at home. Since the 1970s, access to birth control, the legalization of abortion, falling fertility rates, and the acceptability of single parenthood have reduced the number of adoptable infants within high-income countries like the United States. This has not been an across the board reduction. As some experts have pointed out, though there has been a steep decline in the number of healthy, white infants surrendered for adoption, older children, children with disabilities, and African American children are still considered “difficult to place.” According to the most recent data from the Department of Health and Human Resources, of the over 100,000 children waiting to be adopted in the United States, 87% were at least two years old and over half were not white.

Nevertheless, over the last four decades, straight couples who are unable to have children, single parents, and gay couples have increasingly turned abroad. And that demand has always followed the supply.

Supply Side Constraints

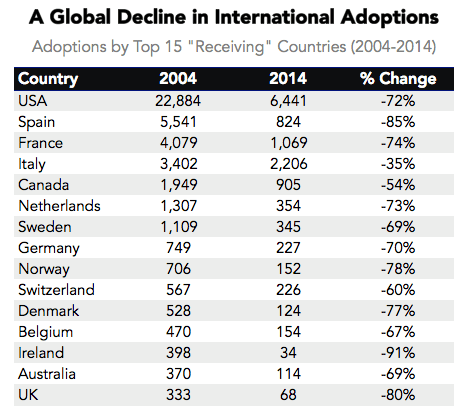

Recently that supply has started to shrink—and not for Americans alone.

According to data gathered by Peter Selman at Newcastle University, parents in each of the top 15 “receiving” countries are bringing far fewer children home now than they were in the mid-2000s. This is not for lack of desire, he says.

“It’s not that the numbers are falling dramatically because there’s no demand for them, that there are all these children waiting to be adopted and nobody wants to adopt them,” says Selman. “It seems to me a matter of supply. The ‘sending’ countries are increasingly worried about pressures from receiving states and about continuing examples of illegality or profit-driven actions.”

Data Source: Peter Selman

Such examples always grab headlines. In the chaotic aftermath of the fall of the U.S.S.R., aspiring adoptive parents from the United States and Western Europe flocked to the infamously squalid orphanages of the former Soviet satellite state of Romania. Though the country adopted stringent adoption regulations on paper, its child welfare institutions were not up for the task, and in the years that followed, horror stories emerged. In 1991, the New York Times magazine ran an article called the “Romanian Baby Bazaar,” which documented a lucrative, under-regulated market for infants and children. Ten years later, Romania, in the face of mounting criticism, shuttered its international adoption program.

Romania’s is an egregious, but familiar story. Since the late 1980s, similar scandals have led to the imposition of restrictions and adoption moratoriums in South Korea, Cambodia, Guatemala, Vietnam, and Nepal, among others countries.

Abuses do not occur solely in so-called “source” countries. An investigative report published by Reuters in 2013 found more than 180 online advertisements posted by parents who expressed adopter’s remorse and were seeking “private re-homing” for the children that they had brought home from abroad. According to the report, these extralegal transfers of guardianship often led to the sexual or physical abuse of the children. A particularly notorious example of re-homing came to light last year when Arkansas state representative, Justin Harris, sent two of his adopted daughters to live in the home of a family friend, where one of them was raped.

But according to advocates like Elizabeth Bartholet, faculty director of the Child Advocacy Program at Harvard Law School, though abuses in source and recipient countries grab headlines, they are exceedingly rare. And when the alternative to foreign adoption is institutionalization or worse, she says, the benefits far outweigh the minimal risks.

“There is very little evidence that more than a very small percentage of international adoptions involve anything that would be illegal,” she says. “Whereas there is tons of evidence that the kids that are locked up in institutions and aged out of institutions are the ones that are especially likely to be exploited or trafficked.”

Whose Best Interest?

Tighter regulations on foreign adoptions are not always motivated by scandal. In 1993, the Hague Convention on the Protection of Children and Co-operation in Respect of Intercountry Adoptions was written to place the otherwise fragmented and ad hoc international adoption process within a universal legal framework.

As dozens of countries have signed the international treaty in the intervening years, many “sending” countries and international aid organizations such as UNICEF have promoted a specific interpretation of the treaty: international adoption should be considered only when all other alternatives have been tried.

The Hague Convention has hardly been cure all for corruption and abuse. Romania ratified the treaty in 1995, and allegations of shady dealings continued after. But with many high-income receiving countries signing on, including the United States, sending countries around the world have either been compelled to impose new restrictions on foreign adoption. In 2008, the U.S. State Department ceased approving adoptions from Guatemala in response to widely reported abuses.

But the Hague Convention has also enabled countries to unilaterally impose their own restrictions. After ratifying the treaty in 2006, China imposed a battery of new regulations on foreign adoptions. Though the language of the Hague Convention is intended to ensure that all international adoptions are carried out “in the best interests of the child,” Harvard’s Bartholet says the Chinese restrictions had an entirely different motive.

“They want to make a statement about how they’re no longer a third world, but a first world nation,” she says. “One way to make that statement is to say: We can take care of our own kids. We don’t need you.”

Whatever the motives, a growing number of countries have instituted a common set of stricter adoption policies in the last two decades, such as mandatory waiting periods, residency restrictions for adoptive parents, and instructions that social service authorities seek domestic adoption, domestic fostering, and even informal arrangements with extended family members before considering foreign parents. The Chinese regulations imposed in 2006 went one step further by banning adoptions by foreigners who were unmarried, over a certain age, over a certain weight, or taking antidepressants.

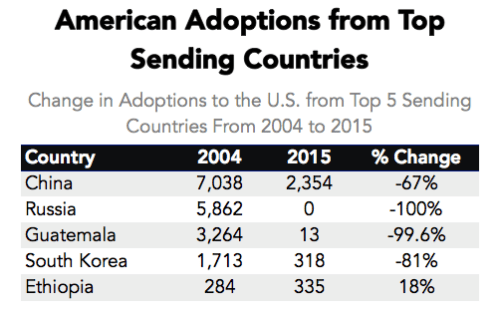

There is often a nationalistic bent to these types of policy. In 2012, the Russian government imposed an absolute adoption ban on all U.S. citizens. Though the law was ostensibly passed in response to the death of a Russian-born toddler while in the custody of his American adoptive father, many observers saw it as an act of retaliation against American financial sanctions from earlier that year. American adoptions of Russian children had been falling prior to the ban from a peak of 5,862 in 2004. The law brought the figure down to zero.

Data Source: U.S. State Department Intercountry Adoption Statistics

But according to a UNICEF report from 2014, the mere prioritization of domestic custody is not only justified, it’s exactly the way that many receiving countries—such as Canada, Italy, the Netherlands, Sweden, and Greece—treat their own orphaned or abandoned children.

“It is apparently assumed that in devising their policies those countries are justified in deciding that, as a general principle, the best interests of their children will not be served by non-relative adoption abroad,” writes the report’s author, Nigel Cantwell.

And if that’s good enough for Canada, these critics argue, why not Cambodia?

Not Just How Many, But Whom

The dramatic shift in international adoption has not only been one of quantity, but also of kind.

An unhappy but predictable reality of adoption—both foreign and domestic—is that adoptive parents have specific preferences for the children that they adopt. Namely, most parents want a healthy infant who has no memory of their home country, no attachment to their birth parents, and who is without disability. When countries place foreign parents at the back of the queue for adoptable children, they guarantee that a much higher proportion of these children will not fit this description.

This has certainly been the case in China, a country that has provided the largest number of adopted children to the United States in recent years. Amidst a general move to encourage domestic adoption and restrict adoption by foreigners, the Chinese government announced a plan to formally roll back the country’s longstanding one-child policy last year.

“Once that was done, they realized there was a big demand for domestic adoption that could easily take up the young, healthy children available,” says Selman from Newcastle University. “What we’re seeing now is that the children adopted [by foreigners] from China are older, in sibling groups, or have some sort of special need.”

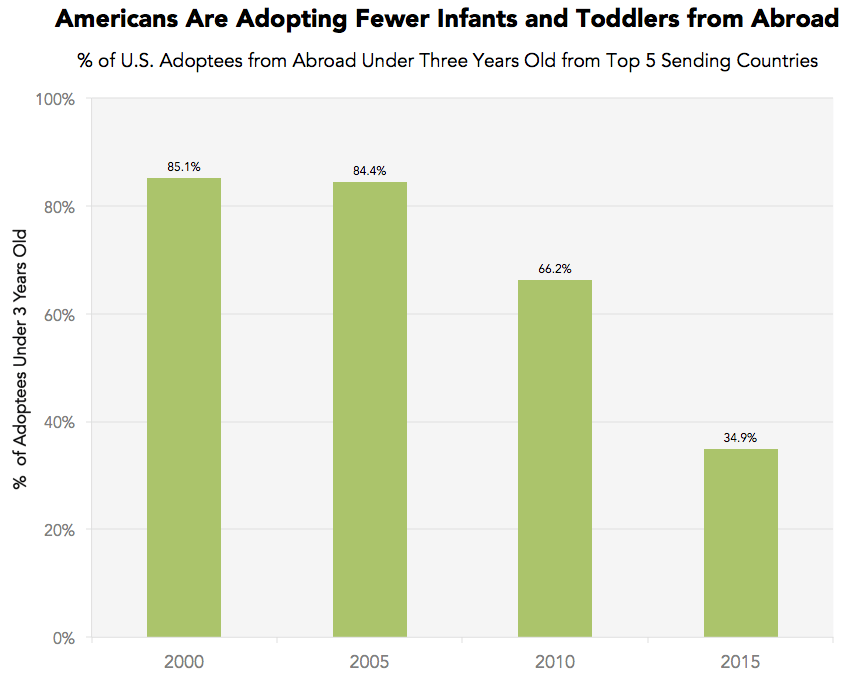

What is true in China has been true among many sending countries. In 2005, nearly 85% of the children that Americans adopted from the most common source countries were younger than three years old. In 2015, the proportion was only 35%. This is not the result of an increase in the adoption of older children, which has in fact fallen modestly. But the adoption of infants and toddlers has fallen by much more—92%. When we talk about a “cliff” in international adoptions, this is it.

Data Source: U.S. State Department Intercountry Adoption Statistics

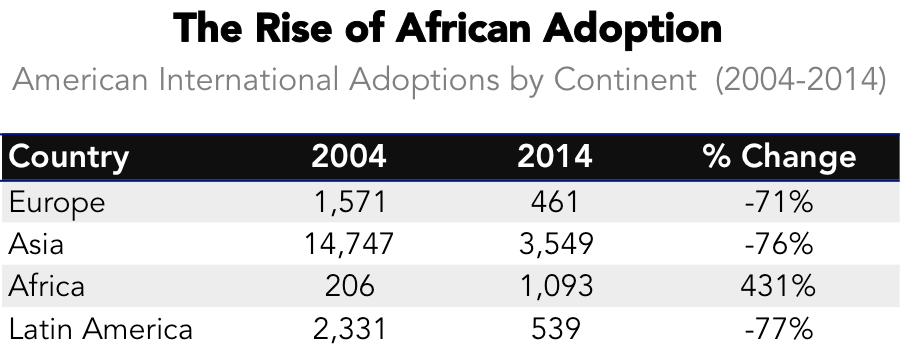

This is part of the reason why American adoptive parents are increasingly turning towards countries like Ethiopia, Uganda, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo. These are countries where poverty, limited social services, and few institutions for domestic adoption have created a relatively high number of adoptable children.

They are also disproportionately “non-Hague” countries (only three countries in Africa have ratified the treaty). Thus, as Americans and other foreign adoptive parents have turned to Africa, stories of child trafficking and unscrupulous adoption agencies have increased accordingly.

Most recently, Ugandan adoption organizations and orphanages have been accused of misleading biological parents into signing away legal guardianship of their children. According to Newcastle’s Selman, formal adoption as it exists in the United States and Europe is not a familiar concept in much of Africa. Many families may be placing their children and other young relatives in “orphanages” without fully understanding the implication of that choice.

Following a familiar pattern of scandal and reform, Uganda signed new restrictions on foreign adoptions last month.

But according to Selman, the rush to Africa is once again a simple matter of demand chasing supply.

“The market changes,” says Selman. “China goes down. Russia begins to get difficult. The number of children available in Thailand and Guatemala reduces substantially and so suddenly there’s an interest [in Africa].”

Data Source: U.S. State Department Intercountry Adoption Statistics

In the meantime, the shortage of adoption opportunities worldwide has also encouraged an increasing number of parents to seek out entirely different alternatives. Children born as a result of international surrogacy now outnumber international adoptees, says Selman. And there is no Hague Convention for cross-border surrogacy.

Coming Home and Asking Questions

Over the course of the last decade, we have witnessed an unprecedented decline in international adoptions. These are thousands of children who might have otherwise been raised in an American, Spanish, or French home, who have instead spent their childhood in their often very poor countries of origin. This presents the non-expert public with a conundrum: is this a global pandemic of child neglect or the end of one?

According to Harvard’s Elizabeth Bartholet, the dramatic decline in foreign adoptions is a silent human rights catastrophe.

“That drop-off represents the tens of thousands of kids every year who used to get loving, nurturing homes and now aren’t getting them,” says Bartholet. “I think it’s rank hypocrisy to talk as if these [restrictions on adoptions] are justified in terms of the child’s best interest.”

The counterargument made by many humanitarian groups and policymakers is that sordid orphanages or homelessness is not the only alternative. Given that foreign adoption wrenches children from their extended families, their communities, and their cultures, they argue, it should be considered only when all other alternatives fail.

In South Korea, this argument has been made especially forcefully from a surprising quarter: the adoptees themselves. Two-thirds of the nearly 200,000 children that have been adopted from Korea since 1954 are now over the age of twenty. Since the late 1980s, when international adoption first became a hot button issue following a series of scandals during the Seoul Summer Olympics, many adoptees have returned to Korea and set to lobbying the government.

“I don’t think it’s normal adopting a child from another country, of another race and paying a lot of money,” Kim Stoker, an anti-adoption activist, told the New York Times magazine in 2015. Stoker is one of thousands of Korean adoptees that have pushed for more restrictions on adoptions and more financial support and social acceptance for unwed mothers. “I don’t think it’s normal to put a child on a plane away from all its kin…it’s a very modern phenomenon.”

Korea has the longest running national adoption program in the world, and so it is hardly surprising that so many adoptees are now returning to the country of their birth and asking questions about the details of their separation. But as more children who have been adopted from Eastern Europe, Southeast Asia, Central America, and Africa come of age, we should expect them to start similar conversations.

That will make for some complicated moral arithmetic. The vast majority of the children who are adopted by parents in the United States and other common receiving countries are raised in what Elizabeth Bartholet calls “loving, nurturing homes.” For the adoptees who were taken from countries plagued by poverty or war or illness, it is easy to see what they have gained through their adoption. But how will they ever know what they have lost?

Our next article explores the largest (and worst) tax break in America. To get notified when we post it → join our email list.

The cover image comes from Tawheed Manzoor.

![]()

Want to write for Priceonomics? We are looking for freelance contributors.