Flip through a popular bridal magazine these days and you’ll find a sea of smiling women, twirling in white.

The white gown is synonymous with weddings, a custom that’s often assumed to be a nod to old-school values of purity and chastity, as embodied by the virginal bride.

But in reality, the rise of the white dress is less a story of religious influence or puritanical mores than it is a tale of economics and marketing – one driven by a burgeoning garment industry that managed to harness the power of WWII propaganda and the marital boom that followed.

“The color of the twentieth-century gown itself was an invented tradition, meaning that it evolved into something seen as unchanging and timeless, though it was not always so,” writes Vicki Howard in her book, Brides, Inc.

Though considered a historic and time-honored ritual, the white wedding is actually a somewhat modern phenomenon.

Aristocratic origins

For many women throughout history, a wedding dress wasn’t a once-worn garment in shimmering white, but simply the nicest item of clothing they had. In many cases, they’d wear it again for other formal occasions, some of them less celebratory in nature.

“Most nineteenth-century brides were simply married in their best dress, which was often black (durable and appropriate for inevitable funerals),” writes Carol Wallace in her history of the ceremony, All Dressed in White.

For most of human history, those of lesser means were wise to avoid white – in addition to being expensive, white fabrics weren’t exactly easy to keep clean. Since wedding gowns were typically used on multiple occasions, this was a particularly important consideration. Women often made their own dresses at home, and any faulty stitches or imperfections would be more likely to stand out in white.

Still, there’s evidence of royalty sporting the color dating back to the Middle Ages.

Princess Philippa of England reportedly donned white satin trimmed with ermine (a type of weasel) for her 1406 wedding to a Danish prince, likely the first documented case of a princess in white on the big day.

A bride in a dark wedding dress. Photo credit: Lindner, Chicago

The color gained a significant PR boost when Queen Victoria of England chose a white satin and lace gown for her marriage to Prince Albert in 1840. As the most public royal wedding to date, news of the event, including engravings of the queen, quickly made the rounds.

A trend had begun to take root, although it would be another hundred years before the style would be widely available to middle class women at an affordable price.

A portrait of Queen Victoria in her wedding dress. Photo via Wikipedia

Brides from elite families in England and the U.S. began to adopt the color in the decades following the queen’s debut until, just fifty years later, it seemed as though the custom had always been: “From times immemorial the bride’s gown has been white,” claimed an issue of Ladies’ Home Journal in 1890.

By the turn of the century, the wealthy still had a monopoly on the white wedding dress, even as the color choice took on new significance: underscoring a bride’s sexual purity. That likely wasn’t Queen Victoria’s intent. But after her trendsetting nuptials, as one journalist has written, “the sentimental Victorians idolized innocent brides and their pure white gowns.”

“Custom has decided, from the earliest ages, that white is the most fitting hue, whatever may be the material,” declared the Godey’s Lady’s Book in 1849. “It is an emblem of the purity and innocence of girlhood, and the unsullied heart she now yields to the chosen one.”

Nevertheless, Vicki Howard argues that it’s not clear whether the brides themselves were adopting the same cultural message or just following the fashions of the day. “Wearing white,” she writes, “simply could have been the thing to do because it was what others were wearing, and had worn in the past.”

Soon, the ritual of the white dress would reach new heights.

Wartime Weddings

It took a world war to turn the wealthy’s obsession with chaste, white dresses into an institution that crossed class lines.

The early 1940s proved to be a time of sacrifice and scarcity with the onset of World War II. Rations imposed limits on a host of goods, including silk, a popular wedding dress material for those who could afford it.

The military began using silk to build parachutes, although in an endearing twist, there are a number of recorded tales of women crafting wedding dresses out of the parachutes carried by their betrothed.

While marriages themselves were sometimes postponed or pared down during the war, the ritualistic significance of the white wedding was on the rise.

Though women were encouraged to enter the workforce to fill the jobs left vacant by men at war, they were also held up as symbols of what the country’s soldiers were fighting to protect—and what they would come home to when the battles ended.

Government propagandists initiated the effort to motivate Americans by describing the war as a fight for marriage and family, but manufacturers and retailers quickly picked up on the trend.

One government-sponsored radio broadcast from 1942 emphasized that the war was “about love and gettin’ hitched, and havin’ a home and some kids, and breathin’ fresh air out in the suburbs.” Meanwhile, Eureka, the vacuum company, writes Katherine Jellison in It’s Our Day, sold women on the idea that “you’re fighting for a little house of your own, and a husband to meet every night at the door.” Even soap manufacturers capitalized on the zeitgeist.

“The public rhetoric of the war,” writes Nancy Cott in Public Vows, “while dwelling on the defense of democratic freedom against Nazi aggression and Japanese imperialism, emphasized the intimate, private and familial aspects of the American way of life, centering on heterosexual love and marriage.”

This trend intersected perfectly with the bridal industry’s aims. For years, it had tried to convince Americans that a proper wedding called for a new, one of a kind gown.

As an example of these marketing efforts, Vicki Howard writes in Brides, Inc. about a bridal consultant handbook from the era, published by Mademoiselle. “Wearing an heirloom wedding gown simply because it is old or simply because it has sentimental value,” it cautioned in profit-maximizing tones, “does not guarantee a beautiful wedding day.” Such a gown could potentially impose on a bride’s “inalienable right” to look her best for the ceremony.

Advice from etiquette guides and fashion designers spun a similar message, and by the 1930s, Howard writes, the tradition of a bride wearing her mother’s dress had begun to wane.

The bridal industry’s campaign against inherited and homemade wedding dresses culminated with marketing that took advantage of wartime propaganda.

Take one 1942 advertisement from Brides magazine, entitled “Your Right to a Wedding.” The ad, for the Bridal Makers of New York, describes the importance of “one day above all others.” It soothes women with visions of a “glorious sweep of white” and assurances that “when this war and its restrictions are long forgotten, the memory of your day will shine through all the years.”

Indeed, wedding gowns “were seen as part of the war effort – what the country was fighting for,” Vicki Howard writes in Brides, Inc.

The industry even established its own trade group, the Association of Bridal Manufacturers, which successfully fought for an exemption on silk rations for use in wedding dresses, arguing that it would boost morale.

One member of the group reported later that it largely focused its efforts on a single congressman: “We told them, ‘American boys are going off to war and what are they fighting for except the privilege of getting married in the traditional way? They’re fighting for our way of life, and this is part of our way of life and the government is taking it away,’” writes Jellison.

“By invoking ‘tradition’ to justify its exemption from wartime restrictions, the association actually promoted a new cultural norm,” Jellison adds. “Without a factory-produced bridal gown, a ‘real’ wedding simply could not take place.”

By the middle of the twentieth century, the marketing of the wedding dress had transformed it into a sacred garment to be used just once.

Thanks in part of wartime research, more women were soon able to justify that one-time investment.

Post-War Boom

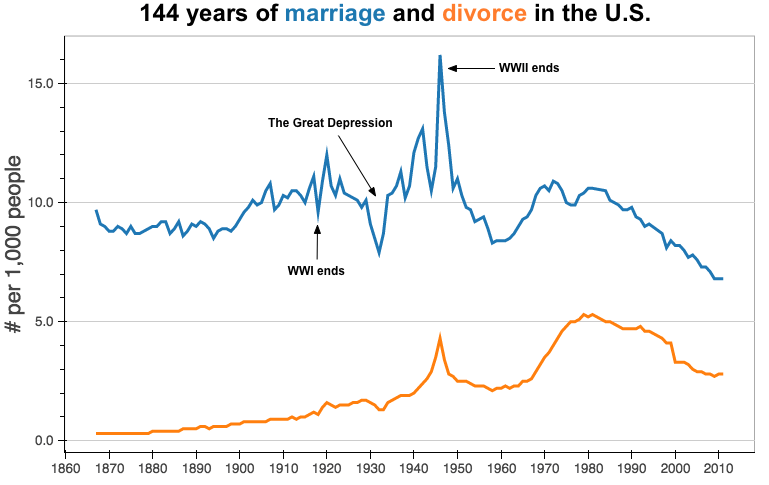

Marriage rates soared after the war, and thanks to the wedding industry’s careful positioning, it was ready to meet the demand spurred by wartime ideology.

More people were entering the bridal shop business, now generating billions of dollars in sales, boosting the industry’s advertising about the significance of the celebration and the need for a formal white gown.

Chart by Randy Olson using data from CDC NCHS

“With her bridal crown and floor-length gown, a woman looked like the princess she saw in books and movies,” writes Jellison. “And like them, she now held an exalted position. She was assuming her sanctioned postwar role of becoming a wife.”

Technological advances played a key role in making the gowns more accessible. What had begun as a fashionable tradition for the elite would now be fully accessible for everybody.

“The first step in the definitive democratization of the white wedding gown was the development and, more importantly, refinement of synthetic fabrics,” writes Carol Wallace in All Dressed in White.

Manufacturers had begun developing synthetic fibers as early as the 1930s, but much of the production shifted to military purposes during the war. Wartime research accelerated the development of synthetic fibers, which were used for making parachutes, tents, and ropes, and improved the fibers’ quality while driving down costs. When peacetime resumed, manufacturers found that bridal gowns were a uniquely good fit for the burgeoning supply of the materials: the fabrics were far less expensive and easier to deal with than satin and silk, making the dresses more widely available. Saks department store, Wallace notes, advertised in 1950 a long-sleeved satin gown with a train for $250 in silk compared with $185 in rayon.

“By 1947, silk was again available, but only for the most expensive gowns,” she writes. “Why would a girl bother, when the synthetics were so appealing?”

Industrial and consumer giants like Du Pont and Joseph Bancroft and Sons Company launched their own ad campaigns for the new materials.

A 1948 Life magazine ad for Du Pont’s new nylon fabrics, for example, shows an illustration of a bride in her white gown tossing a bouquet: “Lighter, lovelier, more radiantly right for the bride than bridal gowns have been,” it says.

A little later, Joseph Bancroft and Sons Company, which manufactured rayon and other synthetics, helped sponsor the 1960 Miss America contest, photographing the winner – and later, her successors – in their “dream” wedding gowns, to be promoted in department stores across the country.

A window display at Macy’s Herald Square location in New York City promoting the Miss America bridal gown. Photo credit: The Hagley Museum

At the same time, a decades-long rise in ready-made, as opposed to custom dresses, helped bring down costs as well. There were a dozen large bridal manufacturers in the U.S. by the mid-1940s and, thanks to the marital boom that followed the war, the number of factories grew to about one hundred by the end of the 1960s.

Even as the conformity of the early 1960s gave way to the sexual revolution and the rise of mainstream feminism, the white wedding gown continued to reign. According to Jellison, the vast majority of women still reported wearing white or ivory for their ceremonies in the early 1970s.

She cites the publisher of Modern Bride, who at the time noted, “Each year there is even a higher rate of white wedding gowns sold than is accounted for just by the increase in the number of marriages. More and more people are having formal weddings every year. It astonishes even me.”

The countercultural uprising of the 1960s took aim at a number of social norms, including some of the assumptions around a woman’s role in the home, but it still failed to unseat the white wedding.

Today, the dress may no longer symbolize virginity, if it ever did, but it’s still considered central to the festivities. Several years after David’s Bridal, the behemoth wedding discount chain, introduced colored wedding dresses in 2010, they accounted for just 4 to 5 percent of bridal gown sales.

And while a growing number of women now adopt non-white gowns, the decision is still considered remarkable, fodder for countless trend pieces.

For a tradition fueled in large part by World War II propaganda and wartime research meant to build more parachutes, the white wedding dress is a remarkably enduring element of American culture.

Our next article uses data to identify TV shows that were cancelled before their time. To get notified when we post it → join our email list.

![]()

Announcement: The Priceonomics Content Marketing Conference is on November 1 in San Francisco. Get your early bird ticket now.