In 1251, the Abbot of Meaux and the Abbot of St. Mary’s of York fought over who owned several profitable businesses. Although the abbots did not brawl, it was a literal fight.

In accordance with English law, since the courts failed to resolve the ownership question, they chose to settle it through trial by combat. Each abbot hired a champion—there was an established market for champions, the best of whom had reputations that scared the other side into settling the case—to fight for his claim.

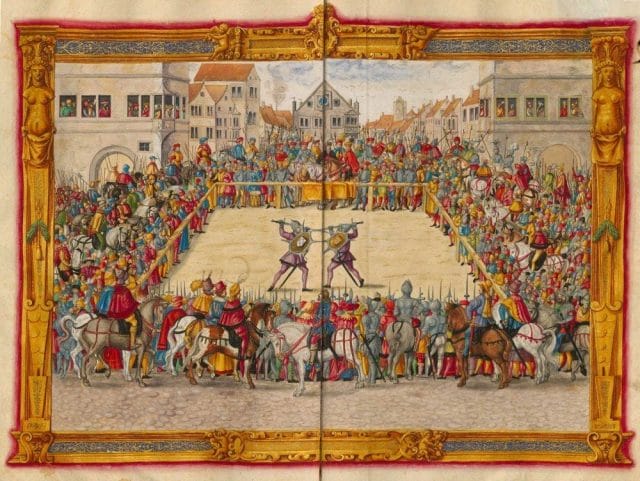

People did not view this as barbaric; it was part of the legal process. The presiding justice in the case attended the fight, invoked the monarch’s name, and followed a specific ritual that called for God to intervene and bring victory to whichever side was honest in its claim. Given the time period, the champions likely fought in a makeshift arena. But later trials by combat in England took place in special arenas (“the lists”) with stands for spectators.

Although the Abbot of Meaux paid better, his champion fought poorly. Once defeat became a possibility, representatives of the feuding abbots came to terms.

Game of Thrones has made this odd aspect of history famous, as trials by combat feature prominently in the fate of two characters. Its counterpart is the trial by ordeal, in which someone accused of a crime is, say, burned with a hot iron, and God is called upon to protect him from harm if he is innocent. Most people know this idea thanks to a scene from Monty Python and the Holy Grail, in which commoners debate whether to burn a woman to figure out if she’s a witch.

Practices like these have existed for thousands of years, and they persist in certain parts of the world. For those who study them, their longevity makes it hard to believe that they are only superstition-fueled absurdities. Academics have long debated what purpose they served, and some have come to the surprising conclusion that they weren’t such bad ideas.

Judging suspects by calling on God to perform miracles may have even worked.

A Trial of Fire and Water

Between the Game of Thrones and Monty Python scenarios, the situation in which a single suspect faced divine judgment was much more common.

The diversity of ordeals inflicted by judges and communities on suspected wrongdoers is as variable as man’s imagination. In medieval Europe, suspected criminals grasped hot iron or were dunked in ponds. In an example from the Bible, a priest tested a woman accused of adultery by giving her “bitter water” that would supposedly impact innocent and guilty women differently. In India, one ordeal practiced in the 1800s involved weighing a man on giant scales that held a large quantity of clay. In Liberia, human rights groups have highlighted the current practice of burning suspects with a machete. In each case, this was not the punishment for the crime, but the trial.

Giving people poison, condemning people who float in water, and expecting God to keep hot iron from burning innocents… it sounds like superstitious slaughter. Yet it was often a thoughtful process.

In medieval Europe, for example, the primary way for courts (or villagers who didn’t have lawyers and a formal process) to respond to an accusation was by asking the suspect, witnesses, or people who knew the suspect to swear oaths to his or her guilt or innocence. (These oaths invoked God and called for the performance of a long, detailed ritual—a process some scholars compare to taking a polygraph.) They resorted to ordeals only when oathtakers contradicted each other, when the suspect was seen as untrustworthy, or when oaths were otherwise unreliable. (Perhaps because the crime was supernatural, meaning no one could witness it.)

Essentially, people asked God to render judgment only when they could not themselves.

Scholars have pointed out that belief in “immanent justice” was common, that appealing to the divine imbued rulings with more authority, and that small communities may not have been able to afford the uncertainty of letting a likely criminal go free due to lack of evidence. Perhaps this is why Europeans so often settled disputes by asking God to perform miracles?

But even when people did turn to ordeals, it was rarely a death sentence. Surprisingly, the accounts and data we have from Europe demonstrate that most people who endured trials by ordeal were found innocent.

How could this be? How were so many people vindicated by a process that considered them guilty if a hot iron burned them?

At least in Europe, the suspected answer is that priests manipulated the results. Ordeals were days-long affairs that followed strict rituals, but as noted by economist Peter Leeson, those instructions gave priests leeway. An injury from a hot iron might be bandaged up and investigated by a priest three days later to see if God had healed it. (A very subjective judgement.) Priests and judges also rarely sent women to trials by water. This is likely because women’s (on average) higher body fat percentage makes them more buoyant than men, and floating in the trials indicated guilt.

Priests may have manipulated the results because they wanted ordeals to be punishments for people who were unprovably guilty. Or it could have been a merciful punishment, especially in the case of unjust laws. When fifty men who had hunted King William Rufus’s deer all passed a trial by ordeal, he reportedly yelled, “What is this? God a just judge? Perish the man who after this believes so.”

Leeson’s theory, however, is that priests successfully used ordeals to determine who was guilty. Among a devout population, only innocent people would ask to prove their innocence through an ordeal, which explains why priests usually “interpreted” the results in a way that found people innocent.

If every ordeal ended with a miracle, of course, people would turn skeptical. And atheists presented a problem. The key, Leeson suggests, would be for priests to (consciously or unconsciously) condemn the right number of people. If too many people choose a trial by ordeal, that’s a sign that the flock has grown skeptical; the priest should condemn more people to re-instill the fear of God and deter unbelievers. One analysis of European ordeals found that 63% of suspects were found innocent. Perhaps that’s the right ratio.

The lengthy religious rituals of an ordeal also gave priests ample time to scare skeptics and identify unbelievers. Pre-ordeal, suspects spent three days living like a monk and were “liberally doused with holy water and transformed by long prayers of benediction into a prototype of the ancient righteous man delivered in times of tribulation.” On the day of the ceremony, priests made statements like “I adjure thee by the living God that thou shalt show thyself pure” and reminded people that God “didst liberate the three youths from the fiery furnace and didst free Susanna from the false charge.” It must have been a convincing show.

If ordeals seem like an irredeemably imprecise way to identify criminals, it’s worth considering the accuracy of the current justice system: One team of lawyers and researchers found that four percent of American death row inmates between 1973 and 2004 were wrongly convicted .

For Honor, Property, and Credit

The use of ordeals reached its European peak in the years from roughly 800 to 1300. Ordeals were a Christianized, pagan tradition, and critical clergy finally succeeded in removing the Church’s support for the practice in 1215. (They argued that it “tempted” God to demand miracles.) Absent the Church’s authority, ordeals slowly lost their legitimacy and were replaced by jury trials.

Academics generally link the decline of ordeals to the spread of literacy, science, and rationalism. Those with a more economic bent, however, suggest that ordeals went away once states had the resources and power to support jury trials that considered evidence. Ordeals were a “tribal tradition,” scholar Richard W. Lariviere writes, which disappeared “with the formation of communes—self-governing towns and villages—whose city charters were largely based on a revival of Roman law.” Before areas had enough wealth to support a professional judiciary and strong governments that could enforce laws, the ordeal was often the best legal tool available.

We see this as well with trials by combat.

Trials by combat (duellums) were less common than ordeals, but their rise and fall was similar in Europe. These literal legal fights mainly resolved property disputes: he-said-she-said cases where a judge or local authority could not resolve two people’s disagreement.

Unlike ordeals, scholars can’t redeem trials by combat with theories of how they discovered the truth. In theory, God helped the honest party win the fight. In practice, the strongest person, or the person with the money to hire the strongest champion, won the case. (In yet another example of history failing to live up to our romanticization of it, trials by combat usually ended with one of the fighters surrendering, and judges often had champions use weaker weapons like clubs to keep the trials non-lethal.)

Yet Leeson theorizes that trials by combat played a useful role—one that only economists can appreciate.

In feudal Europe, it was difficult to buy and sell land. In England, the monarch held all the land and gave land rights to lords who gave rights to their land to lesser figures. The number of people with an interest in one piece of land made it hard to sell.

When someone disputed the right to a property, a trial by combat created a novel situation: the person willing to spend the most money got the land. That person could spend more money on a champion, or hire all the available champions, and win the dispute. From the perspective of an economist, who thinks it’s terribly inefficient for someone who values the property less to control it, that’s the best possible outcome of an intractable dispute.

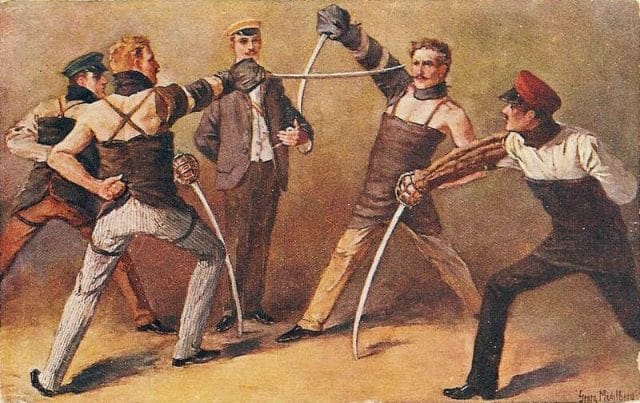

Duels outside the legal system, however, were much more common. The duels that remain so famous date back to the Italian Renaissance. Its inventors, in creating formal rules for fighting to resolve a dispute, intended to prevent endless conflicts and generation-spanning vendettas. The rules were designed to limit the advantage held by good fighters—something made easier with the development of dueling pistols, whose poor accuracy made winning a duel comparable to winning a coin toss. As journalist Arthur Krystal writes, “The duel of honor was supposed to cut back on unchecked violence… to make men think twice about resorting to violence.”

It didn’t work out. Dueling became a status symbol, like owning an iPhone. Sometimes duels were a pretentious show; Mark Twain once quipped that spectators at duels in France sat directly behind the duelists for their own safety. But when taken seriously, men died for honor. From 1589 to 1610 alone, around 6,000 Frenchman died. In the United States, journalists and Congressmen died dueling with regularity. We all know about Hamilton, but Abraham Lincoln accepted a dueling challenge that was averted at the last moment by his friend’s diplomacy. (Lincoln helped by suggestively waving around a saber with his long arms.)

This is why people often look back at dueling as a social convention run amok, with people dying over silly disagreements. (Imagine dueling when you and your friend argue about the latest Marvel movie.)

But like with ordeals, historians and economists looking for reason among the madness have some fascinating ideas. Economists Robert Wright and Christopher Kingston, for example, believe that the concept of honor in the American South was not a silly, nebulous concept but a specific economic one, and that dueling was an important, informal legal institution.

Understanding why begins with the recognition that plantation owners constantly borrowed money. After all, they invested huge sums to plant cash crops whose payday came once a season. At the same time, the courts and legal system had a limited ability to resolve disputes over debts. Being honorable meant being good for your debts and a man of your word: a prerequisite for business dealings.

So why duel? For one, because it was very public. Newspapers posted dueling challenges, and word spread quickly. In the absence of high-functioning courts, issuing a challenge offered someone who felt mistreated by a plantation owner or money lender a means of redress. It was a public challenge to their business reputation.

Accepting a challenge also offered an honest person (perhaps he failed to repay a debt due to a failed crop) a chance to prove his honesty. And since the formalities of challenging someone and naming seconds were time-consuming, they offered an opportunity to negotiate a compromise before a duel took place.

“The credit implications of [dueling challenges] were certainly negative,” write Kingston and Wright. “Seen in this light, duels take on a more rational cast.”

This doesn’t exactly redeem duels—the primary reason many duelists needed debt was to buy slaves. But it does demonstrate how a seemingly irrational practice actually played an important legal and economic role—and why the practice persists, like ordeals, in some areas with weak courts and governments.

***

With this understanding of duels and trials by ordeal, the season finale of Game of Thrones seems inevitable. (Spoilers ahead!)

In the show’s sixth season, King Tommen bans trials by combat, which means that his mother, Cersei, who is accused of incest, will face a trial at the hands of her rivals. She can no longer rely on her champion, a Frankenstein’s monster of a knight, to win her freedom.

But King Tommen rules over a feudal kingdom, and his rule relies on the loyalty of rival aristocrats and religious figures. He has too little power to enforce justice over his murderous subjects—the situation where the imperfect solutions of trials by duels and hot irons and calls for divine intervention thrived, because they at least offered a resolution in a world that couldn’t achieve justice. Facing the prospect of a trial she will lose, Cersei chooses to kill all her rivals and those who want to judge her.

In both our world and the fictional world of Game of Thrones, trials by combat and ordeal seem absurd, unjust superstitions. And they are. Yet in many ways, given the limitations of the time, they could offer the best path for resolving a dispute, despite the potential for abuse.

It’s a trite point, but worth considering: Many aspects of our legal system could seem equally absurd to historians hundreds of years from now.

Our next article investigates why we still haggle at car dealerships. To get notified when we post it → join our email list.

The cover image from Game of Thrones is by Macall B. Polay, HBO.

![]()

Want to write for Priceonomics? We are looking for freelance contributors.