The Oregon Public House, a Portland pub. Photo credit: Rachel Hadiashar.

Everyone has an excuse to buy one more round of drinks, but here’s a new one: It’s for charity.

The Oregon Public House bills itself as “the world’s first non-profit pub.” Patrons approaching the Portland pub pass a sign that reads “Have a Pint, Change the World.” The pub has 3 menus, one for food, one for beer, and one for local charities that receive 100% of the bar’s profits. Diners and imbibers get to choose which charity they want to receive the surplus from their bill.

The pub has raised over $15,000 for charity since it opened its doors last May, and it will donate more once it’s better established. According to Ryan Saari, founder of the Oregon Public House, the goal is to donate $10,000 a month — an aspiration that will call for business savvy as well as generosity. “We want to be the most profitable nonprofit,” he tells us.

A nonprofit bar may sound like an “only in Portland” phenomenon, but the Oregon Public House has peers in the Okra Charity Saloon in Houston, Shebeen in Melbourne, and, until recently, Cause in Washington DC.

Despite its nonprofit status, the Oregon Public House doesn’t enjoy much in the way of tax breaks and special privileges. And that’s the way its founders like it. “We are trying to set a model that doesn’t need special privileges,” says Saari. “We want to show that we can run a successful business but at the same time give back.”

The bar is an intensely local product of a city with a craft brewing craze and a state with a strong nonprofit sector. Yet it also aspires to further a global ambition — to marry commerce and charity, profits and good works. A nonprofit bar may sound like a punchline, but the people behind it are serious about showing that Adam Smith’s invisible hand can be a bit more generous.

Liquid Fundraising

A night of beer and wings at the Oregon Public House is not a sanctimonious experience. Other than its decision to be family friendly, the pub feels much like any other bar. “It’s just a fun place to have beer and connect with friends,” Saari tells us.

Board member Stephen Green adds:

“Many people come without knowing about our mission. We have 3 different signs: eat, drink, and give. And people are perplexed by the last one [until] we explain.”

But you don’t overhear many conversations about charity in your average watering hole. In Portland’s philanthropub, it’s a common occurrence as patrons decide which charity to donate the proceeds of their meal to. Both Green and Saari love when customers first learn that their order supports charity — that “Wow. Duh!” moment, as Green calls it, when people realize that they don’t have to choose between spending money on a night out or supporting charity. Saari explains:

“My favorite thing is sitting at the bar and having a drink and listening to people place an order and the bartender asks, ‘What charity do you want that to go to?’ And they say, ‘What?’ It’s amazing to see that spark as they find out what’s going on.”

That spark first came to Saari about 4 years ago at a barbecue.

For those wondering who runs the world’s first nonprofit bar, the answer is a team of volunteers led by the coolest pastor you know. Ryan Saari has worked on community outreach in schools, with the homeless, and for AIDS causes. He also is pastor of a church that The Oregonian describes as follows: “Indie music plays over speakers and pews are replaced by candlelit tables where patrons sip coffee during the sermon.”

As Saari sat in his backyard, barbecuing with friends, the group discussed how to get involved in the community. As Saari related to The Oregonian, they knew that Portland was saturated with nonprofits. But every nonprofit needed help fundraising. Saari suggested a pub.

Several years later, the pub is now a reality and it has the community aspect the friends imagined. Deciding which organization out of the rotating group of local nonprofits to donate to gets patrons talking about the local challenges those charities tackle: Friends of the Children partners vulnerable children with a professional mentor from kindergarten to high school graduation; My Voice Music gets youth involved in musical programs; Habitat for Humanity builds affordable housing. The charitable aspect also brings in a slightly wider clientele, as supporters of the nonprofits come in for meals. “We get some non pubgoers,” Saari tells us.

The pub has started functioning as the “fundraising department” for Portland’s nonprofits that Saari imagined. It donates all its monthly profits (or “surplus”) — about $1 of a $5 local beer is profit, while margins on food are smaller — and Saari hopes to start an in-house brewery. Different beers would each support a different cause. So, as the Times noted in an article on the pub, customers buying Oregon Public House Education Ale “would know the proceeds were going to an education charity supported by the pub.”

The few new philanthropubs like the Oregon Public House are a new model, distinct from Whole Foods donating 5% of its sales on 5% days or Toms donating a pair of shoes to a child in need with every purchase. Yet it’s also a democratized version of a staple of the fundraising playbook: the charity gala.

Whether it’s to raise funds for anti-trafficking programs, a local school, or the Met, $1,000 a plate galas raise millions of dollars each year for charitable causes. The per plate price is a donation. It’s often also the opportunity to mingle with celebrities, network with business associates, and enjoy high society — at a discount thanks to charitable tax deductions.

In a sense, the Oregon Public House is the middle class gala, allowing anyone to turn a night out into charity without the allure of celebrities and without nonprofits turning into entertainment companies for the night. And the government doesn’t even need to foot the bill: despite its nonprofit status, the Oregon Public House pays its taxes.

Photo credit: Rachel Hadiashar

A Profitable Nonprofit

The leadership of the Oregon Public House hopes that they will inspire others to copy their model. But they don’t recommend going the nonprofit route.

“We wanted the credibility that comes with nonprofit status,” Saari told us, noting that the pub’s books are publicly available so that customers can see that he and the other board members are in fact volunteers that don’t make a dime off the bar. “It’s a cynical society, and we wanted to be above reproach.”

The state of Oregon recognizes the bar as a nonprofit, but the IRS does not. Saari says that the federal government kept asking for precedence, and they kept responding that they were the first of their kind. He believes that the concern that the Oregon Public House would have an unfair advantage over other establishments sunk their application. A suggested donation model may have worked, but the board worried about people donating a dime for a beer. So they decided to pay all their taxes.

The result was a lot of extra paperwork that limits some of the business practices available to the pub (due to their state-recognized nonprofit status) without the tax advantages of national nonprofit status. “Just one of those things you learn,” Stephen Green reflects.

Yet the board wasn’t disappointed with the outcome.

The partial nonprofit status earns the bar a lot of trust, and the seeming incongruence of a “not for profit pub” attracted media attention from the New York Times, NPR, and The Colbert Report. (An irate Stephen Colbert warned that beer and charity don’t mix, and worried that he might wake up the next morning asking, “Ugh, who did I feed and clothe last night?”)

Nearby businesses and breweries are supporters of the Oregon Public House. “We buy a lot of our beer from them,” said Green. “We help make the area a destination.” That support may have been strained if the Oregon Public House entered the same business tax-free.

But the pub’s board is particularly pleased with their status because it gives them the opportunity to prove a model. To show that a business can survive and thrive with charitable giving as its mission. “We want to show that we can run a successful business but at the same time give back,” Saari told us. He enjoys the Oregon Public House’s community aspect, but he points out that businesses from t-shirt shops to tech giants could orient themselves around the goal of fundraising charitable ventures.

Because despite being a nonprofit, profitability is really the bar’s number one concern. The food industry has a notoriously high failure rate, and as Priceonomics has covered, even successful brewpubs spend years paying off the upfront costs of establishing a restaurant.

For this reason, while the staff is paid, the pub’s board draws no salaries. “Our goal is to donate $10K a month, and we need to be lean and mean to do so,” Saari told us. “Managers not drawing salary is way to do that.” Bottom line concerns also explain why it took so long for the pub to go from concept to reality. Instead of taking out loans, Saari and co. relied on donations. After three years of fundraising $100,000 and receiving around $150,000 in donated materials and labor, two other philanthropubs had opened before the Oregon Public House.

Not that it’s a problem for Saari, who is “excited for others to steal this model” and says “we don’t care if we’re the first or the coolest. We want to be the most profitable nonprofit and give over $100,000 a year to other nonprofits.” Thanks to their lean practices, there are encouraging signs. The Oregon Public House has donated over $15,000 to charity since they opened and earned at least one ranking as top brewpub in Portland.

Mixing Business with Idealism

The founders of the Oregon Public House want to be a model but don’t recommend applying for nonprofit status. So what do they suggest?

They advise applying for status as a benefit corporation — a legal status best understood through the cautionary tale of Ben & Jerry’s, the progressive ice cream company behind flavors like Chunky Monkey and Cherry Garcia.

Ben Cohen and Jerry Greenfield first opened an ice cream parlor in Burlington, Vermont, in 1978. Cohen had ageusia, a partial loss of taste, which led them to feature large chunks — of pretzels, fudge, cherries, and so on — in their ice cream. The chunks were a hit. Soon Ben & Jerry’s sold pints of its ice cream around the country.

As Ben & Jerry’s grew into a hundred million dollar business, Cohen and Greenfield — men often described as hippies who named one of their first flavors after Jerry Garcia of the Grateful Dead — were dissatisfied. Cohen griped that the company was “just a business, like all others, [that] exploits its workers and the community.”

In response, a friend challenged the two to create a company in their own image. One article on the company describes their reaction:

Over time, Cohen and Greenfield came to view their business as, in Cohen’s words, “an experiment to see if it was possible to use the tools of business to repair society.” At the end of each month, said Cohen, he and Greenfield would ask of themselves and the company: “How much have we improved the quality of life in the community? And how much profit is left over at the end of each month? If we haven’t contributed to both those objectives, we have failed.”

Cohen and Greenfield focused on the local economy by buying milk from Vermont farms, hiring Vermont artists for design work, and selling stock to Vermont residents. They limited the pay disparity between management and workers, considered environmental factors in their decisions, and committed 7.5% of pretax profits to charitable causes.

The company’s marketing moves included Ben and Jerry driving across the country to give out free ice cream from a cowmobile. (When the cowmobile burned up in an accident, Cohen described it as looking like “the world’s largest baked Alaska.”) When Congress entertained opening the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge to oil companies, the company protested by placing a 900 pound baked Alaska in front of the Capitol.

At the turn of the century, however, Ben & Jerry’s sales declined and its stock price along with it. Investors questioned its social mission and the company received offers from rival ice cream companies. In 2000, the Ben & Jerry’s board approved its sale to Unilever, a consumer goods multinational that seemed the antithesis of intensely local Ben & Jerry’s.

Less than a year earlier, Cohen had teamed up with investors to make an offer to buy the company, but Unilever offered more. Cohen, Greenfield, and the board all state that they reluctantly had to sell to Unilever. Greenfield said in an interview: “We were a public company, and the board of directors’ primary responsibility is the interest of the shareholders.” The board was legally responsible to take the better value and could only do its best to commit Unilever to preserving aspects of Ben & Jerry’s social mission during negotiations.

There is some doubt about whether the Ben & Jerry’s board was legally obligated to sell to Unilever. The idea that board members must maximize value for shareholders — in the form of profits — comes mainly from one court case and has been challenged in others. Moreover, one argument notes that courts generally defer to the judgment of boards unless there is a conflict of interest.

Still, as a benefit corporation white paper makes clear, the shareholder value idea is widespread, and the legal uncertainty makes directors nervous to prioritize a social mission, especially when shareholders with voting rights may not share an interest in anything besides profits. To simplify the case, the creation of benefit corporations is an answer to the Ben & Jerry’s dilemma.

The Oregon Public House could not apply to be a benefit corporation as Oregon did not pass legislation making it possible until recently. But now it would be the best choice. As Green told us while explaining why, uncapitalist actions like giving away profits is “in the DNA of benefit corporations.” They operate like a business, but unlike a regular for profit, benefit corporations’ employees, executives, and investors are all responsible for both making profits and performing a social mission. In other words, they are social entrepreneurs.

One of the first examples of a benefit corporation in the Bay Area is One Pacific Coast Bank. It is a socially responsible bank that does not, say, look to confusing, predatory fees as a profit center. It also focuses on loans to “transformative sectors” such as affordable housing, clean tech, and recycling ventures. All profits fund the One Pacific Coast Foundation’s programs in education and community development.

The number of benefit corporations is small, but as a movement it seems to have momentum. A leading law blog on social entrepreneurship estimated the total number of benefit corporations in the United States at 251 as of summer 2013. (The figure is uncertain as not every state records the number of benefit corporations.) Patagonia is probably the most well known. Nearly 1,000 companies worldwide are also certified as B Corps, a certification similar to Fair Trade meaning that a company meets standards of transparency and social and environmental responsibility.

Those modest numbers reflect that benefit corporation status is a recent invention. Maryland passed the first benefit corporation legislation in late 2010. Yet today, 19 states and the District of Columbia allow the creation of benefit corporations, while another 15 states have introduced legislation. Crucially, the estimate of 251 benefit corporations reflects the situation before Delaware, which is the legal home to some 60% of American companies, legislated benefit corporations.

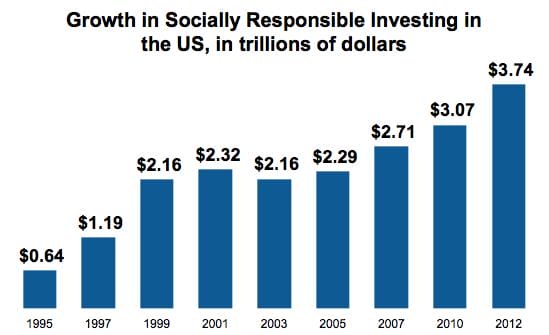

Momentum in the movement to marry commerce and ethics can also be seen in the growth of socially responsible investing. The catchall term for any attempt to invest in order to maximize financial return as well as social good includes strategies from refusing to invest in sin industries like smoking and gambling to focusing on socially and environmentally focused companies.

According to the Forum for Sustainable and Responsible Investment, “one out of every nine dollars under professional management in the United States is invested according to strategies of sustainable and responsible investing.” The growth rate of socially responsible investing, under their definition, can be seen below.

Data Source: Forum for Sustainable and Responsible Investment, 2012 report

Model Capitalists

Ryan Saari and Stephen Green have started talking to other Portland businesses about acting as a fundraiser for nonprofits. None have so far copied the Oregon Public House in donating 100% of their profits. Green talked with a furniture company, for example, that is considering donating a fixed percentage of profits from certain items.

These small businesses don’t have to wrangle with some of the thornier issues surrounding benefit corporations. Since they are self-owned, there are no questions about shareholder value or the correct form of incorporation. And the cut and dry practice of donating funds sidesteps charges of greenwashing or using a disingenuous commitment to a social cause as a marketing ploy. Reflecting on business owners who may be more interested in using charitable donations to draw in customers than to support the work of nonprofits, Green told us that “There’s definitely a cache, being in Portland,” but he believes that nonprofits will still appreciate the money regardless of the business owner’s intentions.

Photo credit: Rachel Hadiashar

Still, both Saari and Green are bullish on the prospect of business working for social causes and charitable giving. Describing businesses interested in donating proceeds to attract customers, Saari tells us, “They still want to do some good.” Green, meanwhile, cited the book Drive, in which writer Daniel Pink argues that people are less motivated by money than they are by the opportunity for “autonomy, mastery, and purpose.”

Green reflected that “a lot of the businesses [that we are working with] have a passion for what they do. And they need to make a living. But people do lots of things where there is no financial incentive.” He and Saari are chief examples, as they receive no compensation for serving on the pub’s board other than the satisfaction of being involved in their community.

A nonprofit bar seems very much the product of Portland’s cause conscious, craft brew loving, think local culture. The backers of the Oregon Public House, though, look forward to a time when mixing work, volunteerism, and social causes is the norm. Until then, people can at least raise money for Portland’s charities, pint by pint.

This post was written by Alex Mayyasi. Follow him on Twitter here or Google Plus. To get occasional notifications when we write blog posts, sign up for our email list.