Things were not going well for Taro Fukuyama and Sunny Tsang and their team during Y Combinator’s Winter 2012 batch. The team was accepted into the startup incubator as a dating site called Mieple. But the idea wasn’t getting traction with users, so they decided to pivot ideas just as they arrived in Mountain View for the start of the program.

During the first month of Y Combinator, Fukuyama and Tsang went through six pivots and evaluated seven different business ideas. First the dating website premised on introductions through friends. Then, a service for getting introductions to investors. Next, a service for introductions to jobs. After they got tired of “introduction-based” business ideas, they tried a few random ones: a translation company, advice about which movies to watch, a service to learn new skills like cooking by Skyping with an expert.

YC partners shot down many of the ideas, and the founders discovered the rest to be duds when they spoke to potential users. Toward the end of the first month, the team met with Paul Graham, the head of Y Combinator. He said they were currently the worst company in the batch and that they should take that as motivation to do better.

So they did better. The founders hit on their idea on the 7th try, one month into the three month incubator program. They founded AnyPerk, a startup that lets companies offer discounts and perks to their employees. The company now has 28 employees and makes serious recurring revenue every month. Two years after going through Y Combinator, they’ve jumped from the worst in the batch to near the top.

Hatching the Idea

The idea for AnyPerk came from perks that Y Combinator offers its own startups – discounts on business services. Y Combinator curates a list of discounts and freebies that companies offer to entice startups to use their services. These include AWS credits, free copies of MS office, or discounts on printing t-shirts.

Taro and Sunny, hailing from Japan, knew of several very successful companies in their home country that aggregated discounts this way and then charged employers a fee if they wanted to offer them to their employees. For employers, it was an inexpensive way to communicate to their workers “we like you.”

To test out the idea, the team took the list of YC discounts and asked a few potential customers, “Would you pay $5 for access to a list like this?” After receiving an enthusiastic response and at least some positive feedback from YC partners, AnyPerk was born.

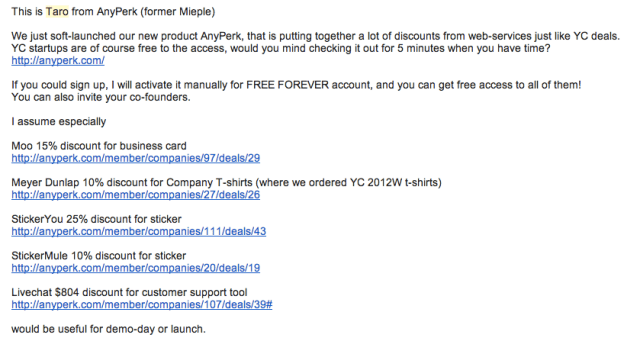

AnyPerk started by asking some of the companies that offered perks to YC if they’d be interested in also being featured on AnyPerk. This started seeding their marketplace of perks. Unfortunately, most of these perks were targeted at company founders, not employees. So they were things like discount business cards and stickers printing. Priceonomics was in the same YC batch as AnyPerk, so here is an email we dug up showing off some of their original perks from 2012:

Important stuff perhaps, but not something the average employee would care about. Without awesome perks, employers wouldn’t pony up dough for the service. However, without lots of employers on the service, it would be hard to attract companies willing to offer discounts.

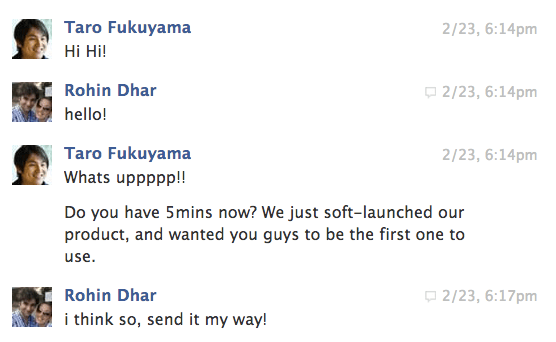

So, Fukuyama and Tsang decided to temporarily make the service free for employers to join so that AnyPerk could get some good discounts on the site. For the first year, AnyPerk was free for employers to join and the team worked hard to get discounts on their platform. Here’s the Facebook chat logs from when Priceonomics was recruited to join AnyPerk in February 2012:

Around the same time the two founded AnyPerk, another startup called BetterWorks was just winding down. This once hot startup had offered a similar employee-discounts service, but burned through $10.5 million in funding without getting much traction.

The demise of BetterWorks proved helpful to AnyPerk. First off, they learned from BetterWorks’ failed pricing model. BetterWorks wanted to insert itself in the the transaction between the employees and the companies offering the discounts (you buy the discounted service directly from BetterWorks, who then notifies the company selling the service). BetterWorks would make money by taking a percentage of the transaction, much like Groupon. The result was that it was a pain for companies to integrate with BetterWorks and they weren’t able to attract top tier discounts to their platform.

The other benefit was that when BetterWorks went out of business, their employees were available. Since AnyPerk needed someone to call companies to get discounts on its platform, they were able to hire the exact person in that role from BetterWorks.

For the next year, AnyPerk did two things. Get more discounts on their platform and let employers sign up for free. With lots of employers on board, they could attract better discounts that employees would care about. They started to amass discounts on things like cell phone plans, movie tickets, gym memberships, and actual perks that were great employee benefits.

By January 2013, the company had been around for a year and assembled some good perks on its platform, but it still wasn’t making any money. It was time to see if the business could successfully charge employers that wanted to offer discounts as an employee benefit.

AnyPerk added a simple pricing model. The cost for employers would be $5 per month per employee. A company of 10 people could get employees discounts on their phone bills and gym memberships for $50 a month. For a company of 100 people, it would be $500 a month.

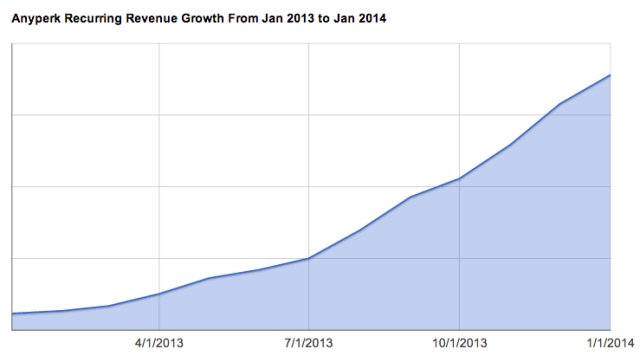

Lo and behold, it worked! Employers started paying to offer employee discounts. Below is AnyPerk’s revenue growth over the last year since it started charging for its service.

Obviously, this chart doesn’t have a Y-Axis label. (AnyPerk asked us not to share actual revenue numbers.) But it’s certainly “up and to the right.” Over this same time period, AnyPerk grew from 7 to 28 employees. You get the idea, they’re doing pretty well. Certainly well enough to say that Paul Graham’s kick in the pants worked as intended.

A Sales Driven Startup

The primary way AnyPerk grows is by hiring more sales people. These salespeople call employers and convince them to become customers of AnyPerk. Roughly 50% of customer leads come from inbound requests and the rest come from a sales person prospecting. When a new sales person joins the team, they’re not expected to make many sales. Over time they are expected meet a heavier quota.

Since they pay salespeople a salary and commission to make a sale, it costs quite a bit of money to acquire a customer. According to Taro, it takes Salesforce.com 18 months to break even on a sale because of the customer acquisition cost. In the case of AnyPerk, the company breaks even on a sale after 4-5 months.

What’s Next for AnyPerk?

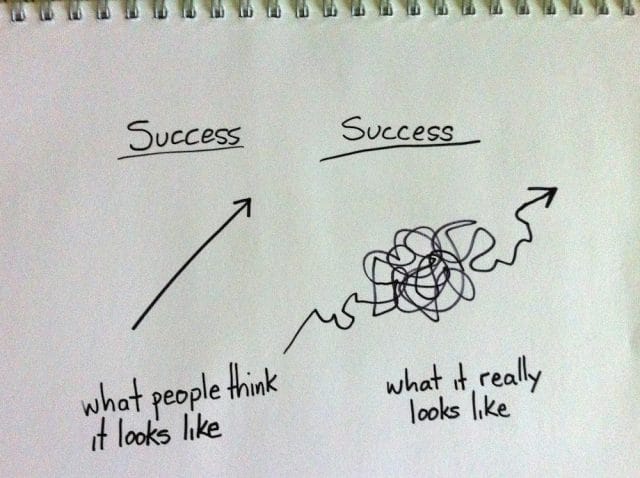

If you visit AnyPerk’s office, it’s a bustle of activity with 28 people crammed into a space meant for half as many. The company has its product-market fit and now it needs to keep doing what it’s been doing – acquire more customers and continue to improve the perks on its platform. To anyone looking in, it looks like a thriving startup. But like most startups that look successful on the surface, their path was anything but linear. There were ups and downs and wrong turns.

And even when you turn the corner on the darkest days, there is a still long way to go to building a large, successful company. AnyPerk has ambitions to dominate how employers make their employees feel valued. They’re starting to win business from large enterprises and to expand their software platform for administering more kinds of employee rewards. The company may have struggled in the beginning of their Y-Combinator experience, but now they’re near the top of the batch two years later. All it took was six pivots and relentless execution.

This post was written by Rohin Dhar. Follow him on Twitter or Google Plus. To get occasional notifications when we write blog posts, sign up for our email list.