“The car alarm is distinctive in its hellish medley of sounds; truly, it is the toy of Satan.”

![]()

Shortly after 10 p.m. on an August weeknight in 2005, a car alarm went off in Simi Valley, California. For nearly 45 minutes, the noise blared through the suburbs, catalyzing a symphony of barking dogs and hollering neighbors. For anyone within a mile-wide radius, the piercing, relentless, 100-decibel “WREE! WREE! WREE!” of a white Toyota Camry had foiled any chance at a good nights’ rest — and the car’s owner was nowhere to be seen.

As residents haplessly resigned to the siren’s incessance, 48-year-old David Owen Rye decided he’d heard enough. Clad in his nightwear, he stormed down the stairs of his apartment complex, looked the car right in its flashing headlights, drew his 9-millimeter pistol, and shot it point-blank three times.

While Rye’s action was criminal in nature (within minutes, he was arrested on vandalism and gross negligence charges), many branded him a local hero. Who among us hasn’t dreamed of pummeling the shit out of a car alarm? Perhaps no other audible device is so uniformly detested — and with good reason. Audible alarms are not only incredibly annoying, but almost entirely useless: they do not reduce crime or deter thieves, and they produce an overall net negative impact on society.

So, despite their utter uselessness, why the hell do car alarms still exist?

The Regrettable Origins of the Audible Car Alarm

First developed in 1913 by an imprisoned felon, the audible car alarm dates back to the mass production of automobiles in the early 20th century. A century-old issue of Popular Mechanics reveals that the earliest known car alarm wasn’t unlike that of today:

“The owner sets the alarm in operative position when he leaves the car. The device emits siren-like calls for help the moment the thieving “joy-rider” attempts to crank the car. The inventor believes the racket will fill the thief with terror, as well as attract attention.”

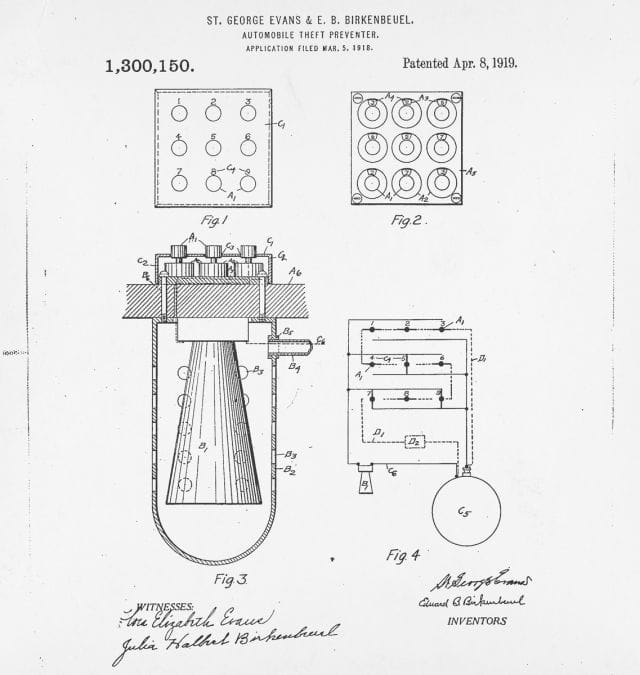

In 1918, two Portland men, St. George Evans and Edward Birkenbuel, filed the first patent for a fully-electric car alarm. Once triggered, the engine would lock and the alarm would persist until the car’s battery died.

The origins of hell: first patented car alarm, c.1918

Since these early days, a plethora of auto security options have come to market — but the old-fashioned car alarm has refused to die. While there are many different types of car alarms, the vast majority of modern cars are factory-fitted with what’s called a passive alarm— a God-forsaken device that activates automatically once a driver shuts off the ignition and locks the doors.

At a very basic level, these car alarms can be broken down into three components: sensors, a siren, and a control unit. According to a car tech expert, these parts interact in a fairly straightforward manner:

“The sensors [which are motion, shock, and pressure activated] are connected to different parts of the vehicle, and they are designed to trip whenever a thief attempts to gain access. When one of the sensors is tripped, it sends a signal to the control unit. The control unit then activates the siren, which will call attention to the vehicle and may scare off the thief.”

Theoretically, the alarm’s motion and shock sensors exist to detect “jostling” in the car that would indicate a theft, but instead they’re set off by loud music, strong gusts of wind, and cats. Herein lies the first major fuck-up with car alarms: these sensors are often dialed to incredibly sensitive settings, and the vast majority of the time they’re triggered, it’s not a thief who’s at fault.

99% of Car Alarms Are Not Caused by Theft

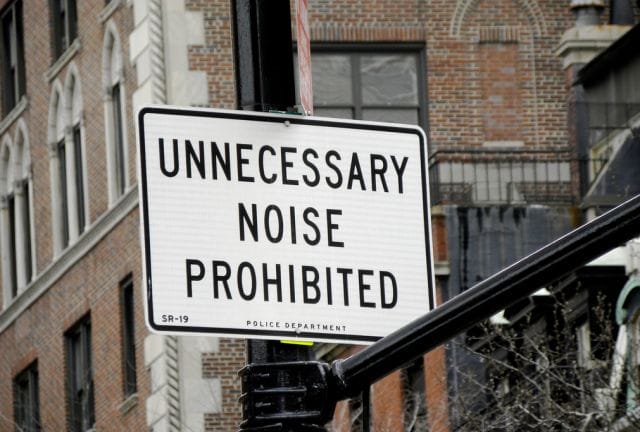

In study entitled “Rethinking the Regulation of Car Horn and Car Alarm Noise,” noise pollution researchers with the Columbia Journal of Environmental Law estimated that 95-99% of all car alarms in New York City were falsely set off — most commonly, by “vibrations of passing trucks, or glitches in the car’s electrical system.”

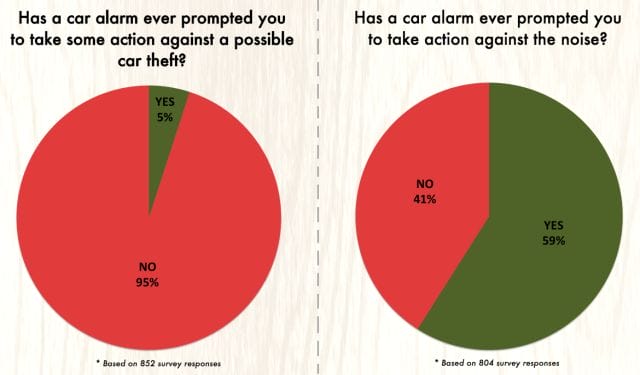

Car alarms go off in major cities so frequently that observers just assume they’re always accidental. A survey of New Yorkers by Transportation Alternatives found that a mere 5% of people who hear car alarms feel compelled to take action against a potential car theft, whereas 95% give no shits.

On the contrary, 59% of those surveyed admitted to reporting a car alarm to the authorities not as a potential theft, but as a noise complaint:

Zachary Crockett; data via TransAlt

A report filed by the Insurance Institute for Highway Safety (a nonprofit which seeks to reduce vehicle incidents) found false alarms to be so “ubiquitous” that even the owners of the sounding cars don’t take action. As a 1992 article in New York Magazine elaborates, thieves know this, and often take advantage of the fact:

“[A] guy was going down the street rocking parked cars back and forth. The rocking inevitably set a car alarm to wailing. The thief knew that nobody in the neighborhood would pay the slightest attention to a car alarm, so he used the noise to cover the sound of breaking the window. Then he stole the radio out of the car.”

In a roundabout, counteractive way, audible car alarms have actually made it easier for thieves to steal vehicles.

Thieves Know What They’re Doing

While some 99% of all car alarms are estimated to be false, rates of auto theft in the U.S. are quite high. In 2012 alone, the FBI’s Uniform Crime Reporting Program logged 721,053 stolen vehicles — a rate of 230 per 100,000 cars. Every 44 seconds, a car in stolen in America. The vast majority of these thefts (80%) are carried out by organized crime rings and experienced technicians — and for them, disabling audible car alarms is not a particularly challenging endeavor.

“The vast majority of alarms can be disabled in, literally, ten seconds,” a former New York City car alarm installer told TransAlt. “And a knowledgeable thief can take apart the most sophisticated $1,000 alarm installation in less than 5 minutes.”

Via Brett Jordan (Naga DDB Malaysia)

Whether the alarm is factory-installed by the car manufacturer, or an aftermarket product doesn’t make much of a difference. In a letter to the San Jose Mercury News, a tow truck driver brags about how effortlessly he can break into a vehicle and disable its alarm (or bypass it entirely):

“There isn’t a car I cannot unlock. If I want your car, I will unlock it, usually get it in neutral, and some I can even start without the keys or ever damaging the car in any way or the alarm ever making a peep. [When the alarm goes off], most aftermarket alarms are easy to override or completely disable in about 15 seconds. My customers and the cops are always amazed at the speed with which I am able to unlock a car and disable the security system…car alarms are pretty much useless.”

For petty thieves on foot, car break-ins are even easier: “Any car thief will just break a window if he wants the stuff in your car,” he adds, “and for him, the alarm actually covers up the sound of him breaking your glass.”

Calculating the Socio-Economic Costs of a Car Alarm

In 2003, after many sleepless, car alarm-filled nights, New York resident Aaron Friedman decided he’d had enough. “I started doing research about car alarms and discovered that they were totally useless in preventing car theft,” he told The New Yorker. “That’s when this really became, you know, a vendetta.”

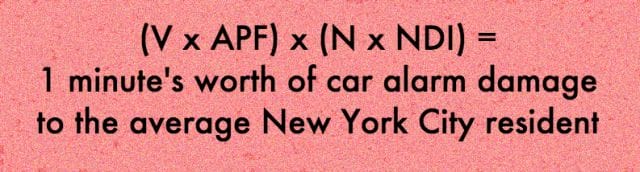

With anti-noise coalition TransAlt, he launched an all-out offensive on car alarms, claiming that that were not only useless, but posed financial and health-related burdens to those who had to regularly endure its cries. To demonstrate this claim, he culled a formula:

Via TransAlt (much more on the formula at this link)

Here, ‘V’ is the value of one minute of the average New Yorker’s time (calculated using average per capita income figures); ‘APF,’ or Aggravation Persistence Factor, accounts for the damage that an alarm does above and beyond the time that it is actually sounding (cost of lot sleep, lowered productivity, etc.); ‘N’ is the alarm’s noise over and above the average street decibel level; and ‘NDI’, or Noise Depreciation Index,measures the degree to which additional noise in an environment degrades a city dweller’s quality of life.

“When a [person] buys and installs a car alarm, its price does not account for the health, productivity, property value, and quality of life costs the alarm will impose on the owner’s neighbors,” writes Friedman. “This model provides a simple, straightforward formula to allow us to begin to calculate the cost of audible car alarms in the dense urban environment of New York City.”

According the Friedman’s calculations, car alarms cost the average New Yorker between $100 and $120 per year in direct/indirect costs.

Via Rev Stan (Flickr)

Noise pollution, cites TransAlt, also poses health risks. A 1982 study by researchers in Stockholm found that loud noises (defined as anything over 95 dBA) “caused an increase in blood-pressure in healthy normotensive subjects as well as in patients with essential hypertension.” A variety of other studies on the relations of noise and public health have found correlations between alarms and “gastrointestinal illnesses, psychological problems and unhealthy fetal development.”

As many new car alarms exceed 125 decibels — louder than a rock concert at full-blast — this isn’t surprising.

Useless…Yet Abundant?

Today, audible, “passive” car alarms are but one of dozens of security options automakers have when outfitting their products.

Most commonly, the passive immobilizer — a system containing a key fob carried by the driver, and a base station mounted in the vehicle — has served as a more formidable alternative. The key has a computer chip in it that communicates with the engine, and without it, the only way to steal a car is to tow it.

Car retailers have seen significant success using immobilizers. When Ford integrated them into their new Mustang, theft rates declined by 77%, and insurance claims decreased threefold. Likewise, when Nissan factory installed the devices in their Maxima line, average reported theft losses plummeted from $14,148 to $5,429 per year.

Silent alarms, which alert the car’s owner of a disturbance but do not let the whole neighborhood know about it, have also become increasingly cheaper and more accessible — yet relatively few new cars offer them as a standard integration from the factory.

Despite this, the “old-fashioned” car alarm — the obnoxious one that moans like a tortured apparition in the night, and arouses our deepest, darkest, most primal hatred — is still the most common type of security system installed. And at least for the time being, this completely useless device continues to eat away at our souls one “WEE-uuuu” at a time.

![]()

This post was written by Zachary Crockett. You can follow him on Twitter here.

To get occasional notifications when we write blog posts, please sign up for our email list.