Summer blockbusters are a well-established page in the Hollywood playbook. The ads start during the Christmas movie rush, so that by the time summer arrives, everyone knows about the latest $100 million dollar, special effects and star laden action flick.

But until the mid 1970s, studios reserved their best films for winter and mostly released movies that they expected to flop during the summer. Summer was the graveyard for movies that turned out poorly.

Why didn’t Hollywood think to distribute their biggest pictures during the summer? Executives thought that people had better things to do with their time than sit in a dark room watching movies all summer. As the Financial Times writes:

Back then June, July and August were the movie industry’s low season. By day, everyone was on the beach; by night, eating, drinking, dancing and carrying on. Who wanted to go rectangle-eyed in the dark, watching movies? That was a winter thing.

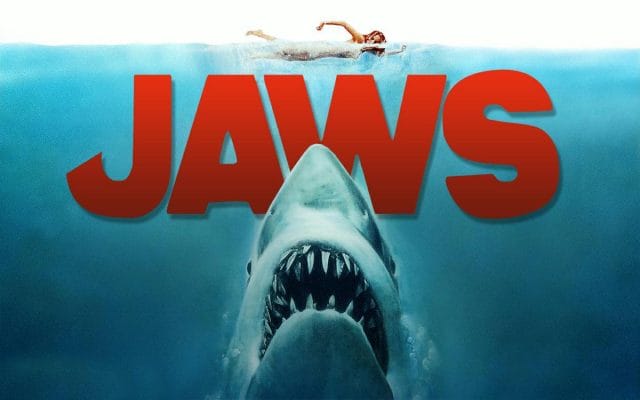

Jaws was the first film to challenge this conventional thinking. One reason for the then unorthodox timing? The Times also notes that the producer stated, “The release of the film was deliberately delayed till people were in the water off the summer beach resorts.” Director Steven Spielberg wanted the fear to be as real as possible, and that apparently included making sure that as many viewers as possible came from the beach to the film.

The film also broke with tradition in other ways. Rather than slowly roll the film out starting in big city theaters, the suits released Jaws simultaneously across the country. They also pioneered a huge marketing effort involving commercials, cross promotion with Jaws the novel, and merchandise tie-ins (perhaps more than have been seen since) such as ice cream flavors like “finnilla” and “sharkalate.” And, of course, once the movie was a hit, sequels.

Jaws became the highest-grossing movie of all time, surpassed two years later by Star Wars, which was also released in the summer. Like that, the summer blockbuster formula was born: a wide release, preceded by a huge marketing push, for a large budget film (rather than its commercial success, as had been previously been the case during a time when The Sound of Music was considered a blockbuster) that earned out its investment with merchandising and was followed by big budget sequels.

Amidst the summers spent on the beach and “drinking, dancing, and carrying on,” Americans would find time for a full lineup of Hollywood blockbusters from then on.

To get occasional notifications when we write blog posts, sign up for our email list.