![]()

The shopping cart leads a sad, under-appreciated existence.

He is pushed around. He is battered by cart collectors, and mauled by unattentive parking lot drivers. He is left for dead in dark alleyways, drowned in the sludgy tides of levees and bays. Occasionally, small children poop on him.

We take him for granted. After all, how would we pull off our Thanksgiving shopping, or buy a 16-pound bag of jumbo shrimp at Costco without the assistance of his sinewy, steel arms? How would we keep our children from wreaking havoc on the soup can aisle without his handy baby seat? More broadly, how would we — as over-consuming, gluttonous Americans — manage to carry our selections from the 44,000 items that typically line a supermarket shelf?

Few inventions have so profoundly shaped consumer habits. With the exception of the automobile, the shopping cart is the most commonly used “vehicle” in the world: some 25 million grace grocery stores across the U.S. alone. It has played a major role in enriching the forces of capitalism, increasing our buying output, and transforming the nature of the supermarket — and for its role, it has been dubbed the “greatest development in the history of merchandising.”

Rarely comes the time when we sit back and consider the history of the shopping cart. But gather, friends: that time has come.

Super(market)man

The late Sylvan Goldman; via the Oklahoma Historical Society

Born on November 15, 1898 in the small town of Ardmore, Oklahoma, Sylvan Goldman was bred to be a grocery man.

His father, a Jewish immigrant from Latvia, worked at a dry goods store. Here, Goldman received a crash course in consumerism: in the days before widespread refrigeration, he spent his youth doling out dried beans, whole grains, and rolled oats. By his early teens, he’d learned the wants and needs of shoppers.

During World War I, Goldman was whisked away to France, where he served as a food provisioner for two years. Upon his return in 1919, he ventured to Breckenridge, Texas — a booming oil town — and, with his modest savings, opened a wholesale fruit store. When the oil ran dry, Goldman mosied to California. Here, in the sun-bleached hills of the central coast, the 21 year-old entrepreneur had something of an epiphany.

At the time, most grocery stores in the United States were a hand-holding experience. Every item was behind a counter, and you’d be “waited on” by a clerk in a white apron. If you were buying, say, a pound of sorghum wheat, you’d point to it, then the employee would reach up, measure it out for you, and give it to you in a pretty package. From a shop owner’s perspective, this business model was not ideal: it required a large, knowledgable staff, and it moved goods at a rather slow pace.

Goldman had long-since recognized these shortcomings — and in California he saw an answer: the “self-serve” supermarket.

As early as 1916, stores had experimented with a self-serve model, where goods were put out on shelves and customers helped themselves. By 1919, this concept was in full swing in California, and Goldman, an impressionable young lad, was determined to take it back to Oklahoma.

Humpty Dumpty: one of the grocery chains aquired by Goldman; via the Oklahoma Historical Society

In January of 1920, Goldman returned to his home state with a promising offer from his uncles: they’d front him all of the necessary funds to open a supermarket, and give him 75% of all resulting profits.

By April, Goldman opened Sun Grocery Company, the state’s first “supermarket,” a massive complex that featured “all different types of food” and a self-service policy. The franchise was wildly popular and experienced miraculous growth: within three years, Goldman was operating 55 stores throughout Tulsa.

Just months before the Stock Market Crash of 1929, Goldman sold his stores to Skaggs-Safeway, a major, nation-wide grocery retailer. In 1934, with his new fortune in hand, he purchased Humpty-Dumpty and Piggly-Wiggly, two ailing food store chains in Oklahoma City. While America toiled in the post-depression years, Goldman remained upbeat: “The wonderful thing about food is that everyone uses it,” he told a reporter, “and they only use it once.”

But the grocer’s can-do attitude was no match for a shit economy: his stores began to stagnate in sales, and, for the first time, he risked going out of business. Just when he thought all was lost, he looked at a folding chair and saw a brighter future.

How a Folding Chair Became the First Shopping Cart

Zachary Crockett, Priceonomics

By the late 1930s, major changes were happening in the way that food was consumed: Freon, synthesized in 1930, led to the spread of the commercial refrigerator (by the late 1930s, more than 50% of Americans had one in their home). At the same time, preservatives increased the number of canned goods in grocery stores. As a result, consumers were not only buying more food per shopping trip, but bulkier, heavier items.

There was one big problem with this: at the time, self-serve grocery stores (including Goldman’s) only provided small wire-woven baskets to put groceries in. “When the housewife got her basket full, it was too heavy for her to carry and she stopped shopping,” Goldman recalled in a 1970 interview. “I thought if there was some way we could give the customer two baskets to shop with and still have one hand free to shop, we could do considerably more business.”

Goldman came to the realization that “[his] problem as an entrepreneur was no different than the problem [his] customers faced while shopping”: in order to sell more food, he’d have to figure out a way for his customers to carry less food.

At first, the solution didn’t come so easily. “When a clerk would see a customer’s basket practically full, he would hand them another basket and tell them they could find their first basket by the checkout stand,” wrote Goldman — but this required clerks who were constantly alert, and it wasn’t exactly scalable. Next, he considered re-arranging the goods into an “M” shape, attaching baskets to a tiny, parallel railroad track, and having customers shuffle along in an assembly line as their carts moved automatically. This proved to be a bit too complex.

Mulling around in his office late one night, Goldman inadvertently locked eyes with a folding chair. An Earth-shattering idea took hold: “What if one chair was placed on top of another? What if a basket was placed on top of each seat? What if it had wheels?”

Goldman leapt from his desk, grabbed a few folding chairs, two wire baskets, and some wheels, then ran through the back corridor to the shop of Fred Young, the grocery store’s handyman. For several hours, the two men tinkered with this “kit of parts”, eventually creating shopping cart v1.0.

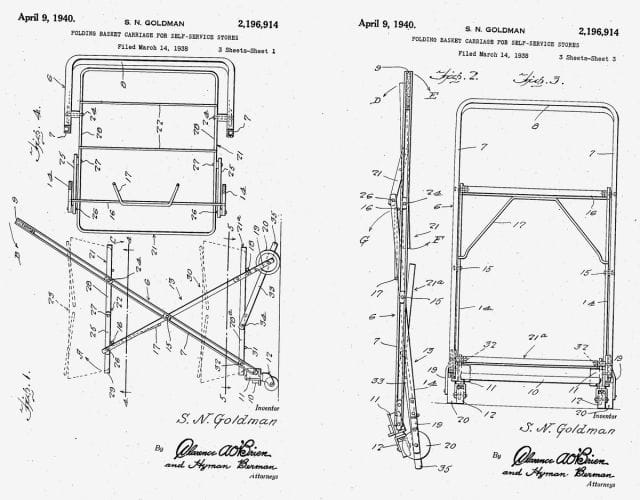

Sylvan Goldman’s original patents, filed in 1938; images via Google Patents

When Goldman tested his contraption on the street with a full load of groceries, the wooden legs of the chair snapped under the weight. Using a metal chair, he built a new one — this time with several improvements: two baskets were mounted on the cart on top of one another; when not in use, they could be removed and “nested” (stacked up), and the cart could be folded up to save space.

Goldman was thrilled. Not only did his device presumably double a shopper’s buying capacity, but it made the whole experience less straining for them: no longer would women have to haul 15-20 pound baskets around his stores.

But the inventor’s excitement was not equaled by his customers.

From Big Flop to Grocery Store Staple

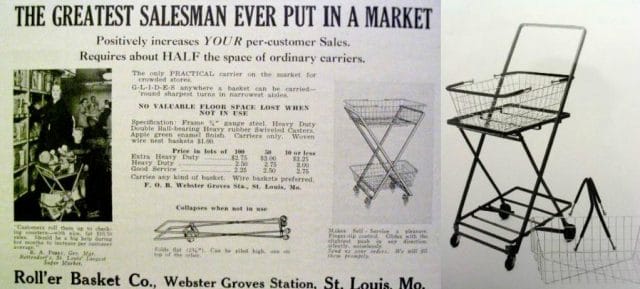

An early shopping cart ad (l), and one of Goldman’s carts (r); c. late 1930s; via the State Historical Society of Missouri

On June 4, 1936, Goldman constructed a dozen of these rudimentary carts and placed them by the entryway of his Piggly Wiggly stores.

He envisioned smiling faces, pats on the back, and cries of joy from happy shoppers; instead, they were utterly nonplussed. Years later, he recalled this moment of disappointment in a letter to the Smithsonian Institution:

“I went into our largest store, there wasn’t a soul using a basket carrier…Most of the housewives decided, ‘No more carts for me. I have been pushing enough baby carriages. I don’t want to push anymore.’ The men [said], ‘You mean with my big strong arms I can’t carry a darn little basket like that?’ And he wouldn’t touch it. It was a complete flop.”

Independently of Goldman, several other inventors had toyed around with the idea of a shopping cart throughout the 1930s, including Missouri-based Roll’er Basket Company. Unbeknownst to him, all of these efforts had failed. Determined to revolutionize shopping, the 39 year-old inventor set out to shift public opinion.

A voracious promoter, he first ran a series of local newspaper advertisements. “It’s new – It’s sensational. No more baskets to carry!” read one, with an accompanying image of a woman laboriously toting a food-stuffed basket. “Can you imagine,” beckoned another, “winding your way through a spacious food market without having to carry a cumbersome shopping basket on your arm?”

When this didn’t work, Goldman turned to an age-old marketing trick: he hired an “attractive girl” to stand by the front of the store, offering the carts to shoppers as they walked in. Still, this did little to garner interest. The shopping cart — or the “Folding Basket Carrier,” as he called it — just wasn’t sexy enough.

Actors hired by Goldman pose with his carts in one of his stores; via the Oklahoma Historical Society

Finally, Goldman enlisted his own employees (and hired a team of actors — both men and women) to push the carts through his stores with beaming smiles, picking items off shelves with ease. Before long, herd mentality took hold: shoppers gradually began to accept and cherish the cart.

Once his stores were thriving with merry cart-pushers, Goldman filmed his success and showed it to other grocers. Soon, the carts were in high demand: Goldman sold them for $7 each, and quickly amassed a two year backorder. To fulfil this demand, he licensed his newly-patented design to manufacturing outposts.

Ultimately, his grand plan worked: with increased carrying capacity (and aided by continued improvements in refrigeration and preservatives) shoppers drastically increased their purchases. His Piggly-Wiggly franchise thrived, and he amassed a fortune.

State of the Cart

Once made from steel, most modern iterations of the shopping cart are plastic; via Polycart (Flickr)

More than 75 years later, Sylvan Goldman’s original shopping cart has remained largely unchanged, with the exception of several considerable improvements.

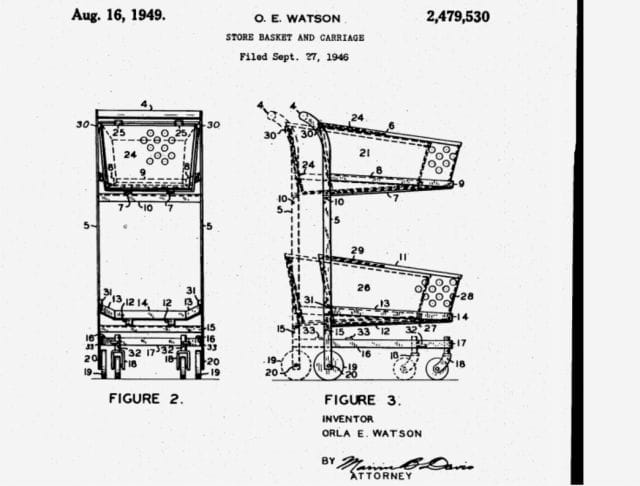

In 1946, Orla E. Watson, a World War I veteran turned machinist, designed a shopping cart with a “rear swinging door,” which allowed carts to be stacked into one another, thereby saving space. Much to Goldman’s chagrin, Watson’s company, Telescope Carts, Inc., became wildly successful.

When Watson introduced his cart, Goldman immediately countered with his own telescopic design — one that was not only $3 per cart cheaper than Watson’s, but more widely distributed (Goldman, wealthy by this point, had infinitely more resources than the new kid on the block). “It is unfortunate that there is always someone to spoil one’s fun,” Watson wrote in 1947.

Eventually, a legal battle ensued which ended in Goldman exchanging $1 for the exclusive rights to sell telescopic carts (he essentially lawyered his way to victory, and screwed over Watson). This telescopic cart would become the basis for all subsequent carts.

Orla Watson’s “swinging rear door” cart; via Google Patents

For the next 15 years or so, Goldman had a stronghold on the shopping cart market. In 1961, he sold off his company and embarked on a late-life career as a real estate developer. By the time of his death in 1984, he’d amassed a $400 million fortune.

His cart company, renamed “Unarco,” still operates today, under joint ownership of the Marmon Group and Berkshire Hathaway. Once $7, a modern Unarco cart now runs around $150; barring theft (which is a big problem), it lasts about 10 years.

Ten years after Goldman’s passing, his creation was rendered as a digital icon; since, it has become the definitive symbol of online consumerism, gracing the pages of thousands of ecommerce websites across the Internet.

At one time rejected as a nuisance, the shopping cart is seen as a necessity by today’s shoppers — so much so, that some analysts have attributed the demise of Sears and J.C. Penny to the stores’ “cartless” policy.

For grocery stores, they remain integral to the bottom line: studies have shown that larger carts lead to as much as 40% more purchasing. As a result, the carts of many retailers — including Whole Foods, Safeway, and Walmart — have doubled in size in the past 20 years, to as much as 15,000 cubic inches.

“Bigger capacity carts sell more groceries: today’s shopper wants to buy more,” wrote one cart manufacturer. “Impulse buying is the very essence of success in supermarketing…and it should not be restricted by limited capacity carts.”

Surely, Sylvan Goldman would be proud.

![]()

In our next post, we take a look at which professions have the longest commutes. To get notified when we post it → join our email list.

This post was written by Zachary Crockett. You can follow him on Twitter at @zzcrockett