![]()

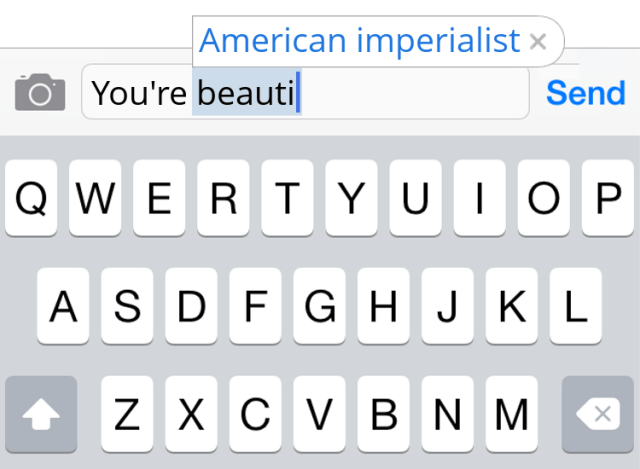

If you use a search engine, or any kind of cell phone you’re probably intimately acquainted with the magical mixed blessing that is predictive text technology. When you’re trying to sound out the correct spelling of an unfamiliar word, it magically appears at your fingertips, as if to say, “You were right in 3rd grade, learning to spell is pointless!” When you can’t remember the fact you wanted to look up, never fear! Just guess at the first few characters in the Google search bar and the answer might appear at the top of a drop down menu, as if to say, “Hell, remembering anything is pointless!”

Autocomplete is an example of predictive text. Autocomplete and its closely-related cousin, autocorrect, are what make it possible for us to mash out mostly-comprehensible English with our thumbs on touch-screen representations of keyboards, without any haptic feedback, and ‘keys’ smaller than raisins. With the aid of complex linguistic databases, linking probable combinations of characters and words together, they contextualize your thumby fumbling and interpret it into prose. These networks are rearranged and re-weighted according to the user’s feedback. As a user rejects, overrides, or accepts a phone’s corrections and completions, the user’s linguistic idiosyncrasies become part of the phone’s software (for better or for worse.)

Most of us usually take it for granted that our machines can complete our sentences better than our loved ones can. When you stop to think about it, it may seem like a uniquely digital phenomenon — only possible and practicable in the age of sophisticated computing technology, personal enough to monitor and learn from our every finger-stroke. That’s how it worked out for Western writing technology, which didn’t really see the widespread use of predictive text until cellphones made it a practical necessity (remember trying to text using a dumb phone keypad and no T9?)

Stanford historian Thomas Mullaney discovered that Chinese writing technology was way ahead of the game on this one: in the 1950s they built a precursor to predictive text into their typewriters. If a typist typed the character “mei”, the characters “li” and “di” would be extra-handy, to afford the typing of two common words in Maoist-era China: meili, meaning “beautiful”; and Meidi, meaning “American imperialist.”

Written Chinese is Very Complicated

As you may be aware, written Chinese is not based on a phonetic alphabet. Instead it’s composed of characters, some of which are composed of visual representations of objects or ideas. Each character corresponds to a spoken syllable, but its components might offer clues to its meaning or pronunciation.

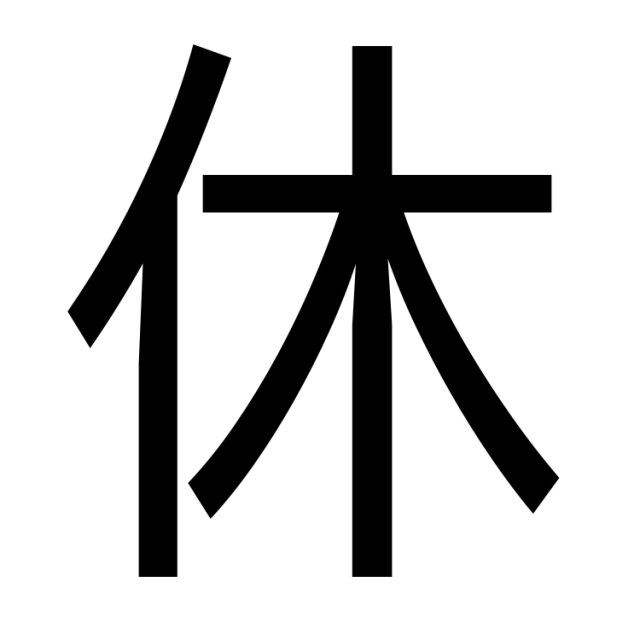

For example, the character 休 means “rest”:

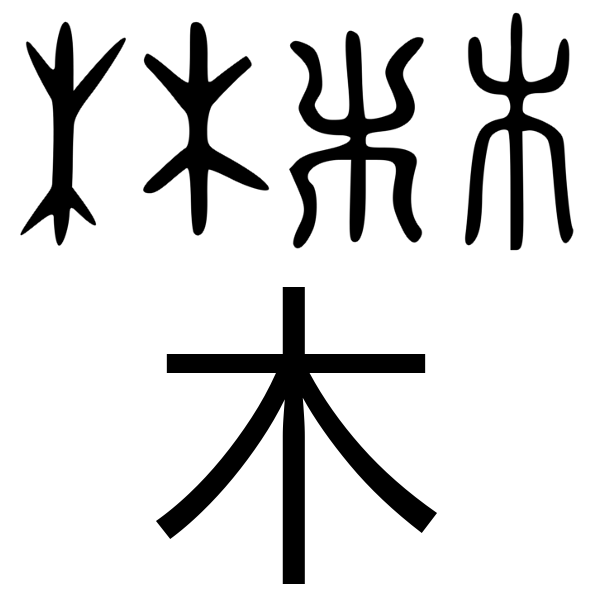

It is composed of two parts derived from pictograms. The left component of the character, 亻, is derived from the character 人 which means “man.” The right component of the character is the character 木, which means “tree.” So, the character for rest depicts a man resting beside a tree.

Etymology of the character 木, meaning “tree”, from oracle bone script through later ancient texts

This writing system was shared by several different languages and dialects throughout China’s history: Cantonese speakers and Mandarin speakers alike still attach the same semantic meaning to many of these symbols, even though they pronounce them radically differently. 休 — the character for “rest” — is pronounced xiū in Mandarin, and jau in Cantonese. This shared writing system is what made large Chinese empires possible, and has a lot to do with why China is a unified country today.

On the other hand, the writing system requires basically as many characters as the language has syllables, which, it turns out, is a lot. Written Chinese has over 80,000 characters, but thankfully many of these are archaic and rarely used. It is estimated that full literacy requires knowing about 4000.

This vast and sprawling writing system has made writing, particularly mechanical writing, really really hard. Can you even imagine a functional typewriter with thousands of keys?

Chinese typewriters don’t have keys: they have a tray of slugs with characters on them, and a lever. A typist uses the lever to select a character, the machine picks the slug up, inks it, types with it, and replaces the slug in the tray. The big challenge for the typist is, of course, finding each character. The tray holds 2,450 slugs.

When the first Chinese typewriters were constructed, starting in 1911, the convention was to organize the characters in what’s called “radical-stroke order”. Many Chinese characters are composites of smaller symbols, and some of these component symbols appear frequently and are called radicals, (亻 in 休 above is a radical.) To organize Chinese characters in “radical-stroke order” means to organize group them according to their component radicals, then to order these groups according to the number of brush strokes that would be required to write the radical out by hand, then to order the characters within the groups by the number of brush strokes that would be required to write the whole character out by hand. This is still how Chinese dictionaries are organized.

Right now, anybody who’s ever had trouble navigating a QWERTY keyboard should take a moment to be grateful that they weren’t trying to type on a Chinese typewriter. It’d be like having to look every word you wanted to type up in the dictionary. There are 214 radicals in written Chinese, and they don’t always look the same between characters. Because “literacy” requires more than a thousand more characters than fit in the slug tray there’s no guarantee that the character the typist is squinting for is in the main tray, or needs to be swapped in. Because of this, trained Chinese typists could manage only about 20 to 30 characters (each corresponding to a single syllable) a minute with this system.

A Model Worker

Text: “The invincible thoughts of Mao Zedong illuminate the stages of revolutionary art!” Poster of Madame Mao reading Quotations from Chairman Mao Tse-Tung, (AKA: The Little Red Book)

Revolutions are fat times for revolutionary typists, or at least they were in 1950 China, according to Mullaney: “From the ’50s onward, China was in a state of more or less perpetual political campaigns. The burden for a lot of this fell on typists.”

One typist in particular lead the charge. His name was Zhang Jiying, and he lived in Kaifeng. A long-time typesetter, he clocked in a “respectable” 1,200 – 2,000 words per hour (or 20-33 words per minute) on the traditional typewriter. “Only a few short months after the formation of the People’s Republic [October, 1949],” Mullaney writes, “he experienced a reported surge of inspiration and began to engage in a sweeping, experimental reorganization of his character rack.”

Even before the revolution, radical-stroke order was so onerous that many typists dedicated a section of their tray to “special-usage” characters and character pairings: mostly place names. Zhang’s innovation was to reorganize his whole rack as a massive special-usage section, preparing 1-dimensional “chains” of characters tailored to what he was going to be writing about:

The theme at one point might be that of “materials on the worker’s movement,” thus prompting Zhang to prepare such compounds as “production” (shengchan), “experience” (jingyan), “labor” (laodong), and “record” (jilu); at other times, the topic might be a more temporally specific propaganda campaign, prompting Zhang to prepare terms and phrases like “Resist America, Aid Korea” (kang Mei yuan Chao), the Korean War–era mass-mobilization campaign.

This system nearly doubled Zhang’s productivity in a short amount of time: in 1951 the People’s Daily published an article titled, “Kaifeng Typesetter Zhang Jiying diligently improves typesetting method, establishes new record of 3000-plus characters per hour.” That’s about 50 characters a minute. In 1952 he went on to break his own record, on film, typing a record 4,778 characters in an hour — nearly 80 characters a minute. Zhang had more than doubled his productivity.

Networks of Characters

Zhang was the perfect revolutionary hero: industrious, dedicated, and iconoclastic (against the correct icons). The party publicized, disseminated, and built upon his methods and accomplishments. In 1953 the People’s Daily published an article on a “new typing method,” which extended Zhang’s principle of adjacency to the full 2-dimensional matrix of the tray:

By, “selecting one character as the core and then radiating outward from it,” the typist could populate the […] eight spaces around each character with as many related characters as possible. Owing to this multidimensionality, the typist could […] begin to experiment with both vertical and diagonal arrangements. This not only increased the number of multicharacter compounds and sequences one could pack into a given unit of space, but also made it possible to string these mini-regions together into ever-radiating associative networks.

When typing with this new, “radiating compounds” method, the process of typing a word or a sentence goes like this: find the initial character, look around it for the next one, or the next several. If you find use for a new character pairing, rearrange your tray to make that pairing convenient in the future. (This happened to the character 毛, meaning “hair” or “feather,” and pronounced mao in Mandarin. It is also the family name of political leader Mao Zedong, and quickly gained central placement in many keyboards.)

Now, the typewriter tray starts to look a lot like a 2-dimensional simplification of the data behind Google’s autocomplete drop-down, or iOS-8’s QuickType keyboard, or the word suggestions given by your “dumb“ phone’s T9 algorithm. When seeded with an initial character, technology makes it easy to write what is likely to come next.

The big difference, of course, is the trays might be “predictive,” but all the prediction was ultimately manually determined by the user. By the late 1980s, Chinese typewriters were sold with empty trays: typists were left to construct their associative networks entirely on their own. There is, however, evidence that they were very good at it evolving useful networks over time.

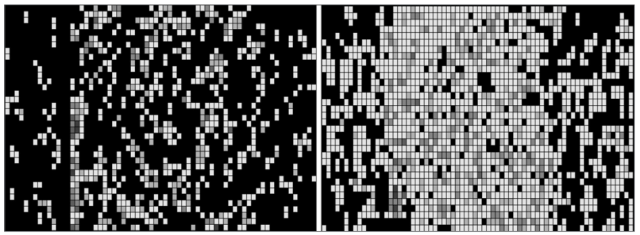

Take a look at these heat maps visualizing the trays from two Chinese typewriters. The one on the left is organized according to the pre-revolutionary radical-stroke order. The one on the right was used in UNESCO and dates from around the 1970s. Each slug is colored by “the number of adjacent characters with which [the character on the slug] can be combined to form a real, two-character word.” Black is 0, white is 8.

Chinese typewriter tray beds: organized in radical-stroke order on the left, and with a more “predictive” reorganization on the right. Source: Mullaney

Techno Linguistic Innovation

As it did most places, the Chinese typewriter eventually fell out of favor to computer word processor. “But,” Mullaney writes, “the computer was not the deus ex machina that ushered the Chinese language into an age of technological modernity.”

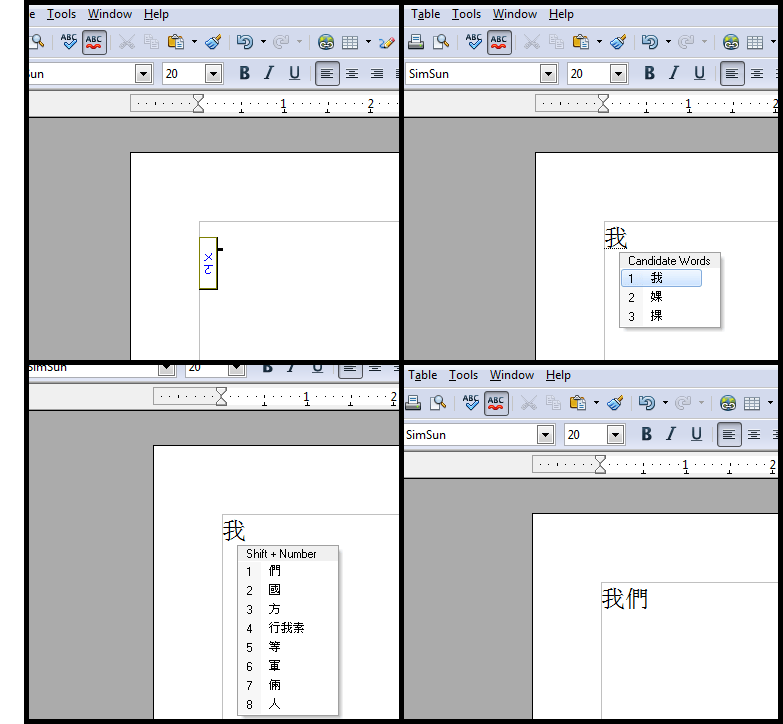

Mullaney’s theory is that these typewriters set a strong foundation for current Chinese text technology. To type in Chinese, on a Chinese computer, most people use a QWERTY keyboard. They start to write in Pinyin, a transliteration of phonetic Chinese into the Roman alphabet, and the word processor converts that into characters. The problem of course is there are many aspects of Chinese language that don’t fit into the Roman alphabet — there are only about 400 different possible Pinyin spellings for the tens of thousands of Chinese characters — and good word processors depend heavily on context. They suggest possible characters based on what you typed, with the most probable ones first: predictive text technology. “In this way,” a writer for Slate observes, “they function a bit like the text-editing software on most cell phones.”

How to type Chinese characters on a QWERTY keyboard

The second most common typing method is called Wubi — different kinds of stroke in Chinese characters correspond to different QWERTY keys. Wubi typists select the strokes that make up a character, in the order they would write them in were they writing the character by hand. This also requires disambiguation, as multiple characters can have the same stroke combinations, as they’re delineated on the keyboard. Again, predictive text comes to the rescue, suggesting possible characters as the user types.

“Predictive text isn’t widely used here beyond cell phones,” said Mullaney. “In China, it is the way you write.”

This post was written by Rosie Cima; you can follow her on Twitter here. To get occasional notifications when we write blog posts, please sign up for our email list