Cigarettes eat up the incomes of the poor.

In the United States, and nearly every other country, smoking is more common among the less wealthy and less educated. In the United States, 26.3% of people in poverty smoke compared to 15.2% for the rest of the population. College graduates are almost a third as likely to smoke as those who did not attend college. Because of this difference in smoking prevalence, Americans from the bottom third in household income spend nearly twenty times more on cigarettes as a proportion of their income than those from the top third.

In recent years, cigarette taxes have become the chief public policy instrument in the fight against smoking. Originally, the American government focused its efforts on warning labels and public awareness programs. But over the last several decades, state governments and the federal government have taxed cigarettes at ever higher rates.

Those taxes are paid disproportionately by people with low incomes.

Proponents of cigarette taxes argue that these taxes both get people to stop smoking and bring in public revenue. But some economists believe that recent hikes have had little impact on consumption. They suggest that the majority of people who were going to stop because of price hikes might have already done so. Still, state and federal governments persist in raising the level of taxes — generating ever more revenue from the poor.

Continuing to raise taxes on poor smokers, who are unwilling or unable to quit, may be ineffective and unjust.

A History of Tobacco Taxes

Taxing tobacco is nothing new.

Even before the harmful effects of tobacco were widely known, countries heavily taxed what Christopher Columbus called those “strange leaves”. Native to the Western Hemisphere, tobacco was first introduced to Europeans and Asians in the late fifteenth and sixteenth century.

Tobacco was almost immediately taxed, because it was seen as a luxury good. Putting an excise tax, an indirect tax on the sale of a certain good, on non-necessities like tobacco and alcohol has long been been viewed as a more palatable source of government revenue than alternative methods of taxation. Adam Smith, the father of modern economics, thought tobacco a “proper subject” of taxation for just this reason. The English and French began taxing tobacco in the 1600s.

The United States introduced the first federal tobacco tax in 1862 to help fund the Civil War. In 1883, tobacco taxes made up one third of the United States government’s tax revenue.

By the early 20th century, smoking cigarettes was the predominant method of tobacco intake — snuff and cigars had each once been more popular. In 1900, per capita cigarette consumption in the United States was 54 cigarettes. By the early 1960s, per capita consumption had reached over 4,000 cigarettes per year.

From The Atlantic

Despite the taxes on cigarettes — most of which came indirectly through taxation on tobacco — the rate of smoking grew tremendously through the first half of the 20th century. American soldiers in World War II were provided with cigarettes, and many came home addicted. Despite increased suspicions about adverse health effects, smoking’s popularity continued to crest, peaking in the decades after the war.

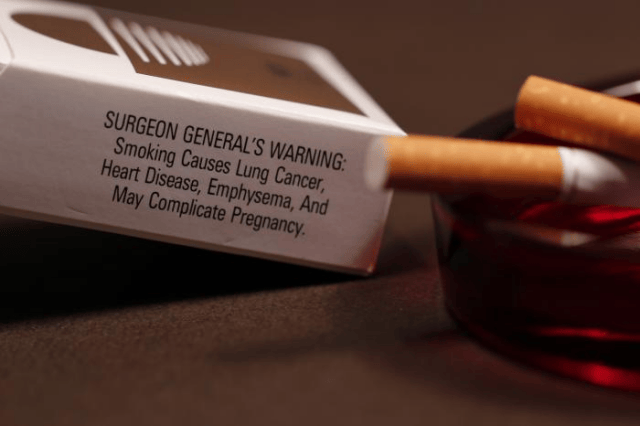

But by the early 1960s, the medical research linking cigarette smoking to cancer became overwhelming. A seminal moment in the history of tobacco regulation came in 1964, when the Surgeon General of the United States published a report linking smoking to lung cancer and heart disease. Many researchers consider the Surgeon General’s report on smoking to be the single most important public health moment in United States history.

Initially, the government focused efforts to deter smoking on public awareness campaigns and warning labels on the product. The locations where smokers could light up was also restricted. Raising taxes was not a primary weapon.

Public awareness was emphasized more than taxation at the beginning of the fight against cigarette smoking.

These interventions seem to have worked. In 1965, 42.4% of American adults smoked, but by 1990, only 25.5% smoked. In 2014, only 16.8% of Americans smoked. Similar reductions have been seen in many wealthy countries, though in some poorer countries, smoking prevalence is not declining as consistently.

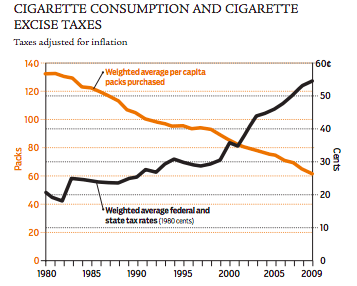

Over the last several decades, the U.S. government, among others, has increasingly turned to taxation to discourage smoking. Just in the last 25 years, that taxation has more than tripled in inflation adjusted dollars, from $0.73 cents in 1989 to $2.56 in 2014.

The chart below shows the price per pack for taxes since 1960 in 2014 dollars, as well as the amount that went to taxes. There was a massive jump in taxation levels in the 2000s, primarily driven by increases in tax rates by the states, and another jump in 2009 due to a $1.01 federal per pack hike.

Dan Kopf, Priceonomics; Data: Orzechowski and Walker

Taxing the Poor

Low-income Americans continue to smoke at an alarming rate. And thus, cigarette taxes are primarily paid by individuals with low-incomes.

Public Health researchers Kenneth Warner and Harold Pollack write in The Atlantic about the misconceptions of wealthier Americans about the state of the battle against smoking:

Among college-educated, upper-middle-income Americans, tobacco addiction is far from the epidemic it once was. Most of them don’t smoke, and neither do their friends. In those circles, the problem may seem to have been solved.

Smoking rates began declining in the United States in the mid 1960s. But the reduction among high income families has been more dramatic. From 1965 to 1999, smoking rates among individuals in high-income families went down by 62% in comparison to only 9% among low-income families.

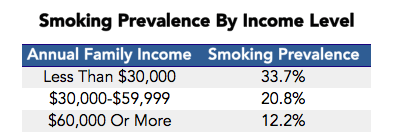

Matthew Farrelly, a researcher with RTI, a nonprofit research institute, researched smoking prevalence in 2012, and found that income is highly predictive of smoking:

Over one third of American adults from households with less than $30,000 in income smoke, and they are almost three times as likely to smoke than people from households with incomes over $60,000.

For smokers who make less than $30,000, cigarette costs represent more than 14% of their household’s income, compared to just 2% for the average smoker who makes over $60,000 a year. For the average smoker in New York from a low-income household, cigarettes account for nearly 24% of that household’s budget.

Increasing taxes on cigarettes has an outsized impact on the wallets of the poor. Does it also have an outsized benefit to their health?

The WHO and the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities argue that the regressivity of cigarette taxes is counteracted by higher responsiveness of poor people to those price changes. Defenders of increased taxes argue that the “health benefits of a higher tobacco tax are progressive.” More poor people stop smoking as a result of such taxes, and, as a group, their health outcomes are especially improved. One study on the impact of cigarette taxes in China suggests that if consumers respond to a price change by reducing cigarette consumption in the manner the researchers expect, the health impact of a tax increase would indeed be progressive.

But the progressivity or regressivity of these taxes is dependent on accurate predictions of consumer response to price changes. As we will discuss, for the United States and other countries, which have already raised prices a great deal, those projected responses may be inaccurate.

Farrelly hoped that his team’s research would lead to more discussion about the consequences of cigarette taxes on the poor, but has been disappointed. He believes there ought to be “a more comprehensive review of tobacco control programs” and a focus on policies that do not punish the poor.

To make these taxes more progressive, Farrelly feels that there is “a pretty obvious solution.” He says, “Earmark some of the funds and make sure they are used to support smoking cessation programs that are aimed at low-income smokers.” This is, surprisingly, rarely done.

American Taxes Versus the World

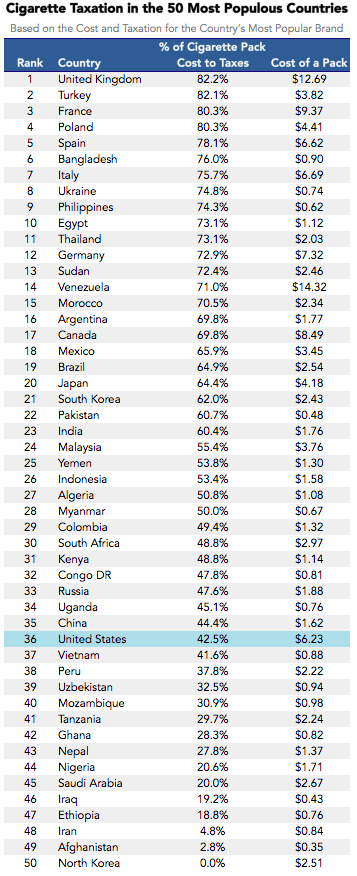

The United States is not unusual in heavily taxing cigarette consumption. Nearly every country in the world does so, though rates vary widely.

The World Health Organization (WHO) collects data on cigarette prices and taxation for the most popular brand of cigarettes across the world. Among the world’s fifty most populous countries, the United Kingdom is the world’s leading taxer of cigarettes. 82.2% of the cost of a pack is taxes. North Korea, where men are expected to smoke, does not tax cigarette consumption at all.

The following table displays the price of the most popular pack of cigarettes in the fifty most populous countries in the world—along with the percentage of that price that goes towards taxes. In the average country, taxes make up 51% of the cost of a pack.

Dan Kopf, Priceonomics; Data: WHO

The WHO advocates that governments set cigarette taxes so that 75% of the cost of a pack goes to taxes. The organization claims that “raising tobacco taxes to more than 75% of the retail price is among the most effective and cost-effective tobacco control interventions.” Only 7 of the 50 most populous countries in the world tax cigarettes at a rate of 75%, and there are ten that don’t even achieve 30%.

Yet it is not clear how the WHO reached its suggested minimum taxation rate. We could not locate any explanation, and when we contacted the WHO, we received no response.

For many countries, including the United States, raising taxes to reach such a level may not have the intended consequences.

How Price Sensitive Are Smokers?

The general consensus is that increasing cigarette prices through taxes greatly deters smoking. Despite their addictiveness, if people are forced to pay more for cigarettes, they are less likely to buy them. Nobel Prize winning economist Gary Becker and his colleagues demonstrated in the early 1990s that addicts are more responsive to price than might be expected.

Economists speak about price sensitivity in terms of elasticity. Elasticity refers to the percent decrease in the consumption of a product that results from the same percentage increase in the price. The elasticity of bananas, for example, is around -0.65, because a 1% increase in the price of a banana leads to a -0.65% decrease in consumption.

The WHO, Campaign for Tobacco Free Kids, and other advocates frequently cite research claiming that, on average, a 1% increase in the price of cigarettes leads to a 0.4% decrease in overall tobacco use in high-income countries, and 0.5% for low-income countries. About half of the reduction comes from people choosing not to smoke at all, and half from people choosing to smoke less.

Many studies find that the young and poor are particularly sensitive to price increases. The WHO reports that young people are more than twice as responsive as older adults, and the poor nearly double as sensitive as the rich. This makes intuitive sense. Young people are less likely to already be addicted to cigarettes and thus more likely to be deterred by high prices. And the poor may have less room in their budgets for the additional costs.

Yet the evidence these advocacy organizations use is primarily based on old research from a time when cigarettes were substantially less expensive. The elasticities that the WHO and others report are the same as those reported in the late 1990s. But is using these same elasticity numbers appropriate today for all countries?

The World Health Organization is a major proponent of increasing cigarette taxes.

In 2014, the economists Kevin Callison and Robert Kaestner published an article in the journal Economic Inquiry that challenged the consensus on the impact of cigarette taxes.

Callison and Kaestner assert that recent increases in cigarette taxes in the United States have not led to anything like the reductions that cigarette tax advocates promised. Rather, they find that these recent tax hikes have had a limited effect.

The researchers begin their argument by displaying a chart that juxtaposes the per capita consumption of cigarettes from 1980 to 2009 to the average tax on a pack. The chart (shown below) shows that regardless of where taxes increase, the downward trend in smoking persisted. During years when there is a large increase in taxes, there is not an equivalent drop in cigarette purchases.

The authors also conducted a more statistically rigorous analysis. Using data from the Current Population Survey, they examined whether states that passed large tax increases observed smoking reductions greater than those that did not. Using this methodology, they estimate that a 1% increase in price leads to, at best, a 0.07% decrease in consumption. Not even close to the 0.4-0.5% decrease frequently cited by advocates of taxation.

They sum up their argument in the following manner:

… our study suggests that future cigarette tax increases will have relatively few public health benefits, and the justification of future taxes should be based on the public finance aspects of cigarette taxes such as the regressiveness, volatility, and rate of revenue growth associated with those taxes.

Kaestner believes that the main reason for the difference between his findings and previous research is context. “The price is already very very high,” Kaestner says, “It’s a different pool of smokers.” Kaestner, who told us his research was not funded by the tobacco industry, suggests that higher taxation may lead to the reductions advocates predict in countries where prices are currently low.

Matthew Farrelly, who has also studied the issue, believes that elasticities have likely declined from 0.4%, but not as much as Callison and Kaestner estimate. “[Taxes] do decrease smoking,” he says. Farrelly’s research suggests that, currently, a 1% increase in taxes generally leads to a 0.25% reduction in consumption.

A “Win Win”?

Cigarette taxes generate substantial government revenues in the United States. In 2014, state governments received $16.5 billion, and the federal government took in $13.4 billion. Many of those federal dollars fund the State Children’s Health Insurance Plan (SCHIP), an initiative to assure American children have health coverage.

It is appealing for governments to believe that these taxes are a “win win”. The government can fund virtuous social projects and compel people to stop smoking. A WHO reports raves, “it costs little to implement and increases government revenues.”

From a different angle though, cigarette taxes look like a way to raise funds from a group with little political power. Cigarette smokers are less wealthy, less educated, and thus, less likely to vote. They are an easy target. Government attempts to raise taxes on other harmful products, like gas, is more politically difficult. “Big Tobacco”, which would have fought against these taxes for less scrupulous reasons, has seen its power dwindle substantially in the last several decades.

Some countries have taken this regressivity into consideration and implemented cigarette taxation in a way that is “pro-poor”. These countries raised taxes on relatively expensive brands, while lightly taxing the brands smoked by the poor.

Some Americans make the argument that smokers, even poor ones, should be paying more in taxes — a tax for their sins. Smokers cost the healthcare system a great deal of money ($170 billion a year, and 8.7% of all spending in the U.S.), and cigarette taxes make those who choose to smoke pay their fair share.

This position, though, assumes that smoking is a choice. Many people who smoke are addicted and were drawn into smoking by advertisements and promotions—or they come from a culture where smoking is common.

Being poor also makes it more difficult to quit smoking. A 2012 study analyzed outcomes for smokers who wanted to quit and were provided cognitive behavioral therapy and nicotine patches. The researchers estimated that study subjects from the highest socio-economic class were over two times more likely to have quit after six months than those from a low-income background. They ascribe this discrepancy to the the stress and exposure to other smokers that comes with poverty.

Smoking cigarettes is terrible for smokers and society in general. It is one of the greatest health issues facing the world. According to the Center for Disease Control, cigarette smoking causes 480,000 deaths per year in the United States alone. Exploring ways to decrease smoking prevalence, such as promoting the most effective smoking cessation methods and decreasing the amount of nicotine in cigarettes, must be a public health priority.

But using tax hikes as the primary weapon against smoking may be both unproductive and inequitable. Rather than helping poor people who smoke, these taxes simply make their lives more challenging.

![]()

Our next post investigates whether you should bribe your children to eat their vegetables. To get notified when we post it → join our email list.

This post was written by Dan Kopf; follow him on Twitter here.