On July 4th, 1850, at around 4 o’clock in the afternoon, Zachary Taylor returned to the White House for supper.

After a lengthy, very hot day of attending outdoor fundraisers, the twelfth President of the United States was ravenously hungry. Despite being warned by his physician that over-indulgence was “imprudent,” Taylor hastily wolfed down a variety of raw vegetables — cucumbers, cabbage, and corn — then treated himself to a jug of iced milk and an enormous bowl of cherries.

An hour later, the President fell violently ill.

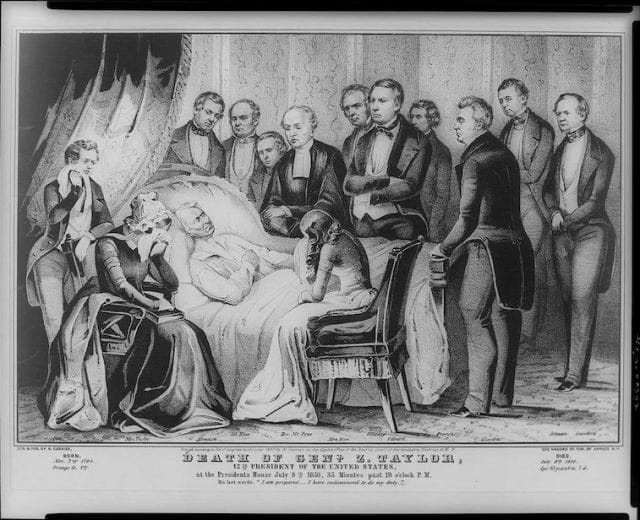

His troubles began with nausea, and soon segued into severe bouts of diarrhea and vomiting. By the following morning, he’d developed a fever. Four doctors descended on the bed-ridden man, each offering various cure-alls: in rapid succession, Taylor was force-fed calomel (a mercury chloride solution meant to induce regurgitation), quinine (a fever reducer), and opium, none of which alleviated his ailments. Five days later, just 17 months into his Presidency, the 65-year-old uttered his last words — “I regret nothing, but am sorry I am about to leave my friends” — and passed away.

The cause of Taylor’s death was listed as gastroenteritis, or “cholera morbus,” a term commonly ascribed to those who died from indeterminable causes in the 19th century. For nearly 150 years, this diagnosis went largely unexplored. Then, a retired professor named Clara Rising dug deeper into the medical records.

Taylor’s symptoms, she surmised, were exactly those exhibited by arsenic poisoning. And the possibility of an assassination wasn’t so unreasonable: with America on the brink of civil war, Taylor’s death had come just months before he was expected to veto several bills proposing the expansion of slavery. Plenty of Southerners had wished him dead.

In her pursuit of the truth, Dr. Rising embarked on a long, strange journey, which involved convincing Taylor’s distant relatives, and the U.S. government, to exhume the rotting body of the long-dead President — all so modern technology could answer one critical question:

Was President Zachary Taylor murdered?

“Old Rough and Ready”

A campaign banner for Whig presidential candidate Zachary Taylor, c.1847; via Library of Congress

Zachary Taylor earned his name as a military man, first as a captain in the War of 1812, and later as a colonel during the Black Hawk War. Relying on his reputation as a ruthless killer, he gradually rose in the ranks of the U.S. Army, eventually securing two major victories during the Mexican-American War of 1845.

Subsequently, Taylor became “America’s most popular figure,” a national hero celebrated for being both a stoic leader and a man who shared in his troops’ hardships. Strongly urged by the Whig Party, Taylor ran for President on the 1848 ticket; despite his utter lack of interest in politics and an incredibly vague platform, he won, and assumed the office on March 4, 1849.

As expected, Taylor was wholly unexceptional as President. During a time when America was becoming increasingly divided as a nation and needed strong leadership, he withdrew from Congress and his cabinet. Much to the chagrin of slave-owning Southerners, Taylor, a slave-owning Southerner himself, largely ignored efforts to legalize slavery in the newly-minted Western States, instead sympathizing more with abolitionists. In the months leading up to the President’s demise, he increasingly became a polarizing figure: many of the pro-slavery Southerners who’d elected him felt betrayed and angered.

After Taylor died, pro-slavery Vice President Millard Fillmore assumed office and swiftly passed the Compromise of 1850, allowing slavery in several Western states; everything Taylor had worked against came forward and was passed by both houses of Congress. Though there were quiet murmurings that the President had been poisoned, none of these suspicions were medically investigated.

Then, more than a century later, Clara Rising came along.

Rising the President

Clara Rising; via C-Span

In the mid-1980s, Clara Rising, a retired University of Florida humanities professor, was dining with a history buff friend when Zachary Taylor’s death came up. “It is a bit suspicious, isn’t it?” the friend asked. “I wouldn’t be surprised if he was poisoned.”

Intrigued by the concept, Rising decided to do some research. While pouring over records of the White House at the time, she was at first struck by the utter lack of security. “In those days, there was no FBI, no Secret Service,” she told C-Span. “Mrs.Taylor often complained that there were strangers wandering around in her bedroom.” Digging deeper into the medical reports of Taylor’s death, she discovered that his reported symptoms were almost identical to those of arsenic poisoning.

Rising knew that if she could get her hands on a Zachary Taylor hair sample, she’d be able to send it into a lab to test for arsenic, a substance which can remain present in the human body for centuries. She searched far and wide for existing hair samples, and found two: one at the Smithsonian Museum in Washington DC, and the other in New Orleans. But both failed to be useful: the first had been “compromised” by pesticides years earlier, and the second turned out to belong to Andrew Jackson, not Taylor.

Rising realized that, in order to conclusively determine whether or not Taylor had been poisoned, she’d have to dig up the President and procure a sample directly from his body. To do so, she needed permission from his distant relatives.

“I wrote to every address, every ‘Taylor,’ and hounded every source I could find,” she recalled. “And finally, I found his closest relative, a man named John McIlhenny.”

McIlhenny, at 84 years old, was the great-great-great grandson of President Taylor (on his mother’s side) and also, coincidently, a relative of the inventor of Tabasco sauce. After four days of sit-down interviews with Rising, he pronounced that “Zachary would be delighted to be exhumed…if it meant getting to the bottom of the truth.”

With the approval of Taylor’s relative, Rising presented her case to Jefferson County, Kentucky Coroner, Dr. Richard Greathouse, who then had to secure the blessing of the Department of Veterans Affairs, the administrator of Zachary Taylor National Cemetery, where Taylor was (and still is) entombed.

Taylor’s body being exhumed; via C-Span

On June 17, 1991, Rising, accompanied by several forensic pathologists and 200 witnesses, opened Taylor’s musty crypt, removed his heavy, black walnut casket, and wheeled it into a nearby hearse.

At Dr. Greathouse’s laboratory, the first order of business was to crack open the coffin. This proved to be more difficult than anticipated: the wood had decomposed, and all that remained was a sealed, metal sarcophagus, which the staff had to maul with a power saw.

Also present in the room was Kentucky State Medical Examiner George “Dr. Death” Nichols, whose duty it was to collect and analyze samples from the corpse.

“We finally got the lid off, and there were Zachary Taylor’s fully dressed remains,” he tells us over the phone. “I’d never met a president before…he didn’t offer much in the way of conversation.”

According to Nichols, the President was “dried out like a sponge,” and was completely devoid of body tissue. All that remained was his “seriously leathered” skin, his body hair, and his skeleton (complete with surprisingly well-maintained teeth).

To test for the arsenic, Nichols collected various dental, bone, and hair samples, and sent them to three different facilities: The first batch went to the State Toxicology Laboratory, where it was tested using colorimetric analysis (the use of a color agent to detect trace elements). A second batch went to the University of Louisville to be scanned with an electron microscope equipped with x-ray diffraction analysis (allowing for close-up molecular views of the follicles). The final batch accompanied Nichols on an airplane to Oak Ridge National Lab for neutron activation analysis, a fairly new technique in which a sample is “bombarded with neutrons, causing the elements to form radioactive isotopes.”

Dr. Nichols at work; via Commonwealth Medical Legal Services

Several weeks later, Nichols released his final opinion in a brief report entitled “Results of Exhumation of Zachary Taylor”:

“[Though] the symptoms which he exhibited and the rapidity of his death are clearly consistent with acute arsenic poisoning, it is my opinion that Zachary Taylor died as the result of one of a myriad of natural diseases which would have produced the symptoms of gastroenteritis. Final Opinion: The manner of death is natural.”

While the tests on Taylor’s remains yielded trace amounts of arsenic (1.9 parts per million in the hair samples, and 3 ppm in the fingernails), Nichols concluded that these amounts would’ve had to be “at least 200 to 1,000 times higher” to prove any inkling of foul play. Humans, he adds, naturally have anywhere from 0.2 to 0.6 ppm of the element present in their bodies at any given time, as it’s naturally present in the environment. Still, while Nichols’ ruled out arsenic poisoning, he admits it may well have been another type of poison that did him in.

“I’ve investigated at least a dozen other deaths due to arsenic, and I’ve seen it used in everything from Hershey’s Chocolate Syrup to Big Red chewing gum,” he says. “It’s entirely possible Taylor was poisoned — but it certainly wasn’t arsenic.”

Beyond ruling out arsenic, Nichols adds that, given the condition and age of Taylor’s corpse, there was little else that could’ve been done to test other substances. After years of being hounded for a definitive conclusion on the nature of Taylor’s death, he’s grown content in his uncertainty.

“The older I get, the happier I am with the answer ‘I don’t know,’” he chuckles. “It removes the bullshit.”

All for Naught

Taylor on his death bed in the White House, c. July, 1850; via Library of Congress

When the media caught word of the lab results (which didn’t make for a good headline), they thoroughly lambasted Clara Rising, the researcher who’d ordered the exhumation.

“Sometimes there are good reasons for tampering with a grave; serious historical evidence establishing the possibility that President Taylor was assassinated would be one,” reads a 1991 The New York Times editorial. “But Ms. Rising has produced no such evidence, only a hypothesis…all that’s been revealed is a cavalier contempt for the dead.”

A writer at The Washington Post declared Rising a “conspiracy theorist,” and publically shamed her in a column about the foiled attempts of “loonies” to reverse history. Following suit, The New Republic denounced Rising’s effort as “sacrilege.” Even Rising’s academic peers expressed no sympathy: presidential biographer Elbert Smith called her plan “sheer nonsense,” while historian Shelby Foote critiqued the ordeal as a “pointless engagement.”

Amidst all of this, Rising held her head high.

“We found the truth,” she defended, a day after the results came in. “Certainly, the 628,000 [who died in the Civil War] would say it was worth looking into.”

In 2007, Rising published “The Taylor File,” chronicling her decades-long quest, but it appears the book fell flat. Its Amazon page shows only one review, rated 1 out of 5 stars: “The President’s remains were disturbed for nothing, thanks to Clara Rising, author of this book.”

Three years later, she passed away in her Florida home.

***

Today, Zachary Taylor is back in his lofty crypt, resting beside his wife, Margaret. Nestled in a colorful row of crab apple trees, an inconspicuous plaque lists his victorious battles, presidential appointment, and faithful duty to the nation. And then, the inscription concludes in a fittingly vague manner:

“Died in office.”

Despite the disruption of his eternal rest, we’ll never know how.

To get occasional notifications when we write blog posts, please sign up for our email list. A version of this article first appeared July 2, 2015.