“If you can dodge a wrench, you can dodge a ball.”

![]()

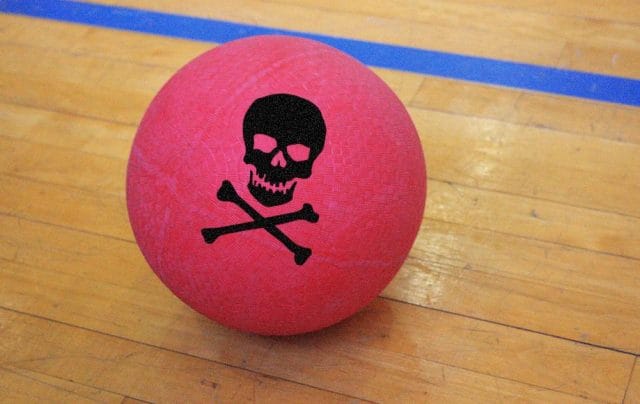

With trembling knees and sweaty palms, the requisite nerd cowers in a dark corner of his school’s gymnasium. He bobbles back and forth with uncertainty, as if running into invisible walls: nowhere to hide.

A herd of ogreish seniors lumbers toward him now, arms cocked and fully loaded. Our dear protagonist is a sitting duck at the mercy of a teenage firing squad; in mere seconds, he’ll be pummeled by a barrage of red rubber balls.

As kids, most of us played the game; as adults, we seem to either look back on dodgeball with warm nostalgia or unbridled terror. But at some juncture, the game became the diabolical bastard of American recreational activities, castigated by physical educators, pundits, and the media. It has been denounced by local, state, and federal organizations, and it is increasingly being banned by public schools.

But how exactly did dodgeball morph into a scapegoat for sporting cruelty?

Deadly Theories of Origin

Source: Jake Hester

Dodgeball’s origins are shrouded in doubt: no credible sources exist. Yet, despite the game’s spotty history, the Internet has an amalgam of theories it wants to share with us — all of which are brutally violent (and none of which are factually verifiable). They serve as a prime example of how violence has pervaded dodgeball’s societal perceptions.

According to one source, dodgeball can be traced back two-hundred years to Africa, where it was “a deadly game.” The author contends that it was once played with “large rocks and petrified matter,” and was “used as an intense workout for tribes:”

“Each competitor would attempt to hit his opponent with the rock to injure or incapacitate him. Once a player was hit, the attacker would attempt to pelt him with more rocks to finish him off. It would be the responsibility of the teammates of the fallen competitor to try and defend him. This was a great way to encourage the tribesman…to take out the weak and protect their own.”

From here, contends another amatuer historian, the game was brought to the United States by an observant (but non-participating) missionary in the late 1800s. Rocks were supposedly substituted for “broken house-bricks,” and the game became known as “deathbrick.” During the game’s “golden age” from 1910 to the late 1920s, it was adapted as a sport at Princeton and Yale, and a “National Deathbrick League” was instituted. According to the questionable source, deathbrick is “alive and well today:”

“Some amateurs continue to play deathbrick with reproduction equipment, and the traditional thunk of brick on cranium continues to be heard in council estates and in bus shelters the world over.”

While these “theories” are clearly dubious, they propagate the notion that dodgeball is a violent, cruel playground sport, and have, in part, prompted legislators to question its place in the school system.

Proud Member of the ‘P.E. Hall of Shame’

A friendly game of dodgeball at a local church; Source: Faith Bible Church

Today’s variation of dodgeball is a far cry from its alleged predecessors. Essentially, players split into teams and throw balls at each other; whoever gets hit is out. In sanctioned league play, the weapon of choice is a 7-inch foam ball, but the vast majority of games (ie. those played by children K-12) utilize rubber kickballs. To alleviate any modicum of protest, some programs stock balls with “fully-padded canvas surfaces.”

But no amount of candy-coating can detract from dodgeball opponents’ pervading thesis: the game is a “battlefield” that subjects kids to unnecessary, brutal confrontation. For over two decades, dodgeball has been met with fierce antagonism.

As early as 1986, sporting journal Physical Education, Recreation and Dance, published articles with titles like ”Premeditated Murder: Let’s Bump Off Killer Ball,” which denounced “elimination” sports.

In 1992, Neil Williams, chairman of the physical education department at Eastern Connecticut University, published an extensive report titled “The Physical Education Hall of Shame.” The paper highlighted seven games Williams found to be “riddled with dishonor and ignominy;” dodgeball topped the list, accompanied by this nugget of high praise:

“The all-time classic! The main objective is to attempt to inflict pain, harm, injury, and embarrassment on one’s opponents, and have a good laugh doing it. Is this the worst PE game ever?”

Williams went on to remind his colleagues that “dodgeball endangers the health and well-being of students, and the security of [physical education] jobs,” and called it “litigation waiting to happen.” (Also appearing in Williams’ ‘Hall of Shame’ list: kickball, red rover, tag, and musical chairs.)

“Is ‘Killer Ball’ an educational experience?” asks the JOPERD (1986)

In 1996, the condemnation of dodgeball continued when Department of Education consultant Ambrose Brazelton called the game “an example of what’s wrong with schools — and where kids feel like targets,” and called for a statewide ban in Ohio.

The National Association for Sport and Physical Education (NASPE) — a body that oversees national PE standards and represents the field’s 18,000 educators — released its official “Position on Dodgeball in Physical Education” in 2006, in the wake of GSN’s Extreme Dodgeball television show:

“NASPE believes that dodgeball is not an appropriate activity for K-12 school physical education programs. Dodgeball provides limited opportunities for everyone in the class, especially the slower, less agile students who need the activity the most.

Being targeted because they are the “weaker” players, and being hit by a hard-thrown ball, does not help kids to develop confidence — certainly not the student who gets hit hard in the stomach, head, or groin. And it is not appropriate to teach our children that you win by hurting others.”

Last year, Cheryl Richardson, NASPE’s senior director, said that “dodgeball should not be part of any curriculum, ever.” Other organizations have adapted this stance.

Concerned Adults and Students for Physical Education Reform (CASPER), an organization which “seeks to eliminate humiliating and wasteful practices” in sports, was founded by P.E. professor Cathrine Himberg after learning of her son’s experiences playing dodgeball. Today, CASPER says the activity “reinforces low self-esteem in unathletic and clumsy children,” and advocates for its ban in K-12 programs.

Dodgeball’s Moral Castigation

Freaks and Geeks’ take on Dodgeball

In the 2004 comedy Dodgeball: A True Underdog Story, a group of gym-goers is shown an instructional dodgeball video from the 1950s which opens with a re-creation of the sport’s supposed invention: two Chinese men sit in an opium den, throwing severed heads at each other with irrepressible joy.

The scene is one of many that satirizes perceptions of the game as violent; since the film’s release, American society has had a dodgeball feeding frenzy. The media gave the game a slew of aliases — “murderball,” “warball,” “killerball,” “poisonball” — and entrepreneurs capitalized on its violent perceptions.

Cable television’s Game Show Network debuted Extreme Dodgeball, that played up the game’s tendency to “make one person the target.” Features of the show included balls “twice the size of regulation,” and a “Dead Man Walking” round in which one competitor would be fitted with an orange headband and deemed the “sole target.” Likewise, bonus points were given to players who “killed” opponents with the “Big Ball.”

In a network meeting, GSN executives discussed “developing and executing extreme strategies to annihilate opponents,” and proposed the integration of terms like “throw-to-kill-ratios” and “headshots.”

Popular culture teems with hyperbolized commentary on dodgeball’s damaging nature: Rick Riordan’s 2006 children’s fantasy novel Percy Jackson and the Sea of Monsters features a young protagonist who is sentenced to a “dodgeball game to the death” against cannibal giants who want to eat him; a character in the television show Glee makes it his mission to ban the sport, and calls it a “modern day stoning;” an episode of the Simpsons showcases a new gym teacher who fiercely throws balls at students while screaming “Bombardment!”

While some outlets clearly mock the alleged violence of dodgeball, others contribute to NASPE’s agenda of exposing the game as “sadistic” and “both physically and psychologically damaging.”

A “Nanny State” Victim

Last March, there was an outcry when school board members in Windham, New Hampshire, voted 4-1 to ban dodgeball district-wide. After a parent complained about the “physically aggressive nature” of the game, administrators launched an investigation and concluded that they were in agreeance with NASPE’s stance: games that use “human targets” encourage bullying. Windham’s superintendent, Dr. Henry LaBranche, reinforced this:

“We spend a lot of time making sure our kids are violence free. Here we have games where we use children as targets. That seems to be counter to what we are trying to accomplish with our anti-bullying campaign.”

During the decisive hearing, the school board’s vice chairman, Stephanie Wimmer, even likened dodgeball to the Sandy Hook tragedy, in which 20 children were shot to death:

“When I saw the names of some of these games — unfortunately guys, we live in a world where 20 babies were slaughtered. We need to take violence out of our schools and not teach it.”

![]()

Windham’s dodgeball ban evoked accusations that America is increasingly becoming a “wussified nanny state,” in which children are coddled and over-protected. But this wasn’t the first time the game was outlawed by a school: dodgeball seems to historically encounter backlash in the wake of school shootings.

Following the Columbine massacre in 1999, the Austin Independent School District in Texas ostensibly became the nation’s first to ban the dodgeball. Diane Farr, a curriculum specialist at the time, emphasized the district’s decision in The New York Times, stating,”With Columbine and all the violence that we are having, we have to be very careful with how we teach our children.”

Soon after, multiple districts in Virginia (Fairfax County), Florida (Oslo), New York (Long Island), Maine, and Massachusetts formally banned the game from school curriculums — some of which still enforce the bans today.

Sudden Death

Dennis Senibaldi, a school board member and dodgeball proponent, gauges the dangers of the game against glorified sports like football: “This is dodgeball, it is American pie,” he said. “To suggest concussions and stuff (from dodgeball) you’d have to ask yourself, compared to football – how many concussions? How many knee injuries?” Yet, he adds, schools aren’t clamoring to ban the pigskin.

Seinibaldi raises a good question: if schools are really going to continue to ban dodgeball, shouldn’t they target more destructive sports? Certainly, there are plenty to choose from:

Based on deaths per 100,000 participants from 1982-2011; Data via National Center for Catastrophic Sport Injury Research

And strangely lost in the hullabaloo of administrators and school officials are the quieted opinions of the children themselves.

NASPE and other organizations tell the story that the only children who enjoy dodgeball are the “aggressors” — the big, burly playground equivalents of junkyard dogs, but Lindsay Stagg — a diminutive sixth-grader from New Hampshire, seems to hold a different view.

“I think it’s really fun,” she says. “It doesn’t even hurt if it hits you.”

This post was written by Zachary Crockett. Follow him on Twitter here, or Google Plus here.