In America, we love to talk about crime. Usually, the rhetoric is focused on the acts we can see: bank heists, stolen bicycles and cars, alleyway robberies.

But often, the more egregious crimes are the ones that are “unseen” — those that happen behind closed doors in Wall Street suites, or over late-night email exchanges on virtual private networks. Among these, one stands out as particularly heinous: wage theft.

In its simplest terms, wage theft refers to instances in which workers are not paid the legal and/or contractual wages promised by their employers. This includes the non-payment of overtime hours, the failure to give workers a final check upon leaving a job, paying a worker less than minimum wage, or, most flagrantly, just flat out not paying a worker at all.

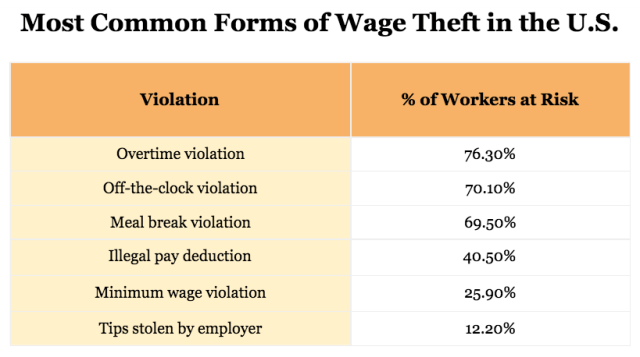

Most commonly, wage theft comes in the form of overtime violations:

Source: Center for Urban Economic Development study (survey size = 4,387 low-wage workers in Chicago, Los Angeles, and New York City)

When it comes to ripping employees off, employers do not discriminate: wage theft exists in all professions, and affects all workers, regardless of gender, race, or legal status. Generally though, it is more prevalent among lower income jobs.

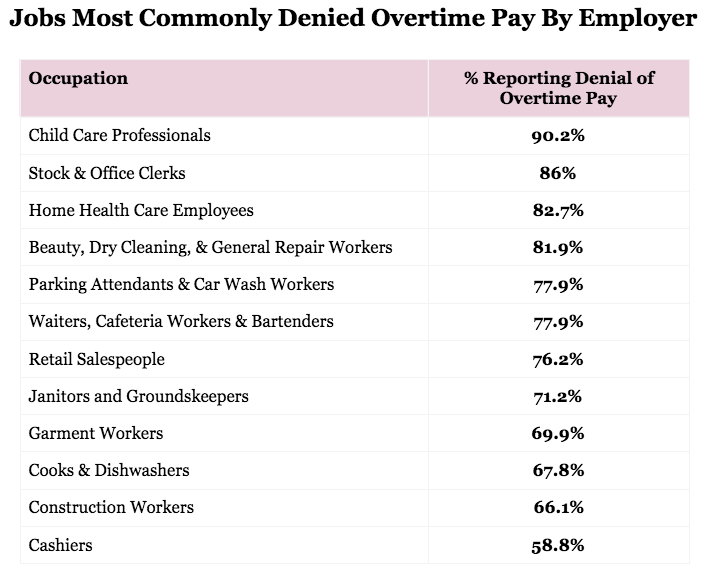

Here’s a breakdown of the fields most affected by employers who illegally deny overtime pay (note that the average salary on this list is roughly $19,000 per year):

Source: Bernhardt, A. et al. (2009). “Broken Laws, Unprotected Workers – Violation of Employment and Labor Laws in America’s Cities,” p.76

Like all crimes, most instances of wage theft go unreported, making the scope of violations difficult to measure. Though the attempts to quantify these instances have yielded unsettling answers.

In a 2008 study, the Center for Urban Economic Development surveyed 4,387 workers in low-wage industries in Chicago, Los Angeles, and New York City (the three largest cities in the U.S.), and found that some 76% of full-time workers were victims of wage theft. Based on a yearly minimum wage salary of $17,616, this amounted to an estimated average of $2,634 in lost wages — nearly 15% of each worker’s salary.

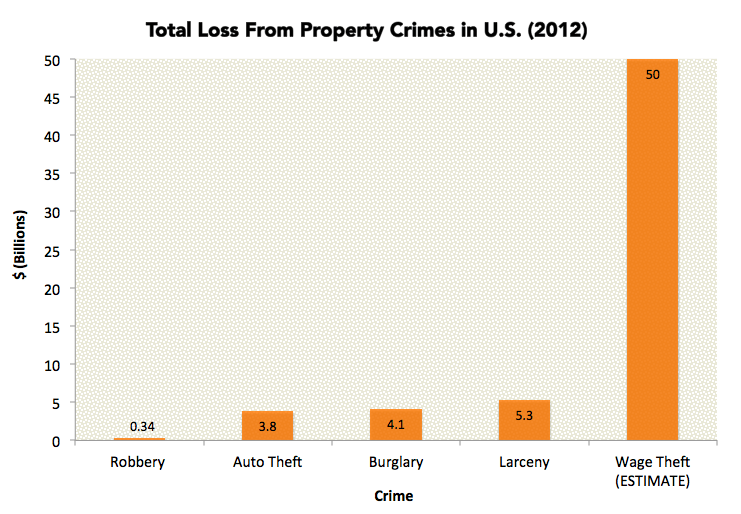

In total, unfairly withheld wages in these three cities topped $3 billion. Generalizing this for the rest of the U.S.’s low-wage workforce (some 30 million people), researchers estimate that wage theft could be costing Americans upwards of $50 billion per year.

For comparison’s sake, let’s gauge this estimated figure against FBI data for other reported property crimes (robbery, auto theft, burglary, and larceny):

Source: Robbery, auto theft, burglary, and larceny data taken from the FBI’s 2012 crime report, and represent reported incidents only; wage theft estimate extrapolated from the Center for Urban Economic Development’s 2008 study

Hypotheticals aside, let’s take a look at the actual hard data that exist on wage labor crimes.

Last year, the Economic Policy Institute made what is, to date, the most ambitious attempt to quantify the extent of reported wage theft in the U.S. To do so, they canvassed the labor departments of 44 states, analyzed the U.S. Department of Labor’s annual budget, and poured through a vast number of civil litigation settlements.

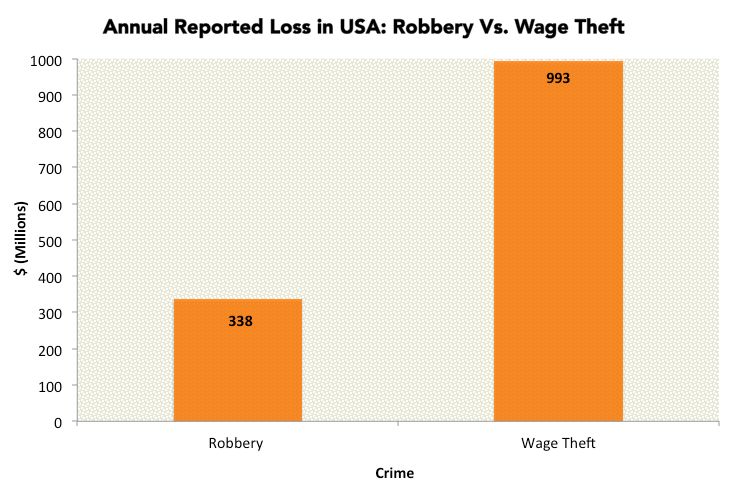

They determined that “the total amount of money recovered for the victims of wage theft who retained private lawyers or complained to federal or state agencies was at least $933 million.” Of course, this should be taken with a grain of salt: six states didn’t report their data, and an estimated 70% of property crimes go unreported in general — so this amount is like to be astronomically higher.

Even using this diminished figure, reported wage theft outpaces reported robberies in the U.S. by nearly 300%.

Source: Robbery data taken from the FBI’s 2012 crime report (reported incidents only); wage theft figure via the Economic Policy Insitute

Though not as overt as, say, an office break-in, wage theft is infinitely more detrimental to American laborers. Yet because it is so difficult to trace, and has yet to be meaningfully measured, it hasn’t been as effectively combatted.

The sad reality is that the vast majority of wage theft crimes are committed against low-wage workers who can’t afford a good lawyer, or time off to go to court. Even with pro-bono services and legal help, most unpaid workers don’t want to risk losing their jobs by calling out their employers. As a result, wage theft is vastly underreported.

There is a rather meager silver lining to all of this: the number of wage theft cases filed in federal court is on rise. In 2013, there were 7,764 reported cases, up 5,302 in 2008. Gauged with figures from twenty years ago, contested wage theft cases have increased by 500%.

This post was written by Zachary Crockett. You can follow him on Twitter here.

To get occasional notifications when we write blog posts, please sign up for our email list.