![]()

Mickey Mouse is, in the words of one copyright expert, “a fucking powerhouse.”

The lovable rodent, who sports bright red shorts, a pair of gigantic yellow shoes, and circular ears, has achieved, in his 87 years, what no other animated character has: He has won an Academy Award. He has spawned social clubs, theme parks, and every piece of merchandise imaginable. He has a worldwide brand awareness of 97% — higher than Santa Claus. For his efforts, Forbes has dubbed him the world’s “richest fictional billionaire,” placing his estimated worth to Disney at $5.8 billion per year.

For Disney, Mickey Mouse is not just a huge money maker, but the company’s most coveted piece of intellectual property. Mickey is Disney, and Disney is Mickey: the two are simply one and the same, and nothing is more important to Disney than his well-being. (“I love Mickey Mouse more than any woman I have ever known,” Walt Disney once famously said).

For this reason, Disney has done everything in its power to make sure it retains the copyright on Mickey — even if that means changing federal statutes. Every time Mickey’s copyright is about to expire, Disney spends millions lobbying Congress for extensions, and trading campaign contributions for legislative support. With crushing legal force, they’ve squelched anyone who attempts to disagree with them.

In the age of the Internet, where vast swaths of creative material are freely available, the central question raised by Mickey Mouse’s copyright ordeal is especially pertinent: Which is more important, a robust public domain, or the well-being of private interests?

The Invention of Mickey Mouse

Three and a half years after founding his Los Angeles animation studio, Walt Disney was approached by his distributor, Charles Mintz, with an opportunity: Universal Studios was looking for a cartoon character.

Disney, who had only enjoyed moderate success up to that point and was still an unknown in the animation world, happily took the job. In the early months of 1927, the 26-year-old Disney, along with his chief animator Ub Iwerks, designed Oswald the Lucky Rabbit — a rather saucy, anthropomorphic creature — and Mintz inked the deal with Universal. Oswald became a huge hit, and as a result, Walt Disney Studios ballooned to 20 employees.

In 1928, at the peak of Oswald’s success, Mintz went behind Disney’s back, stealing away nearly his entire animation team and re-signing them to a contract with Universal. When Disney’s own contract with Mintz expired, he found himself stripped of not only his creation, but of his staff of animators. In the process, Disney learned a valuable lesson: he had to “always make sure that [he] owned all rights to the characters produced by [his] company.”

“All he could say, over and over, was that he’d never work for anyone again as long as he lived,” later recalled his wife, Lillian. “He’d be his own boss.”

Several months later, Disney and Ub Iwerks, who’d stayed loyal to him as an animator, hit the drawing board. In Disney’s own account, Mickey Mouse was conceived out of desperation:

“We had to create a new character in a hurry to survive. And find a market for it. We canvassed all the animal characters we thought suitable for the movie fable fashion of the time. All the good ones—the ones that would have instant appeal and would be comparatively easy to draw—seemed to have been pre-empted by the other companies in the cartoon animal field. Finally, a mouse was suggested, debated and put on the drawing boards as the best bet. That was Mickey.”

On November 18, 1928, Mickey Mouse made his official debut, in an animated short called “Steamboat Willie.” Within five years, he became Hollywood’s inanimate poster child, raking in nearly $1 million a year ($18 million in 2015 dollars) in merchandise sales, soliciting Academy Award nominations, and inspiring children around the world.

Having learned from his distributor’s previous betrayal, Disney clung to Mickey with an iron grip. But like all fictional characters, Mickey faced an imminent future in the public domain — didn’t he?

How Mickey Has Evaded Copyright Law

Copyright law in America long predated Mickey Mouse.

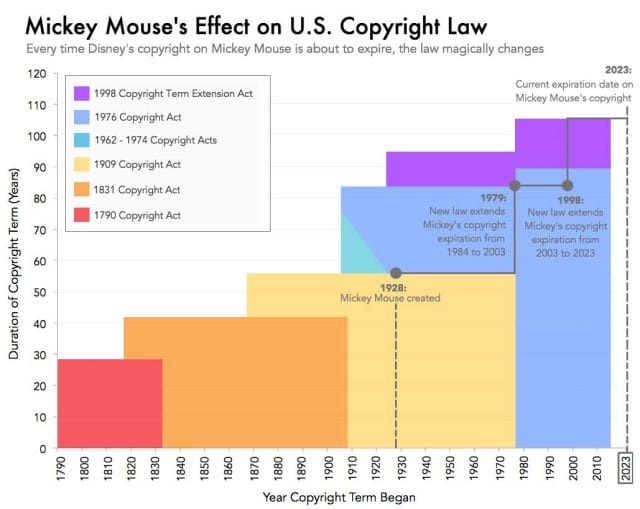

The first of these laws, the Copyright Act of 1790, stipulated that creative works were entitled to up to 28 years of protection (14 years, plus an additional “renewal” period of 14 years, supposing the original hadn’t died). This was followed by an 1831 act, which extended the copyright period to a max of 42 years, and a 1909 act, which elongated that period again, to 56 years. As the Art Law Journal clarifies, “very few works actually maintained [these] copyright durations”: only a fraction of those who secured copyrights protected them, or opted to renew them.

Mickey Mouse was brought into the world in 1928, under the 1909 Copyright Act, entitling him to 56 years of protection under the law — no more. In accordance with the law, his copyright was set to expire in 1984.

As this date drew near, Disney (the corporation) grew increasingly anxious. By this time, Mickey was worth billions in annual revenue, and had become the face of the company; losing him to the public domain would be a massive financial blow. Quietly, Disney took to Washington and began lobbying Congress for new copyright legislation.

In the chart below, we’ve visualized every major copyright act, and overlaid how these acts have kept Mickey Mouse out of the public domain:

Zachary Crockett, Priceonomics; data via Tom W. Bell

Disney’s efforts, and those of other multinational corporations with soon-expiring intellectual property, seem to have paid off. In 1976 — just 8 years prior to Mickey’s expiration — Congress completely overhauled U.S. copyright law to conform with European standards. This new law expanded already-published corporate copyrights from 56 years to a maximum of 75 years. All works published prior to 1922 immediately entered the public domain; all works published after 1922 (including Mickey Mouse) were entitled to the full 75 years of protection. Just like that, Mickey Mouse extended his copyright death 19 years — from 1984 to 2003.

By the mid-1990s, Disney again began to feel the impending doom. In addition to the 2003 expiration of Mickey’s copyright, Pluto was set to expire in 2005, Goofy in 2007, and Donald Duck in 2009. The gang, collectively worth billions, had to be retained, so Disney began lobbying again.

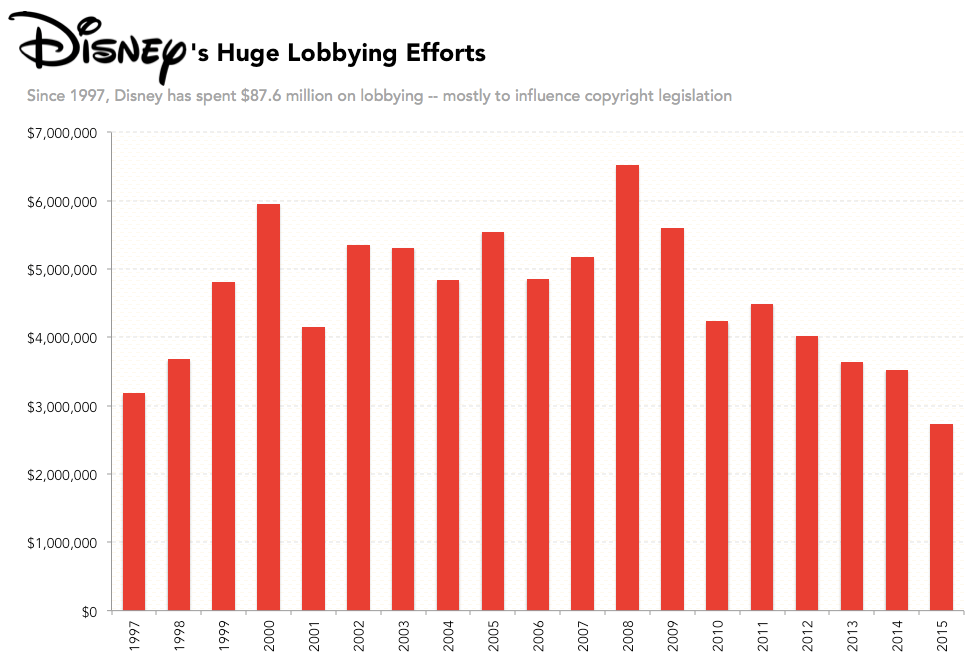

In 1997, Congress introduced the Copyright Term Extension Act, which proposed to extend corporate copyrights again — this time, from 75 to 95 years. To ensure the bill passed, Disney cozied up to legislators.

Watchdog records show that the Disney Political Action Committee (PAC) paid out a total of $149,612 in direct campaign contributions to those considering the bill. Of the bill’s 25 sponsors (12 in the Senate, and 13 in the House), 19 received money from Disney’s CEO, Michael Eisner. In one instance, Eisner paid Senate Majority Leader Trent Lott (R-MS) $1,000 on the very same day that he signed on as a co-sponsor.

Zachary Crockett, Priceonomics; data via Open Secrets; figures adjusted for inflation

“We regard our lobbying as proprietary to us,” Disney spokesman Thomas J. Deegan stated, when confronted by CNN in 1998. “We don’t wish to talk about it.”

While it is impossible to say for certain whether or not Disney’s efforts directly impacted politics, the results heavily worked out in their favor: the bill quietly and unanimously passed in the House and Senate with no public hearings, no debate, no notice to the public, and no roll call.

On October 27, 1998, Mickey Mouse’s copyright was extended another 20 years, to 2023.

In the entire congressional committee, only one man — Senator Hank Brown — opposed the bill. “The real incentive [was] for corporate owners that bought copyrights to lobby Congress for another 20 years of revenue,” he later said. “I thought it was a moral outrage. There wasn’t anyone speaking out for the public interest.”

Silent Protests

Via Flickr

While Mickey Mouse’s apparent ability to influence the law has been criticized, any major effort to rile up the public has been squelched by Disney.

In the early 1970s, underground cartoonist Dan O’Neil published a series of “raunchy, Mickey-taunting comics”, depicting the mouse in various unsavory situations. He then formed a group called the “Air Pirates” (named after a group of Mickey’s villains from 1930s-era films), with the intent to alter the character to his own liking.

“Throughout my childhood, Mickey Mouse was used as a placebo to lull me into thinking everything was alright,” one of his accomplices later stated. “But I found the happy-ever-after world of Walt and Mickey Mouse to be a poor half-truth. ‘Air Pirates’ shows that Mickey doesn’t always win.”

Eventually though, Mickey did win: Disney slapped O’Neil with a copyright infringement suit, and eventually won a settlement of nearly $200,000.

A underground cartoon from the 1970s inspired by the Air Pirates

In 1979, just a few years after Mickey’s copyright was extended by Congress, O’Neil formed the “Mouse Liberation Front” in protest. He recruited dozens of renegade cartoonists — all upset over the character’s copyright longevity — and barraged comic book conventions with lewd pictures of the mouse. Disney immediately threatened another lawsuit, and O’Neil abandoned his campaign.

Years later, in the wake of the 1998 Extension Act, Eric Eldred, an Internet publisher who published works in the public domain, decided to “[challenge] the constitutionality of retroactively extending copyright terms.” Eldred’s counsel argued that Congress’ power to expend copyrights invalidated the Constitution’s claim that copyrights can only be valid for a “limited” time.

In 2003, the case went all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court. But despite mounting support from the public to overturn the extension act, the court upheld it. In the opinion of Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, the language set forth in the Constitution — that the role of the copyright was to “promote the progress of science and useful arts” — did not limit the power of Congress to change the law.

Should Mickey Mouse Be Set Free?

Today, Congress can change the copyright term whenever it sees fit, making it entirely possible that Mickey Mouse’s copyright will be extended again before 2023. But should it? Does Disney’s cajoling of the law serve any positive benefits to society at large, or does it merely further enforce the repertoire of private interests?

Those in favor of copyright extensions generally fall back on three major arguments: 1) Lengthy copyrights are necessary to incentivize the creation of new works; 2) Copyrighted works are an important source of income — not just to copyright holders, but the U.S. at large; and, 3) Copyrights were originally intended to provide income for two generations of descendants; since human lifespan has increased since the original copyright bill in 1790, the copyright term should be appropriately elongated.

“All of these arguments are either demonstrably false or, at best, without foundation in empirical data,” copyright scholar Dennis Karjala tells us over the phone. “The extensions are corporate welfare, plain and simple — and they have caused a lot of harm to the general public.”

Dennis Karjala at a copyright law forum in 2007

But what exactly are the “harms” Karjala is referring to? Why should the public care about copyright extension?

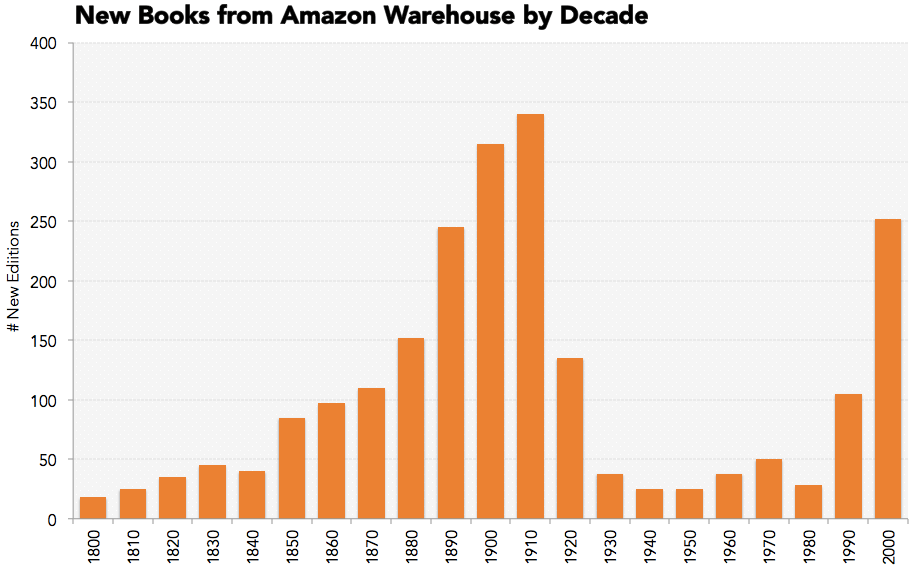

For one, research done by Paul J. Heald, a professor in the University of Illinois School of Law, has shown that copyright can “stifle the availability of work” to the general public. In a 2013 paper entitled How Copyright Keeps Works Disappeared, Heald crawled through more than 2,000 books on Amazon.com, and found that there were more books available from the late 1800s than there were from the 1990s. His conclusion: “Copyright protections had squashed the market for books from the middle of the 20th century, keeping those titles off shelves and out of the hands of the reading public.”

“Copyright correlates significantly with the disappearance of works rather than with their availability,” writes Heald. In essence, his research endorses that copyright “makes books disappear”, and copyright expiration “brings them back to life.”

Priceonomics; Data via How Copyright Keeps Works Disappeared (Heald, 2013)

This particular argument doesn’t seem to apply to Mickey Mouse. After all, it isn’t as if copyright has shelled him off from society: he’s still very much in the public spotlight, and millions of people enjoy him on a daily basis.

Still, Karjala argues that copyright extensions have limited (if not altogether squashed) the public’s freedom to make derivative works. Moreover, he contends that they only serve to boost corporate profits for an elongated period of time (the longer Mickey is copyrighted, the longer competition is minimized, allowing Disney to charge more for its films and merchandise).

“The continued payment of [extended copyright] royalties is a wealth transfer from the U.S. public to current owners of these copyrights,” he writes. “These copyright owners are in most cases large companies and, in any case, may not even be descendants of the original authors whose works created the revenue streams that started flowing many years ago.”

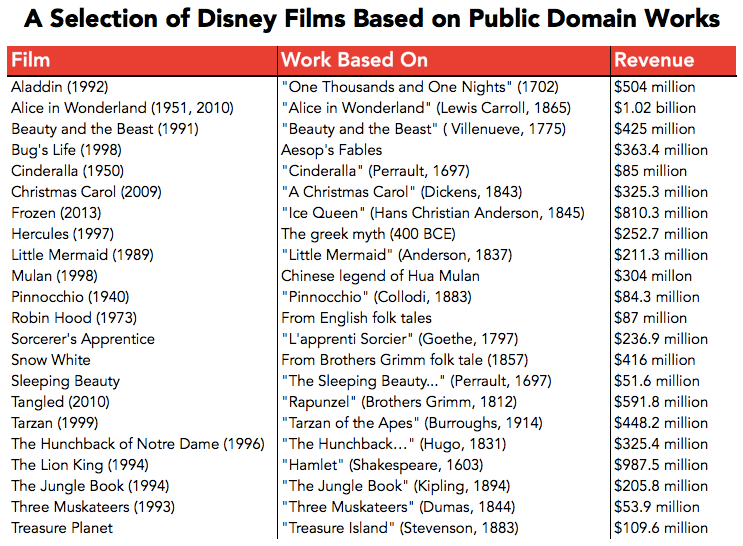

While Disney continues to ardently fight for copyright legislation, more than 50 of its own films — including blockbusters like Alice in Wonderland, Aladdin, Frozen, and The Lion King — are based on works in the public domain:

Zachary Crockett, Priceonomics; data via Forbes

Disney has taken full advantage of expired copyrights without “paying into the system” with its own original characters.

***

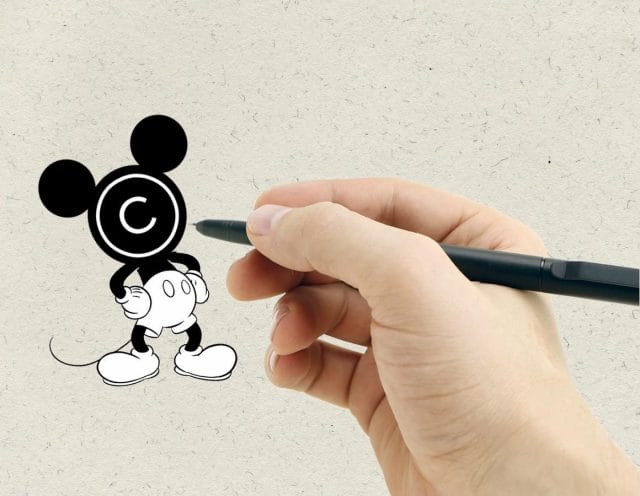

Ultimately, none of this may matter: Even if Mickey’s copyright does expire in 2023, Disney has no less than 19 trademarks on the words “Mickey Mouse” (ranging from television shows and cartoon strips to theme parks and videogames) that could shield him from public use.

While a copyright protects works of art from being manipulated by the public, a trademark “protects words, phrases and symbols used to identify the source of the products or services.”

According a precedent set in a 1979 court case, a trademark can protect a character in the public domain as long as that character has obtained what is called “secondary meaning.” This means that the character and the company are virtually inseparable: upon seeing it, one will immediately identify it with a brand. Copyright lawyer Stephen Carlisle contends that Mickey Mouse would meet this qualification with flying colors, should he need to:

“Disney has made Mickey Mouse so prominent in all of their corporate dealings, that he is effectively the pre-eminent symbol of the Walt Disney Company. There can be little doubt that anyone seeing the image of Mickey Mouse (or even his silhouette), immediately thinks of Disney.”

In other words, Disney has ingrained Mickey Mouse so deeply in its corporate identity that the character is essentially afforded legal protection for eternity, so long as Disney protects him (trademarks last indefinitely, so long as they are renewed).

It’s a sad truth for crusaders of the public domain: the more powerful and recognizable a piece of corporate property is (and thus, the more coveted it is by society at large), the less likely it is to be relinquished.

![]()

Our next post explains why you should tell bankers to take their credit card rewards and shove them up their asses. To get notified when we post it → join our email list.

![]()

This post was written by Zachary Crockett. You can follow him on Twitter at @zzcrockett