Held from August 15 to 18, 1969 on a dairy farm in upstate New York, Woodstock was arguably the most epic music festival in history. It is cited as one of Rolling Stone‘s “50 Moments That Changed the History of Rock and Roll,” and more importantly, as the “definitive nexus for the larger counterculture generation.”

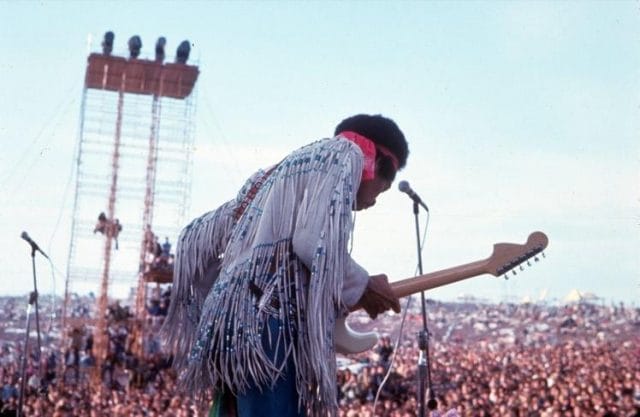

The weekend featured many of the era’s most lauded rock and folk musicians — Jimi Hendrix, Janis Joplin, Joe Cocker, The Grateful Dead, Creedence Clearwater, Carlos Santana — all of whom gave legendary performances before a crowd of 400,000 mud-soaked flower children.

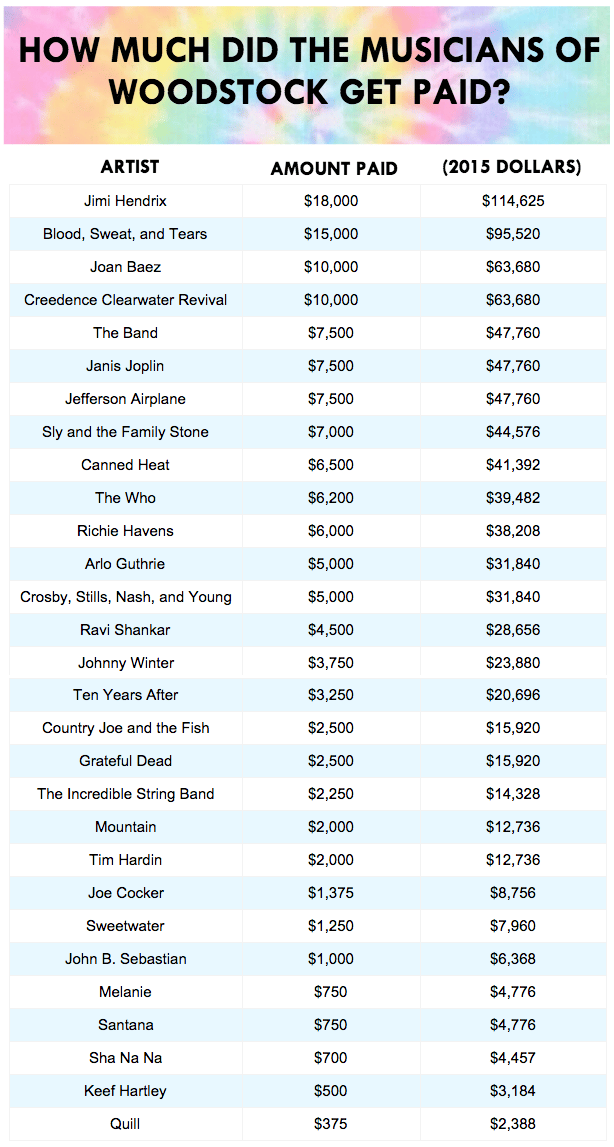

Thanks to an old Variety Magazine chart that recently resurfaced, we now know how much these artists were paid for their efforts — and some figures are rather surprising:

Priceonomics; Data via Variety, Ultimate Guitar

We reached out to Robin E. Green, who operates the Woodstock Museum at New York’s Bethel Woods Center for the Arts; she told us that “this information looks accurate,” and corroborated its authenticity.

The list above includes all but two Woodstock performers (Paul Butterfield Blues Band and Paul Sumner). Additionally, psychedelic rock group Iron Butterfly had been slated to receive $10,000, but never showed up. Though these were the purported prices agreed upon by the artists’ agents and the show’s promoters, there is some speculation that a few of the artists were never paid in full.

Regardless, the prices provide some insight as to how much top acts were commanding in 1969.

Ironically, Hendrix, whose fee leads the list at $18,000 (more than $114,000 in 2015 dollars), played to the smallest crowd of the entire weekend. Slated to close out the festival, he didn’t hit the stage until 8:30 AM Monday morning, mostly due to massive rain delays. By the time he erupted into his now-legendary rendition of “The Star Spangled Banner,” only 30,000 — less than 10% of the festival’s attendees — remained.

Santana’s “Soul Sacrifice” performance at Woodstock launched him into the national spotlight

Blood, Sweat, and Tears’ fee of $15,000 seems equally appropriate: months earlier, the jazz-rock group’s self-titled album had topped the U.S. Billboard charts, produced three Top-5 singles, and earned them a Grammy Award for ‘Album of the Year.’

Joe Cocker, paid a mere $1,375 (~$8,800 in 2015 dollars), was perhaps the best value for the festival’s promoters. His cover of the Beatles’ “With a Little Help From My Friends” is considered one of the most impassioned festival performances of the era.

Santana’s astronomically low fee ($750) doesn’t come as much of a surprise. When he began his 45-minute Saturday afternoon set, he and his group were relatively unknown; his debut album had not yet been released, and he’d only begun to gain an underground following. But as the group’s latin percussion ricocheted off the crowd, Santana quickly gained approval — and by the end of the set, the guitarist had launched himself into the echelons of rock history.

***

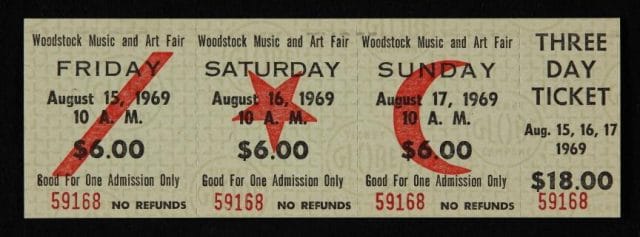

The best deal of all, though, was secured by the festival goers: three-day passes were offered in advance for $18 ($120 in 2015 dollars), or at the gate for $24 ($150). Though some 186,000 tickets were sold, the overwhelming majority of attendees took advantage of the festival’s minimal security and experienced Woodstock gratis. An unprecedented 400,000 people — more than double promoters’ estimate — showed up.

“You couldn’t really wrap your mind around how many people were there,” folk musician David Crosby recalled years later in a Rolling Stone interview. “When we got there, we said, ‘Wait a minute, this is a lot bigger than we thought.’”

A 1969 Woodstock weekend pass ($18)

For its artists, fans, and organizers, Woodstock paid out big in exposure and reputation points — but the festival wasn’t a grand success for everyone involved.

Max Yasgur, the dairy farmer who agreed to host the festival on his plot, was paid a purported sum of $10,000 for his cooperation, but resulting damages to his property exceeded $50,000, and he nearly lost his business. Yasgur’s disgruntled neighbors not only boycotted his milk after the debauchery-filled weekend, but refused to serve him at the local diner and general store.

When promoters came knocking for a revival show the following year, the farmer wanted nothing to do with drugs, sex, and rock & roll. “As far as I know,” he told a New York Times reporter, “I’m going back to running a dairy farm.”

This post was written by Zachary Crockett. You can follow him on Twitter here.

To get occasional notifications when we write blog posts, please sign up for our email list.