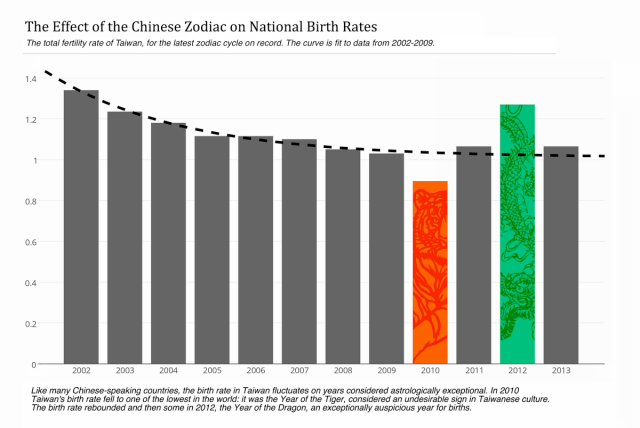

Priceonomics; source: National Statistics, Republic of China (Taiwan)

Chinese New Year was last week, ringing in the Year of the Sheep in Chinese astrology. Much like Western astrology, Chinese astrology predicts a person’s characteristics based on when they were born. But unlike in Western astrology, in Chinese astrology certain times are plainly more desirable than others.

Every year of the Chinese calendar corresponds to a sign in the zodiac cycle: Rat, Ox, Tiger, Rabbit, Dragon, Snake, Horse, Sheep, Monkey, Rooster, Dog, Pig. According to legend, the Jade Emperor selected these animals for the calendar by holding a race requiring they cross a wide river. Each animal’s arrival was different: the rat got there first because he tricked the ox into giving him a ride — thus the first two animals in the cycle are the rat and then the ox. The sheep, monkey, and rooster helped each other across on a raft.

The dragon is the only mythological creature in the zodiac, and comes fifth in the cycle. In many ways the dragon is the legend’s hero. It had no trouble flying across the river, but it stopped on its way to bring rain to parched farmland, and then to help the floundering rabbit cross the river.

According to Chinese astrology, the dragon’s qualities — honesty, magnanimity, courage, and power — manifest in individuals born in a Year of the Dragon. Every astrological sign has its good and bad points: Rats are supposedly clever and charming, but greedy and devious. Oxen are industrious and creative, but also stubborn and poor communicators. Dragons, in addition to their finer points, are quick-tempered and conceited.

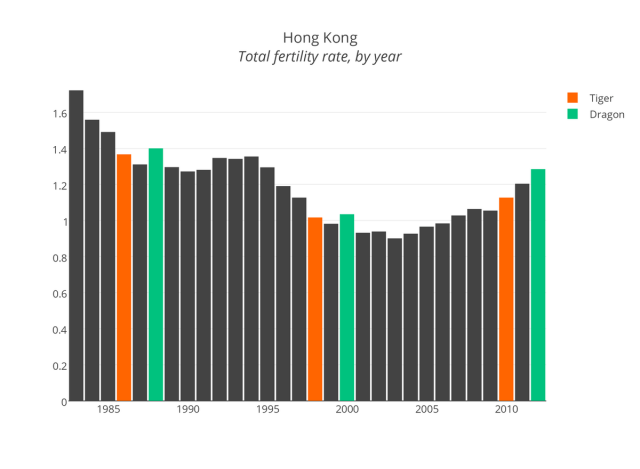

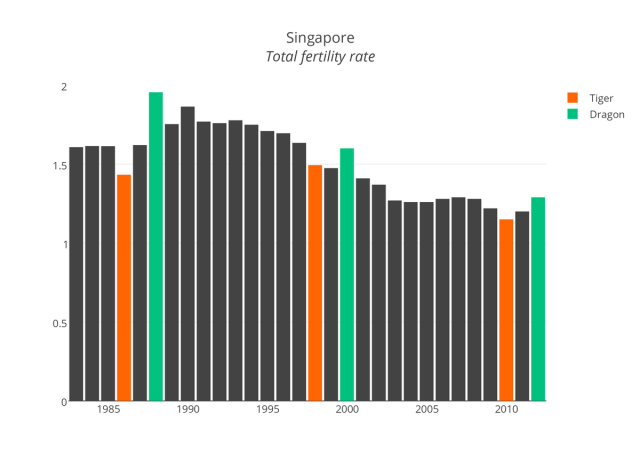

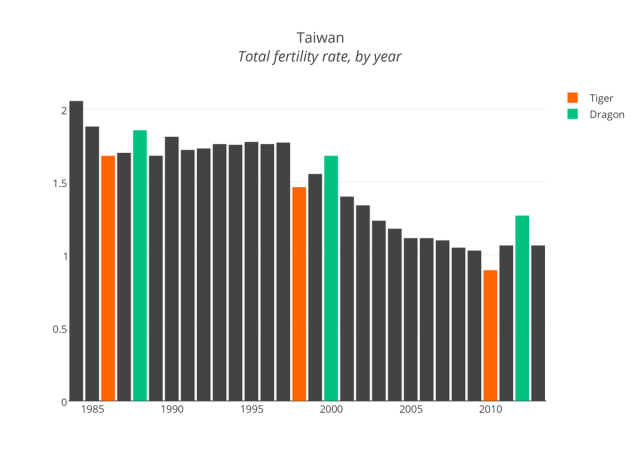

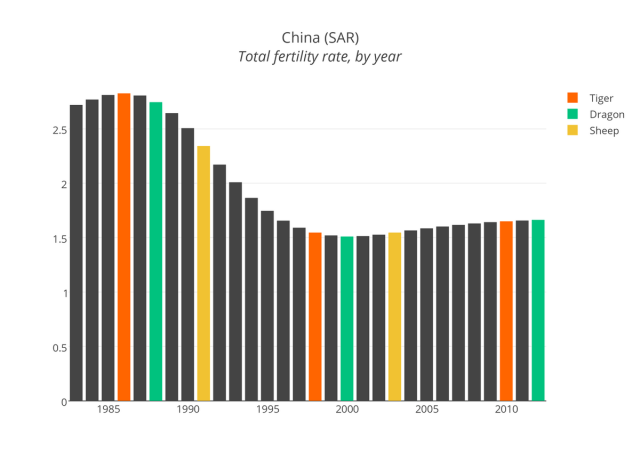

But lots of people still prefer dragons over every other sign. In 2011 and 2012, prospective parents in Hong Kong, Taiwan, and Singapore admitted to consciously timing their pregnancy for a dragon year. Their efforts, and the efforts of previous generations, are reflected in their countries’ national statistics: whenever a Year of the Dragon comes around, the national total fertility rate — the average number of children born per woman “if all women lived to the end of their childbearing years and bore children according to a given fertility rate at each age” — spikes.

Singapore and Taiwan appear to share an aversion against births in the Year of the Tiger, and Hong Kong, it appears, does not. All three countries tend to have more births in the Year of the Dragon; Priceonomics; sources: World Bank, National Statistics Republic of China (Taiwan)

Certain aspects of the zodiac vary between cultures. Taiwan is among the cultures in which the Year of the Tiger is strongly stigmatized. According to an article in Asia Times, it is believed that anyone born under this sign “tends to question authority and is therefore likely to cause trouble for himself, his family or to his employers at some stage of life.”

For the past several decades, Taiwan has reliably seen a large drop in per capita births during Years of the Tiger. In the most recent Year of the Tiger, 2010, Taiwan’s fertility rate was already trending downward, and the tiger drop plummeted it to .895 — one of the lowest in the world. The dragon bump, two years later, brought the fertility rate back up to 1.27 — higher than it had been in almost a decade.

These year-to-year fluctuations come with a host of problems. It makes population trends less predictable. The 2010 tiger drop was particularly alarming to Taiwanese authorities, projecting the future of their aging population. But it’s also bad for infrastructure. Public facilities, especially schools and other youth programs, often see a bulge in patronage one year and a drop-off the next. It causes problems for the kids, too: imagine the difficulty of getting into college, if you were born in the Year of the Dragon in a country with a strong dragon preference.

A Peculiar Phenomenon

The prevalence of this effect has baffled scholars for generations, as it seems to have only emerged within the last few decades — since around the 1970s — precisely as these countries have industrialized and the average family size within these countries has shrunk. Zodiacal superstition has only governed family planning since these countries have started to modernize.

One theory, put forth in The Influence of the Chinese Zodiac on Fertility in Hong Kong SAR, is that, before the 1970s, the dominant force in cultural Chinese families was the adage, “May good luck, long life and children, all be (yours) in plenty.” Families grew as large as they could for as long as they could, which left little room to preference one year over another. “Ideals of family size,” the researchers write, “and even the idea of family planning were largely outside the realm of conscious choice.”

But, they say, with modernization came the rise of contraceptive practice, and smaller families, and the notion of child quality. They write: “As couples plan for ever smaller families, prospective parents become more concerned with child quality and wish for a glorious future

for their offspring.” Zodiacal preferences are a manifestation of this concern for quality. Many parents go out of their way to have a child in an auspicious year in order to ensure he or she will have a lucky life.

It’s also worth noting that China itself does not appear to follow this trend at all. The researchers attribute this to state policies governing family size, and to the communist government’s strong stigmatization (and, in some cases, persecution) of superstition and religion, which were seen as capitalism and colonialism’s vestigial fetters:

China’s strict one-child family policy operated since 1979 might have made zodiacal birth timing highly impractical. In the circumstances, prospective parents have less concerns of the zodiac. Rather, they would be dominated more by the desire to have a child in any year allowed. […] During this early era, anything resembled older traditions was criticised, while everything new and revolutionary was lauded

China’s national fertility rate seems pretty indifferent to the zodiac; Priceonomics; Source:

Another piece of the puzzle might be that the phenomenon is in fact seen within certain subcultures of Chinese society, but drowned out by sheer size of the population. There are reports that this year, the Year of the Sheep, is being talked about in China as a particularly bad year for births.

Even though there’s no evidence that a stigma against people born under the sheep sign has influenced fertility rates in the past, the idea that people born in the year of the sheep are, “meek and destined for slaughter rather than success,” has become so widespread that the state has launched a media campaign combating the superstition. The campaign includes a list of famous people born under the sheep sign, including Thomas Edison, Steve Jobs and Rupert Murdoch.

The Tyranny of Widely-Held Superstitions

This isn’t all driven by parental superstition. In some cases, there are very pragmatic reasons to shoot for “lucky” zodiac signs, and to avoid “unlucky” ones, even if you don’t believe in astrology. This is mainly the case if large or important segments of society do believe in astrology, as seems to be the case in Taiwan. From Asia Times:

A baby born then could realistically be likelier to endure hardships later in life than others. Charlene Chang, public relations manager of the Taiwanese recruitment agency 1111, talks about the not-so-uncommon practice of selecting job aspirants according to their zodiacs. “Quite a few firms assign fortune tellers to page through job applications,” she says, and “before bosses hire, they want to know whether a newcomer is likely to become a friend or foe within the company.”

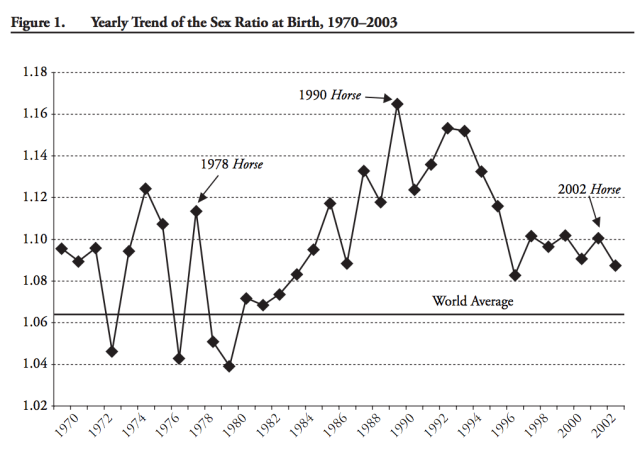

In non-Chinese societies which have similar astrological zodiacs, like South Korea, different signs carry different implications. The horse is considered a good sign for males but a bad sign for females in Korean culture, and the gender ratio of births in horse years skews male:

Source: Lee and Paik

Researchers studying the phenomenon say much of this is likely due to the state-discouraged practice of selectively aborting female fetuses. But researchers have also found evidence that at the beginning of the Year of the Horse, some parents intentionally misreported the birthdate of their daughter as earlier than it actually was. The gender ratio in the last month of Years of the Snake skews sharply female, and the gender ratio in the first month of Years of the Horse skews sharply male. This effect is less pronounced in recent cycles — probably partially because it’s gotten harder to lie, as the birth registration system has gotten better.

It might seem silly to those of us outside the culture, but Chinese astrology has very real demographic effects. And it doesn’t look like these effects are going to simply evaporate as the countries continue to economically develop. It’s a problem the members of future generations are going to have to address, dragons, tigers, and sheep alike.

This post was written by Rosie Cima; you can follow her on Twitter here. To get occasional notifications when we write blog posts, please sign up for our email list