On a rainy autumn afternoon in 2002, Will Vinton sat alone in a board room, reviewing his severance package.

His desk, now barren, had once displayed the emblems of a storied career: an Oscar, six prime-time Emmys, a slew of Clios and innumerable other honors. He had brought clay animation back to life. But his creations, once animated on silver screens, were now housed in cardboard boxes, frozen in various states of bewilderment.

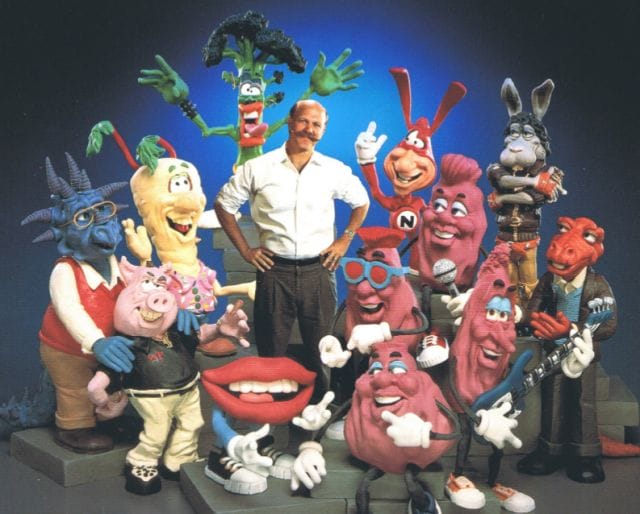

Over thirty years, Vinton had built his firm, Vinton Studios, into a $28-million-a-year enterprise. He’d produced, directed, and brought to life the most memorable characters of the 80s and 90s — the California Raisin, Thurgood Stubbs, the “Red and Yellow M&Ms.” He not only coined the term “claymation,” but was its unheralded king.

And now he was in the board room, tracing over the language that seized his kingdom. Hours earlier, he’d handed over his company and all of its trademarks to Nike co-founder Phil Knight. The billionaire’s son, an animation intern and ex-rapper with no management experience, would be assuming his place.

But thirty years earlier, long before the corporate chaos, Vinton picked up a ball of clay and saw a world of potential.

An Animated Architect

In 1966, 18-year-old Will Vinton threw a few things in a duffel bag and left his childhood home in McMinnville, Oregon for California. The son of a car dealer and a bookkeeper, he’d temporarily leave his humble roots behind to attend The University of California at Berkeley.

It was a wild time to be at Cal: the Free Speech Movement was undulating, Vietnam protesters occupied the corners of the city, and the Black Panthers had just emerged in neighboring Oakland; the campus was pulsating with energy — Vinton, a doe-eyed freshman, was in its thralls.

Inspired, Vinton had his father ship out the family’s 16-millimeter camera, and soon began documenting the local scene. His earliest films — Gone for a Better Deal and The First Ten Days — captured the rapture of Berkeley’s counter-culture.

At the same time, Vinton became infatuated with the organic, free-flowing work of Spanish architect Antoni Gaudí, and began pursuing a degree in architecture. “You really couldn’t emulate his buildings with T-squares and straight edges,” he tells us. “So I started to work with clay as a medium for creating structures.”

Before long the table in his apartment became a creative hub for clay experimentation:

“I’d get together a bunch of my architecture buddies and artist friends, and we’d sit at this table just covered in clay — there was clay everywhere — building stuff, and filming it. Guys would stop by the place and say, ‘Oh, this is cool! You should do something with this!’ I started thinking a little more seriously about where to take it.”

At the time, one of Vinton’s housemates was Bob Gardiner, a sculptor and student at California College of Arts and Crafts. Marrying Vinton’s editing skills and Gardiner’s sculpting prowess, the two created Culture Shock, which toyed with the use of clay as a viable animation medium. The film earned them first prize at the prestigious Berkeley Film Festival.

Two Dudes, a Basement, and an Oscar

After college, the pair parted ways for a while, and clay hit the back-burner. Gardiner, still a student, preferred to party; Vinton moved to Portland, Oregon, got married, and “settled down.” For a few years, Vinton honed his filmmaking skills, working as a freelance director, cinematographer, and sound technician on short films and documentaries. By 1973, with a full arsenal of production skills under his belt, he began reconsidering the potential of clay.

Vinton called Gardiner, who had just completed his degree in California, and talked him into moving to Portland to take part in a clay animation experiment. What ensued, says Vinton, was a sequence of events neither of them could’ve ever imagined.

“We started out just experimenting in the basement of my house. I was working full-time with freelance projects, and Bob would just be down there all day. We’d work on this concept on weekend, evenings — it kind of took over our lives.”

For a year and half, Gardiner lived in Vinton’s basement (eventually, Vinton’s wife kicked him out), relentlessly molding clay into odd characters that looked like something out of a bad acid trip. The result was Closed Mondays.

While clay animation had been around long before Closed Mondays (as early as 1908’s The Sculptor’s Welsh Rarebit Dream), it had been replaced by cel (hand-drawn) animation by the 1920s, and was castigated as impractical and time-consuming. Though clay continued to be sparsely used in subsequent animations (Gumby, in the 1950s/60s), Vinton revitalized — then proceeded to revolutionize — its applications in film.

Closed Mondays was incredibly laborious. As a stop-motion film, one frame shot was required for each tiny movement; in total, the eight-minute film used 11,520 single shots (doubling included), each of which required a slight re-sculpting of the clay. The man’s face — a life-size bust — was made from a plastic skull covered in plasticine; Vinton would gradually shift the contours of the face to alter expressions frame by frame.

At times, the character’s emotions verged on “the grotesque,” but the duo accepted their mistakes, errors, and mishaps as part of the process that made their film truly unique. For instance, after weeks of testing shots, they were having “a hell of a time” getting their clay character to walk without wobbling. To work around this, they made him inebriated. Vinton harps on the process:

“There were so many challenges with early claymation, production-wise. We were doing things that had never been done — POV shots, new rack focusing techniques — so we had to find our own solutions. The whole point was to challenge ourselves and try different things. If things went wrong, we’d flip them into positives.”

With high hopes, Vinton submitted his film to a local festival in Portland. It had taken him and Gardiner 14 months, hundreds of hours of editing, and thousands of hours sculpting — and within two minutes, the film was outright rejected. “The judge didn’t even screen it,” recalls Vinton. “It just wasn’t his cup of tea, or whatever.”

A Bolex Rex-5, the camera Vinton used to shoot Closed Mondays

The pair was crushed. On a whim, the deflated Vinton showed it to a friend who owned a small theatre in the city, and it was screened, as a favor, before a full-length film. The response was incredible.

With support, the film was submitted to film festivals — first small ones, then, “as a joke,” bigger ones. But the film rallied, taking the top prize at nearly one hundred showings internationally, including Cannes (the “creme de la creme” of festivals).

Then, as quickly as it was once rejected, the film went on to be nominated for an Academy Award for Best Animated Short…and it won. Not only was it the first stop-motion film to ever win in that category, but it claimed Portland’s first ever Oscar. Suddenly, 26-year-old Vinton was catapulted into the national spotlight. The award came with no monetary payoff, but offered him something much more valuable: credibility.

“After being completely rejected at a local level, we were validated. It’s exactly what I had set out to do — prove that clay animation was still viable. Back then, 99% of animation for for children and families, or two-dimensional; this was neither — it was for adults, it wasn’t a kiddie film. So many people told us it wasn’t going to happen, just forget it. We validated the medium, and it opened doors.”

And open doors, it did. Vinton was barraged with requests from advertising firms and film agencies to produce commercials and shorts. In the aftermath of their first film’s success, Vinton and Gardiner decided to go their separate ways (“Bob was incredibly talented, but his work ethic was non-existent,” says Vinton); with clients knocking on his door, Vinton embarked, alone, on his next journey.

The Rise of Vinton Studios

By 1974, Will Vinton’s clay animation had became both widespread and enormously popular, and he was the hottest commodity on the market for big brands looking to distinguish themselves.

His first project — a commercial for Rainier Beer — tasked him with creating a “full mountain scape complete with a bunch of animals singing the praises of beer.” Quickly, Vinton learned that commercial work was a viable way to make decent money: they were short, fun, and allowed him to do what he wanted to do.

What he wanted to do was create films, and he wasted no time. The Rainer commercial inspired his next project, 1976’s Mountain Music:

The film won first prize at the Hemisfilm International Film Festival, and prompted Vinton to expand his production team. He brought in six employees — most of whom were old architecture buddies and artists — and continued focusing on “seeing how far one could push clay animation.” The small team devoted themselves so much to this philosophy that they wouldn’t even entertain ideas that “seemed too easy;” the results were unbelievable.

Vinton Studios went on to produce three 27-minute fairy tales in rapid succession — Martin the Cobbler (1977), Rip Van Winkle (1978), and The Little Prince (1979) — all of which earned the team “bushels of awards.” Vinton, under the guidance of famed animator Barry Bruce, became a master of refining his characters: once jolting and awkward, his clay puppets were now “smooth, with finer contours, and richer detail.”

When the team produced a behind-the-scenes feature in 1978 documenting the clay animation process, Vinton coined the term “Claymation,” and trademarked it. The use of this term differentiated them from the vast, inevitable sea of imitators that had begun to surface.

Despite his success, Vinton’s firm earned just $5,000 in its first five years of operation — enough to sustain his work, but not to sustain a team. This would change in the 80s: Vinton Studios became omnipresent and profitable, playing a hand both in film and commercial work.

In 1985, Vinton secured a contract to produce stop-motion animations for Disney’s Return to Oz — the studio’s first ever outside job — and it opened doors for them as a “hired hand.” Vinton also produced his first full-length claymation film, The Adventures of Mark Twain, which contained probably one of the creepiest scenes in the history of cinema (though Vinton maintains the scene is “pulled so far out of context — that’s why Youtubers are saying, “Oh this is horrible!”)

By the end of the 1980s, Vinton had won a trio of Emmy Awards, and had been nominated for four Academy Awards. His projects took him everywhere from producing an animation sequence for Michael Jackson’s Moonwalker film to claymating Bruce Willis into a frog.

Vinton also continued his work in commercials, creating some of the most memorable spots of the decade. A widely-disseminated ad he made for Alka Seltzer starred a “convention of disgruntled stomachs” waiting for their hero to arrive; his “Noid” series for Dominoes Pizza featured a little red-suited man with antennas intent on destroying pizzas:

But perhaps most famous of all, his work for the California Raisin Advisory Board in 1986 featured a troupe of California Raisins singing Marvin Gaye’s “I Heard It Through the Grapevine” — a rendition that was so popular it landed on the Billboard Hot 100.

The clay raisins became an overnight sensation. They were soon the official mascots of Raisin Bran cereal; a whole bevy of collectible figurines was released, and CBS hired Vinton Studios to produce a musical short, Meet the Raisins!, which was aired on prime-time television and garnered nearly 100,000 per-release orders on VHS. If Vinton hadn’t been on anyone’s radar before these spots, he was now.

California Raisins’ success brought new wealth to the company: $3 million per year in revenue. Vinton’s team expanded to 50-60 people and he found himself gradually phasing out of the animation process and more into a business-oriented role. Keeping a staff of animators busy every day and overseeing their work was getting cumbersome, and the visionary began questioning his creative purpose in the company. Despite this, he forged onward.

Vinton Goes Digital

In the wake of the California Raisins craze, commercial advertising came to compromise over 50% of Vinton Studios’ business — but this was a double-edged sword. The raisin commercials had gotten so huge that claymation became synonymous with them; ad agencies that subsequently hired the firm wanted different mediums. Vinton had to think bigger.

Through the 80s, Computer-generated imagery (CGI) technology had been snaking its way into film and television. In 1991, the new technology had a banner year with two major box office hits — James Cameron’s Terminator 2, and Disney’s Beauty and the Beast — both of which made substantial use of CGI. Increasingly, animation houses turned to computers.

Vinton decided to go all-in.

Over the next few years, he hired a team of 20 CGI animators, built a computer department, and began integrating the technology into his commercial work. It was a difficult time: Vinton had to lay off some of the staff to make room for the CGI division, and he had to balance the creative demands of his remaining artists with the technical aspects of the new processes:

“Computer animation was not art friendly — anyone with a right half of a brain can do it; CGI requires an animator to be a technician more than an artist. But I found that my old stop-motion animators were best at adapting to it. CGI works in 3d space, and they already had the knowledge of the process in their bag of tricks.”

The team’s first task was a commercial for Chips Ahoy! The 30-second spot took 60 days to produce, but was ground-breaking: instead of abandoning claymation altogether, Vinton integrated it with old-school stop-motion techniques and CGI to create incredibly unique visuals. The commercial caught the attention of M&Ms/Mars, and paved the way for one of Vinton’s most recognizable characters, the “Red and Yellow” M&Ms; for the next ten years, Vinton Studios would be the M&Ms’ sole animator.

Then, several things happened that changed Vinton Studios forever.

In an odd twist, Eddie Murphy hired them to animate his prime-time television series. The PJs, which would use both stop motion and CGI technology, gave the firm “a chance to give drab technology a personality.” But since the clay process took too long for a weekly format, Vinton pioneered yet another medium, “Foamation,” a system in which ball-and-socket armatures were coated with foam latex. The characters were sturdier and lighter than clay, and were easier to move.

Soon after, the firm signed on another stop-motion series, Gary and Mike, for UPN.

By the late 90s, Vinton Studios had reached its apogee in revenues, at $28 million. But the success was deceiving: they were entering a new market, faced much larger projects than they were used to, and funding a rapidly growing team. Pixar’s 1995 smash hit Toy Story only further fueled the studio’s grand ambition of becoming a major motion picture house. They’d need more money.

Courting Phil Knight

With the promise of a major television series, and a transition into the digital market, Vinton had to convert his studio into a full-fledged business. His first move was to hire the company’s first professional CEO, Tom Turpin, a Hollywood executive who’d previously been “Richard Branson’s media hand” at Virgin Entertainment.

The PJs, along with Gary and Mike, put tremendous stress on the studio to grow; in a few months, the team quadrupled from 100 people to over 400. To fund this expansion, Turpin was tasked with bringing in outside investors, with a target of $5 million.

Coincidentally, Vinton Studios’ legal counsel, Brian Booth, was also Nike’s; when he heard Turpin was looking for “a big fish,” he suggested multi-billionaire Nike co-founder Phil Knight. “There aren’t many things he’s comfortable investing in,” the lawyer told Turpin, “but I think he’d really like this.”

Booth was right: while touring Vinton Studios, Knight turned to Turpin, smiled, and said, “This reminds me of when Nike was small.” Initially, the titan agreed to pitch in $2-3 million; when another investor bowed out on the remaining $2 million investment, Turpin found himself asking Knight a for more.

“We’re on death’s door, Phil,” he told the Nike chairman. “Will you save us?”

“I liked it for $3 million,” responded Knight. “And I like it for $5 million.” With that, Knight fronted the full funding round, and assumed a 15% stake in the company. An additional $2 million was chipped in by venture capitalists, and Vinton Studios suddenly had $7 million in the bank.

“Chilly Tee:” From Intern to Board Member in Three Years

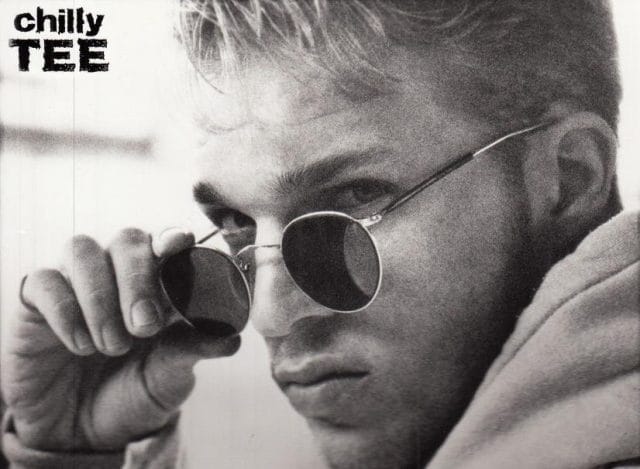

As Vinton Studios was transitioning into computer animation in the early 90s, a young rapper named “Chilly Tee” struggled to cut it in the inhospitable streets of Portland.

“People think I’m tryna front, tryna fake, tryna be black — but I ‘aint,” the lyricist told The Word in 1994. “I’m a black sheep in the industry, if you will. Listen to my track ‘Krisis of Identity — you’ll get it.’” Chilly’s “krisis” was clear: he was trying his darndest to get street cred, but had to “cope” with his roots as .001-percenter.

You see, Chilly Tee was really Travis Knight, the son of Nike’s billionaire co-founder (and Will Vinton’s newest investor).

When Chilly showed an interest in dropping beats, his father built him a state-of-the-art recording studio in a backroom of his mansion. When Chilly found himself without a “posse,” his father hired The Bomb Squad — one of the best rap production crews in the industry — to flank his homeboy. And finally, when Chilly failed to generate an inkling of interest from record companies, his father courted a deal with MCA, using his connections in the entertainment industry.

The rapper moved to New York, holed up in his parents’ Manhattan penthouse for six months and, in 1993, cut his one (and only) album, Get Off Mine, a glorious ode to “just doing my thing.” Hank Shocklee, the Bomb Squad member who produced the album, later expressed his faith in the project to Vibe Magazine:

“Anybody can sit there with somebody who has talent. Here’s a situation where you have to create the whole ball of wax. If you can get this kid across, you can get anybody across.”

His father’s return on investment came in the form of product placement. “Just Do It,” a track from the album, unabashedly paid homage to Nike: “Just do it, you gotta just do it.“ But even Phil Knight couldn’t save his son’s rapping career, and the album was a major flop. In the end, the only award Chilly won was a spot on Complex’s 120 Worst Rapper Names of All Time list.

Slowly, Chilly transitioned into “real life” while continuing to pursue his dream. In 1998, at age 25, he graduated from Portland State University with no job experience and few prospects.

When Phil Knight came on as an investor in 1998, he had a request. Tom Turpin, Vinton’s CEO, recalls:

“Phil approached us and said, ‘Hey, my son’s trying to be a rapper. I don’t know if you have any spots, but would you be willing to give him a shot?’ Of course, we welcomed Travis; he was a low key, unassuming guy — and how can you say no to Phil Knight?”

With no knowledge of animation, Travis Knight was assigned “mop duty” — he started out in the doldrums of the CGI department, rendering whiskers on The PJs’ Thurgood Stubbs. Nobody at Vinton Studios knew he was the heir to a man worth $9 billion ($16.3 billion today) — a man who’d just purchased 15% of the company.

And nobody knew that in three years’ time, the kid would be sitting on the studio’s board of directors — or that, in less than a decade, he’d be its president and CEO.

![]()

In January 1999, riding on a massive effort by Vinton Studios, The PJs debuted on Fox. Each of the 43 episodes Vinton Studios produced had taken over two months, and the top-heavy show ultimately cost more than its ratings justified. Just three seasons later, in 2001, the show was discontinued.

The same year, the company took another blow: Gary and Mike, the show the studio had secured with UPN, was also cancelled, after only one season. Despite winning a combined three Emmy Awards, Vinton’s two hopes for the future had both been cut short. As if that weren’t enough, the studio’s commercial division took huge hit when the September 11th terrorist attacks led to an industry-wide downturn in advertising.

Some questionable choices by management (like opening a full-floor penthouse studio in Los Angeles, pouring money into it, leaving it unoccupied, and watching it fold only six months later) put extra strain on the company, and it entered a period of intense financial duress. Vinton recalls feeling lost in all of this:

“It was getting out of my control. There were LA-type agents and executives brought it, contracts that were really deep — money was spent on things that weren’t adding any real value. For the first time in twenty-five years, our studio was losing money. I started looking for a way out; I wasn’t happy anymore.”

Turpin was dismissed and Jeff Farnath, previously an executive at Disney, stepped in to assume his post as CEO. “He was a great guy,” says Vinton, “but didn’t really understand the business. He had culture shock.” As disney executive, Farnath was used to security and big budgets — a far cry from the ailing Vinton Studios.

As investors, board members, and businessmen took over operations, company culture suffered. “Max” [name changed], who had joined Vinton Studios as an animator in the late 1980s, left on a sabbatical in late 2000; when he returned seven months later, he saw a completely different company:

“When I left, we had this very close team. There was a lot of trust, we shared secrets, everybody got a chance to do many different things — it was like an art colony, with free exchange of ideas, and no competition. When I came back, the change was remarkable: the atmosphere was stern, corporate — it was an entirely different company with an entirely different attitude.”

Massive layoffs ensued: the team Vinton had ramped up for the series was cut back down from 400 to less than 100. Max, who’d been there for fourteen years, was offered a severance package; others weren’t so lucky. “People were offered funny deals, and given much less than they were supposed to get,” he adds. “There were last-minute changes in contracts and severance package rules. People weren’t treated well.”

![]()

In the course of two years, a severely mismanaged Vinton Studios blew through more than $7 million in funding, largely due to their unwillingness to scale back the team even more. There was only one hope to salvage the company, and it came with a swoosh.

Farnath, Vinton Studios’ new CEO, approached Phil Knight “with his tail between his legs,” and asked the businessman to put in more money — just a few years after Knight had put up $5 million. This time, Knight had leverage to be a controlling shareholder.

“If I’m gonna put my money into a hemorrhaging company, I’m gonna own it,” Knight told Farnath. With a second investment, he swiftly assumed control of the board, and appointed Nike veterans to join him. Ownership secured, his next plan of action was to give his son a seat at the table.

In late 2003, Travis Knight was promoted to the board of directors. With only a few years of production experience under his belt, “Chilly Tee” was now Will Vinton’s boss. In his time as an animator, Knight had actually become astonishingly good — one of the best in the business — but by all accounts, he didn’t qualify to operate a company. Just six months later, citing “mounting pressure” from Phil Knight, Will Vinton stepped down from the board and was fired from his office position.

Two years earlier, Vinton’s stock had been worth $20 million; now, he sat alone in a cold board room, with a $125,000 severance package in front of him. “I was devastated,” recalls Vinton. “Devastated.”

He took Phil Knight to court, suing him on the grounds he’d been unfairly ousted. The whole thing had been part of a grand scheme, he claimed, for Knight to give his kid a company. His charge of corporate nepotism wasn’t unsubstantiated — Knight had no reservations in admitting he’d acquired the company with his son in mind. But the case was dismissed, and the Knights proceeded to strip and reconstruct Vinton Studios into an entirely different company.

In the severance process, Knight also took ownership of Vinton’s life-long body of work: the M&Ms, the California Raisins — even the legal trademark rights to the term “Claymation.”

Will Vinton, once the king of clay, had been dethroned.

Laika: Chilly Goes to Hollywood

In the years following Vinton’s departure, Phil Knight poured $180 million of his own money into the shell of Vinton Studios and rebranded the firm as Laika. With his son by his side, he set his sights on big-budget, major motion pictures.

Using his clout, Knight lured in animation veterans from Disney, DreamWorks, and Pixar. He cleared house and brought in a troupe of Nike executives with no discernable experience in film (one hire even told Fast Company that he “wouldn’t know Finding Nemo if it hit [him] in the face”). Henry Selick (a storied producer who’d directed The Nightmare Before Christmas) was hired after Travis had cited him as an animation hero.

Knight commissioned a sprawling $55 million campus to be built by the same architect he’d used for the Nike headquarters, complete with a 300-seat movie theatre and state-of -the-art workout facility. His investments in the studio’s projects were equally grand: the company’s first feature-length film, Coraline, enlisted $50 million of the investor’s money.

In 2009, Coraline debuted. The film was a hit: with a total budget of $60 million, it grossed $124.6, and was nominated for an Academy Award. The team followed this success with ParaNorman in 2012, which grossed $107.2 million on the same budget. Boxtrolls, their next featured film, is due this September and looks to break nine-figures.

But the studio’s journey hasn’t been smooth sailing: in 2008, they ran into the same problem Vinton Studios had: a planned animated featured fell through, and they had to cut “a significant portion” of their staff. In 2009, following Coraline’s success, the company severely downsized again to focus solely on stop-motion.

“Max,” an animator who’d been laid off from Vinton Studios, later became a freelancer and found himself back at Laika to work on Coraline. “It was a wonderful project to be involved in,” he says, “but I’ve had better experiences.” He’d been excited to work with Selick, one of his heroes, but found that animators were treated poorly by management. “There was a ‘Just Do It’ attitude. It was a beautiful experience, but rough for a lot of people.”

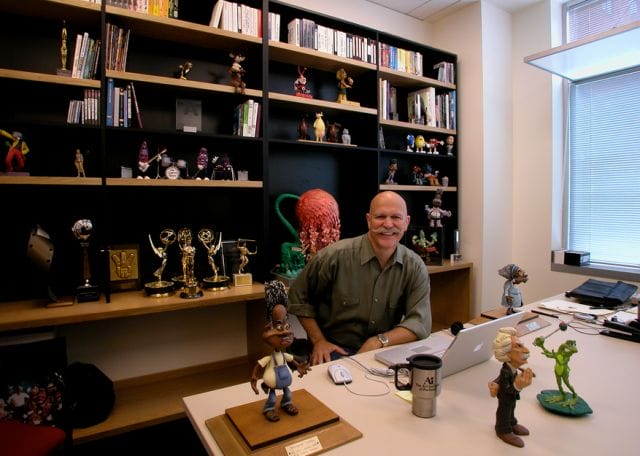

Promoted to CEO and President of Laika in 2009, Travis Knight is at the company’s helm today. When film critic Bill Desowitz asked new new chief how he felt shortly after his appointment, he responded with a new breed of confidence.

“It’s an interesting transition, as I’ve gone over the different permutations and roles in the studio over the years,” Knight told him. “So who better than me?”

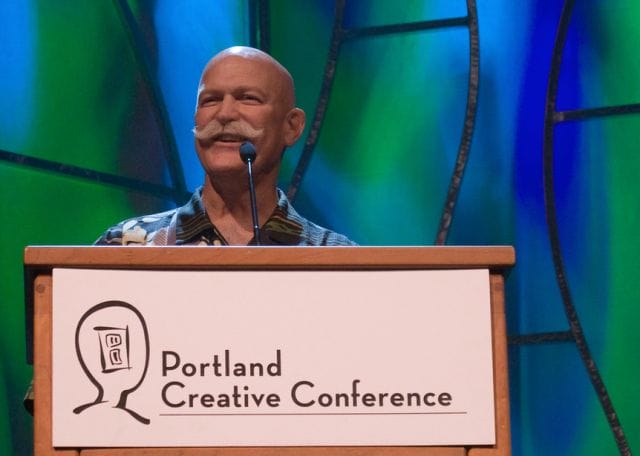

Free Will

With the manicured mustache of Mark Twain and the chrome dome of an M&M, the 66-year-old Will Vinton looks almost like an aged, real-life rendering of his own creations.

Today, life isn’t as grand for him as it once was — though it’s simpler, quieter, and more hands-on. He’s stepped away from the “cesspool” of business and gotten back to what matters most to him: the beauty of animation.

After being ousted in 2002, Vinton endured a period of financial and psychological anguish. The modest fortune he built for his family over 30 years had largely been wrapped up in company stock; when the ship went down, he sank with it. He sold his Oak Grove home of eight years, pulled his two sons out of private school, and “scaled back” on the lifestyle he’d grown accustomed to.

“There was definitely a time when I was rolling the dice and growing the company,” Vinton told the Portland Tribune in 2005. “I didn’t think the downside would be as big as it was.” Months after the interview, Vinton was knocked down again: Bob Gardiner, with whom Vinton had sparked his career and won an Academy Award, committed suicide.

Vinton has tried to put the past behind him. Now, he’s back where he began: getting his hands dirty and dreaming up the impossible.

Now wary of investors, Vinton has since turned to Kickstarter to fund his most recent endeavor — “The Kiss,” a Broadway musical about a lowly frog who dreamt big — but raised just 20% of his $80,000 target. He also teaches animation classes at the Portland Institute of Art, and operates Freewill, a “boutique animated movie and licensing studio.” Several projects are in the works, he tells us, including Santa: An Animated Holiday Treat, which tells a tale eerily similar to his own: “Santa must battle his megalomaniacal nemesis Old Man Winter to reassert the worth of his old-fashioned ideals in the face of a modern world.”

But modernity hasn’t deterred Vinton from dabbling in his old medium: he still holds clay in high esteem.

Vinton tells me about a recent trip he took to Seoul, Korea, to visit a small production studio. In a corner of the office, a small team of animators gathered, played Closed Mondays frame by frame, and studied Vinton’s work with crime-scene scrutiny. He spent several hours in the firm’s office, watching his characters flirt across the screen, each a vignette, a moment in time. A modern-day Prometheus, Vinton had made clay human. He had brought it to life, made it dance, and cry, and sing.

And like the clay, he was constantly altered. Like the clay, he shrunk under fire, but came out more colorful than before. Twisted, pulled, and reshaped, he emerged with an animated smile, as if finally realizing what it is he accomplished.

Will Vinton made characters out of clay, and clay made a character out of him.

This post was written by Zachary Crockett. Follow him on Twitter here, or Google Plus here.