“He’s a lumberjack, and he’s [NOT] okay.”

~ “Lumberjack Song,” Monty Python

At the tail end of last year, the term “lumbersexual” — referring to a new wave of bearded, flannel-clad hipsters — went viral. “He looks like a man of the woods, but works at The Nerdery, programming for a healthy salary and benefits,” wrote Gear Junkie. “His backpack carries a MacBook Air, but looks like it should carry a lumberjack’s axe.”

While the logger has been fetishized by aspiring fashionistas, the reality of his trade is much grimmer.

Take, for instance, the fate of 21-year-old logger Tyler Bryan. At around noon on February 10th, 2014, he was standing at the base of a steep slope in Morton, Washington; just above him, rigged to a steel skyline cable suspended above the ground, a 4,000-pound log with a diameter roughly the size of a monster truck tire slowly made its ascent.

What happened next occurred quickly, and without warning: The cable, over-burdened by the weight of the load, sagged. The log spun out of control. Bryan, whose first son was due in two months, never saw it coming.

In the aftermath of his death, a fundraiser was set up to gather funeral donations. Dozens of commenters, each with his or her own logging tragedy to relate, came to sympathize:

“I lost my brother and a friend in two separate logging accidents 24 years ago. They both left behind new brides and unborn children, just as what happened here…”

“I lost an uncle, my brother, and almost my son two weeks ago in the logging world. Such a dangerous job…”

“I am a daughter of a logger and lost my father to a logging accident in 1980…”

“I own a logging company and live in fear daily for all my guys, their wives and their children. I feel terrible for everyone involved…”

These stories are only a small visage into what is, statistically, America’s deadliest career path.

***

Since 1992, the the federal government’s Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) has kept data on work-related deaths and injuries. Over a 22-year year span, an average of 5,650 U.S. workers perish each year on the job, or due to injuries procured on the job. In general, thanks to the implementation of stricter safety regulations, these fatalities are on a slow, gradual decline:

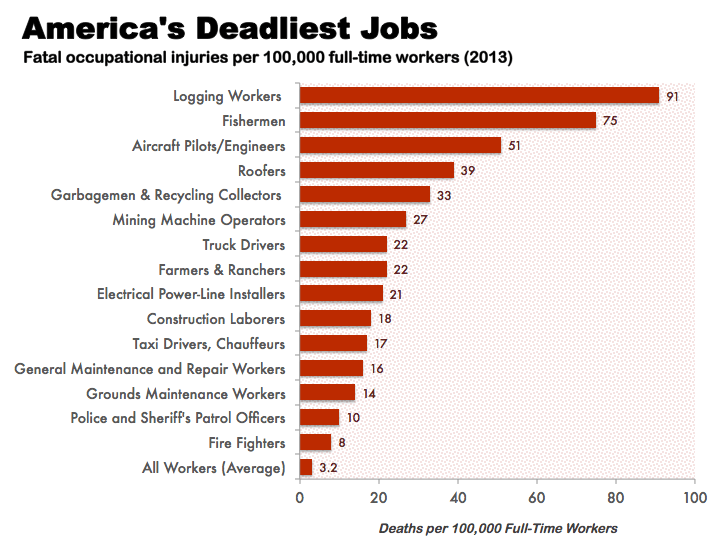

But the BLS also breaks these deaths down by profession — and upon closer inspection, certain jobs are still astronomically dangerous. We went through the most recent BLS data set (2013), and ranked the jobs with the highest death rates per 100,000 workers. Out of hundreds of jobs, loggers are the most statistically likely to die due to work-related injuries:

Note: Interestingly, the three most deadly jobs are all instances of man versus nature: logging (trees), fishing (the sea), and aircraft pilots (air); also, while women and men shared an equal split in hours worked, 93% of all work fatalities were incurred by men

Taking into account the sum totals of all of the professions represented in the BLS report, the average American worker has a work-related fatality rate of 3.2 in 100,000. For the United States’ 60,000 logging employees, this figure is 91 in 100,000 — nearly 30 times greater than the average job.

Despite the high-risk nature of their profession, loggers receive a median pay of only $33,630 per year, or $16.17 per hour. (In fact, with the exception of pilots, police officers, and firemen, every job on this list has a median pay of less than $45,000.)

These figures only represent the year 2013 — though a look back at all of the BLS data from 1992-2013 yields that lumberjacks still have the highest job-related fatality rate, with an average of 99 deaths per 100,000 workers. Fishermen and aircraft pilots retain the second and third spots, with 90 and 72, respectively.

The BLS explicitly excludes military jobs from its data, though we were curious to see how lumberjacks compared. Using the U.S. Government-maintained Defense Casualty Analysis System, which recorded both total full-time military members and the number of deaths from 1980 to 2010, we calculated an occupational fatality rate of 83 in 100,000 employees during that time period — still less than that of lumberjacks.

Note: Logging data compiled from BLS data (1992-2013); U.S. Military data compiled from the Defense Casualty Analysis System (1980-2010). It should be noted that soldier fatality rates greatly vary. During World Wars I & II, or Vietnam, these rates would be astronomically higher. Additionally, these figures account for all active duty military; if we were to break that down into specific job titles, it is likely that certain fields — say explosive ordinance disposal — would have much higher rates.

Despite a substantial decline in the deaths of loggers, it’s clear that they still face higher fatality rates than any other job (at least, those included in the BLS data). But why?

Why Is Logging so Particularly Deadly?

Shortly after Tyler Bryan was killed by an unsecured log, his mother spoke to a local reporter: “I kind of think he knew it was his time,” she said. “He knew the dangers, and we knew the dangers.” For people in the logging business, it is well understood that risk has always inherently been part of the job.

Ever since settlers arrived in Jamestown — a land of “goodly tall trees” — in 1607, Americans have been logging. By 1790, New England was exporting more than 36 million feet of lumber; between 1830 and 1890, wood accounted for more than 90% of the nation’s energy, and the state of Maine alone produced some 8.7 trillion feet of timber. Even with the onset of the Industrial Revolution, wood was enlisted to construct railway cars and mining structures, and was in high demand from cabin-building settlers expanding Westward.

Lumberjacks with a giant redwood tree, c.early 1900s (note the massive handsaw)

With few safety regulations and a free-for-all mentality, the logging trade was incredibly dangerous. In a September 1894 account in Munsey’s Magazine, a lumberjack speaks to this:

“Lumber camp life is by no means a desirable existence. Not only is it a dull routine of toil, but oftentimes it involves great hardship, while its pleasures are few and far between. A lake captain, who in his younger days spent several years in the woods, one day remarked that if he had his choice between spending three months in a lumber camp and the same amount of time in jail, he would unhesitatingly choose the latter…

[It is] a life fraught with many dangers. Falling trees and rolling logs have caused a long list of deaths; and it is on this account that the woodsman’s outer garments are of the brightest colors, blue, green, red, and yellow being the more prominent. The men are thereby able to see one another more distinctly through the thick underbrush, and by a timely warning to avert a great many dangers.”

In 1906, at the peak of the lumber business, there were 500,000 lumberjacks across the country. Living in “primitive” conditions, these loggers extolled the virtues of dangerous tasks, and were praised for being reckless and aggressive. Living in isolated logging camps, they built a “traditional culture that celebrated strength, masculinity, confrontation with danger, and resistance to modernization.”

Nonetheless, logging technology was soon embraced: hand saws were replaced by circular and band saws, and, by the late 1940s, the portable chainsaw. With the invention of the “feller buncher” (a large machine capable of cutting and lifting trees) in 1968, loggers could clear 200 trees per hour — a job that would’ve previously required the work of 20 men.

Today, large machinery is used for almost all logging — but it has come with its own set of dangers. From 1991 to 1993, OSHA investigated a series of on-the-job injuries, and found that fatal logging accidents were often the result of technology. Below are two such incidents:

Case Study 1: On October 9, 1992, a 33-year-old male tree feller was killed while operating a chainsaw. Using a 4-horsepower, 16-inch, bow-bar chainsaw, the victim felled a 40-foot pine tree. He then used the bow-bar chainsaw to cut the limbs from the felled tree. As the victim cut through a spring pole, the chain saw recoiled and kicked back, fatally striking him in the throat.

Case Study 2: On April 8, 1993, a 28-year-old male equipment operator was killed when he was struck and run over by the skidder machine he was operating. The victim pulled into a landing area (which had a slope of less than 5 percent), stopped the skidder, and unhooked a number of logs that were being dragged. The victim remounted the skidder and drove it around an idled log-loader. As he did so, the skidder ran over two logs lying on the ground—one 6 inches in diameter and the other about 14 inches in diameter. When the skidder ran over the logs, the victim apparently lost his balance, fell or jumped from the skidder cab, and was run over by the left rear tire. The victim sustained multiple traumas to the head and torso and died at the scene.

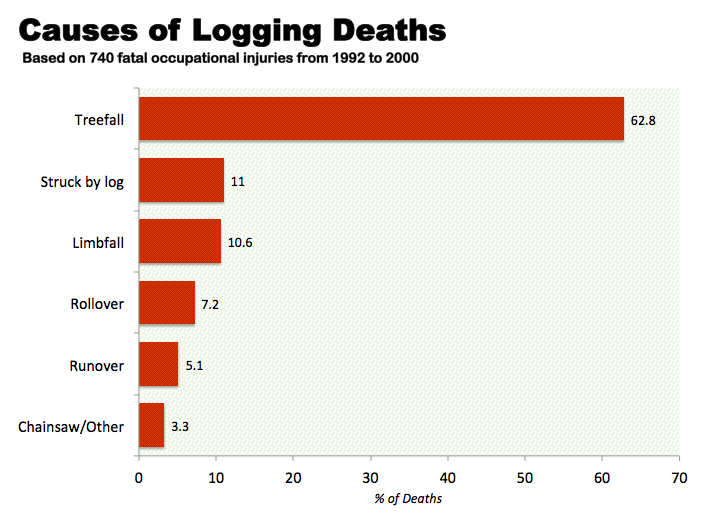

Still, falling trees account for the vast majority of logging deaths. In a 2003 study, the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health examined 780 logging deaths between 1992-2000, and found that only 15.6% of fatalities were the result of machinery. The remainder — a whopping 84.4% — were due to falling trees or rolling logs:

The OSHA study (mentioned above) also contains case studies of some of these cases:

Case Study 3: On December 3, 1992, a 24-year-old male timber cutter was fatally struck on the head while felling an 80- to 90-foot poplar tree. As the poplar fell, one of its limbs struck a 35-foot snag. The snag broke off about 4 feet above the ground, fell back toward the victim (who was looking in the opposite direction), and struck him on the head. Although the victim was wearing approved head protection, the blow was immediately fatal, as it fractured the first vertebra in his neck.

Case Study 4: On March 22, 1993, a 51-year-old male foreman and skidder operator was fatally struck on the head by a falling tree while he was cutting another tree into logs (bucking). A coworker was felling a 58-foot poplar tree about 50 feet away from the victim. As the tree fell toward the victim, the timber cutter and another worker shouted warnings. However, the victim (who was wearing a protective helmet and earplugs) apparently did not hear them. He was struck on the head and died instantly.

“One of the biggest dangers is that the logger can’t see broken tops of trees or limbs hidden by live branches,” says Dana Hinkley, who runs a logging safety program. Often buried in the canopy, these broken tree tops so commonly kill loggers that they’ve been coined “widow makers.”

While safety precautions have dramatically increased since the rogue days of 1900s lumberjacks, a macho attitude still pervades the trade. “They think they know how to cut trees because grandpa taught them how to do it,” says Hinkley, “and that good ol’ boy attitude keeps them from training.”

***

Increasingly, loggers are exploring more advanced machines as a way to improve efficiency and reduce workplace injuries. On its site, Associated Oregon Loggers lists an impressive array of technologies being implemented — from computer-optimized log cutters, to radio-controlled, remote mechanical operation. Tech-savvy loggers have even pioneered smartphone apps and data analytics systems.

But regardless of technological advancements, logging is intrinsically risky. In one way or another, workers must deal with some of nature’s largest creations, and as we know well, nature often can’t be tamed without dire consequences.

This post was written by Zachary Crockett. You can follow him on Twitter here.

To get occasional notifications when we write blog posts, please sign up for our email list.