This post is adapted from the blog of Flexport, a Priceonomics customer. Does your company have interesting data or insights? Become a Priceonomics customer.

Photo by Roger W

*****

It was not the first time that the Panama Canal had been overshadowed.

When the canal opened in 1914, it marked the completion of a project of Biblical proportions. The canal’s designers had created the world’s largest man-made lake by building the world’s largest dam. The decades-long construction project had claimed tens of thousands of lives, led to the creation of the state of Panama, and cost over $600 million—the equivalent of $14 billion today.

Yet the onset of World War I cancelled the grand plans imagined for the ribbon cutting. When the SS Ancon, a humble passenger ship, made the first official transit through the canal, the 200 dignitaries onboard did not include any heads of state.

“So quietly did she pursue her way,” wrote one witness on the Ancon, “that a strange observer coming suddenly upon the scene would have thought that the canal had always been in operation.” An ongoing battle between French, British, and German troops dominated headlines. Newspapers relegated the Panama Canal opening to the back pages.

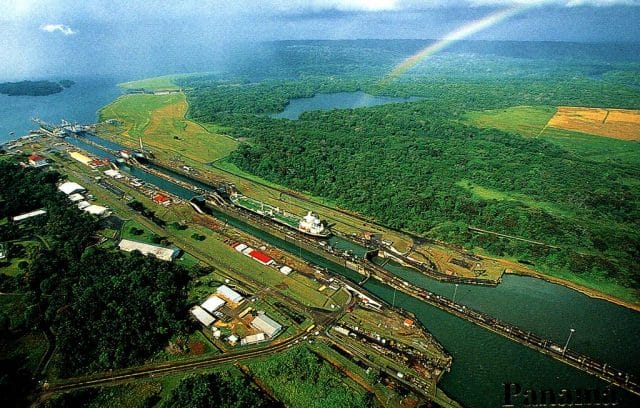

A century later, in 2005, the canal risked being overshadowed for another reason. The Panama Canal, the largest construction project in history, which had literally moved mountains to link the world’s oceans, had become too small. An increasing number of container ships, tankers, battleships, and even cruise ships no longer fit through the canal. Their hulls were too wide.

Map provided by davecito

The canal’s administrators and Panamanian politicians responded with a $5.25 billion plan to expand the canal. “The Panama Canal route is facing competition,” President Martin Torrijos, who needed to sell the plan to voters, told the press. “If we do not meet the challenge to continue to give a competitive service, other routes will emerge that will replace ours.”

Panamanians approved the expansion in a referendum, and a coalition of international financiers and construction companies assembled. The expanded lane is scheduled to open in April 2016.

Analysts still debate how the expansion will affect world trade. But if the global flurry of construction and speculation is any indication, the expansion seems to have succeeded in placing Panama back in the center of global trade.

The Path Between the Seas

The history of the Panama Canal reads like a lost account of the building of Egypt’s pyramids.

In the late 1800s, it felt like the canal was destiny. Europeans had dreamt of building a canal in Panama since early explorers failed to find a water passage to the Indies. During the California Gold Rush, the Panama Rail Road Company became the most highly valued company on the New York Stock Exchange. Prospectors sailed to Panama, rode the railroad to the Pacific, and caught ships headed to San Francisco. In the 1860s, a French company built the Suez Canal, which linked the Red and Mediterranean Seas, in Egypt. A decade later, a French company backed by its government and $400 million in capital began work on a Panama canal.

The possibilities were alluring: The 51-mile route would shave nearly 8,000 miles off the journey between the coasts of North America.

But the result was a disaster. Scientists did not yet understand the causes of yellow fever and malaria, which killed twenty-thousand workers and engineers. The company abandoned the project, and scandal rocked France, where politicians had accepted bribes to keep quiet about the company’s struggles even as they encouraged families to invest for the glory of France.

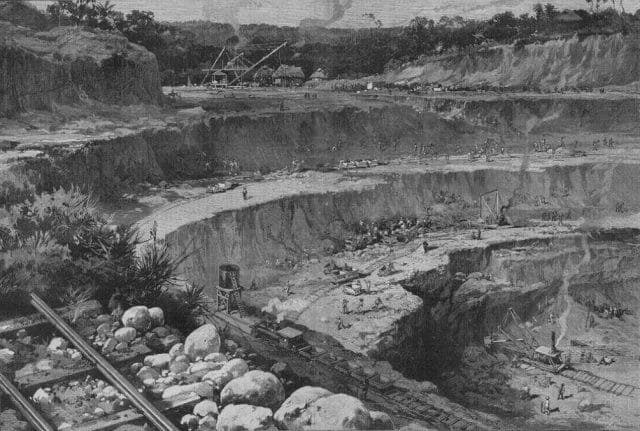

“The Panama Canal — The Great Culebra Cut” by Charles Graham. A reproduction published in Harper’s Weekly showing digging in the canal zone.

Then Manifest Destiny took over. America bought out the French canal project for $40 million—more than American presidents spent on the Louisiana Purchase and Alaska combined. When Colombia, of which Panama was then part, rejected a treaty that would give America sovereignty over the canal in perpetuity, President Roosevelt sent the USS Nashville to support Panamanian separatists as they declared independence and offered Roosevelt the canal zone on the terms he sought.

After an American company started digging with results as disastrous as the French effort, two changes save the project. First, the engineers gave up on digging a sea-level canal. Instead they planned a “bridge of water”: a series of enormous locks that would raise and lower ships 85 feet. Second, they realized the importance of health and battling disease. The efforts, directed by a doctor with experience fighting yellow fever, transformed the canal zone. As PBS reported:

Workers drained swamps, swept drainage ditches, paved roads and installed plumbing. They sprayed pesticides by the ton. Entire towns rose from the jungle, complete with housing, schools, churches, commissaries, and social halls.

Still, the canal made progress thanks to its disregard for human life. No amount of hazard pay could convince engineers to stay more than one year, so Roosevelt called on the Army Corps of Engineers—men who, Roosevelt said, “will stay on the job until…I say they may abandon it.”

Some 6,500 men died, and workers called one area, which was prone to rockslides, “Hell’s Gorge.” Most of the workers came from Caribbean Islands, and as Matthew Perry, author of a book about the canal, writes, “The working conditions were described by one as ‘some sort of semi-slavery’ and, under the Americans, there was a rigid apartheid system in place throughout the canal zone.”

In hindsight, it seems fitting that the celebration of the canal’s opening was muted.

The World’s Standard

In his history of the building of the canal, David McCullough notes that the project was remarkably free of corruption, graft, and delay. The canal opened six months ahead of schedule, which cruelly meant that it opened during World War I, when world trade was down.

The canal was profitable, but only an average of 5 ships a day transited the canal during its earliest years. Its first busy day fulfilled American national security interests rather than the canal’s founding vision of connecting nations: 33 ships of the U.S. Navy sailed from the Atlantic to the Pacific in July 1919.

Photo from “The Book of History: A History of All Nations from the Earliest Times to the Present, Volume XV” via Wikipedia

That changed after World War II. Traffic doubled from seven thousand ships a year to 14,000, and in 1966, workers installed lights that allowed ships to navigate the channel 24 hours a day. The canal only avoided lines as long as a San Francisco brunch spot by implementing a reservation system that books months in advance. American battleships and aircraft carriers and, in 1972, the Tokyo Bay, the then-largest container ship in the world, all squeezed through the canal with almost no room to spare.

That was by design. Canal administrators began debating an expansion of the Panama Canal as early as the 1930s—a desire driven mostly by the American Navy’s plans for battleships too large to fit through the canal. But the expansion never happened, so the Navy never built its massive ships.

Instead the maximum sized ships that can navigate the Panama Canal became a global standard: the Panamax. Until 1988, the largest container ships were all Panamaxes, and through World War II, the U.S. Navy built its ships to the Panamax standard. Its Essex class aircraft carriers—built from 1941 to 1950—had deck-edge elevators that folded up to fit through the canal.

Panamax also became a standard for ports, which designed their harbors to fit ships no larger than a Panamax. This not only shaped the size of docks and the depth of the harbor, but the height of bridges over rivers, the size of the cranes used to unload containers, and the capacity of cargo that ports prepared to handle.

By the early 2000s, however, as Panama debated whether to expand the canal, the Panama Canal looked less like a bottleneck that dictated the terms of world trade and more like a bottleneck that shippers were determined to avoid.

The canal had fallen victim to an innovation that had enriched it for decades: the shipping container.

Shipping containers are just steel or aluminum boxes full of cargo like clothes, tires, and couches, but they accelerated global trade in a way not seen since the adoption of the steam engine. In 1956, the first ship loaded with containers sailed from Newark to Houston. Normally the ship would spend days in port as hundreds of longshoremen moved cargo from the ship to trucks; instead a crane lifted the containers directly from the ship and onto trucks in a few hours.

Full adoption took decades. Once containerization became standard, however, we suddenly lived in a world where—as Marc Levinson writes in The Box: How the Shipping Container Made the World Smaller and the World Economy Bigger—it was “routine for shoppers to find Brazilian shoes and Mexican vacuum cleaners in stores in the middle of Kansas.”

The box was a boon to the canal, which gradually transitioned from American to Panamanian control beginning in 1977. The increase in trade, however, eventually made it sensible to build container ships larger than the Panamax. In the commodified shipping business, chasing economies of scale was the only way to profit.

In 1988, the first Post Panamax ship—which did not fit through the Panama Canal—left port. It held 4,000-5,000 twenty-foot shipping containers or their equivalent (TEUs) compared to a Panamax’s 3,000-4,500 TEUs.

Even bigger ships followed. A Post Panamax Plus, which debuted in 2000, can hold up to 8,000 TEUs. The first Triple E, which can hold as much cargo as six Panamaxes, made its inaugural trip in 2013.

Many of the Post Panamax ships serve routes like China to Western Europe, which pass through the larger Suez Canal. Others transport cargo from Asia to the East Coast, and would in the past have used the Panama Canal.

These Post Panamax ships follow one of two routes that bypass Panama. Some sail east from Asia, through Egypt’s Suez Canal, and across the Atlantic. Others sail across the Pacific Ocean to ports on the West Coast. From there, American or Canadian railroads transport the cargo to American markets. This second route became more feasible thanks to shipping containers and double-stack rail cars—innovations that, in the words of the Journal of Commerce, “helped fuel the rise of West Coast ports” to the Panama Canal’s detriment.

Double-stack rail cars in California. Photo by Doug Wertman

The Panama Canal is still busy today. But while Panamax (or smaller) ships represent 80% of the container ship fleet, they only carry 55% of its cargo—an amount expected to drop to 40% by 2030.

The Shovels Heard Round the World

When Panamanians approved the $5.25 billion plan to expand the canal, they did so out of fear that the canal, whose toll fees alone account for around 3% of Panama’s gross domestic product, risked obsolescence.

Yet once the digging began, it was like Adam Smith’s invisible hand fired a starting pistol.

Photo by Roger W

No analyst will claim to know exactly how the expansion will impact global trade. The ecosystem has simply grown too complicated.

Panama planned the expansion when growth prospects in Asia and the Americas looked rosy, and the financial crisis already forced canal administrators to reduce their estimates of increased toll fees. The expansion will make it cheaper to ship cargo straight from Asia to the East Coast, but for products like shoes and t-shirts, the reduced cost may not be worth the extra time it takes to sail through Panama. Or railroad operators may reduce their fees to undercut the price advantage of shipping cargo through the canal.

Yet the general expectation in the industry is that the expansion will return trade to East Coast ports that had been lost to the West Coast. On the East Coast, the Panama Canal’s renewed role as a standard-setter is obvious.

Photo by Biberbaer

Ports like Jacksonville, Savannah, and Newark plan to spend north of $5.5 billion readying their ports for “New Panamax” ships, and Gulf ports in Texas and Louisiana are doing the same. The Port Authority of New York and New Jersey is spending $1 billion to raise the Bayonne Bridge so that New Panamax ships can sail underneath it. Jacksonville will deepen its harbor at a cost of $766 million.

Increasing the physical size of ports, however, is not enough to accommodate New Panamax ships. Taller ships need taller cranes to unload cargo, and bigger ships and more cargo means ports need more warehouses and more (or more productive) rail and highway links.

The canal expansion has also sent people scrambling beyond East and West Coast ports. American railroads are increasing capacity in expectation of more cargo. Shippers are building New Panamax ships, which has led the Journal of Commerce to speculate about how soon Panamaxes may be scrapped. The prospect of fewer but larger cargo ships arriving also creates opportunities for transhipment: ferrying cargo on smaller vessels to and from the New Panamax ships to smaller ports.

The Panama Canal is a mover and shaker again.

***

The administrators of the Panama Canal can’t rest on their laurels.

Since the expansion began, shipping companies have built even larger vessels that won’t fit through the new locks. Although shipping industry insiders debate how much larger container ships can grow before they hit diminishing returns, Panama is already considering another $17 billion expansion that would make it as wide as the Suez Canal. But this year, administrators already announced higher tolls to pay for the $1.5 billion cost overrun of the original expansion, which has led shipping companies to question whether alternatives like the Suez Canal and American railroads offer a better value.

The canal also faces competition in Central America. A Hong Kong-based company has signed an agreement with the Nicaraguan government to build a canal—even though most analysts dismiss its ambitions as outlandish or even as a cover for a land grab. Guatemala and Honduras plan to build a “land bridge” of railroads and highways.

For now though, Panama’s 4 million inhabitants are benefitting from the paradoxical implications of canals: that they turn the smallest places on earth into the biggest players.

![]()

Our next post investigates who is more distracted by their phones during dinner: teenagers or adults. To get notified when we post it → join our email list.