This post was written by Alex Mayyasi. Follow him on Twitter here or Google Plus. To get occasional notifications when we write blog posts, sign up for our email list.”>

On Wall Street, the term “random walk” is an obscenity. It is an epithet coined by the academic world and hurled insultingly at the professional soothsayers. Taken to its logical extreme, it means that a blindfolded monkey throwing darts at a newspaper’s financial pages could select a portfolio that would do just as well as one carefully selected by experts.

~ Burton G. Malkiel, A Random Walk Down Wall Street

In his Princeton class, economics Professor Burton Malkiel once had his students create charts of fictional stocks by flipping a coin. The stocks started at a price of $50. Each day, the stocks either gained or lost fifty cents in value depending on the coin flip.

As the class soon realized, their stocks’ “investment history” looked realistic. Malkiel even showed one to a “chartist,” an investor who picks stocks solely by analyzing stock market charts under the assumption that certain patterns repeat themselves. Malkiel describes the analyst’s reaction:

One of the charts showed a beautiful upward breakout from an inverted head and shoulders (a very bullish formation). I showed it to a chartist friend of mine who practically jumped out of his skin. “What is this company?” he exclaimed. “We’ve got to buy immediately. This pattern’s a classic. There’s no question the stock will be up 15 points next week.”

A random walk, referred to in the above quote from Malkiel’s investment book A Random Walk Down Wall Street, describes movements or changes (like the price fluctuations in Malkiel’s fictional stocks) that follow no discernible pattern. Malkiel’s experiment asked whether Wall Street analysts might be assuming an ability to detect patterns and predict stock fluctuations that occur with all the logic of a coin flip.

One commentator on the random walk idea quotes Nassim Taleb in Fooled by Randomness:

Just as one day some primitive tribesman scratched his nose, saw rain falling, and developed an elaborate method of scratching his nose to bring on the much-needed rain, we link economic prosperity to some rate cut by the Federal Reserve Board or the success of a company with the appointment of the new president “at the helm.”

The random walk hypothesis does not mean that companies (and their stock price) rise and fall randomly. The existence of persistently successful investors like Warren Buffett suggests that long-term investments based on a business’s fundamentals can pay off, and all investors can ride the slow, steady upward trend of the market.

But the random walk hypothesis would mean that Wall Street types delude themselves when day trading and trying to arbitrage short term fluctuations in a stock’s price. It would mean that daily fluctuations are too random to predict by a stock’s trading history or news announcements. All those day traders — by the random walk idea — are simply confusing the signal for the noise.

The Appeal of Man vs Monkey on Wall Street

If correct, the random walk hypothesis and its variants would mean that an incredible number of well compensated investors are charlatans, charging exorbitant management fees to invest individuals’ money no better than an average mutual fund or a monkey picking at random. And as Malkiel writes, “financial analysts in pin-striped suits do not like being compared with bare-assed apes.” But the idea has appeal for banker bashers.

In 2010, a Russian circus monkey named Lusha picked an investment portfolio that “outperformed 94% of the country’s investment funds” to great acclaim. Given 30 blocks, each representing a different company, and asked “Where would you like to invest your money this year?”, the chimp picked out 8 blocks. An editor from a Russian finance magazine commented that Lusha “bought successfully and her portfolio grew almost three times.” He suggested that “financial whizz-kids” be “sent to the circus” instead of rewarded with large bonuses.

Lusha’s investment experience is not exactly ironclad proof of Malkiel’s monkey challenge. But the question of whether monkeys could do the job of financial analysts was picked up years earlier by no less stodgy an institution than the Wall Street Journal.

The WSJ Dartboard Contest

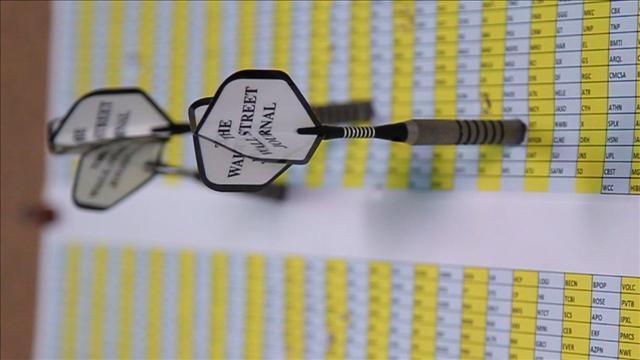

The Journal did not use actual monkeys. Insurance concerns (and probably office productivity concerns) robbed the world of that. Instead, staff at the Wall Street Journal played the role of the chimps, throwing darts at financial pages hung on the wall.

The monkey portfolio consisted of 4 stocks hit by the staffers’ darts, while 4 stock picks, each from a professional investor, made up the competing portfolio. The Journal published the portfolios of each and then compared the results — at first a month later, then 6 months later.

The Wall Street Journal Dartboard contest ran as a feature in the paper forover a decade. But 14 years, during which a number of academic papers investigated the contest results, proved insufficient to settle the competition between man and monkey’s investment prowess.

Over the course of the contest, the professionals did seem to come out ahead, as noted by the Journal in an article announcing the end of the contest in 2002:

But in the end, after 142 six-month contests, the pros came out ahead, racking up an average 10.2% investment gain. The darts managed just a 3.5% six-month gain, on average, over the same period, while the Dow industrials posted an average rise of 5.6%. The pros also outperformed Wall Street Journal readers, who were invited to join the fray in 1999.

Despite those statistics, not everyone agreed that the pros beat the darts, and the same article declined to declare a winner. One reason why is that professional investors barely beat the monkeys in the head to head results. As Investor Home reports on the results of the first 100 dartboard contests:

The pros won 61 of the 100 contests versus the darts. That’s better than the 50%… [but] losing 39% of the time to a bunch of darts certainly could be viewed as somewhat of an embarrassment for the pros. Additionally, the performance of the pros versus the Dow Jones Industrial Average was less impressive. The pros barely edged the DJIA by a margin of 51 to 49 contests. In other words, simply investing passively in the Dow, an investor would have beaten the picks of the pros in roughly half the contests (that is, without even considering transactions costs or taxes for taxable investors).

Critics also pointed to problems with the contest that they charge biased the results in favor of the pros.

Malkiel — who threw the first dart at the start of the contest — criticized the choice of a 4 stock portfolio. The small number of stocks represented the non-rigorous nature of the competition — the Journal called the dartboard contest “light-hearted.” But Malkiel and fellow minded investors advocate for a passive investment strategy of mutual funds that rise modestly but consistently with the growth of the stock market. Picking only 4 stocks, therefore, invalidates the blindfolded monkeys’ advantage.

From the start, Malkiel also complained that printing the investors’ stock picks would skew the results. Since the Journal published the portfolios at the start of the contest, the paper’s 1.5 million plus subscribers saw their recommended picks, bought them, and drove up the price. A paper in the Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis confirmed this. The authors found that the professional investors’ stock picks experienced unusually high returns and trading volume in the days following publication, although the WSJ extended the length of the contest from one month to 6 in order to mitigate this concern.

But by far the biggest challenge to the professional investors’ victory over the darts was that the results did not account for risk, nor for dividends. A number of academic papers (summarized here) found that the investors’ portfolios were much more risky and paid out less in dividends than the stocks picked by dart. As a result, the competition was less a fair fight and more a comparison of apples to oranges. Or, in this case, US treasury bonds to technology stocks.

Investing is a trade off between risk and reward; the choice of seeking higher returns through riskier stocks (like technology companies) is an investment decision — not the mark of a savvy investor. A bond investor chooses the safety of the U.S. government, which is still considered the safest investment around, and its regular payouts. The technology investor, in contrast, risks big losses during a new tech bubble or to the breakout of competitors for the upside of larger gains in share price.

The dartboard contest took into account neither risk nor dividends. Since the professionals chose stocks that paid out fewer dividends, the monkey portfolio didn’t get credit for its dividend gains. And since the pros chose riskier stocks, the dart picks didn’t get credit for being a safer investment. In other words, the professionals’ higher returns were not necessarily the result of savvier picks, but the expected result of choosing a riskier investment strategy. Apparently entrusting your money to blindfolded monkeys is a more conservative investment strategy than professional Wall Street money managers.

Beating the Darts

Like many great debates, Malkiel’s challenge to professional investors remains unresolved by experiments like the Wall Street Journal’s dartboard contest. (Other academic papers simulated the thought experiment with random number generators playing the role of blindfolded monkeys.)

From this author’s perspective though, the test still seems like a moral victory for the blindfolded monkeys. As one article on the contest notes, “We are talking about a contest that originated from what was initially considered by many people to be an absurd theory – that a primate could pick stocks as well as intelligent, well educated, and highly compensated investment professionals.” Even if the monkeys did lose on the scoreboard, the fact that so many investigations side with the monkeys, and the fact that they came close, seems like a moral victory.

But one clear lesson did emerge from the dartboard contest. After retiring the competition in 2002, the Wall Street Journal continued letting readers compete with the darts. And in June 2013, one reader crushed the darts so thoroughly — he turned his $100,000 into $5,541,631.87 to the darts’ $104,881.51 — that his superiority over random chance could not be disputed.

How did the well-named reader, Arthur Golden, do it? He cheated. Or at least skewed the rules. As the WSJ wrote:

The real secret to his success was his clever exploitation of a loophole in the game that made it distinct from a real-world trading scenario: Because the virtual stocks sold for their last traded real-world price, Mr. Golden was able to buy and sell large blocks of lightly traded stocks without affecting the price of those stocks.

So he made six-figure profits off minute changes in stock price.

In a kind of inversion of the high frequency trading performed by Wall Street algorithms, Golden spent 5 hours a day arbitraging this loophole. His huge victory reminds us of the clearest example of how finance professionals can perform better than random chance: cheating, loopholes, and investing in ways impossible for the rest of the market to match.

This post was written by Alex Mayyasi. Follow him on Twitter here or Google Plus. .