Skirting the desk in his San Francisco office, Dr. Friedenthal retrieves an open binder full of pictures of women’s legs, breasts, and butts. No faces are visible, and every woman is wearing simple, white underwear. It is unclear whether each woman owns a similar pair, or whether it is provided for the photograph.

The binder belongs to Dr. Roger Friedenthal, an accomplished plastic surgeon who teaches at the UCSF School of Medicine and performs procedures like facelifts and liposuction in private practice.

Handing over the binder, he points to a pair of before and after pictures. “If you go from this to this,” he says, “you will be happy.” The pictures are from a breast reduction surgery. “It’s kind of cool. She looks cute and it’s less strain on the back.”

A seeming paradox has brought us to Dr. Friedenthal’s office: People spend billions on makeup, teeth whitening strips, and hair dye to improve their physical appearance without a second thought, yet plastic surgery is widely derided. Even in cities and social circles where it is common, few talk openly about their surgeries.

Plastic surgery does require facing the dangers of surgery for non-medical purposes. And many people (falsely) believe that plastic surgery inevitably looks fake. But our hunch is that people scorn plastic surgery primarily because – by siphoning away fat or removing signs of aging – it seems to break the rules.

Physical appearance has a huge impact on our lives. It shapes our dating prospects, chances of promotion, and much more. Everyone knows that this is true and unfair. Ye we have accepted it and seek to control what aspects of appearance we can by working out, using makeup, or selecting flattering clothes. These are the rules.

Plastic surgery threatens to break those rules, to make something as central to our identity as appearance completely malleable. And people hate nothing so much as learning that someone is breaking the rules they have accepted as given – no matter how unfair the game.

We spoke to three accomplished surgeons and came away with an impression of a misunderstood industry. Good surgery can improve one’s appearance without looking unnatural. But rather than offering a radical change of appearance, cosmetic procedures operate like braces or dye for gray hair: They slow the signs of aging or bring an inelegant feature into proportion with the rest of the body. But looking at the wider industry, we also found reason to doubt that these surgeons’ restrained, natural vision of cosmetic surgery will remain the norm.

From Reconstructive to Cosmetic

The first rhinoplasty, or nose job, was performed in ancient India, yet the field of cosmetic surgery is young enough that today’s experienced plastic surgeons have seen much of the development of the field.

Plastic surgery, whose etymology is the Greek plastikos, meaning “able to be molded,” denotes a field of reconstructive surgery that has for centuries dealt with the replacement or repair of body parts. Its modern practice grew out of the treatment of blasts and burns after World War I and World War II. The volume of cases that did not fit a traditional division in surgery prompted plastic surgery to become its own field. The advancements driven by the treatment of veterans enabled the development of cosmetic surgery – plastic surgery done purely to improve one’s appearance.

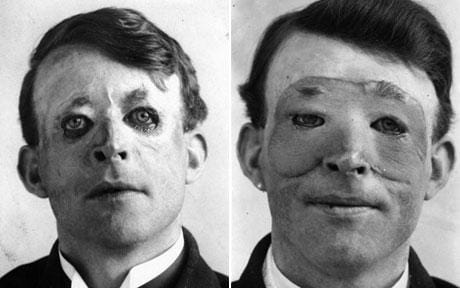

Before and after photos from a plastic surgery for reconstructive purposes in 1917

Dr. Friedenthal can describe cosmetic surgery’s development from experience. When he trained as a doctor, physicians performed skin grafts by shaving off a bit of someone’s skin – like a child scrapes his skin falling off a bike – and performing a skin transplant. Surgeons did this for patients who lost a big piece of tissue in an accident so as to move skin to the injured area.

Then, Dr. Friedenthal told us, “a big thing happened.” Doctors discovered that since skin receives its blood supply from the underlying muscle, and one artery or vein in turn supplies blood to the muscle, you could lift up the skin and muscle with its hanging vein or artery and attach it the the blood supply elsewhere.

As this developed, a San Francisco doctor named Harry Buncke was researching transplants. Dr. Friedenthal, who worked with Dr. Buncke, described his key innovation as the ability to sew tiny blood vessels together. He demonstrated its potential by successfully reattaching the severed ear of a rabbit.

As a result of these two innovations, in Dr. Friedenthal’s words, “all hell broke loose.” Surgeons could pick up skin and muscle from one part of the body to make a new breast for a women who had a mastectomy. Among other acclaimed surgeries, Dr. Buncke removed two toes from a man who had lost four fingers during an earthquake. He crafted two new fingers from the toes, allowing the man, a plastic surgery intern, enough dexterity to continue his career. In other words, the human body began to look actually plastic and malleable.

“This is a big field,” Dr. Friedenthal noted, as he described the many awe inspiring applications of plastic surgery for victims of accidents and genital defects, at one point miming splitting his head in two to summarize facial cleft surgeries that correct congenital disorders. Plastic surgeons performed 5.6 million reconstructive surgeries (such as those for burn care or facial clefts) in 2012. Surgeons performed over 10 million minimally invasive cosmetic procedures, but only 1.6 million surgeries for purely cosmetic purposes. “Although most people focus on it,” Dr. Friedenthal told us, “cosmetic surgery is only a tiny part.”

Beauty Out of Proportion

“I was one of first in the US to [perform] liposuction. This was way back. I saw this French fellow talking about ‘ze liposuction’ and reshaping bodies at a conference and I was fascinated. Soon I was in Paris with five other people taking his course. For our graduation dinner he took us to the Moulin Rouge. It was very strange. I don’t know how many people spend hours looking at what the French think beautiful buttocks look like. They’re not just pillows. They have shapes, differences.”

~ Dr. Roger Friedenthal

Artists, models, and scientists could all partake in endless debates about what it means to be physically beautiful, but plastic surgeons need to have a ready answer to do their work.

Dr. John Shamoun, who has a prominent cosmetic surgery practice in Los Angeles, stressed that plastic surgeons must be artists as well as scientists. He classified plastic surgeons as either Da Vincis or Michelangelos. Each artist created inspirational works of art in different ways. Da Vinci used an engineering approach highlighting “golden proportions.” Surgeons in this school “may draw marks and measure someone’s face for 20 minutes before a surgery starts.” Others just create intuitively like Michelangelo – following their own mental plan of what looks good.

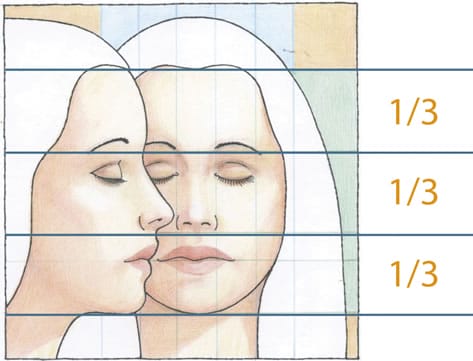

To the extent that plastic surgeons receive artistic training, it is a Da Vinci study of proportions. Surgeons learn, for example, that a balanced face can be split into thirds of equal length. Unlike a block of granite, however, human tissues are dynamic. Not all features are reworkable and the price of failure is incomparable to the destruction of a canvas.

Dr. Shamoun insists that the two schools are different yet equal in ability. But his words seem to reveal a preference. All the surgeons we spoke to recognized the importance of proportion. Despite the idea of beauty being “in the eye of the beholder,” it has an objective basis. Referencing research Priceonomics readers will recognize from our prior article on attractiveness, Dr. James Romano, who runs a practice in San Francisco, described studies that looked at how pictures of beautiful people, with symmetry in their features, drew infants’ gaze, while Dr. Friedenthal noted studies that looked at how people rate proportional features as more beautiful.

They also all found proportion necessary but insufficient. “I’m not a numbers or measurement person,” Dr. Shamoun told us, putting himself in the Michelangelo camp. “I’ve seen numerous patients with nose measurements outside of the norm whose noses were absolutely perfect on their face. If I altered it, I would create a ‘blender’ – someone who would just blend in with everyone else. You don’t want to take that character away. It’s how all the parts fit together that make people interesting.”

Dr. Friedenthal agreed. In his San Francisco office, he handed us a “reversing mirror.” The mirror shows people the reverse of the reflection they normally see in a mirror. Since this does not match their mental image of themselves, it emphasizes their asymmetries. As we puzzled over our strange reflections, he exclaimed, “Most people hate how they look in that mirror!” Yet Dr. Friedenthal quoted Sir Francis Bacon (“There is no excellent beauty that hath not some strangeness in the proportion”) as he explained how beauty does mean not averageness or perfect proportionality. Instead, it exists around the mean.

All three agreed that an individual surgeon needs to respect proportion, but also develop their own style and sense of what looks good for each feature. Even if that means staring at beautiful people onstage at Moulin Rouge.

The Limits of Surgery

To understand the limitations of surgery, we asked Dr. Shamoun whether it could help an unattractive person become beautiful. Or, in more blunt terms, whether he could turn a “one” into a “ten.” He seemed used to the question:

“Absolutely not. Not even close. You must work with what you’re given. But you can help someone who has an imbalance in their features and bring balance to their face. So if you walk into a crowd and notice someone because they’re ugly – now you wouldn’t notice them for that reason after restorative surgery.”

He made clear that interventions have to be individualized for one’s features – a point Dr. Friedenthal underlines as well:

“There are many variables. Not everybody is the same and they don’t age the same. Dealing with large noses with large mouths is different than large noses with small mouths.”

The skill set for reconstructive surgery (to repair effects of an accident or congenital defect) and cosmetic surgery is one and the same. While cosmetic surgery is different in that it is chosen in a way that a burn victim’s skin transplant is not, the rhetoric of the cosmetic surgeons we spoke with reflected a very corrective interpretation of the practice. While they believed in the transformative power of surgeries, they described themselves as “correcting” imperfections or imbalances.

Patients occasionally ask surgeons “What should I get?” But it’s rare. “Patients are realistic,” Dr. Romano told us. “They come if they have something that is really out of proportion or that they don’t want. It’s not someone that has something beautiful and wants it better.” Dr. Shamoun sees cosmetic surgery as primarily rejuvenative – where people like their features but not what time has done to them – or corrective – where something is not fitting the norm and you try to make it more harmonious with their features. People spending money without something to fix exasperate him: “They’re spending money just to make lateral moves! They would be better treated in a therapist’s office.”

It’s a distinctive problem of plastic surgery that people notice only botched surgeries and never successful ones. Surgeons attribute celebrities with “fish lips” or other unnatural features to poor surgeons that failed to correctly understand shape or individualize the intervention. The repetition of the word “natural” by plastic surgeons is not propaganda. “Good plastic surgery should be unnoticeable,” we hear over and over. “You unknowingly pass people who had plastic surgery every day.” Celebrities with bad plastic surgery perpetuate the image of the practice as chasing the same idealized, bombshell look in every operation.

Would Hippocrates Approve?

In 2004, Fox broadcast a series called The Swan. It chronicled the experiences of a number of women as a team of beauticians, a plastic surgeon chief among them, transformed them from ugly ducklings to beautiful swans – at least by the logic of the show’s title. A therapist and coach also helped them with their personal and professional life.

Critics decried the show as equating a surgical makeover with self-esteem, representative of American culture’s propensity to measure all value before the altar of youth and attractiveness. People generally seem to look down on the practice as superficial and vain.

Dr. Shamoun disagrees with this criticism of the field: “Let’s face it. You get better jobs and spouses the better looking you are. Sorry, but that’s the way it is. I didn’t say it was right.” He disapproves of people getting unnecessary surgery, but insists that “if your degree of concern about something is proportional to your problem, then you’re a realistic patient.”

This is the response of most surgeons. “Undergoing surgery for appearance reasons is not trivial,” Dr. Friedenthal said calmly, noting that as with all surgeries, cosmetic procedures can have complications and necessitate recovery periods. “But appearance is not trivial. The reason we don’t look like neanderthals is a function of selection. It’s like trying to argue with the weather. You don’t need [surgery]. Barbra Streisand did wonderfully and she had a large nose. But most of us can use what help we can get.”

The evidence backs up the surgeons’ statements. As Priceonomics wrote in a previous article:

Humans like attractive people. Those blessed with the leading man looks of Brad Pitt or the curves of Beyonce can expect to make, on average, 10% to 15% more money over the course of their life than their more homely friends. Without being consciously aware that they are doing it, people consistently assume that good-looking people are friendly, successful, and trustworthy. They also assume that unattractive people are unfriendly, unsuccessful, and dishonest. It pays to be good looking.

Doctors can make good money in cosmetic surgery. But a variety of non-financial reasons also draw surgeons to the practice. It’s a chance to use surgery skills in a particularly creative way and to work with healthy and happy patients – a rarity in surgery.

We were also impressed by the care surgeons took to remain doctors rather than salesmen. “I come from a position of responsibility, so I could make people insecure about something they weren’t insecure about,” Dr. Friedenthal volunteered at one point in our conversation. “I could sell them on additional procedures. I am really careful not to do that.” Dr. Romano added later, “I’ve had a huge positive impact on someone by telling them not to get plastic surgery.”

And the surgeries can have a lasting positive impact. Scholarly literature on cosmetic surgery suggests that patients with what Dr. Romano would call “realistic expectations” generally report improved quality of life that persists over time.

Dr. Friedenthal parrots one of his former patient: “I’ve got a new boyfriend who’s 10 years younger.” Another patient who was morbidly obese, slimmed down, and came to Dr. Friedenthal to be “trimmed up” came in smiling and said that he’s dating a model. “It’s a thrill when you see it turn out really good,” the doctor tells me. “A lot of caterpillars become butterflies in here.”

Patients cite a variety of reasons for seeking surgery, such as improving their dating prospects or avoiding workplace discrimination against the elderly. But rather than being the superficial creatures many critics of cosmetic surgery assume, they seek surgery because of the limitations placed on them due to their looks. “I don’t see vanity here,” Dr. Friedenthal told us. “I see the opposite.”

If critics of cosmetic surgery criticize the practice based on the world as they think it should be, surgeons claim to be helping victims of the world being as it is. No one shames people who become beautiful thanks to an orthodontist fixing their teeth with braces, or a breast cancer survivor who receives implanted breasts. Yet the majority of these doctors’ cosmetic surgery patients do something similar.

Plastic Surgery Gangnam Style

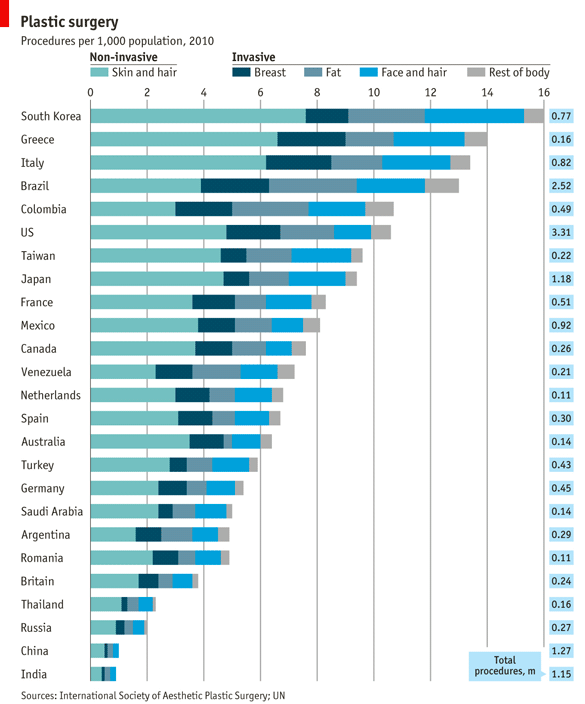

As the young field of cosmetic surgery matures, South Korea may offer a glimpse into its future. While the United States has the largest cosmetic industry, it is most prevalent in South Korea, where 1 in 5 individuals receives some form of cosmetic surgery.

Graphic from The Economist

Looking through the crystal ball of South Korea leads us to question whether the natural, corrective interpretation of the practice espoused by the surgeons with whom we spoke represents the industry’s future. Accounts from South Korea describe comsetic surgery as a teenage rite-of-passage for girls similar to American teens getting their ears pierced. With seemingly every girl from an upper class background receiving surgery, it seems impossible that everyone is seeking to correct an “imbalance.”

More Korean men are also seeking surgery, something happening on a lesser scale in the United States. But it remains primarily a practice for women. In the US, ninety one percent of patients were female in 2012. A longtime complaint is that women feel forced into surgery to meet men’s physical expectations. Looking to Korea, it’s unclear this gender imbalance will ever fade, or that it would be a positive development if it did.

Dr. Friedenthal related the story of a lesbian patient of his. While receiving reconstructive surgery after a mastectomy, she told him angrily “I’m not doing this for men!” Yet when 9 women get surgery for every 1 man that does, can we really discount that social forces, rather than unchangeable human nature, influence patients’ choices?

Korean surgeons also go to great lengths to create a certain look that is more caucasian or reflective of Korea’s pop music stars. Double eyelid surgery, which make the eye more caucasian looking, are considered an initial, minimum procedure. And in pursuit of a narrow face, Korean women increasingly receive radical surgeries that break and manipulate the jawline to create a v-shaped face.

Not only does this shatter the idea of natural corrections, it suggests a future of unsafe practices in pursuit of a particular look. Jawline surgery can cause serious health problems from permanent numbness up to death. In a harbinger in America, Dr. Shamoun described a flood of “injectables” that are mostly hype and whose risks aren’t yet truly known. Yet they are offered to patients.

He has also receives requests for a specific look. The “twiggy look” was “in” for awhile, he told us, followed by a more “full body look.” He believes that aspiring to the current “starlett modality” is a mistake, but if Korea is a valid indicator of future trends, the natural view may bow to customer demand. As cosmetic surgery gets more common, it’s not hard to imagine people coming in with pictures of the celebrity they want to look like, or changing their look to conform with the “in” look of the season.

Is this the future of cosmetic surgery in America?

A Growing Practice?

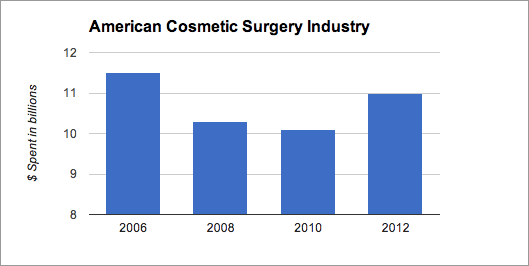

Due to the recession, the American cosmetic surgery industry is growing in some ways and stalled in others, which makes it hard to guess whether the American market is headed for the future represented by South Korea.

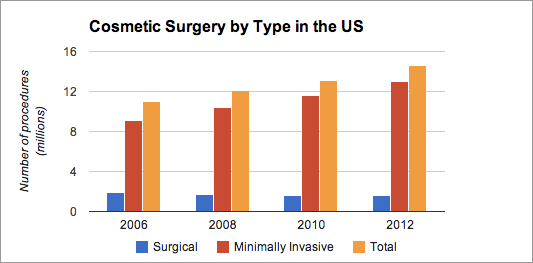

Americans spent $11 billion on cosmetic surgery in 2012, according to the American Society of Plastic Surgeons, and an estimated 1 in 20 Americans has had some form of cosmetic surgery. The total size of the industry has remained relatively stable over the past 5 years, although the number of procedures performed has increased over time – up 5% last year to 14.6 million procedures. That is due to a trend toward less expensive, “minimally invasive procedures” such as botox injections and chemical peels. Surgeons performed each of the most popular non-invasive options one to six million times in 2012 but performed the most popular surgery – breast augmentation – under 300,000 times.

Data source: The American Society of Plastic Surgeons

This could represent a rejection of Korean-style transformations. Surgeries are generally required for radical changes while minimally invasive procedures are more often for rejuvenation purposes. Then again, it could be that the recession led people to choose procedures they can afford, and that boom times will lead to a renewed surge in more dramatic surgeries.

Cosmetic surgery is becoming more accepted. The derision Americans hold toward the practice has eroded to the point that surgeons insist that plastic surgery is at least tolerated, if not accepted. “Mention of plastic surgery used to be hushed the way people talk about cancer,” Dr. Friedenthal told us. “People still don’t brag, but it is accepted and not frowned on a lot, at least around here.”

He referenced several television programs like The Swan as helping plastic surgery gain acceptance. While the show’s depiction of surgery turning around the lives of the contestants did not match the “reasonable expectations” of surgery he espouses, Dr. Friedenthal volunteered that it was a “nice opportunity for people to realize that surgery is a good option that you have.”

Dr. Romano told us “that fewer and fewer people are judgmental” across the many cities and areas where he has performed surgeries. That said, people still generally hope for their surgery to go as unnoticed as a significant physical change possibly can. Dr. Shamoun practices in Los Angeles, a city known for a forever-young, beauty conscious attitude. A few people “want everyone in their book club to know,” he told us. “But I’ve had patients who pretend not to recognize me at a restaurant because they don’t want anyone to know.”

Rumors of young celebrities going under the knife draw headlines, but the middle-aged dominate the market. Patients 40-54 years old account for 48% of procedures and those above 55 another 26%. Teens and twentysomethings represent under 10% of procedures. While the number of procedures are increasing across all age ranges, they are increasing most quickly among older individuals. The growth of plastic surgery is fueled by the 76 million Baby Boomers. At ages 49 to 68, they already spend over $80 billion on anti-aging products.

The industry will continue to grow as Americans live longer and seek out youthful looks to match their longevity. But these trends suggests that the American cosmetic surgery market is still mostly about making older individuals look like their younger selves, not crafting a new look for young people.

The Future of Cosmetic Surgery

After discussions with three of the West Coast’s top plastic surgeons, we came away with an impression of cosmetic surgery at odds with its stereotypes. The surgeons presented a vision of the practice as a corrective or rejuvenative one no different from braces or dye for gray hair. The field recognizes the reality that no one lives up to their rhetoric of not judging a book by its cover. But many surgeons do so to help the victims of lookism escape the limitations of unattractive features more than to help vain individuals look better and better.

However, we also find reason to doubt this reassuring vision of cosmetic surgery. The gender imbalance among patients suggests that social forces drive women to surgery. And as Korea demonstrates, the future of cosmetic surgery may not be a corrective, natural one pursued only by people bothered by a particular inharmonious feature. It could be a universal prerequisite to pursue – often in dangerous ways – a particular look or fashion unrelated to their natural looks. In short, it could be cheating.

Dr. Friedenthal told us that trying to argue against the importance of good looks in life is like arguing with the weather. But it seems to us that some of the storms are man-made, growing more turbulent when our culture stresses more and more our natural inclination to value physical appearance. If the forces leading patients into Dr. Friedenthal’s office are the weather, then the cosmetic surgery industry will be the barometer, measuring over time how well we live up to the maxim don’t judge a book by its cover.

This post was written by Alex Mayyasi. Follow him on Twitter here or Google Plus. To get occasional notifications when we write blog posts, sign up for our email list.