Over the course of United States history, forty-four men have served the nation as President. Immortalized on granite mountains, textbook covers, and placemats, their faces are forever etched in American lore; their stories are remembered and celebrated.

But unwritten in textbooks is the history of the United States’ one-time imperial ruler: on a September evening 150 years ago, a man named Joshua Abraham Norton proclaimed himself Emperor of the United States. For nearly 30 years, the delusional ex-merchant ruled his home-city of San Francisco (and the nation) with benevolence and became one of the most revered figures of the century. Upon his passing, 30,000 attended his funeral, and he was commemorated by the likes of Mark Twain, Robert Louis Stevenson, and Neil Gaiman.

A Ruler is Born

Joshua Abraham Norton was born in England somewhere between 1814 and 1819. When he was only a few years old, his family migrated to South Africa, where his father operated a ship chandlery and sold supplies and equipment to seamen. In his early twenties, Norton attempted to start a business, but failed miserably and soon joined his father as a helping hand.

By 29, Norton’s entire family — a mother, a father, and two brothers — had passed away. After inheriting his father’s $40,000 will ($1.1 million in 2014 dollars) in 1849, he took to California, where the Gold Rush had recently attracted droves of hopefuls looking to strike it rich. But instead of mining, Norton established a merchant business and rented out ship space to importers. As his business grew, he purchased an arsenal of investments — a cigar factory, a rice mill, and an office building; within four years’ time, the shrewd businessman had amassed a $250,000 fortune ($6.9 million today). Unfortunately, Norton’s success ceded to greed; eventually, it got the best of him.

At the time, China was the main supplier of rice in San Francisco. When a famine cut off shipments in 1852, the price of rice skyrocketed from 4 to 36 cents per pound (an 800% increase). Another merchant had a ship full of 200,000 pounds of rice and offered it to Norton for 12.5 cents per pound. “At $25,000 for the shipload,” he told Norton, “you could sell it for 36 cents per pound and gross $72,000 (a 300% profit)!” With a $2,000 down payment, Norton signed a contract and agreed to pay the full fee within 30 days.

The next day, a fleet of ships arrived from Peru loaded with rice; within the week, there was enough rice to feed San Francisco a thousand times over. Norton had been swindled. He sued the merchant, and a costly two-year legal battle ensued; eventually, he lost and was ordered to pay the remaining $23,000. This would prove to be the catalyst for his downfall.

By 1855, the Gold Rush had ended: prices deflated on everything, the real estate market collapsed, and banks failed. Norton joined legions of businessmen in filing for bankruptcy, and was forced to sell off his assets at a huge loss. For some time, he lived in poverty, working odd jobs and brokering coffee, before altogether disappearing from the San Francisco social scene.

The Emperor Strikes Back

It was an intense period in America: the Panic of 1857 had left many in financial ruins, the Dred Scott case, which ruled that African Americans couldn’t be U.S. citizens, was an indirect catalyst for the Civil War (1861-1865), and there was a pervading sense that California would cede from the states and form it’s own sovereign nation. When Joshua Norton resurfaced in San Francisco in the late 1850s, he was a new man, with a new sense of purpose.

Norton befriended the editor of the San Francisco Bulletin and, on September 17, 1859, published a decree in which he proclaimed himself Emperor of the United States (unbeknownst to James Buchanan, U.S. President at the time):

“At the pre-emptory request of a large majority of the citizens of these United States, I Joshua Norton, formerly of Algoa Bay, Cape of Good Hope, and now for the last nine years and ten months past of San Francisco, California, declare and proclaim myself the Emperor of These United States, and in virtue of the authority thereby in me vested do hereby order and direct the representatives of the different States of the Union to assemble in Musical Hall of this city, on the 1st day of February next, then and there to make such alterations in the existing laws of the Union as may ameliorate the evils under which the country is laboring, and thereby cause confidence to exist, both at home and abroad, in our stability and integrity.”

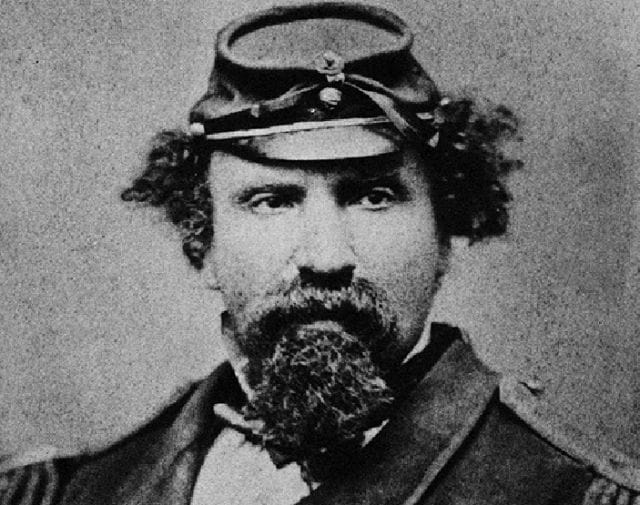

To little fanfare, Emperor Norton assumed his post and went about business. Clad in a baggy, ill-fitting military uniform and a beaver hat ornamented with an array of peacock feathers, Norton took to the streets of the city to make his presence known. According to one account, he “looked and acted every inch a king,” carrying a ceremonial sword at his side and bearing an umbrella as his scepter. Stocky and bearded, he walked tall, and with an air of elegance; his royal court — two mongrel dogs — trotted by his side.

His first order of rule was ensuring that the city was operating hitch-free: he took care that sidewalks were unobstructed, police were on duty, and buildings were being constructed up to code. With an encyclopedic knowledge of city ordinances (some of which were no more than a figment of his imagination), he served as any noble, righteous-minded leader would, and set about trying to change the city for the better.

The citizens of San Francisco not only accepted Norton’s rule, but entertained the royal treatment he commanded: he was given free transportation, special seating at plays and musical performances, and free restaurant meals. Owners vied for his royal approval, pinning up brass plates outside of their establishments begging for the Emperor’s presence. The city of San Francisco even allocated an annual budget for the Emperor’s trappings (for this, Norton granted each supervisor with a “patent of nobility in perpetuity”).

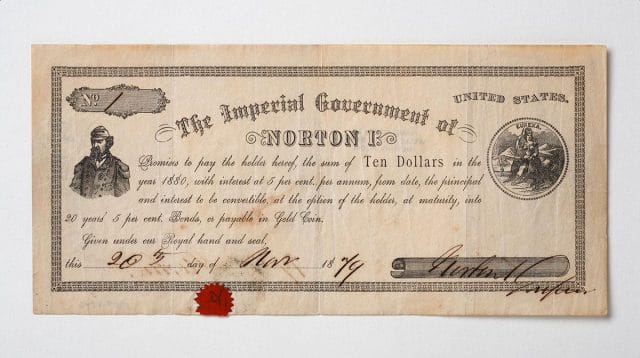

To pay for his debts, Norton collected taxes and issued bonds — and people complied with his demands. He was a wise dictator, and took great care in not making outrageous claims; his needs were frugal, and his financial demands were sparse. When Norton decreed his own currency, local printers jumped on board and printed it free-of-charge:

San Franciscans took great pride in their new Emperor, and humored his delusions. Historian Patricia E. Carr recounts his early treatment:

“Whether it was a salute or a bow as they passed him on the street, they universally gave their Emperor the tribute he expected. They even listed him in the city directory as ‘Norton, Joshua (Emperor), dwl. Metropolitan Hotel.’ They gave him a place of honor at plays, concerts, public lectures, and other civic affairs. The police department – Norton’s ‘Imperial Constabulary’ – reserved a special chair for him at the precinct station and even prevailed upon him to march at the head of their annual parade.”

In the 1870 Census, Norton is listed as residing at 624 Commercial Street — an apartment paid for by the city; his occupation is listed as “Emperor,” and there is a disclaimer that the man is “insane.”

When a policeman arrested Norton and had him committed to a mental institution, the community created an uproar, and newspapers posted editorials damning the justice department. So much pressure mounted that the chief of police not only released Norton, but issued an apology. “He had shed no blood; robbed no one; and despoiled no country,” he wrote. Norton subsequently granted the chief an “imperial pardon” for his mistake, and he was saluted by officers whenever he went out in public.

Anti-‘Frisco’ Campaign, and Politics

During the course of his “rule,” Norton I made a series of proclamations and dabbled in the heavy political issues plaguing his city and nation. Though he’d lost touch with reality, his intentions were wholly benevolent. In 1872, he set out to furiously punish anyone who besmirched his city’s honor, outlawing the use of abbreviations; he made his intentions clear in The Herald:

“Whoever after due and proper warning shall be heard to utter the abdominal word ‘Frisco,’ which has no linguistic or other warrant, shall be deemed guilty of a High Misdemeanor.”

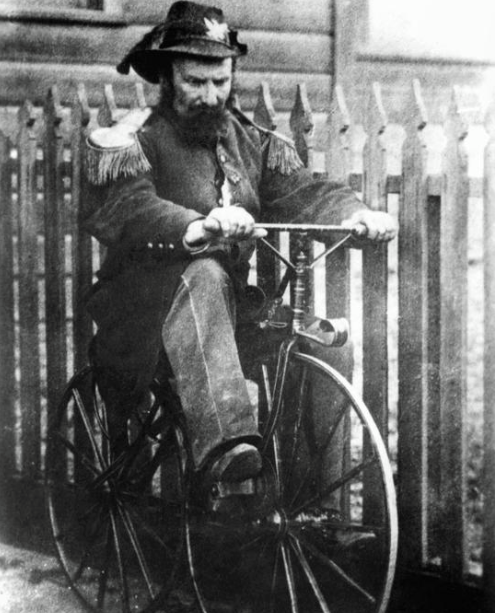

Anyone overheard saying the term would be charged $25 ($430 today) — a hefty sum. The Emperor rode his fixed-gear bicycle around town, enforcing his new “law:”

Later that year, he ordered a bridge to be built across the San Francisco Bay; while his demand was dismissed, his wisdom was later memorialized on a sign near the Bay Bridge (constructed 60 years later): “Pause traveler, and be grateful to Norton I… whose prophetic wisdom conceived and decreed the bridging of San Francisco Bay…”

The Emperor stood up for the city’s minorities and the underserved. During an anti-Chinese rally in the city, he mounted the stage, silenced the rowdy crowd, and recited a prayer; within minutes, the aggressors had calmed and dispersed. In 1878, Norton signed a petition to the California Constitutional Convention calling for women’s voting rights.

***

But Norton’s decrees expanded beyond San Francisco. In July 1860, for example, he foresaw the imminent power struggle between the North and South, and called for the dissolution of the Union; despite his eagerness to arbitrate the Civil War, nobody took him up on the offer. He pitched the idea of a League of Nations long before one was created in 1919. Fiercely non-partisan, Emperor Norton once even tried to “abolish” political parties; on August 4, 1869, he made his intentions clear in the San Francisco Herald:

“Being desirous of allaying the dissension’s of party strife now existing within our realm, [I] do hereby dissolve and abolish the Democratic and Republican parties, and also do hereby degree the disfranchisement and imprisonment, for not more than ten, nor less than five years, to all persons leading to any violation of this our imperial decree.”

The Emperor also proclaimed himself the “Protector of Mexico,” and set about ensuring the rights of recently-ousted Mexicans (though he later claimed it was “impossible to protect such an unsettled nation,” and dropped this part of his title).

Death, Legacy

On January 8th, 1880, while making his rounds, Emperor Joshua Norton I suddenly collapsed, and died of apoplexy (internal bleeding of the organs). He’d amassed such a massive following that the procession at his funeral was 2 miles long; over 30,000 attended the most elaborate ceremony the city had ever seen. “San Francisco without Emperor Norton,” one newspaper wrote, “will be like a throne without a king.”

The entire city mourned: flags were hung at half mast, business closed their doors, and wealthy patrons paid for Norton’s burial, which featured “all the ceremony that a real emperor would have received.”

Mark Twain, who wrote about the man’s life, claimed that more ink had been used to cover Norton’s obituary than any death since Abraham Lincoln’s. Twain also surmised that, though the Emperor “filled an emptiness in his life with the delusion of royalty,” he had served his people well. “O dear,” wrote Twain in a column for The Daily Call, “it was always a painful thing for me to see the Emperor begging, for although nobody else believed he was an emperor, he believed it.”

Fifty-four years later, when Norton’s remains had to be relocated to nearby Colma, the city still hadn’t forgotten his legacy: 60,000 people attended the ceremony this time, and he was donned a new, luxuriously-engraved tombstone. “Norton I,” it read, “Emperor of the United States, Protector of Mexico.”

This post was written by Zachary Crockett. Follow him on Twitter here, or Google Plus here.