One thing you can do with 11,014 Lego bricks; Source: Lenny Spiro

Sixty-five years ago, deep in the basement of a Billund, Denmark carpentry workshop, Ole Kirk Christiansen conceived Lego; 560 billion pieces later, the company has defined childhood for millions of kids across the globe.

But for some, the fun doesn’t stop at puberty. Adult fans of Lego — or AFOL (pronounced “awful”) — is a small but passionate confederacy of builders who refuse to believe Lego is just for kids. One AFOL we spoke with says most in the community are “educated and/or intelligent, and have some sort of technical background.” Many are engineers, computer programmers, and hackers who have no reservation about shelling out $2,000 on EBay for an “Ultimate Collector’s” Millennium Falcon, or a rare limited-edition set. As Jamie Berard, Lego’s senior product designer, says, “Dad’s gotta have his toy room too!”

For the select few in the AFOL community, playing with Lego bricks has become more than a mere hobby: the best of the best have made a career out of it. But how much can you expect to earn as a Lego maestro, and what exactly does the job entail? We’ve explored three jobs — model master builders, Lego Certified Professionals, and industry “renegades” — to answer these questions.

Lego Master Model Builders

Master builder Dan Steininger at work; Source: c_chan808

The road to becoming a master model builder for Lego is excruciating and arduous — and the monetary payoff is less than exciting. To give you an idea of how selective this group is, there are only 40 Lego master builders in the world, 7 of whom are Americans.

These builders are hand-picked by Lego, and are employed at the company’s Discovery centers, and its seven LEGOLAND theme park locations (Billund, Denmark; Windsor, England; Günzburg, Germany; Nusajaya, Malaysia; Florida, California). But in most cases, they have to start from the bottom and work their way up: only the most skilled Lego artisans achieve the honor of master builder.

Typically, a new hire starts as an apprentice builder — essentially a “glue minion,” according to a young “peon” who works at LEGOLAND Florida. They spend long hours adhering thousands of individual pieces together and work on maintaining the parks’ various sculptures and exhibits. From there, a promising apprentice builder is promoted to a senior builder, where the pay may bump from $10 to $12 an hour, and additional duties are assumed: constructing models, overseeing daily procedures, and shadowing the master builders.

If you’re lucky enough to be selected as a master model builder, Here’s the job description directly from Lego’s website:

“This exciting role will have you designing, building, removing, installing, and repairing all models at the attraction. As the resident LEGO® building expert, you will help teach others by running workshops, speaking with media and participate in events. We are looking for someone with flair who has the ability to create a wide range of models. Must follow design briefs to build LEGO® models for displays and marketing promotions.”

However cool building Lego sculptures all day may seem, these duties come with a few caveats. For one, the pay — $37,500 a year — isn’t stellar for a highly selective post that requires a tremendous amount of practice, energy, and time to secure. For those who wish to have true creative freedom, the master model builder position also often proves to be constricting: the majority of projects fall within premeditated or corporate-affiliated themes (Superman, Spiderman, Star Wars, etc).

To boot, all Lego-sanctioned creations must be kid-friendly (after all, that’s the company’s main constituency); custom builders wishing to create more controversial or experimental works (ie. zombie villages) simply aren’t amused for long.

![]()

In a candidate, Lego typically looks for someone with a bachelor’s degree in either an art-related field (architecture, design), or engineering (mechanical, aeronautical, structural). They also expect a candidate to have some level of 3D modeling experience with programs like Maya, 3ds, AutoCad, and SolidWorks; this prepares them for the work they’ll be doing on Lego’s custom-built computer-aided design platform. Lastly, a strong portfolio showing off a variance of Lego skills is a must.

At 23 years old, Andrew Johnson, a DePaul University History major, was the youngest master model builder ever hired by Lego. Here’s his application video:

He was selected to participate in the interview cycle, an “intense, three-round” process in which competitors are not told what they’ll be constructing in advance. Over three rounds, Andrew re-created a Picasso sculpture, built a small-scale model of Dr. Seuss’ Lorax with a mere 20 bricks, and, in the final 45-minute phase, whipped together a violin and harmonica, securing his dream job. He shares one of the methods he used to prepare:

“I don’t buy the kits that come with instructions. I would just buy several of those big tubs, dump them out and start with a picture of something in my head. I can’t remember the last time I used instructions for anything.”

For those who seek more intensive preparation, Lego also offers an MBA program — Master Builder Academy, that is — that provides the “skills, design secrets, and advanced building techniques used by the pros.” Disclaimer: graduating from this academy does not guarantee you a job at Lego. Paul Chrzan, a 40-year-old master builder from Connecticut, offers advice to aspiring students:

“I tell people just build, build, build. Just keep playing with the bricks. Don’t build the house and the spaceship. Build your family pet. Build a family portrait. Go beyond what people usually do with the bricks. Because that’s what we do.”

Lego also employs several in-house designers, who visualize sets and new blocks, and it’s fiercely competitive to get hired. When a position opened up in Denmark, people flocked from around the world to compete for it — a 46-year-old entertainment executive from Australia, a military veteran from Los Angeles, a furniture designer from Indonesia, a Scottish medical engineer — and all agreed the process was “brutal.”

Lego Certified Professionals

Dirk Denoyelle with his Lego mosaic, “Beggar”

An even more selective crew, Lego certified professionals (LCPs) are full-time, freelance Lego artists who are “officially recognized by the Lego group as trusted business partners.” Currently, there are twelve of them in the world.

Essentially, these twelve are international Lego “ambassadors;” they are not Lego employees, and don’t get paid by the company, but enjoy a business to business relationship with them. Lego endorses their skills and gives them access to buy bricks in bulk; in return, they get to advertise the incredible works of art these individuals produce. As freelancers, LCPs are hired by corporations, brands, and private individuals to make custom sculptures, but a few are also highly respected artists who display their work in galleries across the world. Generally, they can make better money than master model builders, and have more freedom in their project selection, but since they are freelancers, this is contingent on how much work they put into it.

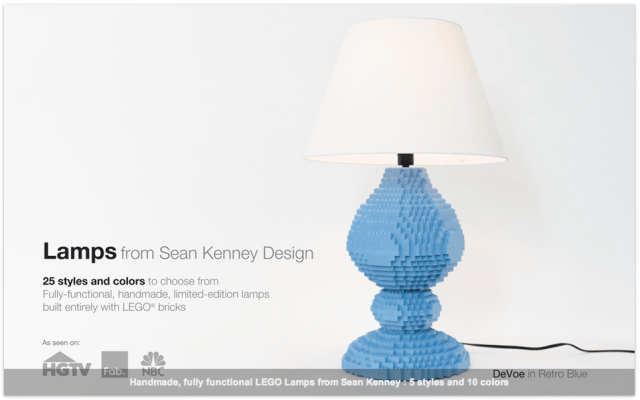

The concept of independent builders being endorsed by Lego was the brainchild of Sean Kenney. Once a disgruntled web designer for Lehman Brothers, Kenney left his job in 2003 to become a master builder; two years in, he pitched the LCP idea to Lego corporate, and they gave him a shot. Today, he’s a successful freelancer, having received commissioned work with the likes of Mazda and Google.

Kenney says there’s really no “standard process” for becoming an LCP, but admits the best approach is to first spend some time as a master builder at LEGOLAND; about a quarter of all current LCPs went this route. Lego is extremely secretive about what they look for in an LCP candidate, and has released no information about how to become certified. One hobbyist surmises that “if you aren’t already a well-known Lego builder with years of experience,” the company likely won’t consider you.

![]()

Before becoming a Lego Certified Professional, Nathan Sawaya worked as a Wall Street lawyer and pulled in a salary in the mid-six figures. To de-stress after intense days, he’d return to his apartment and fiddle around with Lego bricks; in time, he got pretty damn good. He started a website, Brick Artist, where his friends could submit requests of things for him to Lego-fy: portraits of children, movie characters, animals.

In 2004, on a whim, he entered a contest held by Lego to find the best builder in the U.S.; he won, and was subsequently hired as a master builder. He tucked away $13 an hour — about what he made in two minutes as a corporate attorney. After a few years mastering his craft, he embarked on an independent career with the endorsement of Lego.

Today, Sawaya has two studios — one in Los Angeles, and one in New York. His work has been featured in Times Square’s Discovery Museum, Time Warner Center, and a slew of other exhibits in 17 U.S. states. Routinely, he’ll have three or four concurrent builds going on, and his shops contain over 1.5 million bricks in every color, shape, and size imaginable.

Sawaya with a life-size Lego Conan O’Brien; Brick Artist

Notably, Sawaya has built a 10-foot-tall replica of the Trump Tower in Dubai for Donald himself, and a 4-foot bumblebee for pop star, Ashlee Simpson. He’ll charge anywhere from $2,000 to $100,000+ for his commissioned work, depending on the scope of the project; sculptures may take him two days, or two months. Incredibly, Sawaya claims he makes more money as a Lego artist than he did as a corporate lawyer; equally surprising, he also says his hours are longer.

Other LCPs see similar success. Dirk Denoyelle, a 47-year-old who was once a stand-up comic, says there is “real money to be earned in the Lego business.” He recently sold a commissioned village for $20,000, and routinely has projects lined up.

Robin Sather, Canada’s only Lego Certified Professional, runs Brickville Design Works and sees a steady stream of business and museums: his works include a “giant Egyptian sphinx, dinosaurs, fantastic castles and more.” He attributes his success as a Lego builder to his unorthodox development:

“If your peculiarities can survive your adolescent years, you’re going to be okay. By the time I got out of college into early adulthood — yeah — I was Lego guy, and everyone knew it. I’m a businessman and a Lego builder; my relationships with clients are mostly b2b [business to business].”

Sean Kenney, who the New York Times touts among the “artistic elite” of Lego builders, commissions portraits and sculptures as well, but has expanded in home-ware as well. He’s recently released a series of functional Lego lamps that make IKEA look like child’s play, and has been widely praised for his innovation by Good Morning America, NPR, and The Wall Street Journal.

Source: Sean Kenney

Lego Brokers

Larry Pieniazek is a Technical Architect at IBM by day, and a Lego architect by night. He is neither a master builder nor a Lego Certified Professional, but operates Milton Train Works, a company that produces custom Lego train kits, out of his basement. He’s part of a small but faithful contingency of people who run unaffiliated freelance businesses on the side. Many of these folks have day jobs, but consider Lego building more than just a hobby.

Pieniazek is a wealth of knowledge; he knows everything there is to know about Lego, it’s major players, and it’s history — and also, it’s secondary market “underbelly.” When he was part of a team contracted by Kellogg to produce a lifesize Tony the Tiger, he found himself in need of 100,000 bricks — many of which would need to be bright orange. Without the wholesale brick access of an LCP, he had to seek out an alternative option.

Courtesy of Larry Pieniazek

He turned to an community of online “brick brokers,” a group of about 3,000 sellers who buy sets and part them out, capitalizing on builders’ independent needs. Pieniazek estimates “about 10%” of these sellers make a full-time living this way.

He also says there is a customized market for just about anything Lego: pieces, sets, printed designs, and paints. One custom set, Brickmania, even raised a $53,000 Kickstarter fund to produce tank accessories, artillery, and customized “Minifigs” (the little Lego men) who don camouflage and enviable mustaches.

Source: Daniel Siskind (Flickr)

These are likely pieces PC-friendly Lego would never produce, but have developed a considerable demand from adult fans of Lego. Lego Certified Professionals would never be able to do things like this, says Pieniazek:

“Part of their agreement with Lego stipulates that they can’t produce any competing sets that may be at odds with the company. As unaffiliated builders, we have a little more freedom to make the stuff Lego wouldn’t dare to, which is fun.”

![]()

On the fringe of the Lego frontier are the “speculators” — those who anticipate the desirability of a new set, buy a few dozen, hoard them, then sell them off at a considerable profit when they go out of production.

These speculators, like other toy profiteers, sell their stock online or at conventions; good ones are particularly apt at predicting which sets will be hot years down the line. Pieniazek tells us Star Wars sets always “appreciate nicely,” and he should know: he recently flipped a “10030 Imperial Star Destroyer,” originally a $300 set, for $999. His set could’ve gone for as much as $1,500, he says, had it not been water-damaged.

Pieniazek insists that’s nothing: “Cafe Corner,” a highly desirable set produced in 2007, originally sold for $139.99; today, a pristine, sealed set can fetch $1,500 — nearly a 10x profit. “There are dozens of sets, if not hundreds, that are good for 2x-3x; most any Star Wars set 5 years or more old is good for at least 2x,” he adds.

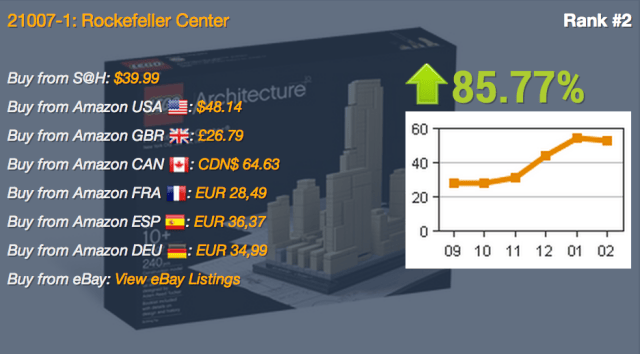

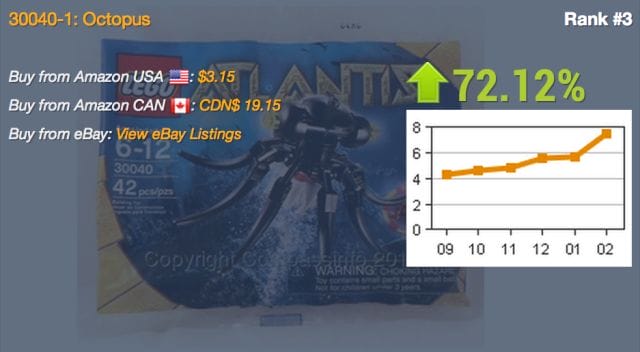

Brickpicker.com is a Lego investment site, specifically crafted for brick brokers to navigate the market. The site offers pertinent financial advice — “Lego Disney Princess Part 2: Will the Clock Strike Midnight on Your Investment?” — and provides an intricate ranking system that “utilizes licensed eBay Terapeak data to show the LEGO investor popular trends in the secondary market.”

Below, we’ve included the three Lego sets with the highest price increase over the past six months (according to Brick Picker’s data):

Data via Brickpicker.com

A variety of other sites (bricklink, brickset) exist, which catalogue every existing Lego set from the early 1960s to present, and dole out standard market rates for collectors and sellers. Bricklink alone lists 279 million items, ranging from Indiana Jones mini figures to tiny door hinges.

Lego as an Art Medium

Source: Jeremy Schultz

For those who’ve made a living with Lego bricks, money isn’t paramount: it’s more about pushing the limits of creation and pursuing something they love. True fans recognize that Lego transcends far beyond a mere toy, into the realm of art, says Pieniazek:

“Lego is a medium: we have a palette – it’s shapes, arrangement of shapes, the colors they come in. It’s as pure of an art form as can be. And like any art, the key to good building is having a system in place, knowing how elements interact. Lego is truly the best building system ever invented; everything works together in so many serendipitous, unintended ways.”

Upon viewing Nathan Sawaya’s “Art of the Brick” installation at Discovery Times Museum, New York Times art critic Edward Rothstein shares a similar opinion:

“In its pure form…the Lego block is at once the least technological toy around. But in another way, it is also one of the most technological, technological in the original sense of the word, alluding to craft and mastery — techne — the art of making.”

In the end, Pieniazek supposes we’re all makers piecing together the bricks of life. Some take this more literally than others.

This post was written by Zachary Crockett. Follow him on Twitter here, or Google Plus here.