“When I was a kid in junior high school, I picked up Tolkien’s The Hobbit, and kind of flipped out. I’ve always wanted to live like a hobbit.” (Dan Price, “Hobbit Hole” Dweller)

![]()

Twenty-five years ago, Dan Price found himself at one of life’s many crossroads.

A freelance photojournalist, his work had placed him in six different states from 1980 to 1990; with a mobile lifestyle and an uninspiring salary, he struggled to support his two small children. For a while, he and his family settled in Kentucky, but a high-interest mortgage rate and “an endless stream of bills” put pressure on him financially. Around the same time, his marriage began to fall apart.

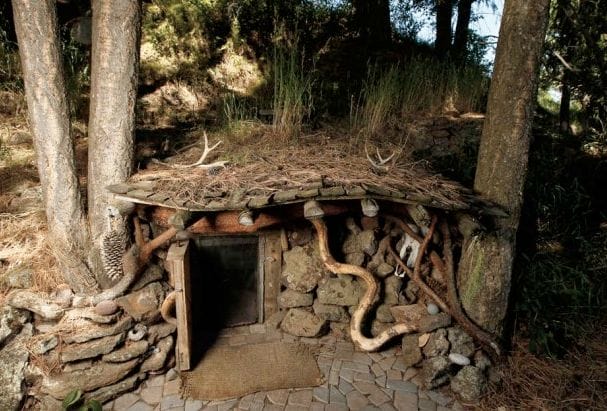

Dan helped his family transition back to Oregon, where he and his wife were from originally. Then he took to the state’s remote Northeast on his own, wandered to the edge of town, and built himself a “Hobbit Hole.” For the last decade, he’s been living underground in the 80-square-foot space built into the earth.

The “Hobbit Hole”

Image via Dan Price

Around the time his marriage dissolved, Dan read Harlan Hubbard’s Payne Hollow: Life on the Fringe of Society, a book chronicling the author’s frugal existence in a shanty along the Ohio river in the 1950s. Dan got deep into Transcendentalism and living minimally, and began questioning the traditional “white picket fence” lifestyle. These ideas were resonating when he arrived in the small town of Joseph, Oregon in 1990.

Here, he found a vacated pasture, contacted the owners (who operated a small farm nearby), and offered them a proposal: he’d care for and clean up the land in exchange for having a quiet place to reside on the 2-acre lot. They agreed, and to this day Dan pays them $100 a year for the privilege of living there.

Before working as a photographer, Dan was a “ski bum” who built houses in Idaho’s Sun Valley, so he was familiar with basic construction methods. With free reign, he embarked on a 15-year “experimental cycle,” building an array of small structures on the land:

“I didn’t know what I wanted at first. I had a tipi, a 9X12 red willow hut, mountain tents, and a 6X10 beach style shack before building the current place. All buildings were constructed with discarded and found lumber. Most cost me under $100 to build.”

Then, with $75 of scrap wood, Dan constructed the home he’d live in for the next ten years.

Image via Dan Price

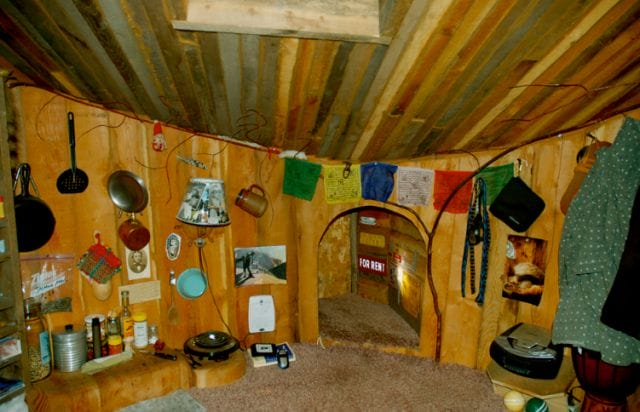

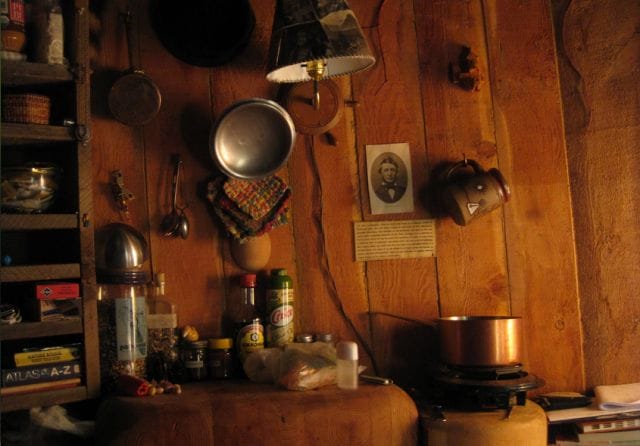

From the surface, all you can see of Dan Price’s abode is its tiny, doggie-sized front door and a small stone patio around the entry. The shelter’s walls are constructed from 2×8 pine boards, their facade enforced by unmortared local stone. the roof, buried in moss and rotting leaves, is also wood, sealed with heavy plastic.

Inside is a circular space with an 8-foot diameter — about 50 square feet total — that Dan compares to “a hot tub shape sunken into the ground.” There is no running water, no refrigerator, and no bed — just a hot plate, a sleeping mat, and an assortment of trinkets and books. The one luxury Dan enjoys is underground electricity, which provides him with a few interior lights and a charging dock for his phone.

Image via Dan Price

Image via Dan Price

In an adjacent space, he’s built an outhouse with a composting toilet. “After about two years,” he says “all the waste turned to soil; I put it on my trees now.” He practices the art of “humanure,” or recycling his poop into fertile soil that can be used for gardening, planting trees, and revitalizing local flora.

He has also constructed a small shower which uses water from the nearby river, a studio shed where he works on art and writes, and even a natural sauna using rocks, fire, and steam, similar to a North American Sweat Lodge.

Living on $5,000 Per Year

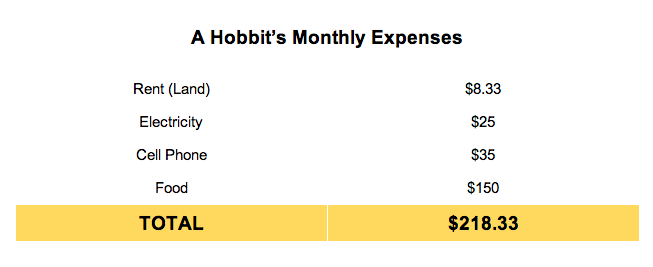

Dan’s living expenses in the “hobbit hole” are minimal: $25 per month for electricity, $35 per month for his cell phone plan, $5 per day for food, and — of course — the yearly $100 fee to rent his plot of land.

Altogether, Dan says he lives on $5,000 a year.

To match his unorthodox living situation, he’s had a number of unorthodox odd jobs, which he says have given him “a broader view of the way the world works:”

“I’ve been a logger, a farmer, a heavy equipment operator, a carpenter, a dishwasher, a maid, a photo lab tech, a short order cook, a busboy, a gardener, a cemetery caretaker, a ski shop employee, a surf shop employee, an artist, a news photographer, and — probably the biggest job ever — a father. I have never had a job where i had to sit all day. I know I could not do that.”

But Dan also has a steady gig that “pays the bills:” His self-published “journal-zine,” The Moonlight Chronicles, has earned him an “underground” cult following, and sales through his website and Amazon amply cover his expenses, he says. The journals elaborate on Dan’s philosophies and lifestyle, and are a mixture of hand-drawn illustrations and musings; over 20 years, he has published 77 issues.

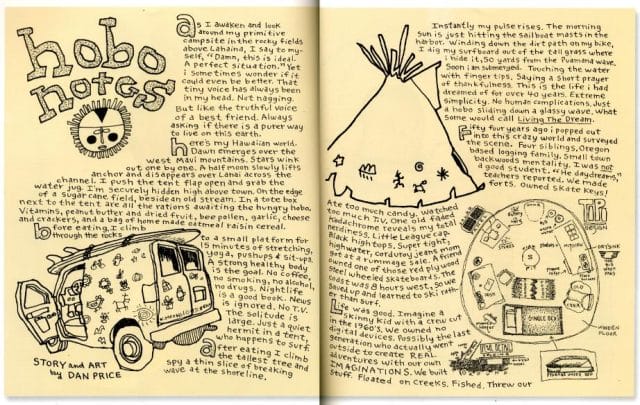

A compilation copy of his work in book form has a 4.3 out of 5 rating on GoodReads; one reviewers writes, “A true original. Dan Price lives a life I didn’t know was possible in the USA. Very unique.” The book aptly depicts Dan’s lifestyle, and includes an array of original artwork:

Excerpt from Dan Price’s Moonlight Chronicles (2012).

But Dan only lives in his “Hobbit Hole” six months out of the year. During the harsh Oregon winters, he hops on a cheap flight to Hawaii, lives in a minivan, and surfs.

Each year, a month before heading to Hawaii, Dan starts his search for a van on Craigslist, with a budget of $2,000. He usually arranges the sale perfectly, so that he’s able to meet the owner at the airport and drive with her straight to the DMV to make the transaction. Once the van is in his possession, Dan rips out the seats and makes it his home for six months. This way, he says, he’s able to live both minimally and cheaply:

“Living in the van is similar to the hobbit hole in that it is a very tiny space, which I prefer. Everything is within arms reach. It becomes my sanctuary away from all the noise, people and weather. Some people wonder how I can afford to live in Hawaii for half the year, but all I’m paying for is food and gas.”

Portable “Hobbit Hole” in Wiamea, Hawaii; image via Dan Price

Interior of Dan’s live-in van; image via Dan Price

He lists his expenses as a “few throw pillows for a buck each at Salvation Army, a sheet and pillowcase for another buck, and a pile of good books for 25 cents each.” Generally, he’s able to stick to his $5 per day budget for food, and doesn’t spend too much on gas as he stays put when he finds a good surfing spot. At the end of each trip, he re-installs the seats and is almost always able to Craigslist it for a full return.

While Dan admits that “most hobbits probably don’t surf,” the surfing lifestyle is on par with his minimalist philosophy.

The Merits of Living on Less

The less Dan Price has, the more he “appreciates all the little gifts in life.” He’s thrived on living by the “less is more” adage, and now that he’s attuned himself to the hobbit life, he says he has no desire to return to his old ways:

“I couldn’t live in a regular house ever again; it’s too much space, and too extravagant. I like tiny spaces. There’s just this wonderful feeling of coziness… almost a womb-like feeling.”

Earlier on, whenever he had the urge to downsize or rid himself of a luxury, Dan’s first reaction was that he couldn’t do it. But once he learned to “take the plunge,” he found that he was rewarded with more clarity and happiness.

“I started dragging less and less baggage around behind me. Imagine having only a few bills that are on autopay and that don’t get your heart to racing when your think about them. Imagine having no debt. No one owns me or my time. So I can go do as I please and try to help others whenever I can.”

This post was written by Zachary Crockett. Follow him on Twitter here, or Google Plus here.