San Francisco Voter Guide June 2008

Chris Fedor is a 27-year-old San Francisco resident with a sober demeanor and a strong sense of civic duty. As a rule, he dislikes ballot measures—pieces of legislation that live or die by popular vote.

“They put the most important decisions into the hands of the least qualified people,” he said.

Which is why, this year, Fedor decided he was going to put together a voter guide to help ordinary people decide what the city should do on issues impacting policy and budget. But his plan didn’t involve researching each measure, choosing a stance, and then foisting his inexpert opinion on others. Fedor is the first to admit he is not a policymaker—he’s a programmer.

His guide advises voters based on a simple algorithmic approach: it takes in the opinions on a measure published in the information pamphlet the city mails to every registered voter before elections, and tells you to vote with whichever side is most sparing in its use of ALL CAPS.

According to Wikipedia, “netiquette generally discourages the use of all caps when posting messages online. While all caps can be used as an alternative to rich-text ‘bolding’ […] repeated use of all caps can be considered ‘shouting’.”

Fedor thinks the proportion of all capital letters is a good litmus for the emotional timbre of an argument. “The theory being that no matter what the issues are, the most hysterical side is probably incorrect,” Fedor laughed.

Fedor intended the guide as more of a political statement than a practical tool, but then he tested his program on the information pamphlet for this year’s San Francisco ballot. He flipped through the guide and concluded that the guide was uncannily “correct.” It tended to pick positions he would have (based on the pamphlets) selected himself.

So he tried it on the pamphlet for last year’s ballot, and the same thing happened. Had he unwittingly stumbled on something useful?

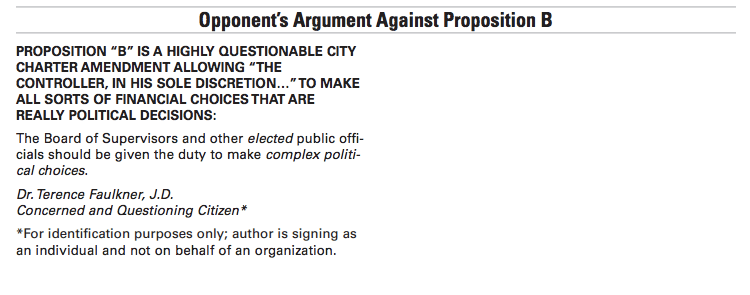

Then he noticed something: an uncanny percentage of the all caps-heavy opinions were written by the same person: one “Terence Faulkner, J.D.”

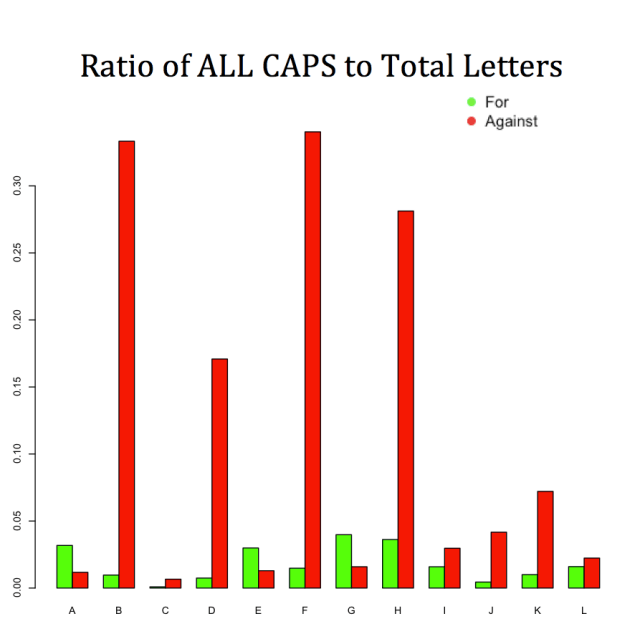

The ratio of capital letters to total letters on either side of a ballot measure. Acronyms excluded, rebuttals and arguments weighted equally. “Each of those red peaks is a measure where Terence Faulkner authored the only opposing argument.”

Faulkner wrote four of the opinions published in this year’s information guide (out of twelve possible), and one on last year’s (out of four). He signs a different credential to each of them. In one he is a “Supreme Court Plaintiff”, in another a “Republican Central Committeeman”, in another a “1999 Member of State of California’s Certified Farmers Market Advisory Board,” and in another a “Concerned and Questioning Citizen.” He apparently has a penchant for all caps, and seems to disagree with Fedor on just about every political point possible.

The “J.D.” after Faulkner’s name went some way in explaining things—all caps is a commonly used convention in court documents. “He basically broke my algorithm,” Fedor opined. “But,” Fedor said, “some of his arguments were pretty unusual.”

For example, San Francisco Proposition B would link public transportation funding to the city’s population, to improve more heavily-taxed infrastructure. Faulkner’s main argument against the proposition was brief and mostly capitalized—168 out of 317 characters were formatted in all caps:

San Francisco Voter Guide, 2014

But his rebuttal to the proponent’s argument, while more conventionally formatted, was also more “unusual”:

REGARDING POLITICAL SORCERERS AND GREEDY HOUSING DEVELOPERS:

Giacomo Casanova, in The Story of My Life, tells of being 8 years old in Venice with a nose bleeding problem in 1733:

Marzia, my grandmother…took me in a gondola…to Murano (Island)….Stepping out of the gonodola, we entered a hovel…(with) an old woman holding a black cat (speaking)….the Friulian tongue….(M)y grandmother gave the witch a silver ducat, whereupon the crone opened a chest…put me inside it, and closed it….I was finally extracted; my bleeding stopped….(S)he rubbed my temples with a sweet-smelling unguent and…told me my hemorrhage would continue to subside so long as I did not tell…what she had done to cure me…”

Like the witch, there are many political sorcerers and housing developers here in San Francisco who want to hide from the public their massive overbuilding of the City, causing terrible traffic, parking, and auto accident problems — also causing awful demands for municipal services. The public harm can be hidden for awhile.

Their real goal is to make greedy developers as much money as possible, leaving the City’s residents holding the losses.

The City Charter — the developers demand — should be amended to promote their profits.

As an older and wiser Casanova later wrote:

“Sorcerers have never existed, but their power has, for those who have the talent to make others believe they were sorcerers.”

Dr. Terence Faulkner, J.D.

United States President’s Federal Executive Awards Committeeman (1988)

“I can’t tell if this is an elaborate piece of performance art,” Fedor said. “I mean, is this James Franco?”

Terence Faulkner is Not Here to Entertain

Terence Faulkner’s bio on the SF GOP website

Terrence Faulkner is not an elaborate performance artist. He’s a 70-year-old San Franciscan with a sober demeanor and a strong sense of his civic duty. As a rule, he’s not a fan of ballot measures either, which is one reason why he’s on-record as the official opponent of so many of them this year.

“Ballot measures are dangerous,” Faulkner told us. “For one, they automatically allocate money to branches of government whose need might only be temporary. If they ever do run a surplus, they dare not give the money back because if they do they could lose it forever.” This is his reason for opposing Proposition B, above.

Faulkner was born in San Francisco. His father was an official in the Parks and Recreation department. His great grandfather was “originally from Ireland,” as Terence Faulkner wrote in his rebuttal to an argument in favor of Proposition D:

“He became an American citizen before the New York Court of Common Pleas in 1856, voted for Abraham Lincoln in 1860 and 1864 because he didn’t like slavery, married a girl in New York, but lost her and their baby in childbirth […] [then] came to San Francisco by way of Panama in 1866, working at Selby’s preparing gold and silver bars for the Old San Francisco Mint.”

Faulkner says that when signing his arguments, he lists his various credentials “depending on what might be relevant.” “I’ve been involved in many things,” he explained. He received his J.D. from San Francisco Law School. He was the San Francisco Republican Committee Chairman from 1987 to 1989 and currently serves on the central committee.

The “United States President’s Federal Executive Awards Committeeman (1988)” title refers to when he was on an advisory committee to President Reagan, evaluating nominations for 10,000 bonuses to federal employees.

Faulkner was, in fact, a “Supreme Court Plaintiff” in Renne v. Geary (1991) and Mark v. Corwin (1994). He describes the cases he litigated as “typical 1st Amendment things—free speech is one of the ways you can make it to the Supreme Court without having done anything terrible.” Unsurprisingly, they had to do with suing city election officials over the regulation of voter information pamphlets.

As one can easily tell from speaking with him, Faulkner definitely is a “Questioning and Concerned Citizen.” He says he’s been writing opinions for voter information pamphlets for about 40 years—as long as citizens have been allowed to author opinions on pamphlets in San Francisco.

He also said that this policy exists because of a lawsuit he and his colleagues brought against the city in the 1970s. So it’s no small wonder that Faulkner is a relative expert in writing opinions for voter information guides. “A lot of people don’t even know how to submit an opinion for publication,” Faulkner says. “In fact, most don’t.”

The Process

Here is how a passage from Casanova’s biography, as quoted by Terrence Faulkner, ended up in this year’s voter information pamphlet:

1. He drafted it up within the word limit (300 for unpaid arguments), and submitted it to the San Francisco Department of Elections by August 14th. Mail or delivery required.

2. He also signed a form swearing that he was in fact an opponent of Proposition B — i.e. stating under penalty of perjury that he was not a troll, and got that in before the deadline.

3. Neither the mayor, the board of supervisors, nor the person who filed a referendum petition (if striking the measure down were to repeal an existing act of legislature) submitted an argument against Proposition B. Faulkner’s argument was selected out of a lottery of every submitted argument against Proposition B that qualified.

Technically, the Casanova quote surfaced in a rebuttal. But when he won the lottery to be the official opponent of the proposition, he also won the right to the rebuttal, or to assign the writing of the rebuttal to somebody else. Then, he formulated his response to the Sierra Club’s argument in favor of Proposition B, quoted Casanova in it, and submitted it to the department by August 18th.

“I had a couple people read the Casanova one before I submitted it,” Faulkner told us, “and they thought it was interesting. It’s one of the cleaner stories in his autobiography.”

There were a few more requirements to get into the lottery: organizations authoring opinions have to have an officer who is also a San Francisco voter sign. Because Faulkner’s an individual, and himself a San Francisco voter eligible to vote on Proposition B, he’s set. Also most authors, when they mention another person in their argument as an opponent or ally, have to either obtain written consent from that person or cite a “newspaper of general circulation” reporting that this person holds this position. Faulkner doesn’t need to deal with this because he doesn’t implicate Casanova as either a proponent or an opponent of the proposition, and because Casanova died in 1798.

Casanova hasn’t signed a consent form in a couple hundred years.

An interesting thing about all this: If Faulkner exceeded the 300 word limit in his original submission, the city returned his draft for deletions and told him to resubmit it by the deadline. Otherwise, the department printed his argument “exactly as submitted.”

The only exception is when, during a “public inspection” period in which the arguments are public but not yet submitted, a voter seeks a court order requiring the material be amended or deleted. If they successfully demonstrate the material is “false, misleading, or inconsistent with state or local election laws, and that the amendment or deletion will not substantially interfere with the printing or distribution of the Voter Information Pamphlet,” then the court will edit or delete the argument. This generally does not happen.

Another interesting thing about this whole process is that it happened four times this year—Faulkner won four lotteries. This means that his odds must be considerably better than that of winning the SuperLotto Plus state lottery. Neither the mayor nor any of the supervisors authored dissenting arguments (they unanimously voted to put many of these measures on the ballot), and none of these measures was a referendum, which means the dissenting opinion on all of the measures was selected by “lottery”. If Faulkner submitted opinions on every ballot measure this year, his success rate implies that there are an average of three opposing opinions submitted per ballot measure.

Faulkner says he didn’t do this. He listed six measures that he did submit opinions on, and said their might have been “a few more.” If had only submitted six, his success rate implies that there were an average of 1.5 opposing opinions per measure — i.e. that his was the only submission in some of these lotteries.

The Libertarian party, whose opinions are sometimes signed by an individual going by the name “Starchild” (who the author believes she met at a festival in 2011, camping on top of a houseboat), used to win the rights to publish the plurality of opposing arguments. According to Faulkner, the Libertarian party had been exploiting a loophole that gave them an advantage in the lottery:

“Previously,” a San Francisco Department of Elections representative said of the loophole, “one author would submit identical arguments for or against a measure for the lottery, and that person would have higher chances of getting selected.” This happened several years before the Board of Supervisors enacted new legislation this August, limiting authors to one argument per measure. Faulkner attributes his arguments’ predominance on this year’s ballot to this policy change.

Now, Faulkner and the Libertarian Party are just about tied:

***

Unusually opinionated people, like Terence Faulkner, exist in many cities, and especially large ones. But in most cities as large and politically active as San Francisco, more ballot measures receive more robust and diverse opposition than just Faulkner and Starchild. And this, Fedor said, is a problem.

Fedor researched the issues on this year’s ballot much more thoroughly before voting. He actually ended up siding with Faulkner on a few counts. After all, they both dislike ballot measures. “With propositions,” Fedor said, “it’s often very difficult to make an informed decision, even for an involved citizen. In which case I think the responsible, reasonable approach is to abstain or vote ‘no’.”

This is what voter guides are for—laying out the issues in a way a voter can understand, and providing all the information they would need to be an informed voter. But that breaks down if so few people care about certain measures that one or two personalities can take over large portions of the guide.

Our next article examines the similarities between Henry Ford and Donald Trump. To get notified when we post it → join our email list.

![]()

Note: If you’re a company that wants to work with Priceonomics to turn your data into great stories, learn more about the Priceonomics Data Studio.