I wrote Mr. Tambourine Man, that little man ain’t nothing but a thief. But I don’t care at all I was destined to be poor, destined to stay in this city.

“I Wrote Mr. Tambourine Man”, John Craigie

***

How do songwriters make money? It depends on who they are.

If the songwriters are pop writers like Max Martin or Ryan Tedder, they carefully craft a hit single, find a boy band or celebrity diva to sing it, and rake in the millions. The music publishing company takes a cut, and the performer responsible for the recording, and the record label. But if the hit is a hit, album sales, and streaming, and radio plays, and use of the song in movies and television and ads are usually significant enough that the songwriter makes bank.

If the songwriters are indie musicians like Rennie and Brett Sparks of the Handsome Family are, things work a little bit differently: they write their own music, tour and record albums themselves to promote it. On top of that, they take what they can get in royalties on their compositions.

Because many people find The Handsome Family’s songs strange and captivating, those royalties have become pretty significant in recent years. In 2014 one of their old songs got picked up as the theme for the HBO show, “True Detective”. In 2014, the famed “singer-songwriter-whistler-violinist-etc.” Andrew Bird released an album entirely of covers of their songs. Those covers do more than just raise the band’s profile — Rennie and Brett make money off of them.

“Everything is percentages of percentages,” Rennie writes in an email. “[But] we get paid when our song is covered by other artists and we get paid when their cover is licensed.”

It all has to do with the business end of songwriting — the way songs get sold and divied up, and the way copyrights and royalties get managed.

Early Music Publishing

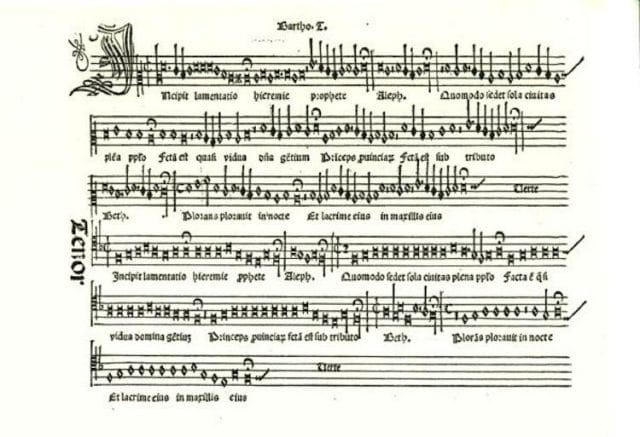

16th century music printing, by Ottaviano Petrucci

Before a concept of copyright or intellectual property emerged, music publishing was literally just the printing and distribution of sheet music. In late medieval Europe, a printer could pay the monarch in exchange for monopoly rights over the printing and the sale of a work. This protection was called a “crown privilege”, and could be applied to both text and music.

As Martin Kretschmer and Friedemann Kawohl write in Music and Copyright,in 1498, the printer Ottaviano Petrucci petitioned the Doge (duke) of Venice for the exclusive rights to print any music for 20 years. Because there are no known examples of printed music from other Venetian printers until 1520, historians think his petition was successful.

These protections were printing rights, given to printers, not artists. Up until the end of the 18th century, the author of a printed work — its writer or composer — typically handed it over to a publisher in exchange for a single, one-time payment. In the early 19th century, things began to change, in a wave of laws, passed in revolutionary France, Prussia, and the UK. Under these new laws, the creator of the work became the central copyright holder. Statutes of protection were pinned to the author or composer’s life span, and a work needed to be original to the author in order to be protected.

Protections also started to extend beyond printed material. As German jurist Eduard Gans wrote in 1836, “In performances the author exposes himself to the risk of disapproval and thus the dramatic author should be able to decide every time anew to which public he presents his work.” Most of the great classical composers and dramatists of the time made their money, and their names, off of performances. These new laws granted artists performing rights: authority over when and how their works were performed.

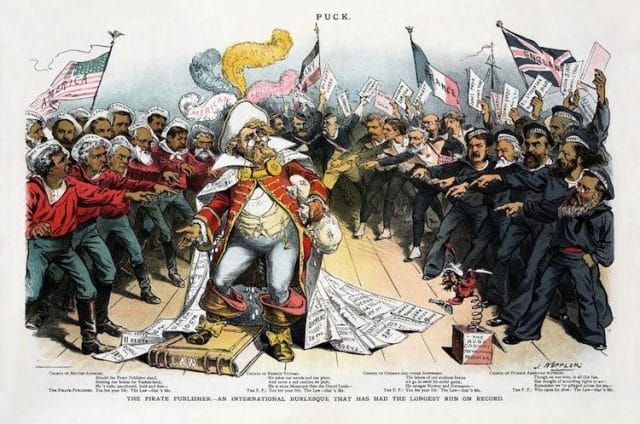

“Behold the Pirate Publisher stand,/Stealing our brains for Yankee-land”; From Puck, 1886, restored by Adam Cuerden

The United States was a little behind in these reforms: printed music wasn’t protected in the United States until the Copyright Act of 1831, and even then, performing rights weren’t covered. More importantly, copyright laws in any country only applied to works created within the country’s borders, and not to any foreign works. Thus, British works could be copied and sold by anyone in the US, Germany, France or Holland, legally, and works from those countries could be reproduced in the UK. As the global economy grew, overseas piracy of printed documents did also.

In 1878 Victor Hugo, author of Les Miserables, founded the Association Littéraire et Artistique Internationale with the object of creating an international convention “for the protection of writers’ and artists’ rights.” Eight years later, this resulted in the Berne Convention — an international agreement on copyright.

The original signatories of the Berne Convention were Belgium, France, Germany, Haiti, Italy, Liberia, Spain, Switzerland, Tunisia, and the United Kingdom. One of the biggest features about the Berne Convention is that it assigned copyright to creators by default, as soon as a work was “fixed” — written or recorded — without needing to be submitted or declared. The United States, wanting to still require people to register for copyright, entered other international agreements without this clause before finally coming around and joining the Berne Convention in 1989. There are 168 states participating in the Berne Convention, today.

Other Rights and the Hit Factory

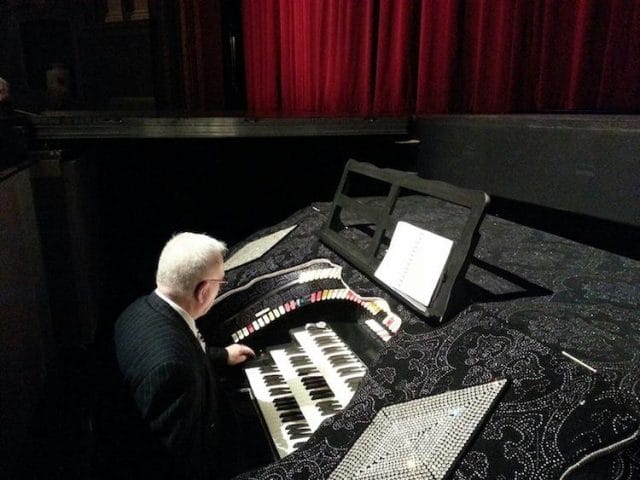

A theater organ for silent film accompaniment

A copyrighted song consists of the music, “as written”, and any accompanying lyrics. If the composer and the lyricist are two different people, together they are considered the author of the work. Both the lyrics and the music are protected.

Once a copyright is granted, its holder has the option of licensing the work out to others for distribution, often in exchange for compensation. One common option is to work out a royalty agreement, by which the copyright holder gets a cut of the profits from each derivative work — in this case each performance or article of sheet music. Printing rights and performing rights were the first of several different ways to license out music, as music was soon to find even more forms.

At around the same time Victor Hugo was campaigning for the Berne Convention, Thomas Edison invented the phonograph. Suddenly, sound could be reproduced and distributed in recorded form. This (and, oddly enough, the player piano) gave rise to mechanical rights, first codified in the U.S. Copyright Act of 1909. Mechanical rights license the distribution, reproduction, and modification of sound recordings and other ‘mechanical’ copies of music.

A few decades later, “talking pictures” made their ascent. Movies used to be “silent”, dialogue would appear between scenes on title cards, and musical accompaniment was usually provided by a live, in-cinema piano player. But “talkies” were synched with recorded dialogue and synchronized scores. Thus came synchronization rights — authority over when a song appears synched other media (as in movie scores, television, and commercials.) Sampling rights entitle copyright holders to compensation when their work is included in a collage, as in a DJ mashup.

…Baby One More Time, performed by 16-year-old Britney Spears, written by Max Martin

The present system rapidly took shape. Music publishing companies provide capital to promising songwriters in exchange for a cut of their future royalties on particular songs. Eager to see their investment return, the publishers then promote these songs to popular artists who might want to cover them, either in a recording or on stage, and track down owed royalties on the songs and manage their licenses — whether mechanical, synchronized, sampling, print or performing. When somebody covering, or synching, or sampling a song, does not pay for a license, they can be sued. Record labels basically do the same thing, but for a sound recording. They pay publishers for the license to make the sound recording, and then issue their own license for whenever someone wants to use that particular recording. Synchronization and sampling royalties get paid to both the label and the publisher. Some companies do both — purchasing the copyrights of both a song’s composition and sound recordings of it.

If you want to post a YouTube video of yourself playing a cover song, you’ll need a mechanical license — to make an audio recording copy of the song, and a synchronization license — because your recording will be synched with video. That means figuring out who holds the copyrights and obtaining those licenses. There are agencies that specialize in this.

This system has resulted in other pretty particular specializations, which is the secret to the present day pop industry. You end up with songwriters who might have production or performance careers of their own, but are also the ultimate creative source of most pop music: Ryan Tedder (who co-wrote Beyonce’s “Halo”, Leona Lewis’ “Bleeding Love”), Max Martin (The Backstreet Boys’ “I Want it That Way”, Britney Spears’ “…Baby One More Time”). On the other side of the coin are the celebrity performers who are essentially sparkly media vehicles for songs written, arranged, and produced by other people.

You also end up putting artists like Paul McCartney in some pretty awkward situations. The publishing rights to the Beatles’ Northern Songs catalog — which contained practically every Beatles song — became valuable enough in the 1960s that the Beatles and their publisher decided to trade it as a public company to save on capital gains tax. The publisher then sold his shares to a company, ATV, which wrested control of the catalog away from the Beatles. The ATV catalog, including the Beatles songs, was bought at auction by Michael Jackson in the 1980s (for £24,400,000). Then in the 1990s, Jackson merged his catalog with Sony/ATV. Paul McCartney, a former Beatle, now has to pay royalties to Sony/ATV every time he plays a Beatles song, even though he wrote and popularized it himself.

This juggernaut of a system has made many people rich. But not every musician wants to fit into that system. Some musicians want to make pop hits. Others, it seems, just want to make music. For those in the latter category, things work a little differently.

Such Handsome Folk

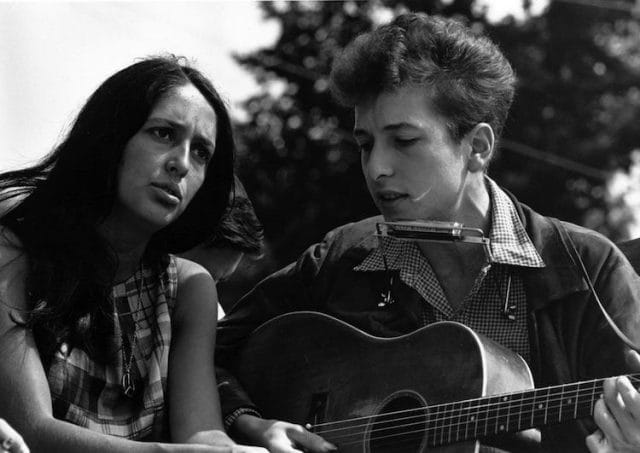

Brett and Rennie Sparks of the Handsome Family; photo Jason Creps, 2012

“We really have no plan and never have had one,” Rennie Sparks of the Handsome Family says. “We just sit around and write songs because it gives us great pleasure to finish a good one. Then we release records and we tour and play live in order to support that habit of loving to write songs.”

Rennie and her husband Brett are indie musicians. They’ve been writing songs and playing together since 1993. Rennie usually writes the lyrics, Brett the music. Their band, The Handsome Family, has been signed to small record labels. And even though Andrew Bird has said in concerts that the two of them are some of the greatest living American songwriters, they’ve never been approached by a music publisher, so they manage all of their own licensing and royalties. This means more work for them, but it also means they don’t have to share their royalties with a publishing company.

This freedom also means they can write some very weird music. As a reviewer wrote of them in NME, “Each song is like an abridged Flannery O’Connor story read aloud by Johnny Cash, hovering somewhere between the metaphysical and the mundane.”

“They do what the best songs can do: Condense all this meaning into the fewest possible words,” Andrew Bird has said in an interview. “[Their writing] is so subtle and strange, it gives the listener credit for having imagination.” From their song, “Drunk by Noon”:

There once was a poodle who thought he was a cowboy

He lived in a cage the size of his thumb

Though his white horse was a box of toothpicks

He galloped around until hit by a car

Sometimes I flap my arms like a hummingbird

Just to remind myself I’ll never fly

Sometimes I burn my arms with cigarettes

Just to pretend I won’t scream when I die

“[Our songs are] not, ultimately, about anything,” Rennie says. “They are a thing unto themselves. A lot of my thoughts, dreams and experiences go into them, but the end result is not a direct sum of parts. Art is mystical not mechanical.”

This mystique has not made them pop sensations. Their songs don’t get a lot of radio play, outside of niche college stations. They perform smallish venues, and their shows don’t always sell out. But their idiosyncratic style has won the hearts of other artists, and those artists have evangelized them to new listeners. The Handsome Family gets paid whenever someone covers their music, and whenever a cover is licensed (for synchronization, download, streaming, or performance). Andrew Bird’s Handsome Family cover album, Things are Really Great Here, Sort Of (which Rennie describes as a “great honor, and a breathtaking thing to hear”), did well. Two of his five most popular tracks on Spotify are Handsome Family songs — one has over one million plays, the other over 2.5. That’s more than four times more plays than almost any song in the Handsome Family’s catalog, as they performed them themselves.

Still from the Season 1 True Detective title sequence

One track of theirs has exceeded the popularity of Andrew Bird’s album on Spotify, however. “Far From Any Road” has over 12 million plays. Released in 2003, the song was relatively unnoticed until T. Bone Burnett, music director for True Detective, selected it as the show’s theme song last year. It came as a surprise to the Sparks, who had never met Burnett nor heard of the show. Rennie has said in interviews that this exposure seems to have translated into a bump in record and ticket sales, and also to more activity across their catalog.

Now they’ve got money trickling in from many different directions. Performing royalties, whenever Andrew Bird covers a song, or anybody covers Andrew Bird covering them (Andrew Bird does have a publishing contract, so these royalties are professionally managed). Royalties on the sales and synchronization of the recorded covers. Synchronization fees from the TV show and youtube. Sales of their own albums, streamed tracks, and shows.

While it’s not been an easy path, nor a particularly lucrative one, it seems that there’s still a place for the strange and personal songwriter in today’s music industry.

“I do think there are a lot of really goal-oriented musicians out there who want to have ‘hit’ songs and definitely write for that,” Rennie Sparks, of the Handsome Family says. “[It’s a] different kind of pursuit. We’d probably be a lot more successful if we thought that way, but in the end it wouldn’t give us much pleasure. So we just do what we do.”

This post was written by Rosie Cima; you can follow her on Twitter here. To get occasional notifications when we write blog posts, please sign up for our email list