The ghost city of Kangbashi

China has been building like crazy. Parallel to rapid, gargantuan urbanization — 300 million Chinese people moved to the city from the country in the past 2 decades — land development and construction has boomed. As Vaclav Smil has noted, from 2011 to 2013, 6.6 billion tons of concrete were used in China — that’s about 2 billion tons more than were used in the United States over the entire 20th century.

But as it turns out, even in China, 6.6 billion tons of concrete might be too much concrete.

Much of that concrete has gone into constructing new, large scale urban projects. Now, many of the buildings in these budding metropolises lie empty. They’re called “ghost cities,” but whereas “ghost towns” are usually abandoned boom towns, China’s ghost cities were never alive in the first place. These towns are still waiting for their boom to happen, either organically, or through intervention of the state.

A Brief History of Ghost Cities

Over the past few years, China’s urban population has grown by roughly the population of Pennsylvania every year. In 1990, 26% of the Chinese population lived in cities. Today the urban population makes up about 54% of the total population. According to current estimates, 15 years from now China’s cities will contain 70% of the national population, amounting to about 1 billion people.

Those urban populations need urban housing. But a lot of the actual construction in China came in anticipation of migration into an area. The typical ghost city is a planned city, and apparently planned quite poorly. “The kinds of population pressures [the ghost city of] Ordos imagined they would have have not come to pass,” Tom Miller, author of China’s Urban Billion: The Story Behind the Biggest Migration in Human History, has said.

How did these urban planners get it so wrong? According to economists, including those at The Economist, this is because of incentives. Large-scale development projects are an unusually easy way for local governments to boost their GDP. The Chinese national government has made expanding its GDP a top priority, setting aggressive growth targets. In China, there are strong incentives to doing what the government wants.

“Who wants to be the mayor that reports he didn’t get 8% GDP growth?” Miller said in 2013. In 2012, China’s target GDP growth was 8%. “If [building is] the easiest way to achieve that growth, then you build.”

Shanghai, a newly expanded, very populated Chinese metropolis (Mstyslav Chernov)

“China is a command economy,” Gillem Tulloch has said, “and the government basically dictate[s] where resources are spent.”

Building a city is unusually easy in China because there are few legal barriers to prevent officials from grabbing agricultural land, uprooting farmers, and “mak[ing] money for themselves and their cities by selling it to developers.”

Developers have been buying and developing land because citizens have been purchasing them as investment properties.

Some of these buyers are following the mythos of urbanization, and the marketing strategies of realtors, believing that these cities would one day populate. But China’s rising middle class has found it difficult to purchase even modest properties in well-populated cities. Residences in ghost cities tend to be cheaper, and in a marriage market where men significantly outnumber women, owning a home is seen as an asset — even if nobody wants to live in it, yet.

In 2010 The Shanghai Daily reported the results of a survey that noted that “most Chinese mothers wouldn’t give green lights to marriages without apartments.” They also quoted an academic who said, “mothers-in-law are the driving force behind China’s unrelenting real estate boom.”

Some analysts have used ghost cities’ existence, and an urban housing price-to-income ratio ranging from 20:1 to 35:1, to argue that China experienced a massive property bubble from 2005-2013. Now that GDP growth has slowed, believers in the bubble are saying it has begun to deflate, which means that property owners in China stand to lose a lot — especially those who own property in ghost cities.

How Many Ghost Cities Are There?

From a Baidu study on ghost cities

The ghost city of Ordos has become quite famous in the past couple years. Or, to be more specific, Kangbashi has. The sprawling, 137 square mile metropolis was planned in 2003 as a subdistrict of Ordos. It was built 16 miles from the preexisting urban center of Dongsheng.

It was thought that Kangbashi would hold over a million people. In 2014, it was said to hold a “lonely” 20,000. That’s like building a city the size of Dallas, and having only a small suburb move into it.

According to Wade Shepard, author of China’s Ghost Cities, China’s strategy towards urbanization is, “‘we’ll build it and we’ll make them come.” From an Atlantic interview of two documentarians working on a film about Kangbashi:

“I don’t think that the government would admit (that Ordos) is a failure. They’re still trying hard to bring people in. The government has moved its officials into the new town, and they’ve also moved some of the city’s best schools into the new town, to try to bring in young people. So high school kids — they have to go to the new town for school now.

There’s a huge campaign underway to occupy the city. They’re basically giving people from the whole region — and Ordos is bigger than Switzerland — incentives to move to the city, or they’re forcing them either by moving schools, hospitals, or other public facilities into the new city.”

According to the documentarians, it seemed to be working. As the filmmakers have said, “When we first went there two years ago, the new city was actually quite empty. When you go there now, it is a lot livelier.”

But Ordos is a high-profile case, one of the best-known ghost cities in the world. The tricky thing is that there are many more, lesser-known cases in China, and it isn’t easy to know which cities are ghost cities, nor how many there are in China. It’s also not easy to determine when a city’s vacancy rates go up, or down, because the Chinese government doesn’t publish vacancy statistics. According to Quartz, “some reporters and hedge fund managers have taken to counting apartments with lights off at night.”

The key to understanding the problem of China’s ghost cities (and thus the national property market) will be knowing where they are. Baidu — a popular Chinese search engine and Internet company, often referred to as the “Chinese Google” — recently published a paper on how to identify ghost cities.

Researchers looked at residential areas on Baidu Maps (analogous to Google Maps), and then looked at the number of regular Baidu search engine users in the area. 100-square-meter areas with fewer than ¼ the average number of Baidu users were labeled “high vacancy.” Cities were then ranked by the proportion of high vacancy space — the ones with the most were put on Baidu’s list of possible ghost cities.

In the paper, Baidu listed, unranked, 20 of the 50 most vacant cities in China. “The reason why we did not show the real rank is that the rank is very sensitive and it may affect the sale of realestate.” According to NPR, the company is looking to sell the rest of their data to real estate companies.

Kangbashi gets a mention in the paper as having a “very high” vacancy ratio: if the city is beginning to populate, like the documentarians claim, it still has a ways to go.

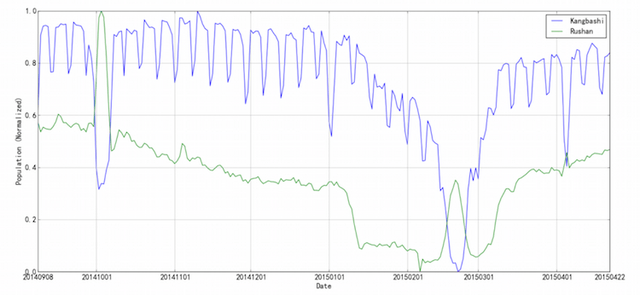

The researchers also demonstrated the utility of their data in tracking more subtle demographic trends. For example: the city of Rushan is also on Baidu’s list. But on Chinese New Year, the number of Baidu users in Rushan spikes, and the number in Kangbashi plummets. This means that, unlike Kangbashi, Rushan’s population might be high-vacancy because it is more of a seasonal tourist town than it is a ghost city. People go to places like Rushan when they have a day off, and they leave places like Kangbashi.

From a Baidu study on ghost cities

Ordos Wasn’t Built in a Day

In urbanization, as in many things, China is exceptional. Most cities in the world are somewhat “natural” phenomena — people gathered around harbors, trading posts, or mines, and then they organized to build the municipal infrastructure to support and accommodate them. Getting people together was the easy part, making sure they had enough space to live in, a safe way to travel through the city quickly, clean food to eat, and that they didn’t die of waterborne pathogens was the hard part.

China, on the other hand, has built cities on a very large scale, without making sure people would want to come there. Now, the country finds itself in a very weird position, historically.

“[W]e should note that Rome wasn’t built in a day; neither are new cities in China,” the Baidu researchers wrote in their paper. “Constructing a new city is easy, while making it functional needs a long-term endeavor.”

Our next post examines how much urine splashes back on you when you use a urinal. To get notified when we post it → join our email list.

This post was written by Rosie Cima. You can follow her on Twitter here.