![]()

This week, the topic du jour on the Internet has been the saga of Martin Shkreli, the ex-hedge fund manager turned Big Pharma CEO who purchased the rights to the parasite-fighting drug Daraprim, then proceeded to boost its price from $13.50 to $750 per pill — an increase of more than 5,000%.

The move, which many have outed as morally questionable, is nothing new: for decades, drug companies have engaged in the practice of buying old, neglected drugs and “rebranding” them as costly specialty drugs. For Shkreli and his company, Turing Pharmaceuticals, procuring the 62-year-old Daraprim was nothing more than a routine business maneuver. Had Turing executives kept mum when the news broke, it is likely that the story’s lifespan would’ve been short lived. Unfortunately for them, Shkreli opened his mouth.

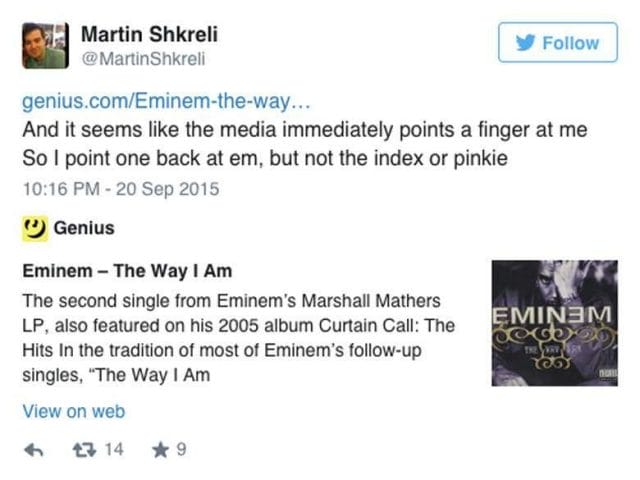

On live new segments, Shkreli defended his actions with a wry smirk on his face. On Twitter, he responded to the public’s concern by quoting rapper Eminem: “I point [a finger] back at you, but not the index or pinkie.” He called a reputable biotech journalist a “moron,” then, minutes later, took to reddit to defend himself. By this time, Shkreli’s arrogance had made him a cult villain on the Internet’s front page, and users did not react kindly. Wrote one user, “sanemaniac”:

“Here’s a question: are you fucking [dense]? All of your ethics aside, you need a lesson in how to handle a PR situation. Every time you open your mouth and allow some snarky comment to tumble out, you give people ammunition against you and fuel their hatred of you. How does a CEO of a multimillion dollar corporation get into Twitter slap fights? Are you 17? Honestly man. If you had said nothing, this would have been forgotten about in a day. Now you’ve immortalized your own stupidity on reddit and given people a reason to remember you. Fool.”

Shkreli’s handling of the Daraprim price inflation was, in every way, a case study of what not to do in the aftermath of a PR crisis. It has resulted in the Internet denouncing him as “America’s most hated man” and “the Big Pharma douchebag,” and has even drawn the ire of Donald Trump, who publicly derided him as a “spoiled brat.”

But just what should’ve he done?

For an answer, we turned to Levick Strategic Communications. As one of the the country’s leading crisis management PR firms, they’ve successfully navigated parties through major oil spills, airline crashes, and data breaches — often with little time to react. They’re experts in mitigating damage incurred by the press, and no one is more knowledgeable than the company’s CEO, Richard Levick.

Richard Levick lives and breathes PR. Over the phone, he talks quickly and pointedly about his firm’s 20 years of work, from salvaging the Catholic Church’s reputation, to helping a pet food company survive a massive recall. Crises can strike at any time, and he and his team have fielded their fair share of 2AM phone calls from panicked clients over the years.

When he first started out in the industry, the nature of the game was dramatically different. It was, in his words, a “republican” form of communications: CEOs knew the key journalists, financial analysts, and thought leaders who covered their beat — and they’d leak stories to the contacts who’d represent them the most favorably. With the rise of the Internet, this process changed dramatically.

“Companies today live in an age of peril: we are in a post-revolutionary state, which is highly democratic,” says Levick. “Matt Drudge, who helped break the Monica Lewinsky scandal, was a blogger working in his pajamas out of his basement, and he was ultimately responsible for impeaching the first U.S. President since Andrew Johnson.”

The Internet, adds Levick, has restructured the nature of PR: whereas firms once had time before news outlets published front page stories, the modern-day front pages are places like reddit and Twitter — and scandals can not only break instantaneously, but spread infinitely faster.

Almost immediately after the story made big waves on the Internet, Shkreli made appearances on national new stations, and took to Twitter and reddit — not to apologize, but to justify his actions.

Tweets from Shkreli immediately following the news that he’d raised the price of Daraprim by 5,000%

Shkreli’s fatal flaw was that he chose to get into jousting duels with online dissenters. His responses — many of which were condescending, or outright childish — only stoked the fire under his feet.

While every crisis presents its own set of unique challenges, there are three universal keys to handling one: action, transparency, and leadership. A perfect example of this, says Levick, is how American pharmaceutical giant Johnson & Johnson got through their “Tylenol crisis.”

In 1982, Johnson & Johnson’s Tylenol was the country’s most successful over-the-counter product, with nearly 100 million annual users. The drug was so immensely popular that it represented 37% of the entire painkiller market, and accounted for 33% of the company’s year-to-year profit growth. Then, a massive crisis erupted: for unknown reasons, “Tylenol Extra-Strength capsules were replaced with cyanide-laced capsules, re-sealed in the packages, and deposited on the shelves of at least a half-dozen pharmacies in the Chicago area.” Seven people were killed.

In the aftermath, the first thing that Johnson & Johnson chairman, James Burke, did was to immediately alert the public, through national media, of the issue at hand (transparency). Then, standing before his profit-driven board, he posed an unusual question: “How do we protect the people?” (leadership). Though only a small sampling of the drug had been affected, his response was to entirely cease the production and marketing of Tylenol, withdraw it from every shelf in America, and admonish customers not to buy it (action). A case study from the Department of Defense elaborates on the aftermath:

“By withdrawing all Tylenol, even though there was little chance of discovering more cyanide laced tablets, Johnson & Johnson showed that they were not willing to take a risk with the public’s safety, even if it cost the company millions of dollars. The end result was the public viewing Tylenol as the unfortunate victim of a malicious crime.”

“You need to go beyond compliance before regulators act; then you inoculate yourself from criticism, and position yourself as the good actor,” says Levick.

After this crisis, Johnson & Johnson stock rose for the next 120 quarters. Moreover, people saw Burke as someone who put people over profits — a man who understood that customers are more important than making money. “That was leadership,” adds Levick. “That was running to the crisis.”

Shkreli’s dilemma presents a markedly different case. His drugs were not laced with cyanide; rather, he precipitated his own crisis by engaging in a controversial practice (boosting prices on old drugs), then greatly exacerbated the problem by staunchly and immaturely defending his actions.

Only when the backlash reached a boiling point did he let down his guard and agree to lower the price of the drug. If he’d ceded at an earlier point in the “crisis,” he could’ve avoided the brunt of the bad press, says Levick.

Levick offers a “basic playbook” to get through situations like Shkreli’s:

“One: Assess how bad the situation is. What’s the history of you making decisions like that? Is this one an exception, or will you have a trail of similar instances that will come back to haunt you? If it’s completely out of character, pull it back and say you’re sorry. Be sincere, and do it right away.

Two: Determine who you have offended with your action. Get representatives of the offended class to come forward and forgive you. People listen with their eyes: if they see people they trust in their community coming to your defense, they will forgive you much more quickly.

Three: Content is king. The more content you have in your favor on the Internet, the more it will push down whatever the offense is.”

In Shkreli’s case, history is not on his side. The Internet is a trove of information that never forgets, and a brief search of the CEO’s name yields a past riddled with similar controversies: he was fired from Retrophin for his “immaturity” (and, more pressingly, for illegally misappropriating funds), criticized by his investors for beging brash on Twitter, and came under fire for attempting to influence the FDA “not to approve certain drugs made by companies whose stock he was shorting.”

Were it not for his outwardly defensive appearances this week, all of this could’ve remained relatively buried under a sea of Internet content. “His fatal mistake was his arrogance and snarkiness,” says Levick. “In a crisis, you’re judged by how you do in your worst moment. I would’ve admonished him to think before he spoke.” As one reddit user writes, “you can rob the world blind, but you need to keep your mouth shut while you do it.”

Ultimately though, Levick says Shkreli’s breed of crisis tends to be “short-lived, and rarely fatal.” If time has told us anything, it is that most people say their two cents, move on, then entirely forget about such matters in the span of a few weeks. And then, for the Shkrelis of the world, it’s back to business as usual.

![]()

For our next post, we investigate Donald Trump’s misadventures in professional football. To get notified when we post it → join our email list.

![]()

This post was written by Zachary Crockett. You can follow him on Twitter here.