“My first royalty check was $90 for an entire month of cartoons. That was a very disappointing day.”

~ Dan Piraro, creator of Bizarro

The comics section of most newspapers is a time machine.

In an era where breaking stories can be shared in real-time on the Internet, it’s odd to hold a paper that literally contains yesterday’s news — and comics are no exception: reprints of old Garfield, Peanuts, and Dennis the Menace strips fill the page. The world has moved on, but in the newspaper, Garfield still loves lasagna, Lucy is still pulling away the football, and Dennis is still menacing.

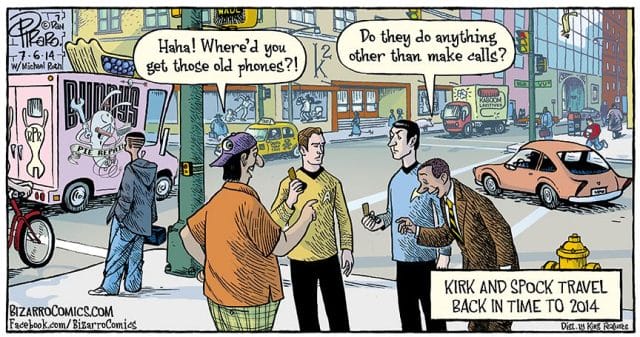

Nestled between these strips, Bizarro is a modern beacon of hilarity and social commentary. In a single panel, the oddball cartoon tackles issues like gay marriage, gun laws, and animal rights. It exposes, with reckless abandon, the frequent idiocy of mankind. Like its creator, Dan Piraro, it is both eccentric and doggedly political.

Piraro, like many cartoonists, began his career in an era where getting widely syndicated in newspapers was the only option to achieve a large readership. It was — and still is — an arduous process: he endured constant rejection, minimal pay, and, most formidably, the rise of the Internet and webcomics. After 30 years in the industry, he’s finally “made it.” Printed in some 350 newspapers across America, Bizarro is an award-winning strip with a cult following.

This is the story of how Dan Piraro created Bizarro.

An Artist In Oil Country

Via Bizarro, Dan Piraro

Raised by a petroleum engineer father in the late 1950s, Dan Piraro was “destined to live in redneck diesel states” as a child. At four, his family migrated from Kansas City to a small town outside of Tulsa, Oklahoma; here, the young misfit spent his formative years being “taunted by right-wing conservatives.”

Though he indulged in all of the usual ethers of boyhood — sports, ogling fast cars, and dressing up as an astronaut — Piraro found special refuge in a pencil and paper. By 5, he’d sketched his first quasi-cartoon: a gag involving two robbers showing up at a bank at the same time and arguing over who gets to steal the money.

Inching into adulthood, the teenaged Piraro, who by then had adopted a bohemian lifestyle, found little kinship in his peers. While his parents encouraged his talents, they weren’t purveyors of artistic expression. Of the “keep your hair short, don’t cuss in public variety,” they had artistic abilities of their own, but had never chosen to pursue them in any capacity.

“[My family] looked like your typical Walmart shoppers — and I wanted to be Salvador Dali, with this eccentric, crazy lifestyle,” says Piraro. “I wanted to be an artist so badly, but I was basically a naive, small town boob who had no idea where to start.”

Piraro (far right) in an early family photo

Piraro put his head down, diligently worked on his craft, and, in 1976, earned himself a four-year fine arts scholarship to Washington University in St. Louis. But he quickly became “utterly disillusioned:”

“It was all about non-representational art, and performance art. Anything recognizable got you a ‘C’; to get an ‘A’, you had to come up with some unrecognizable, conceptual bullshit — like a pile of broken glass — then write four paragraphs of bullshit justifying why it special.”

Just one semester into the program, Piraro dropped out, and found himself back in Tulsa. For several years, he toiled in a mire of “utterly meaningless jobs” — first as a counter clerk at a plumbing supply store, and later as a display artist at a large record store — all the while, struggling to understand his place in the world. Even his only modicum of creativity, a stint as the lead singer of a new wave band, aroused unwanted attention.

“We all had very short hair and pierced ears, during a time when everyone else in Oklahoma had a mullet,” he says. “Literally once a week, I’d get out of my car in front of the 7-11, and some guy in a pickup truck would drive by and shout, ‘Faggot!’ That sums up my early 20s.”

Seeking greener pastures, Piraro and his band emigrated to Dallas, Texas, where the plan was to “get big and famous.” Instead, Piraro found himself married within 6 months of arriving. Then, at 24, his wife unexpectedly got pregnant, and he was launched into premature fatherhood.

“I was scared to death I’d fuck it up,” he admits. “So I quit the band, and started trying to make a career where I could feed this screaming baby.”

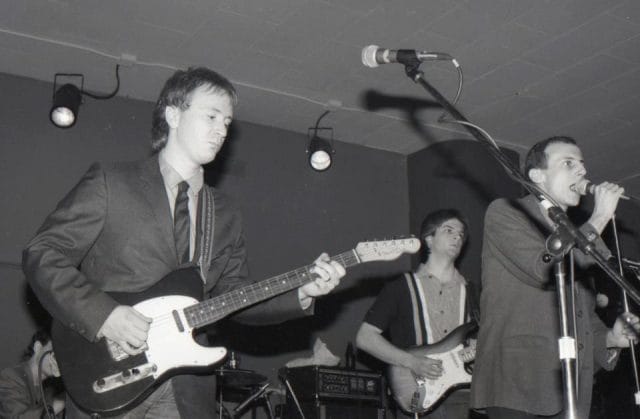

Piraro’s band, “The Doo,” performing in 1981

While working behind the counter of an art supply store, Piraro struck up a conversation with a man who happened to be a freelance illustrator for product catalogues; after showing the customer his high school portfolio, Piraro was offered an assistant position.

“I was able to do what he could do pretty quickly, and soon, I took over all of the drawings,” says Piraro. “It was decent money, but the work itself was mind numbingly tedious. There are only so many ways you can draw a bag of Cheetos.”

By 1981, he’d segued his experience into a job as a commercial artist for Neiman-Marcus. Along with a small team of “edgy art-school kids,” he spent long days sketching black and white renderings of products for mail-order catalogues. Piraro often found his mind wandering:

“To entertain myself, I would draw these odd, nonsensical cartoons of odd people doing strange things, with little narrations. They didn’t make much sense, but people liked them. I guess they had a certain kind of charm. My friends started collecting these little photocopied collections of my cartoons, and from time to time they would try to convince me to get them published. I would say, ‘Oh come on—people don’t publish this kind of stuff.”

In response, a colleague brought in a newspaper, and showed Piraro a strip of The Far Side, by up-and-coming comic artist, Gary Larson. Focusing on little, strange portraits of life and oddball characters, Piraro was instantly smitten. A few days later, Piraro fortuitously came across a People Magazine article on Cathy Guisewite, a young cartoonist whose strip, Cathy, had recently been syndicated by hundreds of newspapers across the country.

“The article made it sound so stupidly simple,” he recalls. “She just sent the strip to a big syndicate, and they instantly said, ‘We’d love to have you!’ I thought, hell, I can be a cartoonist too.”

The Syndication Blues

Via Bizarro, Dan Piraro

Long before xkcd and The Oatmeal, when newspapers offered the largest distribution channels, syndication was considered to be the apogee of success for a cartoonist.

The process, which is essentially the same today, works as follows: After accepting a cartoonist’s weekly strip from thousands of applicants, a syndicate embarks on a long, painstaking quest to sell it to newspapers. When a newspaper accepts a strip, it pays the syndicate a sum (between $5 and $50 per week) for the right to feature the cartoon. The syndicate keeps 50% of this money, and passes on the other 50% to the cartoonist. Essentially, the syndicate is a middle man between a cartoonist and newspapers.

Syndication is a numbers game: the more papers a strip is sold to, the more income it makes for the cartoonist and the syndicate. Signing on 50 small town newspapers won’t generate much income; signing on more than a few hundred papers can make an artist a comfortable salary.

After reading the story on Cathy Guisewite — whose strip was syndicated in some 1,400 papers across the world — a naive Piraro assumed that selling his strip would be both easy and lucrative. As is usually the case with assumptions, his fell far short of reality.

Since his work was in a similar vein as Larson’s, he figured his best shot would be to submit his work to the syndicate of The Far Side, Chronicle Features. He shot off some of his doodles, and was swiftly met with a form letter response: “These are interesting, but not really what we’re looking for.” A dozen similar rejection letters later, he bought a book on cartooning, more scrupulously studied the submission process, and tried again — this time, sending 25 samples with a self-addressed envelope.

Via Bizarro, Dan Piraro

Many months of unsuccessful attempts passed before Piraro elicited an “encouraging rejection” from Chronicle Features editor, Stuart Dobbs. “He told me that, while they were interested in me, they already had a similar strip [The Far Side],” recalls Piraro. “But he told me to stay in touch.”

Finally, after several failed efforts, the 25-year-old cartoonist was offered his big break:

“One day, [Dobbs] called me and said, ‘I have good news and bad news. The bad news is that Gary Larson is jumping to Universal Press Syndicate, and we had no idea he was even thinking about it. But the good news is that we’ve decided to pick up your strip because we now have room for it.’”

At first, Piraro thought he “his ship had come in.” Quickly, he learned that syndication was not for the hasty: selling to newspapers is a very gradual process that often takes years. A whole year into syndication, Piraro’s strip, Bizarro, was only featured in seven newspapers.

“My first royalty check was $90 for an entire month of cartoons,” he recalls. “That was a very disappointing day.”

Gradually, the distribution of Bizarro rose: five years in, it was in 60 publications — but most of these were small town rags that paid the syndicate $8-10 per week for rights. As a single-panel gag that doesn’t have any recurring characters, Piraro’s strip was harder to market. For the first decade of his career as a syndicated cartoonist, he had to maintain his day job as a product illustrator.

Piraro (second from the left) with a bunch of cartoonist buddies in the late 90s

“I would work 5 days a week at commercial art studio, come home, have dinner, hang out with kids for an hour or so, put them to bed, then start working on my cartoon for the next day,” he says. “I’d basically signed up for 2 full-time jobs for 12 years without knowing it.”

At the same time, Piraro endured a messy divorce, and had to go through the abysmal process of coming up with jokes while battling depression. “It was hellacious, absolutely hellacious,” he says. “I was sitting there crying and trying to write a gag because I was behind my deadline. I cursed my career choice.”

In 1995, Piraro left Chronicle Features for the much larger Universal Press Syndicate; again, in 2002, he switched over to King Syndicate, which more than doubled his distribution from 150 papers to 350. Today, he enjoys a fruitful partnership with them — even in the era of Internet-based cartoons.

An Old-School Cartoonist in the Age of the Internet

Via Bizarro, Dan Piraro

The first online comic strip, Eric Millikin’s Witches and Stitches, appeared on Compuserve portals in 1985. Throughout the late 80s and early 90s, a slew of others followed suit. It wasn’t really until the latter 90s, with the rise of Google and banner ads, that “webcomics” really began to flourish. By this time, many traditional cartoonists had also begun utilizing the computer in the creation process.

In 1995, Piraro was taught how to use Adobe Photoshop by a designer friend, and it revolutionized his coloring process for Sunday strips:

“When I first started, you’d send your original art to the syndicate, and they’d give you a CMYK chart — a giant poster with hundreds of little squares of color. You’d specify where you wanted the color to go, plus the number of the color (for instance, ‘shirt, color #532’), and they’d do it for you. You’d see the final product in the newspaper a few days later, and you’d either go, ‘Oh, that worked out,’ or, ‘Ah, shit!’ Photoshop instantly simplified that process, and gave me more creative control.”

To Piraro, computers “were like Algebra:” complex, non-sensical, and hard to wrap his brain around. But unlike other “old guys” in the industry who were resistant to change, Piraro seized the opportunity to learn new technologies. Around 2000, he ditched the traditional process of snail-mailing his final cartoons to the syndicate in favor of uploading them to an FTP (FIle Transfer Protocol) network online. He also, for the first time, launched a blog on which he features his week-old cartoons.

Perhaps the biggest payoff the Internet offers, says Piraro, is that is serves as an “arena of free speech” — a welcome refuge from the “puritanical” confines of the syndicate. His cartoons, which frequently dabble in the liberal politics of vegetarianism, gay rights, and animal cruelty, have often run him into trouble with clients.

Via Bizarro, Dan Piraro

“I once lost a small paper in Texas over a Karl Rove joke,” he laughs. “Nobody would’ve blinked twice at a joke like that on the Internet.”

While the Internet has helped Piraro, it has also threatened his trade.

The new model for aspiring online comic artists is in direct opposition to that of syndicates: Put really good content out there for free. Build a following. Monetize with ads and merchandise. Traditionalist cartoonists argue that this plethora of freely available content is partly contributing to the stagnation of print comics.

Matthew Inman, creator of the immensely popular online strip, The Oatmeal, justifies giving away his work for free with web traffic: “It’s my way of building an audience who like and support me,” he’s said, “and who will, in turn, buy stuff from me.” So far, this strategy has worked well for him: with millions of monthly visitors, best-selling books, and an ardent social media following, Inman likely makes a seven-figure salary — 80% of which comes from merchandise, and 20% from ad revenue.

While webcomic artists like Inman succeed in cutting out the middleman (the syndicate), it comes at the expense of doing all of the promotional work on their own. Increasingly, cartoonists are becoming hustlers, salespeople, and entrepreneurs — none of which Piraro aspires to be. Still, the Bizarro creator speaks of Inman with a tinge of envy: while he lists some 9,000 original cartoons, paintings, and sketches on his webpage, his sales are unimpressive.

“I’ve been around for 30 years,” he says. “Over that time, I’ve accumulated more fans than him, but I don’t have that traffic on my site. He knows how to play the social media game, and I just don’t have that clout.”

Contrarily, Piraro has maintained his clout through raw talent: while other print cartoonists have watched their syndications crumble in an era of shrinking newspapers, his list of clients has continued to incrementally grow.

A Painter at Heart

“FOX News Special Report” (2004, Watercolor); Dan Piraro

After 30 years as a cartoonist, Dan Piraro has, admittedly, grown weary.

“There are no breaks at all — it’s unrelenting,” he says. “It’s been constant work, constant gags, and very little time off.”

This is life for a syndicated artist on a daily deadline. In three decades, he’s only been on vacation a handful of times; even then, he had to stock up a week’s worth of ideas in advance to make it work, and spent the whole time away from his desk worrying about which jokes he’d use upon his return. The expectations of the syndicate, along with the level of creative output, are incredibly demanding.

For these reasons, Piraro says his days as a cartoonist are limited: within a few years’ time, he’d like to return to his roots as an oil painter. He also wouldn’t mind traveling to Italy with his “muse” and partner, who he affectionally calls “Olive Oyl.”

But for now, the man behind Bizarro is dead-set on his craft.

“Every now and then, I’ll write a joke and think, ‘Oh God, that’s good,’” he admits. “That’s going to make people laugh.

This post was written by Zachary Crockett. You can follow him on Twitter here.

To get occasional notifications when we write blog posts, please sign up for our email list.