![]()

Every March, Richard Whelan boards the Shepherd II — one of hundreds of hunting vessels in Newfoundland, Canada — and drifts into the frigid eastern waters to hunt for seals. For two months, he lives aboard the battered ship, subsisting on minimal rations and braving blisteringly cold temperatures.

When Whelan spots a seal scooting across the ice, he takes out his .22 Magnum, zeroes in from a distance, and fires. In the ensuing moments, he docks the boat, chases the animal down and bashes in its skull with a taloned wooden club — a practice known as “seal clubbing.” After ensuring the seal is dead, Whelan swiftly peels off its fur with a 12-inch knife; often, the majority of the animal’s body is left behind on the blood-stained ice. Though channels exist for seal meat and oil, the animal’s fur, which is processed, tanned, and fashioned into $4,000 luxury coats, is the sealer’s crown jewel.

Despite the attention it receives, the seal industry is quite small today, though this wasn’t always the case. During its golden age, sealing was the second largest source of revenue in Newfoundland’s isolated economy; by last year, it accounted for less than one-tenth of 1%. Led by animal rights groups and celebrity supporters, decades long anti-seal clubbing campaigns have severely crippled the trade. Seal products are now banned in nearly every market — the U.S., Japan, and the majority of Europe included — and strict regulations and quotas have been instituted by the Canadian government.

But seals are not one of the world’s 20,000 endangered species, nor are they scarce in Canada. For most seal hunters, the dying hunting industry, worth only around $1.5 million in annual sales, is only a part-time job and provides little financial security.

Why did the world organize itself to effectively end the practice of seal clubbing — especially when there exists a plethora of threatened species that are slaughtered on larger scales? And while “clubbing” a seal with a mallet out in the wild sounds terrible, is that worse than killing an animal that lives the entirety of its life in a processing plant?

Could it be that we saved seals simply because they’re cute?

The Birth of the Sealing Trade

Sealing has a rich, complex history. Though practiced in multiple cultures (Namibia, Greenland, Norway, Russia, Iceland), over 97% of seal hunting has historically occurred in Newfoundland and Labrador, on the eastern coast of Canada.

For Inuits and native peoples of Newfoundland, seal hunting dates back more than 4,000 years. In the harsh, icy territories, these animals provided a means of sustenance: meat — rich in fat, protein, and vitamins A and C — provided necessary nutrients; fur pelts were fashioned into coats, boots, and blankets. When a young Inuit boy killed his first seal, it would be cause for celebration: a huge feast would be held, and every part of the animal would be utilized.

By the early 16th century, an influx of Portuguese, French, British, and Basque settlers had established a commercial sealing industry. These men — most of whom were fishermen — would organize multi-month expeditions to earn extra income in the cod offseason. A significant seal market soon emerged in Europe, where the fur was valued for its warmth and oils were championed as a healing agent; by 1773, 128,000 seals were being harvested each year.

Sealing continued to grow, and in the 19th century, the trade saw its Golden Age. Foreign investors stepped in and the hunt greatly expanded, employing shipbuilders, carpenters, and refiners, who extracted oil from seal blubber and sold it as a dietary supplement. Between 1800 and 1900, over 33 million seals were harvested. Sealing became inextricably weaved into Newfoundland’s economy, and trailed only cod fishing as the province’s biggest revenue stream, pulling in $1.5 million per year ($28 million in 2014 dollars).

Large steam-powered vessels were introduced in the early 20th century, allowing for bigger hunts over wider territories, but not without risk: the ships were prone to accident, and in a 50 year span, 400 ships were lost and nearly 1,000 men perished. In one instance — The Great Newfoundland Sealing Disaster of 1914 — 78 sealers perished and another 173 were lost at sea, never to be found. Ships were controlled by wealthy investors, and employment conditions for sealers soon deteriorated: they were underfed (eating only biscuits and tea for days at a time), given little in the way of warm clothing and safety gear, and were allocated little time for sleep or rest.

During World War II, most sealing vessels were enlisted for use in the service, and the industry came to a standstill; in the 1960s, it emerged with a vengeance, fueled by an incredible demand for newly-in-vogue fur. With machinery, increased labor forces, and more scalable methods of production in place, annual seal kills rocketed to over 300,000 per year; for the first time in its history, the trade began to attract a pushback.

Years of regulation, lobbying, and anti-sealing campaigning ensued, and at the heart of the debate were the “seal clubbers” themselves.

The Life of a Modern-Day Sealer

For seal hunters registered in Canada, life isn’t grand. The average harvester earns only 20-35% of his yearly income — a meager $5,000 to 8,000 — from sealing, and relies on other work to survive. A vast majority of sealers come from Canada’s poorest, most isolated regions and have few alternatives for work.

For many years, William Case, a night watchman by trade, participated in the seal hunt to earn extra income. In an interview with the Canadian Geographical Society, he elucidates a lifestyle that is both incredibly difficult and non-lucrative. Docking a schooner in early March, he’d be at sea for two months with limited supplies, often facing great dangers and harsh terrain.

One time, sailing out in remote waters, Case’s vessel came across a small rowboat that had drifted out to sea; inside were two men: one dead, and the other “with his arms frozen to his oars, and clinging to life.” The life of a sealer, reminds Case, “ain’t for the faint of heart.” Undoubtedly, sealers face some of the harshest weather conditions in North America, braving the frigid eastern waters of Newfoundland. Leo Seymour, an ex-sealer, says that on a “rough year” like 2014, ice conditions can be nightmarish:

“It’s wicked. It’s wicked. Bad days. Blowing gales and then the fog and everything. And the ice is so heavy. I s’pose some fellers takes a chance on it. Some fellers might have 1,500 or a couple of thousand seals so it’s not so bad. But if you’re only getting a couple of hundred seals it’s not even worth fueling up your boat for. You can’t even pay your expense.”

But sealing has harsher realities than the weather: animals must be clubbed to death. Case, whose ship would haul in “between 300 and 1,500 seals,” recalls the “rather crude” method used to get the job done:

“When we could reach them on the ice cakes, a blow on the snout with a club would do the trick. We shot them in open water and fished them out with gaffs. Sometimes, you’d shoot one from a distance and trek about a mile or two. We went in small boats, two men in each one, the gunner and the other his mate. We skinned the seals on the ice.

A rip with the knife and in a jiffy the pelt would be taken off and the carcass left for the birds. Sometimes, the old hoods [seals] would make at us, but we could dodge them, as they always moved along in a straight line, and then the club or the gun would soon fix them.”

The skins (or pelts) are the means of financial subsistence for the hunters: while minimal markets exist for oil and meat, seal fur is the driving force of the industry, constituting about 90% of the market. As such, sealers take great care to preserve them. Any knife knick or bullet hole in the pelt can result in price deductions when it comes time to sell them to processing plants and direct-contact kills are encouraged.

To slaughter a seal, a hunter uses a hakapik, a heavy wooden club with a hammer head (used to crush the seal’s skull) and a hook (used to drag away the carcass post-kill). The tool, a Norwegian innovation, is favored by sealers for its ability to make a supposedly “humane” kill without damaging the pelt.

Top: A seal hunter stands over his kill; bottom: seal pelts are offloaded in Newfoundland. Via Frank Kuin; more images of the seal hunt can be found on his Flickr, and his website, frankkuin.com

Fergus Foley, who participated in the seal hunt for ten years to support his fishing income, says it can get a lot worse than clubbing a lone seal. Sometimes, pups, or baby seals, are lost in the process — something Foley’s now immune to. In an interview with Canada’s Department of Fisheries and Oceans, he clarifies some of the gruesome realities of his trade:

“The best day we done, we took approximately one hundred and eighty seals. I seen a female being pelted and the pup came out of her when they cut her open, the pup was dead. Someone passed the comment, ‘If Greenpeace were only here to see this!’ There were a few occasions when we took the female Hood seals and left the pup on the ice. On two occasions, I observed pups falling out of the female while being pelted on deck. The two pups I observed were alive and were thrown over the side. I seen these pups crawl up on the ice after we threw them over aboard.”

The Canadian Sealers’ Association (the governing body that represents all of Canada’s commercial seal hunters) maintains a strict set of “kill guidelines” that sealers must follow — both to ensure that fishery regulations are followed and to maximize profits from seal furs. In a “how-to” video intended for sealers, these methods are demonstrated. “The harvest must be based on sound science,” the film warns, “humane killing is the key to success!”

According to the CSA’s President, Frank Pinhorn, the humane way to go about killing a seal is a three step process: “stun the seal with a swift knock to the head, check to ensure the skull is crushed, and cut him open to bleed out.” Quality, reminds Pinhorn, is key here. A sealer must take great care not to “knick organs” during the skinning process, lest the skin, blubber, and meat be contaminated with byproducts (“bacteria spread from the gut can cost thousands of dollars”).

The Seal Market: Making an $8,000 Coat

After furs are stripped from a seal, hunters return to the port and sell them “in raw form” to processing plants; blubber is removed and they are appropriately conditioned for use in clothing. These plants maintain a complex pricing system which encourages as little tampering with fur as possible and as much as $2 is deducted from each pelt for “knife knicks,” yellowing (caused by excessive bleeding), and tears. The proper killing of a seal doesn’t just benefit hunters, says Pinhorn — it “maximizes the financial benefit of all stakeholders involved in the industry.”

But in reality, the payoff for hunters is minimal. Today, depending on quality, pelts go for $20-35 each; after the ship captain takes his cut, that amounts to a little over $15 for the hunter that clubbed the animal. Pelts are not particularly lucrative until the retail stage, and the process to get to that point is painstaking.

When processing plants purchase skins from sealing vessels, they come in crude form (bloody, and with blubber still attached). At the plant, the skins are soaked in brine for several weeks, then go through a tanning procedure; if a skin is excessively yellow or sun-spotted, it is typically dyed a dark color. From the plant, the pelts are sold to brokers, essentially middlemen with retail connections who sell them at a markup to clothing and accessory manufacturers. Once the goods are crafted, they are then disseminated to seal outerwear shops and sold for exorbitant prices.

A seal skin being prepped for the fashion world

Halloran’s workshop, where $8,000 seal fur coats are crafted

Bernie Halloran operates Always in Vogue, one of several seal clothing stores in Newfoundland. After purchasing his skins directly from Carino (Canada’s largest sealing plant), he acts as his own manufacturer in addition to retailing. Since Halloran is a long-time, local trader, he “receives special deals” on his wholesale fur purchases.

In Canada and other particularly frigid countries, seal fur doesn’t just provide warmth — it serves as a status symbol. Halloran’s shop carries an array of items: jackets, hats, bags, boots, and bow ties, and admits that his items (and seal products in general) are “classified as luxurious.” A full-length seal coat parka made from “anthracite-colored top-tier fur” runs about $5,000 to $8,000; on the lower end, spotted seal throw pillows go for $150 a pop. When he first opened shop 30 years ago, Halloran tells us he enjoyed great business — until product bans and sealing backlash stampeded his success:

“It is sad that the world markets have been slowly closing — Europe, USA, Russia. Seal is a bullied industry. What hypocrites! My thinking is right and I know it to be right…if killing seals is wrong, then the world is wrong. It’s simple: if people don’t like the product, don’t buy it. I don’t smoke but I don’t condemn people who do.”

However, Halloran’s business has been good to him: in the past, on a good year, he’d purchase 1,000 to 1,500 pelts for manufacturing; this year, he bought 3,000, and next year he forecasts a need for 5,000. He attributes this entirely to an emerging demand for seal products in China:

“China has been a beacon of hope — they are just falling in love with seal products. I see this first hand every time I visit (I just returned last week). It is my mission to help save this industry and show it for what it truly is: the items we are producing now are amazing — fashion plus — and the Chinese are starting to see the same. It’s about to explode; I know it and see it every visit.”

But China isn’t the honeypot Halloran makes it out to be. While certain niche demands exist in Asia (seal penises are often purchased for fertility purposes, for instance), deals to distribute seal meat and oil on a larger scale have fallen through in recent years. Several Canadian politicians have declared that seal furs are “on their last legs,” and that any gains retailers may be experiencing now will be short-lived.

Halloran’s success is atypical in a market that for decades has been in a sharp decline.

A Dying Industry

Sealing was once a lucrative, burgeoning industry; today, it is on its way out.

Ten years ago, sealing was an industry with $34 million in annual sales; last year, that number was $1.5 million — $400,000 of which was overhead for sealers (boats, permits, guns, etc.). Though thousands of hunters are registered to hunt, only 390 actually participated, down from 6,000 a decade ago. In the past year, the number of sealing vessels has also decreased from 540 to 98.

With the implementation of the Seal Protection Regulations in 1965, the Canadian government established the first ever set of limitations on the industry: set hunt dates, strict controls on killing methods, and the requirement of sealers and ship owners to be licensed. Six years later, in 1971, the first “kill quota” was set at 150,000 seals — an effort to monitor the industry. Over the years, the quota, or “total allowable catch,” has gradually increased. By the end of the 1970s, it was set at 180,000; by 1990, it was 250,000; by the mid-2000s, it peaked at 350,000 seals.

To an outside observer, it would appear the industry has experienced growth and is demanding higher allowances, but this simply isn’t true. While the quotas have increased, the “total catch” (actual number of seals killed) has dropped dramatically. In 2008, for example, 217,000 of 275,000 allowable seals were killed (79%); by 2013, only 17% of the quota was reached.

Canada’s Department of Fisheries and Oceans cites an array of reasons for the decline in annual catch, from a strong Canadian dollar dampening export values to excessive ice cover, but the true source of the industry’s decline can more likely be attributed to the decades-long anti-sealing battle staged by animal rights groups.

The Anti-Sealing Backlash

A troupe of seal hunt protestors are arrested in Canada

As early as the 1950s, animal rights groups surveyed Newfoundland seal fisheries and expressed concerns over the moral turpitude of the killing methods. But it wasn’t until the mid-60s, when the northwest-Atlantic seal population declined by 50 percent, that activists launched into a full-fledged attack campaign.

Broadcast by the CBC in March of 1964, Les Phoques de la Banquise, or “The Great Seals of the Ice,” chronicled the exploits of Canadian seal hunters; a scene showing a sealer skinning an animal alive and leaving it to wriggle on the ice sparked international outrage (the hunter later admitted he was paid by producers to commit the act, but the incident nevertheless catalyzed the anti-sealing movement). On the sole platform of “ending the commercial exploitation of seals,” The International Fund for Animal Welfare (IFAW) established itself in 1969. The organization even hired Coca-Cola’s advertising firm to launch a “Stop the Seal Hunt Campaign,” which was wildly successful in boosting donations.

Protesters’ efforts paid off. With the signing of 1972’s Marine Mammal Protection Act, all seal products were banned in the United States (though it was a small market to begin with). In 1983, the European Union, responsible for importing 75% of Canadian seal pelts, implemented a permanent ban on “whitecoat” baby seal products. To add more misery for Canadian sealers, Safeway stores across Britain discontinued all Canadian fish products in protest. The ban tore apart the sealing community.

A major issue was the killing of “whitecoat” seals. From birth to two weeks old, harp seals have fluffy, white fur (this turns gray, brown, or spotted after two weeks). Traditionally, the majority of seals killed by hunters were baby whitecoats. Animal rights groups saw this practice as unsustainable and inhumane, and launched a campaign that would appeal to the masses: incredibly cute, big-eyed baby seals were juxtaposed with blood, guts, and murder. The Canadian government responded to the uproar by banning the hunting of whitecoats in 1987.

In recent years, continued efforts by the IFAW, PETA, and The Humane Society have resulted in much more serious implications for sealers. Mexico banned all seal product imports in 2006; the European Union, which had previously banned only whitecoat imports, outlawed every seal import, regardless of age — a move that struck a permanent blow to the seal market. The Russian Federation, Taiwan, and others have since followed suit.

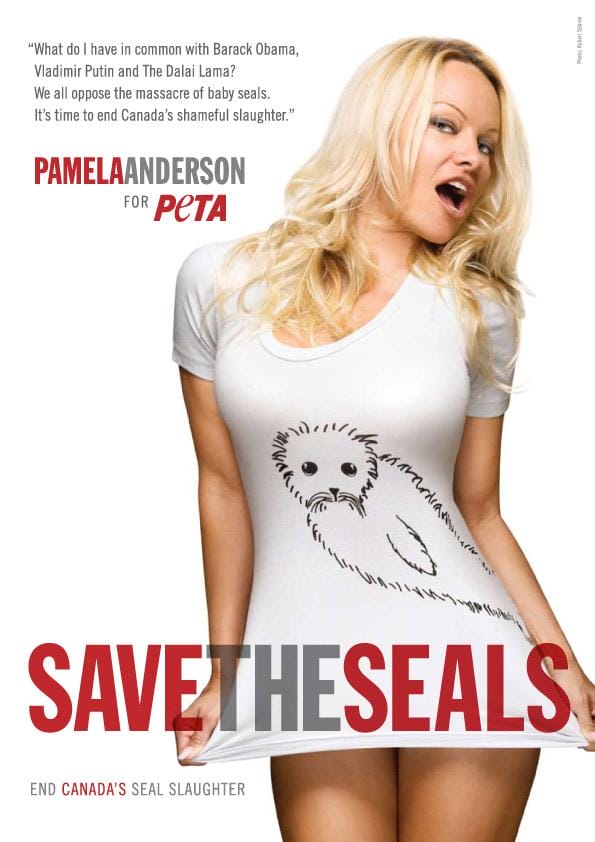

While the industry is nearly dead today, it still receives a tremendous amount of attention and coverage; PETA recently launched a celebrity seal campaign featuring the likes of Pamela Anderson and Perez Hilton, and lists the cause as its “top priority.”

Inuits and Cultural Exemption

It is important to distinguish that most of the backlash against sealers is aimed at the commercialization of the trade; Inuits — the natives of Newfoundland who have subsisted on seals for hundreds of years — are nearly exempt from regulation. Though they only represent 3% of the seal trade, they have a separate hunt each year which is much less controlled.

For Inuit hunters, sealing isn’t just a source of income — it’s a way of life, and a keystone of their culture: the seal is their mainstay. Inuktitut vocabulary includes specific terms for “seal bone” and “seal fat,” and legends are perpetuated within the culture of kinships and relationships with seals. In his 1991 study, “Animal Rights, Human Rights”, anthropologist George Wenzel spent two decades with Inuit sealers, and writes of “the impact of the animal rights movement upon the culture and economy of the Canadian Inuit.” In his text, he argues that animal rights groups, while “well-meaning people,” were full of misunderstanding and ignorance that “inflicted destruction on the vulnerable Inuit minority.”

Due to such studies, Inuits have historically been given more leeway in international sealing bans (Europe included a clause in their 2006 seal product ban that allowed for Inuit natives to continue exporting in small numbers, for instance). But anti-sealing campaigns have purportedly had a negative impact on this community as well.

Paul Irngaut, a wildlife communications advisor with Nunavut Tunngavik, speaks to the effects that a 1980s demonstration had on his village:

“In a small community like Resolute, income from sealing dropped from $54,000 in 1982 to $1,000 in 1983. Today, we still struggle. The income gained from seal hunts enables hunters to be able to feed and support their families, as well as other families…There once was a market for such goods, which would also support families and their ability to afford goods needed for hunting, and food to put on their table. Remember: Nunavut is a place where a cabbage can cost $28!”

As Canada’s National Inuit leader, Terry Audla represents 60,000 Inuits across the country. He says that the Inuit culture’s traditional lifestyle requires the consumption of “free-roaming, nutrient-dense animals.” Sealing, he argues, keeps his community alive. In a manifesto published online, Audla adds that “Inuits rely on the seal hunt for its shared market dynamics and the opportunity to sell seal pelts at fair market value,” and that activists have “negatively impacted [sealers], along with other remote, coastal communities who have few other economic opportunities.”

In April of 2014, talk show host Ellen Degeneres proclaimed her support for the Humane Society and its aim to end seal hunting; in response, Inuits took to Twitter to defend their “right.” A sea of “Sealfies” emerged: Inuits and Canadian supporters alike posted photos of themselves clad in seal boots and jackets, and even sprawled half-naked across seal rugs. The campaign garnered national attention.

One 17-year-old Inuit, Killaq Enuaraq-Strauss, took to YouTube to express her disappointment with her favorite television personality:

“You’re an inspiration as a woman but also as a human being, but let me educate you a bit on seal hunting in the Canadian arctic. We do not hunt seals … for fashion. We hunt to survive. I own sealskin boots and they are super cute, and I am proud to say that I own them, and I also eat seal meat more times than I can count. But I can’t apologize for that.”

The Humane Society was quick to clarify that it didn’t oppose the Inuit hunt — only the commercial hunt; PETA operates with the same ideology. The organization’s spokeswoman, Danielle Katz, tells us that her organization is primarily interested in the commercial hunt, which accounts for “97% of the seals that are killed,” and says the “Inuit sealers are under no threat” in the seal market.

In the grand scheme of the industry, sealing isn’t lucrative for anyone: sealers struggle to get by, the government wastes time and resources on a dying trade, and groups like PETA and the Humane Society have spent millions combatting one of the world’s smallest commercial fur markets.

The Cute Bias

While those involved in the seal trade maintain that it’s humane, sustainable, and well-regulated, animal rights activists and protesters call the practice cold-blooded and barbaric. One question lingers: why so much undying support for protecting seals in particular?

There is a compelling case to be made that sealing is particularly demonized due to the fact that the animals are cute and fuzzy, a fact animal rights groups have consistently relied on for campaigns. The imagery used by PETA, The Humane Society, and other activist groups is striking and consistent: big mammalian eyes, fuzzy snow-colored fur, blood against white ice — cuteness (juxtaposed with violence) has been employed to garner public interest, and it has worked.

Harp Seals, an activist group working to end the Canadian seal slaughter, conjures such language to mobilize people to join their cause. Seal pups are “famous for their big black eyes and fluffy white fur,” they write, “and are astounding in their innocence, individuality, gentle nature, and beauty.” The language appeals to society’s predisposition for pedomorphism, or things that resemble human babies (big eyes, fuzzy little heads, etc.); social psychologists have long argued that these traits are what make cute creatures endearing.

Regardless of cuteness, the harp seal population in Canada is currently estimated at 5.6 million — nearly triple what it was in the 1970s — and with nearly 20,000 species threatened by extinction, the populous animal seems a strange target for so much attention. Renowned ecologist Jacques Cousteau addresses this:

“The harp seal question is entirely emotional. We have to be logical. We have to aim our activity first to the endangered species. Those who are moved by the plight of the harp seal could also be moved by the plight of the pig…We have to be logical. If we are sentimental about harp seals, which are not endangered because they are partially protected, then we have to also be emotional about pigs.”

Dr. M. Sanjayan, a noted conservationist, believes that non-profits and animal protection agencies have a deeply flawed selection methodology rooted almost solely in “preserving cute and fuzzy animals” rather than the creatures that “actually keep our planet humming.” He touches on this in an interview with National Geographic:

“What we decide to save really is very arbitrary—it’s much more often done for emotional or psychological or national reasons than would ever be made with a model…people end up saving what they want to save—it’s as simple as that.”

Sanjayan cites ants as a prime example of how activists are biased toward cuteness over ecological function. The tiny creatures are essential environmental helpers — they disseminate seeds, aerate soils, and eliminate human pests — but are not represented by animal rights groups. “If we’re going to save pandas, for instance, rather than ants,” adds Marc Bekoff, an ethologist at the University of Colorado Boulder, “we need a good reason, and being cute is not a good reason.”

In Western society, cows are on the opposite spectrum of the cute bias. Every year in the United States, 40 million cattle are slaughtered; their skin, manufactured into leather, accounts for 50% of their total byproduct value. We’re the world’s largest producer of hides, with an annual supply of 1.1 million tons. Most commercial cattle endure horrendous living conditions: they’re crowded into factory farms with inadequate food and water, pumped full of antibiotics, and spend their entire lives milling around on concrete floors without the “luxury” of living in their natural habitats.

Cows are killed by a swift blow to the skull with a stun gun, and a slit to the throat; they are then hooked to a chain by their hind leg, and bled out over a tub — often still alive, but not coherent. Under the U.S.’s 1958 Humane Slaughter Act, this is not only legal, but considered a “compassionate” way to die. Chickens endure even worse: they are hung upside down, shocked into paralysis, then drowned in hot water. The act of seal clubbing, when gauged with these methods, seems somewhat tamer, but has been sensationalized as unapologetically violent due to the fact that seals are more aesthetically pleasing than cows and chickens.

Whales present a case that isn’t entirely dissimilar. Beneath hotly-contested Canadian ice, the giant, unattractive creatures go unloved. Recently, the Canadian government moved to take humpback whales off the threatened species list; instead, the animals will be labeled a “species of special concern” — a title that comes with limited protective privileges. This change of classification means “the humpback’s habitat will no longer be protected under Canada’s Species at Risk Act, thereby removing some of the risk of legal battles with environmental groups.”

Yet above ice, seals continue to be a success story. They’ve been haloed by legislation, defended by celebrities, and largely protected from the force of whooshing clubs. It seems that, at least in this case, cuteness ensures conservation.

Our next post takes a look at which dog breeds get adopted most often and which ones don’t. To get notified when we post it → join our email list.

![]()

This post was written by Zachary Crockett. You can follow him on Twitter here.