“It’s closer to the wild west up there.”

~ Astrobotics CEO John Thornton.

![]()

In November 2015 near the beaches of Hawaii, the latest incarnation of a military rocket dating back to the early 1960s called the Super Strypi launched its inaugural voyage. At first operations appeared normal. The rocket lifted off, departed the white sands, began spinning, which stabilizes the craft, and seemed destined for a planned orbit about 260 miles above the planet.

But about a minute after takeoff something went wrong –– the Defense Department doesn’t share specifics –– and the Super Strypi came crashing back to Earth, splashing down in the Pacific. Failed rocket launches aren’t noteworthy by themselves. But this vessel had a curious payload: human remains, packed into metal cubes.

The hope was for the rocket to drop the space urn into orbit, so families could peer up at loved ones in the night sky, a funeral rite of the future. Today the bereaved can pay to have remains sent here, to the moon or even to(wards) a galaxy far far away.

Companies like Elon Musk’s SpaceX, Richard Branson’s Virgin Galactic and Jeff Bezos’s Blue Origin make headlines with promises of accessible, commercial space flight that will open up amateur space experimentation, new communication systems and travel to Mars. Now anyone can monitor a satellite’s progress from a laptop. But the new space age is also opening niche space-borne products to the average person, like space-aged scotch and, yes, space funerals.

Some space-y remains, such as psychedelics evangelist Tim Leary and Star Trek creator Gene Roddenberry, have been sent up already. But traditional funeral prices have increased to the point that a space funeral is in a competitive ballpark. We took a look at what it takes to catalyze a loved one’s return to starstuff, the interwoven supply chain of doing so, and the guiding trends.

“It’s a challenge marrying two of the most conservative industries on the planet,” says Charles Chafer who runs space burial firm Celestis. “Aerospace and funeral.”

Spin Long And Prosper

Spock’s funeral

While the thought of firing a loved one’s remains into space may seem excessive, the idea isn’t without precedent. Cultures throughout history tend to “see off” their dead in one way or another, whether through days of prayer or pushing corpse-filled burning boats to sea like the vikings. Space has always been hallowed ground, akin to heaven, where humans imagined lost souls, the dead, heroes or gods, out there wandering among the cosmos.

Today getting remains to space is a little less mystical.

First there is the space burial service, like Celestis or Elysium, which takes payment from the departed family, receives the ashes and provides the container. The ashes are pretty benign and, as far as electrical, thermal or communication requirements, have none, according to Celestis’s Chafer. They’re ashes. But the capsules must be secure, passing thermal, vibration and vacuum tests so they won’t explode. Chafer says the canister is technically a spacecraft.

CubeSats do offer a DIY path to build a container for a loved one, but Chafer doesn’t worry that it will hamper future business.

“You could also bury yourself,” he says.

The space urn then needs a ride. Burial services go to companies that operate larger crafts destined for Earth’s orbit asking for a lift, filling space on their crafts. In August Elysium announced a contract with Astrobotic Technology, a Google Lunar Xprize participant, that builds lunar landers and rents out payload space for companies and research organizations that want to send equipment to the moon — though they have not launched a commercial voyage yet.

CEO John Thornton says someday his company will be “the UPS of getting to the moon.”

Finally, both urn and vessel need a big engine to escape Earth’s gravity. That’s where military launches like the failed Super Strypi or commercial big boys like SpaceX come in, launching rockets with satellites, scientific equipment, climate instrumentation and other payloads, towards their destination. Companies bid to get space on the flights years or more in advance. There’s only so much room on the crafts. So, to be clear, there are no dedicated space burial flights. The remains find room on crafts already on their way up. All that fuel isn’t burned for a funeral.

But after the ashes secure a spot, “Then you sit back and wait for them to fly,” Chafer said.

Of course rocket launches are still far from sure things. What happens if a rocket fails or never launches, and the ashes don’t make it? Elysium, which had payload on the failed Super Strypi rocket, never answered our inquiries — though obviously the unsuccessful burial wasn’t their fault other than picking the unlucky launch provider. But Celestis’s Chafer says they’ll let the remains (if the family still has leftovers) fly again for free but sometimes people are happy enough with the new spectacular ending for mom or dad.

See The Light

Alan Ginsberg, Timothy Leary and John Lilly

When Timothy Leary was nearing the end of his life he saw a video presenting the idea of being buried in space and Chafer says the godfather of LSD stood, pointed and said something close to, “That’s me. I’m going to join the light.” And he did. In April of 1997 on Spain’s Canary Islands Leary’s remains, Roddenberry’s and 22 others’ drew worldwide headlines as they boarded Celestis’s first private memorial spaceflight and fired off into the sky.

As the New York Times noted at the time:

The official purpose of the rocket, launched from a Lockheed L-1011 airplane, was to put Spain’s first satellite into space. But bolted to the rocket’s third-stage motor was a canister containing the ashes of the 24 people in aluminum capsules, each one engraved with the person’s name and a commemorative phrase.

”They look like little cocaine vials, which is kind of hysterical in Timothy’s case,” [Leary’s friend Carol] Rosin said.

Their ashes would fly 350 miles above the earth, completing 15 revolutions each day, before burning up in the atmosphere five years later in May of 2002.

Some Celestis flights don’t get far enough from the planet to burn up on re-entry. They fall back to Earth, are retrieved and the family can say that mom finally made it to space. But for Celestis’s orbit funeral (which costs about four times as much) the plan is to eventually burn up the space urn. There’s already a lot of space waste zipping around up there.

Ashes To Starstuff

We can’t say for certain the absolute first person’s remains to be buried in space. In 1994 NASA confirmed that Gene Roddenberry had actually been buried in space prior to his flight with Celestis. A NASA astronaut had quietly smuggled his ashes aboard an unnamed space shuttle flight as a “personal affect”. At the time the NASA spokesperson believed such a move was a first, but who knows what other astronauts had up their sleeves.

To date official space burials haven’t involved full corpses. Volume is precious on spaceflight. So funeral services send up a “symbolic amount” of the deceased.

That dovetails with the current trends of burials. Since 1999, according to The Cremation Association, the rate of cremations in Canada and the United States has almost doubled. The group expects cremations to account for half of all US burials by 2018.

The reasoning seems tied to changing traditions. The Cremation Association shows states with the highest rates of cremation are also those with the highest rates of people being unassociated with a religion. That’s correlation, but it’s not hard to see how someone would find spreading ashes at a loved one’s favorite spot in the mountains — or in the sky — more sacred than a burial plot at grandma’s church.

“The American funeral industry has long influenced how and where we bury the dead,” notes urban planner Ruth Miller in a paper arguing for more environmentally conscious burials.

Cosmic Pricing

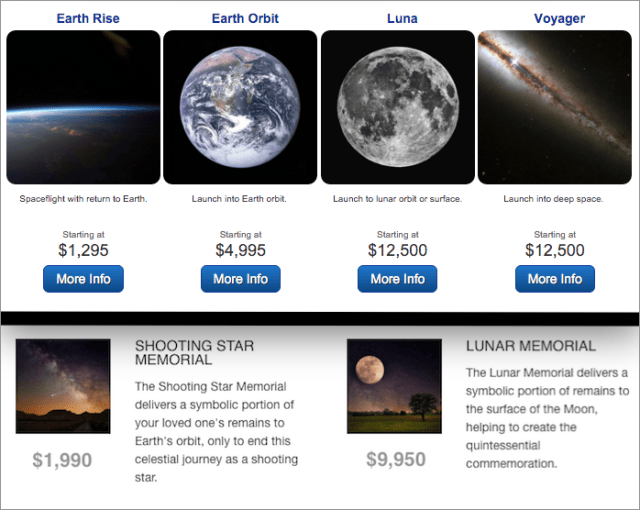

Screenshot of Celestis pricing above, Elysium below

There are a lot of ways to slice price shopping for a space burial. Since flight constraints still mean we can only send a “symbolic amount,” the allowed amount of the departed has changed over time. At the time of Leary and Roddenberry’s journey Celestis charged $4800 per reservation. The symbolic amount at the time was 7 grams.

Today? Depending if you want to orbit with Celestis or Elysium, the costs in absolute dollars are in the same ballpark. But (unless you want to pay for more ashes) the cost per weight has gone up. Celestis’s prices above are for a single gram. So you’ll need to have a plan for the non-astronaut ashes. Depending on the deceased’s body type, a cremation leaves between five to eight pounds of ashes.

But for a family that cares more for the ceremony than having all the remains in one place, how does that stack up to a standard funeral? The National Funeral Director’s Association says the median price for a traditional memorial — casket, viewing, burial and extra services like embalming and a hearse — ran at $7,181 in 2014, a 28.6 percent bump from 2004. A standard cremation service costs about a thousand dollars less — the difference found in not having to buy and bury a casket.

So if the cremation, which has an average standalone cost of about $2000, is part of the equation no matter what, then the price difference between sending a loved one into the ground or into orbit still aren’t light years apart.

It’s hard to assess where these prices go in the future. How will the demand for sending crafts into space change? How will the supply of rockets change? Will competition for space from other sectors — research, technology, climatology — start crowding rockets and, with bigger budgets, edge up the price of a space burial?

The Dead Man In The Moon

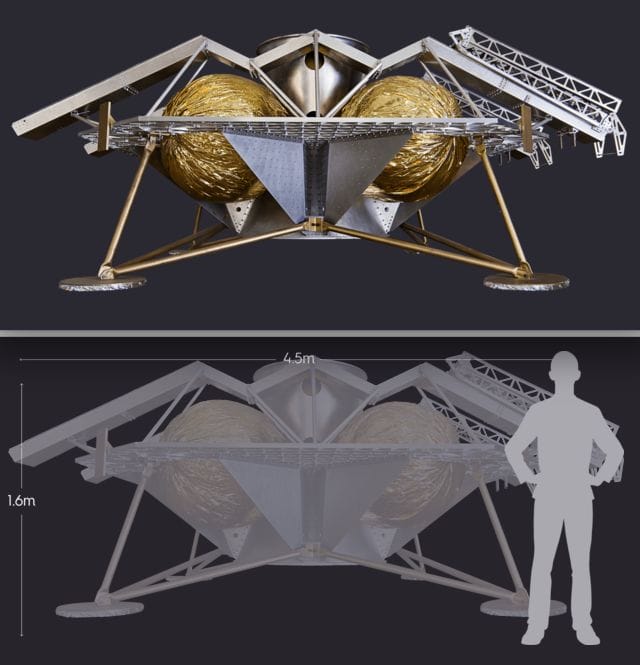

Astrobotic’s Griffin Lander

Sometimes the dearly departed was more interested in the moon, or perhaps a family just wants to look up each night and feel that person is there, watching down on them. Celestis already sent Dr. Eugene Shoemaker’s remains to a crater in the lunar south pole in 1999. So you can’t be the first. Since, there hasn’t been too much room on crafts to get ashes to the moon. But now with incentives like Google’s Lunar Xprize opening up the field of crafts destined for the moon, that’s changing. Celestis and Elysium plan to send batches of ashes with Astrobotic. Thornton doesn’t anticipate the launch will be any earlier than the end of 2017 and hopes the journey will begin on one of SpaceX’s Falcon 9 rockets.

Astrobotic’s crafts are designed to soft land (not crash land, as many other crafts have) on the moon and deposit payload. The company also offers its “MoonMail” which let’s people fly a keepsake — wedding ring, photo, DNA sample — to the moon. Unfortunately for now the crafts won’t return to Earth. A picture of the object in a capsule on the moon will have to supplant showing it to people.

There is little regulation about actually landing on the moon. Obviously no country owns it and there is only a failed treaty, loosely based around the laws of the sea, that has attempted to govern moon travel. The United States and other space-born countries have not ratified it.

“It’s closer to the wild west up there,” Thornton says. That doesn’t mean countries have out six shooters, though. There’s still plenty of room. “As long as we’re not interfering with each other there’s no issue.”

And Beyond

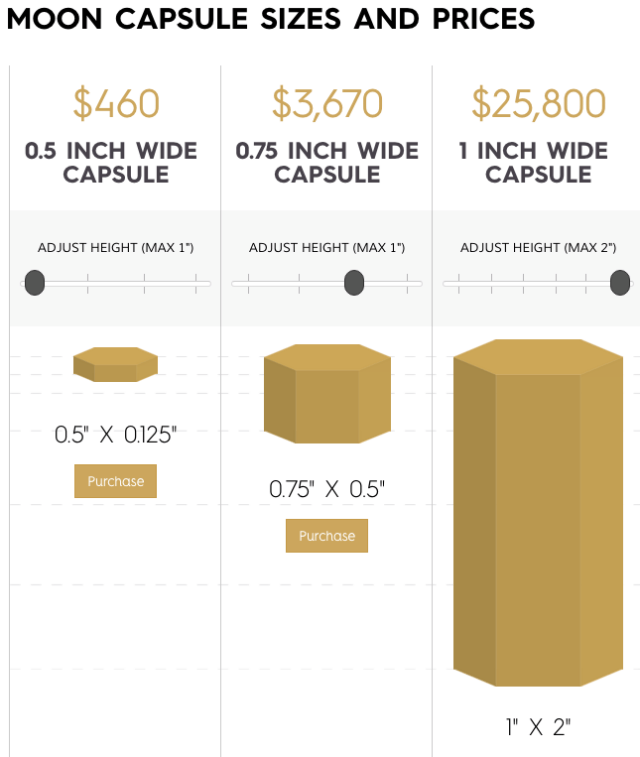

Some MoonMail pricing

But some dearly departed gazed far beyond the moon, out to deep space.

Celestis’s Chafer said the company had been lined up to send remains to deep space on the Sunjammer flight in July of 2015, but NASA cancelled the launch. Celestis has plans for another deep space memorial but can’t announce the details just yet.

Humankind, however, has memorialized a human out in the deep already. When NASA’s New Horizon space craft passed Pluto in July of 2015, some of Clyde Tombaugh’s remains, the planet’s discoverer, were onboard. He didn’t touch the surface, but passing within eight thousand miles was still a pretty nice memorial.

“As we take humans to other parts of the solar system,” Chafer says.”We’re going to take our rituals.”

![]()

This post was written by Caleb Garling. You can follow him on Twitter at @calebgarling.

In our next post we take a look at why U.S. copyright law magically changes every time Mickey Mouse is about to enter the public domain. To get notified when we post → join our email list.