“Ever since man became sapient he has devised means of intoxicating himself”

-Ian Spencer Hornsey’s A History of Beer and Brewing

In 1990, Cambridge archaeologist Dr. Barry Kemp unearthed Queen Nefertiti’s Royal Brewery buried beneath the Egyptian sands. There, he found ten brewing chambers containing ancient beer residue. With the help of some electron microscopy, the 3,250 year-old recipe was identified. In 1996, one-thousand bottles of the resurrected “Tutankhamun Ale” were sold for $75 a pop.

Today, you could brew six-packs of this ancient beer in your kitchen for under $100.

In fact, with just a few weeks and surprisingly little effort, one could brew almost any kind of beer imaginable. Chocolate Stout? Done. Blueberry Pilsner? Of course. Seaweed Ale? Why not? Want something with over 20% alcohol by volume? No problem.

The possibilities are endless, and unless one’s hops were grown on the International Space Station, the cost of brewing beer from home is competitive to or cheaper than buying the quality stuff in the store.

Americans have woken up and discovered that beer doesn’t need to taste like weak, pale, carbonated cornflake water. Over one million people in the United States homebrew, and thousands more take up the hobby each year. A love of craft beer culture has led an increasing number of homebrewers to daydream of quitting their desk jobs to take a shot at starting their own brewery. How hard can it be?

The Resurrection of an American Tradition

Beer has strongly influenced (pun intended) the United States. One popularly circulated myth claims that the Pilgrims landed on Plymouth Rock, instead of continuing to Virginia, because they were running out of beer.

We do know that almost all the founding fathers were avid homebrewers. Just look at the two dollar bill to find three of them: George Washington, Thomas Jefferson and Samuel Adams. James Madison even entertained starting a federal brewery and appointing a “Secretary of Beer.”

Alas, the federal brewery was never created. But in the founding fathers’ day, it was unnecessary. As Jefferson put it in 1816, “The business of brewing is now so much introduced in every state, that it appears to me to need no other encouragement.”

George Washington’s Recipe for Small Beer, ca. 1757. (Courtesy New York Public Library)

In 1919, however, Prohibition struck a blow to the American brewing tradition by making the production, distribution and sale of alcohol illegal throughout the United States.

It wasn’t the end of beer in America, but it was a bigger setback than many realize. When the 21st Amendment ended Prohibition in 1933, it only legalized home-wine making. A clerical error omitted the very important phrase “and beer.” This meant that while breweries selling beer could open for business, homebrewers remained outlaws for another forty-five years until President Carter signed amending legislation in 1978.

For some Americans, the wait has been even longer. Because the federal statute left brewing laws up to each state to determine individually, states have been legalizing homebrewing in waves ever since. Homebrewing did not become legal in all 50 states until this July.

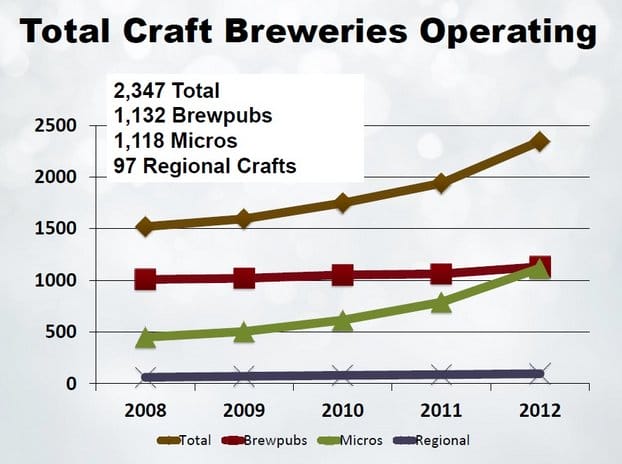

This partly explains why we’re now enjoying such phenomenal growth in the industry. Over the past thirty-odd years, the number of homebrewers in America has skyrocketed to over one million and the number of craft breweries has grown by almost three-thousand percent. Now, a brewery opens for business almost every day of the year.

Source: Brewers Association

Putting the “Craft” in Craft Beer

As “organic” is to food, “craft” is to beer. But besides benefitting from the caché that comes with being known as a “craft brewery,” the distinction entails special tax rates and often franchise laws that can help a brewing company compete in what would otherwise be an oligarchic marketplace.

Just as soda is dominated by Coca-Cola and PepsiCo, Anheuser-Busch InBev and SABMiller dominate the beer market. Each produces hundreds of millions of barrels of beer per year. Together the two make 90% of all beer sold in the United States.

The “Big Two” have also bought up hundreds of other beer companies in what some call the “Beer Wars.” Stella, Hoegaarden, and even Leffe (which was founded in 1240) are now all owned by the same company that makes Budweiser.

The Big Two have responded to the surging popularity of craft breweries by producing what many call “crafty beers.” Beers like Shock Top and Blue Moon deliberately mask their parent company in an attempt to gain brand association with the craft beer movement. Even the “Craft Brew Alliance,” which owns Redhook Brewery, Widmer Brothers Brewing, Kona Brewing Company and Omission Beer, is controlled by Anheuser-Busch through its 32.2% stake in the conglomerate.

In order to better serve and protect craft brewers and the “community of brewing enthusiasts,” the Brewers Association, a trade group of over 1,900 brewers, defines “craft” operations by three criteria. A craft brewery must be small, independent and traditional.

How small is small? A brewery is considered small if it produces no more than 6 million barrels of beer per year. That’s 186 million gallons of beer, or almost one-and-a-half billion pints. In practice, this translates to anything the size of Sam Adams or smaller. The cut-off point has increased over time to accommodate the growth of the largest craft breweries, and the Boston Beer Company (the maker of Sam Adams) is the largest. Although $600 million in annual sales, distribution to thirty countries, a listing on the New York Stock Exchange, and a billionaire CEO may not sound “small,” it is small relative to the makers of Budweiser and Miller.

As the Big Two have sought controlling stakes in craft breweries, “independent” means that no more than 25% of a craft brewery can be owned or controlled by an entity that is not itself a craft brewery.

To ensure that the craft brewery distinction stands for quality – and not merely market share – breweries cannot cut costs by relying on cheaper ingredients like corn or rice. To meet the “traditional” requirement, breweries must feature malted barley grain as the primary ingredient in their flagship beer, or in at least 50% of their total beer production. If the brewery decides to use other ingredients to provide the fermentable sugars necessary to brew their beer, then these “adjuncts” (e.g., corn, oats and rice) must be introduced to “enhance rather than lighten flavor.” An unwritten code stipulates that brewers should emphasize a great product built on bold artisanal choices. Someone selling forgettable beer on the strength of great marketing just doesn’t get it.

Starting a Craft Brewery

An aspiring brewer has three options: a brewpub, a microbrewery, or a contract brewery.

Brewpubs are restaurants that produce and serve over 25% of their beer on-site over the counter. Microbreweries, by contrast, sell over 75% of their production in bottles or kegs that are distributed to restaurants, bars and retail vendors. Contract breweries do not own their own equipment or even have their own location. Instead they hire other breweries and brewers to produce their beer.

Each business model has its pros and cons, although none can escape the business concerns and logistics (like where to dispose of the hundreds of pounds of used grain after brewing) or regulations (alcohol is one of the most regulated industries in the economy) that come before the enjoyment of a profitable venture and the romance of brewing a beer that one designed oneself.

Brewpubs: From the Ground Up

A brewpub is probably what most people think of when they imagine the romantic ideal of starting a brewery. It is a physical location, like a restaurant, but one that serves beer made on-site. Brewpubs also often take pride in their local communities by hosting events, featuring local artists or taking active roles in charitable fundraisers.

Serving beer to regulars is deeply rewarding. It also has economic benefits. The average price for one pint of craft beer sold on draft is around $5. This high price-point generates higher profit margins that can float a small scale business. Many successful brewpubs have a 7 or 15-barrel brewhouse producing anywhere from one to 4,000 barrels of beer per year – the equivalent of a relatively modest 650 to 2,700 pints per day.

Opening a brewpub is a lot of work. It’s like starting two ventures at once: a restaurant and a brewery. Not only does this require mastering two businesses, it also requires hefty up-front costs. It calls for a prime location, which means high rent. Brewers have to pay for salaried employees and open and operate a fully functional kitchen and brewery. And while brewpubs may do well compared to the failure rates of restaurants, brewers are opening a restaurant.

The above notwithstanding, brewpubs have been the most popular type of craft brewery. But new players are choosing other routes to enter the market. Last year, only 99 brewpubs opened compared to 310 new microbreweries. Of the craft breweries to close, 25 were brewpubs while only 18 were microbreweries.

Source: Craft Brewing Business

There is likely an element of market saturation at work here. Of the 1,165 brewpubs in America, most have sprouted up in the same cities. The small city of Portland, for example, boasts over ten brewpubs and counting. Meanwhile, regular restaurants are catching on to the trend by expanding their on-tap and bottle inventories to satisfy expectant customers. As Bart Watson, staff economist of the Brewers Association, points out, “How many neighborhoods could take another restaurant with amazing beer?”

Brewpubs, in short, require lots of capital up front and a willingness to master the restaurant and brewing business at the same time. But brewers that succeed don’t just create beer, they create community. They also get to oversee their beer from choosing ingredients to watching their customers enjoy it over a meal.

Microbreweries: All about Product – and Scale

The success of brewpubs over the last few decades has made it harder to launch a new brewpub. The success of brewpubs and microbreweries, however, appears to have made it easier to open a microbrewery. Bart Watson explained to us, “In the nineties if you went to a major retailer, they’d probably laugh in your face if you told them you had a microbrew.” Today though, “people have paved the path.” The establishment of craft beer culture by its pioneers has created a market of restaurants and retailers looking to sell the wares of new microbreweries.

Without the distraction of running a restaurant, microbreweries can focus on their product. But as they sell at least 75% off-site, their success or failure revolves around distribution – their ability to get their beer to market in kegs for serving on draft in bars and restaurants, or sold in bottles or cans wholesale to retailers.

In either case, this most commonly happens through the “three-tier system”: beer moves from the supplier (the brewery producing the beer), to a distributor (sometimes called the “wholesaler”), and then to the retailer (bars, restaurants, and liquor stores). In many states, the requirement for a brewery to distribute through an independent wholesaler is mandatory. In fact, in some cases, the state itself is the distributor.

The three-tier system dates back to the 21st Amendment and a desire to bring accountability to an industry known to use prostitutes as a marketing tool (to lure drinkers into brewers’ saloons and tied houses) and to generate revenue opportunities (in the form of state taxes). But it has resulted in a byzantine mess of regulation. Every state has different rules, not to mention inter-state distribution laws, and franchise regulations regarding where and when a brewery needs to use a distributor, all of which make it difficult for entrepreneurial brewers to avoid spending money on a lawyer.

This can trip up some microbreweries, especially new ones with small operations. The three-tier system puts more degrees of separation between the producer and the end-consumer, which narrows profit margins. Whereas an over-the-counter pint might go for $5, a keg (serving approximately 130 pints) might sell to a distributor for $85.

To make up for the narrow margins, breweries have to produce in greater quantity. But this means more equipment and more ingredients. The cost of setting up just a 30-barrel system (which is not much bigger than most brewpubs) can run upwards of one million dollars. Finding ingredients of high quality, especially of hops, can become a barrier. Some breweries have contracts 3-5 years out. For the best strains of hops, the wait can be years.

A small, little microbrewery may sound idyllic. But the economics of distribution demand that brewers scale with the intensity of a technology startup. Lagunitas Brewing Company, for example, started on a 7 barrel operation in 1993. They quickly doubled their brewing capacity in 1995, only to expand again in 1999, 2007 and 2012. Over the brewery’s 20 year history, the founders refinanced their house four times to pay for equipment. They even went into debt with their glass and grain companies. While Lagunitas is now one of the most well known craft breweries in the market, it did not turn revenue positive until 2010.

To avoid these problems of scale, many start-up microbreweries try to distribute their beer themselves. This practice, known as “self-distribution,” is allowed in some states, including California. While it requires more time and effort on the brewer’s part to drive kegs to nearby restaurants, removing the middleman means more revenue. When starting out, this can create a realistic opportunity to launch without breaking the bank on large-scale equipment.

Bart Watson, staff economist of the Brewers Association, stresses this point: “Finding out how you can distribute in your state is probably number one on your list. If you can self-distribute, you have a lot of opportunities for various business models to get off the ground.” Of the seven states with the greatest increase in active brewer permits, six currently allow some form of self-distribution.

Source: Beer Institute

This isn’t to say that self-distribution is some kind of panacea. Even where allowed, self-distribution is often limited to breweries of certain sizes, or capped at certain quantities. Brewers that self-distribute still have to deal with buying or renting kegs, processing paperwork to meet labeling and other regulatory requirements, renting or buying bottling equipment and driving around to deliver product to clients. And win over those clients in the first place.

While we have neatly delineated brewpubs from microbreweries, brewers are increasingly turning to hybrid business models to get the best of both worlds. Taprooms – although not legal in every state – allow a microbrewery the chance to augment their distribution business with a small on-site bar for minimal rent. Similar to how wineries can sell a few bottles on location, taprooms give customers the chance to drink a pint on draft or purchase a growler of beer to take home.

Such is the case with Baeltane, a new (and dog-friendly!) brewing company in Novato, California. By combining taproom sales and self-distribution, they’ve been able to open a nano-brewery working off a three-barrel brewhouse – under half the size of even small brewpubs. The combination made all the difference in getting started.

Yet, they still need to expand. They sell their French, Belgian, and West Coast ales as fast as they can be made, but even with the added revenue from self-distributing and opening a taproom, Baeltane has yet to see a profit. They even lose money on their top beer: a double IPA called “The Frog that Ate the World.”

We spoke with Alan Atha, co-founder and brewmaster of Baeltane, who confided that “even if we doubled capacity, I’d doubt we’d be revenue positive.” Baeltane is growing its capacity in stages to eventually become a 20-barrel microbrewery. While the hybrid model doesn’t float their nano-operation at present, it does give them the chance to grow their business gradually without incurring unmanageable debt. Without friendly legislation allowing taprooms, startups like Baeltane might not otherwise have the opportunity to grace us with their unique and tasty brews.

Contract breweries: the Lean Brewing Startup

Contract brewing stands out among the craft brewing scene in that it allows aspiring brewmasters to start a brewing company without a brewery. Instead of putting an initial investment towards rent or expensive equipment, start-up funds are spent on ingredients and contracts to pay other breweries to make the beer.

The Headlands Brewing Company has begun to make a name for itself in and around San Francisco this way. The team wanted to start a microbrewery, but realized from their experience in the industry that they needed to produce at scale in order to reach profitability. So, they decided to first test their product on the market with under $100,000. They contracted out the 30-barrel system of an already established brewery to make their first batch. Within their first month, they were profitable.

Contract brewing comes with its own uncertainties and inefficiencies. By not owning equipment, the contract brewer is entirely dependent on the schedule of the brewer they hire. This makes it challenging to create lasting relationships with clients as retailers, especially bars, depend on the regular and reliable delivery of product.

Also, contract brewers don’t get to brew their own beer. Instead, they just send ingredients and instructions. This distance from the process of actually crafting the beer, which is presumably why one’s in the business, also leads to challenges in controlling taste and flavor. As Inna Volynskaya of Headlands Brewing told us, “Everyone uses different systems, so who you work with is important. Especially when something as simple as the shape of a fermenter can change how the beer tastes.”

To alleviate some of these concerns, a few brewers have entered into “alternate proprietorships” wherein a single brewing facility is shared between multiple brewing companies who use the equipment on a rotating basis. Unlike contract brewing, each partial owner gets to be hands-on and brew their own beer, although it still limits a company’s production capacity. Still, for those looking to supplement an existing operation, or who want to break into the market, alternate proprietorships or contract brewing deals offer an initial way to do so with lower up-front risk. With the market for brewpubs seemingly saturated and the scaling of distribution-based microbreweries often prohibitively expensive, contract brewing could be key to keeping up the influx of fresh blood into the American brewing scene.

Conclusion

The barriers to entry have never been lower for someone wanting to try their hand at brewing beer. Drawing from homebrewing videos and affordable homebrew kits, anyone can fashion their ideal taste: adding roasted coffee beans, medicinal herbs, or pumpkin and spices to craft their one-of-a-kind brew.

But the ease of homebrewing hides the sacrifice and hard work needed to make it as a master brewer.

Brewpubs are social ventures allowing brewers the chance to share their creations while becoming a fixture of their community. Overseeing the process from production to purchase entails high profit margins but also up-front risk. With a brewery and a restaurant, there are two ways to fail. The draw of an in-person location also carries with it vulnerability to nearby competitors in an increasingly saturated market.

Microbreweries are increasingly popular, especially as state laws become more hospitable. Yet, even with self-distribution and taprooms, smaller microbreweries have to scale the size of their brewing capacity to make a profit. The equipment costs necessary to float a sustainable microbrewing business are significant.

A clever way to test for demand and get started without too much early risk or capital investment is contract brewing. Brewers lack control over production, don’t get to brew their beer themselves, and can’t reliably produce at great scale. But it is the quickest route to seeing a return on investment and an appealing way to experiment and enter the market.

These distinctions aside, brewing companies, like the craft beers they make, are transforming rapidly as brewers turn to scrappy and innovative tactics. These methods – fundraising through Kickstarter, offering equity based crowd-investing options, or employing subscription based business models – suggest the promising possibility for leaner minimum viable breweries that facilitate the entrance of new brewers into the industry. Innovation in brewery financing could be just as crucial as innovation in beer production to the health of the American beer scene.

So far, we’ve spent a lot of time addressing some of the how’s surrounding craft beer. But why is there a craft beer movement? And why now?

Certainly legislation played a role, with homebrewing being legalized on the federal and state level over the past decades, and local governments’ attitude toward beer producers transitioning from one of antagonism during the Prohibition era to one of support today.

Yet, after becoming acquainted with the more intangible aspects of the craft beer culture, we see its rise reflecting a broader cultural and economic movement. A movement reflected in other trends like the organic, fair-trade, and slow food movements.

Before the rise of craft beer, the American beer scene was best characterized by the Walmart model. Two giant corporations competed to produce a few generic, one-size-fits-all beers at a low price and deliver them from their factories to every corner of America.

Craft breweries are not immune to economies of scale and the hard logic of running a business. But the craft beer movement emphasizes quality over quantity, community over convenience and personality over homogeneity. It’s a rejection of the Walmart model, or at least the point at which the wave finally broke and rolled back.

Some scholars postulate that beer gave us civilization, providing early humans with the impetus to settle down and end nomadic life when they discovered the delicious and transformative possibilities of fermented grain, as well as the means to overcome our herd mentality for the sake of “exploration, artistic expression, romance, inventiveness and experimentation.” Today beer is the third most popular drink in the world after water and tea, and its role in cultural life seems strong as ever.

What is being crafted by the craft beer movement is so much more than the beer.

This post was written by contributor Phil Balliet. To get occasional notifications when we write blog posts, sign up for our email list.

During the course of this research, this author had the chance to meet with and speak to some wonderful brewers. We would like to thank Baeltane Brewing Company, Headlands Brewing Company, Marin Brewing Company, Lagunitas Brewing Company, and Bart Watson of the Brewers Association for their support, time, information, and amazing beer.