![]()

In their 1997 hit song “Tubthumping”, the band Chumbawamba triumphantly sings: “I get knocked down, but I get up again. You’re never gonna keep me down.” Unfortunately for Chumbawamba, after finding success with this ballad, they did not get up. Instead, the band fell into the pantheon of one-hit wonders, alongside the likes of Soft Cell (“Tainted Love”), Nena (“99 Luftballons”), Biz Markie (“Just A Friend”), and Joan Osborne (“One of Us”). These artists are all especially loveable because they produced one massive, mainstream hit, then seemed to fall off the face of the Earth.

For better or worse, the one-hit wonder seems to be going the way of roller skating rinks and marquee boxing matches: once common, they’re now increasingly rare.

Since 1958, Billboard has released a weekly “Hot 100,” which ranks the “most popular songs across all genres.” Over the years, their ranking methodology has changed to reflect how people consume music; currently, it is measured by radio plays, sales and “streaming activity.”

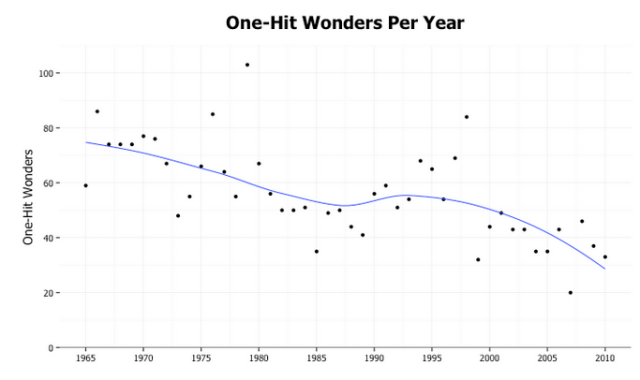

We took this data and analyzed it for the number of Billboard Hot 100 songs in a given year by artists that never appeared in the Hot 100 again. In the chart below, each point represents the number of one-hit wonders in a given year. (It’s worth mentioning that the counts from 1965 to 1970 may be slightly inflated because these early one-hit wonders might have had a hit prior to the establishment of the Hot 100.)

Clearly, one-hit wonders are an endangered species. But why?

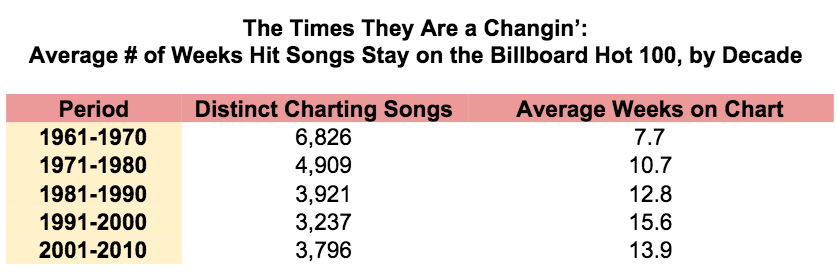

A primary culprit for this decline is a general decrease in the number of distinct songs that appear in the Hot 100 each year. Simply put, songs now stay on the chart longer, which does not allow for as many hits. Prior to 1985, no song had ever stayed on the charts for more than 50 weeks; this now happens regularly. Sam Smith’s Stay With Me is on week 54 and is likely to stick around for a while. In contrast, The Temptation’s 1965 number one hit “My Girl” was only in the hot 100 for 13 weeks. Since the average Katy Perry song stays in the Hot 100 nearly three times longer than the average song by The Beatles, there isn’t too much room for one-hit wonders these days:

Is the music industry repeatedly forcing the same songs down our throat, or is it simply giving its consumers what they want?

It’s tough to say, but we would lean towards the latter. In a recent article, The Atlantic argues that while record labels used to be able to determine which songs would become radio hits, stations now rely more heavily on consumer preferences. In short, iHeartMedia, the conglomerate that owns 850 radio stations, doesn’t care about the desire of the music industry for a quicker hit cycle so they can sell more units. They just don’t want you to change the channel — and the best way to keep you tuned in is to keep playing the same songs.

George Howard, a professor at the Berklee College of Music, does not see this as a consumer driven paradise. He observes a world in which big record labels have as much control as ever: rather than paying the stations directly, they now use independent promoters as intermediaries to pay for radio plays they know will get you hooked. With fewer opportunities to push music on us at music stores like Tower Records and Sam Goody, it’s likely that labels have increasingly focused on controlling mainstream radio, leading to greater homogeneity.

***

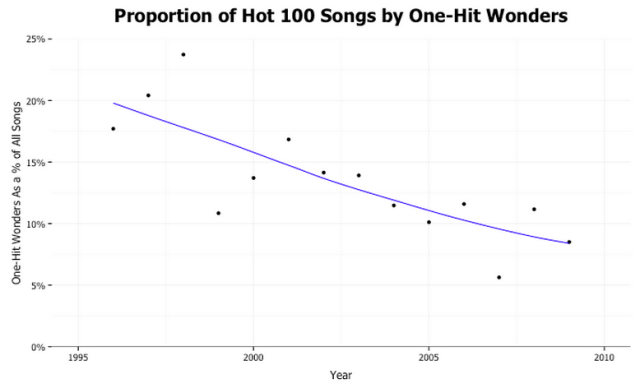

But this general decrease in hits does not entirely explain the dwindling nature of one-hit wonders. Since 1995, one-hit wonders have also declined as a proportion of songs that make up the Hot 100.

From 2005 to 2010, the fraction of songs by artists that never made the chart again hit an all-time low. It’s important to keep in mind that these numbers are conservative, as several of the bands that generated these possible one-hit wonders could still hypothetically produce another hit someday. In other words, UGK still has a chance to write another “International Players Anthem” and scale the charts again (note: as one reader points out though, this particular chance is extremely unlikely).

This could likely be attributed to an increased reliance on brand-name artists. Just as the movie industry seems to be relying more heavily on sequels, the music industry is putting more emphasis on promoting established artists. In a turbulent marketplace, record companies are liable to be more risk averse. Developing new artists who might hit it big is less appealing when the prize is projected to get smaller.

One may also attribute this decline to artists’ enhanced abilities to cultivate their brands and fan bases in the Internet era. It’s easy to see a world in which Carly Rae Jepsen disappeared into a Jennifer Paige-like obscurity following Call Me Maybe. Instead, she is back in the Top 40 three years later, and Tom Hanks is lip syncing her songs. It couldn’t have hurt that she’s been charming millions of followers over the last several years on Twitter, Facebook and Instagram. Whereas it would have been nearly impossible to maintain this kind of intimate relationship with fans ten years ago, it’s now par for the course, as well as good business.

***

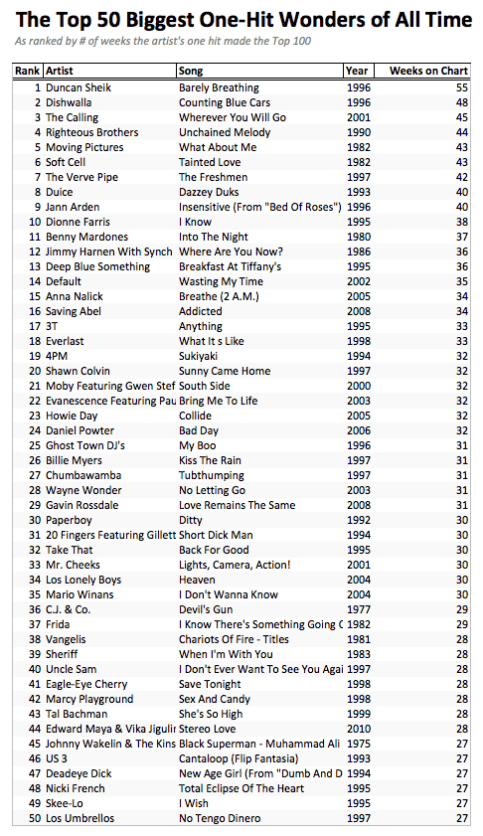

Perhaps the one-hit wonder should disappear. Artists are less likely to find long-term success today, but they are also less likely to have a moment in the sun they can never replicate. Will there ever be another Dishwalla or Marcy Playground or Duncan Sheik?

Still, it feels like our culture is losing a particularly pleasurable phenomenon. By their very nature, one-hit wonders are bound to the time period in which they experience success: Dexys Midnight Runners (“Come on Eileen”) will forever be linked to the 80s, just as Chumbawamba (“Tubthumping”) is a quintessential part of 90s lore. They are highly nostalgic ballads of our past, and are universally beloved. When VH1 aired a special on the “100 Greatest One-Hit Wonders”, it was so popular that they went on to produce decade-specific versions like “100 Greatest One-Hit Wonders of the ‘80s”.

So let us never forget the greats — The Proclaimers (“I’m Gonna Be (500 Miles”), Deep Blue Something (“Breakfast At Tiffany’s”), and Los del Rio (“Macarena”) included — because soon, there may not be new one-hit wonders to replace them.

![]()

This post was written by contributor Dan Kopf. To get occasional notifications when we write blog posts, please sign up for our email list.