“I think the message I deliver is a good one. And that message is: you’re supposed to be a responsible citizen.”

– Judge Judith Sheindlin, a.k.a. Judge Judy

![]()

Judge Judy is known for her quick rulings, pithy sayings, and forceful personality, and it is hard to think of a judgment as quick, a saying as pithy, or a performance as forceful as the case she settled in only 26 seconds.

“I had to replace all my IDs,” said Ginny Paradeza, as she explained that the two men in the courtroom had stolen her purse. “I had gift cards in there, an earpiece, and a calculator.”

As she spoke, one of the defendants interrupted. “There was no earpiece in there ma’am,” he told Judge Judy.

The courtroom laughed. By calling Ms. Paradeza a liar, the man had revealed that he’d stolen her purse. Judge Judy smiled, pointed to the defendants, and called them “Dumb and dumber.”

“Judgment for the plaintiff in the amount of $500,” Judge Judy concluded. “Goodbye.”

The case is one of thousands that Judy Sheindlin has settled as the host of Judge Judy, a reality television show that first aired in 1996. The cases are minor but real, drawn from the country’s small claims courts.

The 20-year run of Judge Judy has been one of the most remarkable in television history. It has had the highest ratings of any daytime show for the last 5 years, and it consistently attracted more viewers than Oprah. Sheindlin makes $47 million a year and has a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame.

Sheindlin has enjoyed her commercial success; she also says she uses her show to teach lessons. “If I could define it in one word,” she has said of her message, “it’s responsibility. People really want their fellow man to accept responsibility for themselves and their actions.”

Sheindlin reiterates the theme of responsibility and accountability over and over. In interviews, she lambasts a welfare state that tells people “not to worry, if you can’t take care of yourself, we’ll take care of you.” On her show, she gives a tongue lashing to defendants who make excuses and reprimands victims who exercise poor judgment.

Accountability is her thing, and like most of what you see on television, it’s mostly an illusion. Because as even Judy Sheindlin has acknowledged, after she admonishes guilty defendants and orders them to pay for what they’ve done, the producers write a check to pay for those damages and give everyone in the case an appearance fee.

In other words, the producers help the defendants avoid accountability.

This does not mean Judge Judy has no substance. In fact, few people have earned the right to moralize as much as Judy Sheindlin.

Before she played a judge on TV, Sheindlin was the supervising judge of the Manhattan Family Court. In one of her hardest cases, she had to decide whether a 14-year-old mother was guilty of murder after her baby was found dead in a toilet. This is the context where she first preached responsibility.

But once she moved to television, Judy Sheindlin started chastising rulebreakers even as her show absolved them of responsibility.

The Incredible Career of Judith Sheindlin

Judy Sheindlin’s early life reveals few hints that she would become the queen of daytime television.

She grew up middle class in Brooklyn. Sheindlin has described her time in high school as an “unremarkable tenure,” her mother as a “a meat-and-potatoes kind of gal,” and the idea of being on television as “a fantasy.” She expected to be a “working girl,” so after graduating from American University in Washington D.C., she enrolled in its law school.

But Judith Sheindlin had the personality of Judge Judy all along. She loved to argue so much that her father believed she would become a politician. Sheindlin has also said that she picked up comedic timing from her father, a dentist who told jokes to reassure his patients. For that reason, when Sheindlin first watched the People’s Court, the first courtroom television show, she believed she could do it better than its sober, analytical judges.

Sheindlin, though, was not in Hollywood. She married while in law school. To meet social expectations, she transferred to a law school in New York, where her husband worked, and prioritized cooking and cleaning over her studies. Despite saying that a woman at the college she attended, the New York Law School, was about “as welcome as a skunk at a lawn party,” she graduated and took a job as a corporate lawyer. But after two unsatisfying years, she quit and became a stay-at-home mother.

It wasn’t a good fit for the future workaholic. To stay stimulated and “do something other than watch daytime TV and take care of kids,” she took graduate courses and attended law seminars at night. At one, a former colleague told her about an opening as a prosecutor in family court. She took the job.

Image via Giphy

Sheindlin found the work rewarding. “I’m a law and order girl,” Sheindlin has said of her time prosecuting and later sentencing mothers who burned their children with lighters and youths who beat cab drivers. “I found my mission.” Ten years later, in 1982, New York City mayor Ed Koch appointed her as a judge. In 1986, she became a supervising judge, in charge of Manhattan’s family court.

It was an important, $90,000 a year job that involved managing nine judges and hundreds of attorneys. Yet family court is distinctly unglamorous. Cases can be gruesome, but since they focus on minors, they exist at the bottom of the judicial hierarchy. Family courts receive fewer resources, and its judges and attorneys handle too many cases. Burnout is common.

Many fans of Judge Judy now wonder whether Sheindlin bullies, insults, and mocks people in her courtroom for the sake of TV ratings. But it’s not an act. She has always bullied, insulted, and mocked the people in her courtroom.

Judy Sheindlin’s rise to fame began with a long profile written about her in the LA Times. In the article, reporter Josh Gelin introduced the world to the character now beloved by millions of fans of Judge Judy.

Gelin described Sheindlin as a “tart, tough talking judge” who told him, “I can’t stand stupid, and I can’t stand slow.” Judge Sheindlin took over the questioning of witnesses when lawyers proceeded too slowly and bullied lawyers so much that one report noted that “attorneys beg her to simply listen to them.”

The only pauses in Sheindlin’s courtroom came when she told jokes, sounding “more like a stand-up comic than a judge.”

The butt of those jokes were often litigants who Sheindlin felt wasted her time or made excuses—a phenomenon captured by Gelin in this memorable exchange:

“Don’t pee on my leg and tell me it’s raining!” she yells at a teen-ager who claims he began peddling drugs after a death in his family. “Nobody goes out and sells crack because Grandma died! Get a better story!”

Sheindlin has said that she always worried the press would describe her as a monster during her tenure as a judge. But Gelin portrayed Sheindlin as a hero who “who won’t give up the fight to help America.”

“Sheindlin’s highly personal crusade to bring order out of chaos,” Gelin wrote, “has assumed folkloric proportions in America’s largest juvenile justice system.”

Former mayor Ed Koch, who made Judith Sheindlin a judge, later starred in The People’s Court. Warner Bros. via NY Daily News

In this light, he views Sheindlin’s impatience as a necessity—given her daily caseload of 40 to 100 trials each day—and a determination to keep the courts moving. He also sees Sheindlin’s disinterest in mitigating circumstances and her defendants’ lives not as a lack of compassion, but as a necessary corrective.

At the time, in 1993, the “Tough on Crime” movement was in full swing. Crime rates were high, and political rhetoric blamed America’s soft court system and unraveling social mores. Reagan had signed a bill that introduced mandatory minimums in 1986, and in 1994, Bill Clinton approved legislation that built more prisons and toughened criminal sentences.

The LA Times article fit Sheindlin into this tough on crime narrative—in laudatory terms.

“The crisis of collapsing families is a national problem,” Gelin wrote. “The hubcap-stealing kid of the ’50s is today’s gun-toting gang member.” Gelin portrayed family court’s “soft” and “compassionate” approach as out of touch with the rough new reality of a crime epidemic, and Judy Sheindlin’s tough approach and focus on personal responsibility as the answer.

The LA Times article attracted more attention, including that of 60 Minutes reporters. They approached Sheindlin, and in 1993, they aired a story that portrayed her in similarly heroic terms.

After she watched the 60 Minutes interview, Sheindlin celebrated by meeting up with friends and buying a tuna fish sandwich. She was fifty at the time, and she has said that she had planned a modest retirement in Florida.

But the entertainment world saw big potential in the tour-de-force judge.

A book agent told Sheindlin that she had to share her message of personal responsibility, and the result was Sheindlin’s bestselling book Don’t Pee on my Leg and Tell Me It’s Raining.

Then a producer with experience in court television told Sheindlin he wanted to cast her in a show. The result was Judge Judy.

The Making of Court TV

By the second season, the success of Judge Judy had inspired competition. Producers re-launched The People’s Court and piloted new series like Judge Joe Brown, Judge Alex, and Divorce Court. None has matched Judy, but court TV is now an established format.

Court TV is not fake, but the setup is not completely honest. The courtroom is actually a set, with hired extras who are paid to banter so the bailiff can say “Come to order!” when Judge Judy walks in. As for Sheindlin, she has not been a judge for decades. During Judge Judy, she serves as an arbiter at a binding arbitration—a private alternative to a court case.

But Sheindlin operates in her fake courtroom just like she did in a real one. She arrives by 8 a.m. knowing the basics of each case, and she hears each in turn. It’s the crews’ job to capture the drama and edit it into an episode. There is no script; there are no re-takes to get a line right; and they film a week’s worth of episodes in a single work day.

The only major differences now are that Sheindlin takes a private jet to work (she flies to L.A. most weeks for tapings) and plays hands of gin rummy between cases to keep her energy up.

Since Judge Judy is an arbitration, it can’t cover criminal cases. People can only agree to arbitration for civil cases (matters of money and property), and Judy’s cases come from small claims court, where people can sue for a maximum of $5,000.

That’s where the producers come in. Along with teams of researchers, they scour America’s small claims courts with the critical eye of a reality television producer.

For an inside look at this process, we turned to Sharon Houston, who worked as producer for court TV for more than 10 years and has chronicled the experience. This is how she has described the process of scouring America’s courts for promising cases:

If you’re from Detroit, Houston, Cleveland, Cincinnati, St. Louis, Kansas City, New Orleans, Indianapolis, Chicago, Milwaukee, Gary, or Atlanta, I’m calling you no matter what the case is about. Why? Because that’s where crazy lives.

I’m also going to call you if you’re suing for pain and suffering, mental distress, mental agony, nightmares, and my favorite, loss of enjoyment of life. I also love it when Plaintiff wants to sue Defendant for being “triflin’.” That’s good stuff!

Her job, Houston says, is to exploit stereotypes. She’s looking for black women suing each other over a hair weave. Booking a mother-daughter pornstar team was a triumph. Scorned women are great. Before the show, producers pump the litigants up like they are boxers in the ring, so they’ll be ready to say horrible stuff about each other.

“It’s what the audience wants,” Houston says. “… it’s weird, it’s so weird.”

To Sheindlin’s credit, Houston says that Judge Judy aims to be “above brand.” (Houston did not work on Judge Judy, but court TV is a small world.) Judy’s producers want drama and some crazy, but not stereotypes or people who will fight all episode. The Judge Judy producers prep litigants by helping them articulate their case.

Why do people go on court TV? “Everyone wants to be on TV,” Houston says. In her estimation, 60% of the people who appear on shows like Judge Judy go for the free trip to L.A. and the 15 minutes of fame.

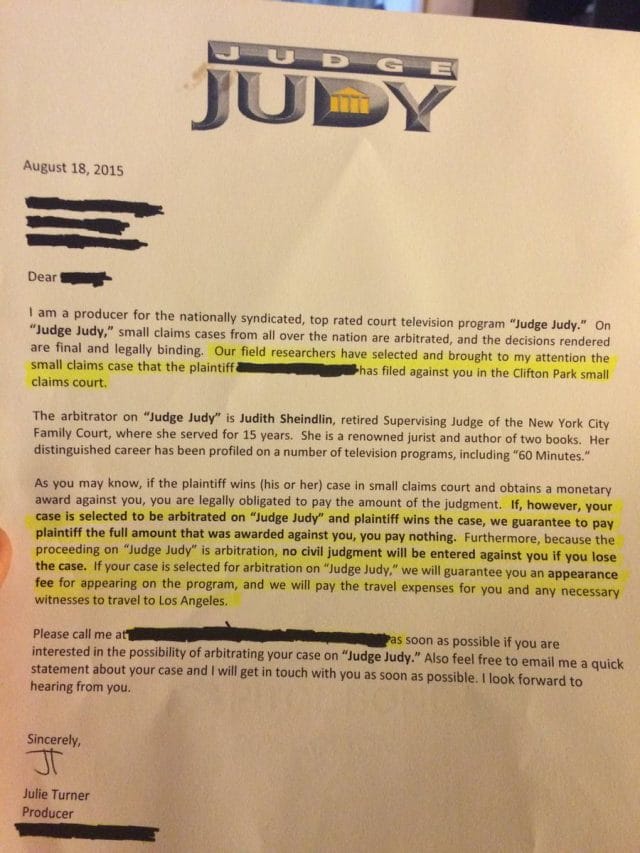

The other 40% of the time, Houston says, people do it for the money. Plaintiffs who know they will win want the quick settlement rather than a long court case. Defendants who think they’ll lose want the show to pay the damages they owe. And in either case, the show pays each person an appearance fee of around $150 to $500 and pays for their flight, hotel and meals.

This aspect of court TV—that when Judy Sheindlin and other judges order defendants to pay up, it’s the producers who actually pay—is an open secret. The media has reported it, citing litigants who appeared on Judge Judy. Sheindlin herself has confirmed it in interviews, and we confirmed it with both Sharon Houston and Sheindlin’s publicist.

You can see an example of this in the below recruiting letter, which was sent by producers to a potential litigant:

Source: Fox4

These promises don’t fit with Judy Sheindlin’s narrative about teaching responsibility. But they do draw people to L.A. for taping sessions of Judge Judy.

It’s no secret that the majority of the people who appear on Judge Judy and court TV shows are poor. People with money don’t sue each other over $5,000, and if they feud in public, they don’t do it on daytime television. But the biggest insight from talking with Houston is fully appreciating the litigants’ poverty.

“I have to ask them if they have teeth,” Houston has said. Most of the litigants, she explains, don’t have a full set of teeth, so the show buys them a pair for their appearance—or paints their teeth if they’re rotten and discolored from drug use. They might also take them to a hairdresser or barber, and they provide clothes that look nice but not too nice.

“If you saw what America actually looks like, you’d be horrified,” Houston says. “You wouldn’t turn on the TV.”

Judging Judy

The most common criticisms of Judge Judy—from both viewers and law scholars—condemn the way she berates and moralizes the poor and unfortunate.

And there is something disconcerting about a well off judge mocking poor defendants for being unprepared or struggling to present their case. “These people have been in a cycle of poverty,” Houston tells us. “It’s just something we don’t understand.”

This isn’t only a matter of sympathy. Eldar Shafir, a Princeton psychologist, has studied how poverty prevents people from solving puzzles similar to an IQ test. “Financial constraints capture a lot of your attention,” he has said. “Then there’s less bandwidth left to solve problems. Your cognitive ability starts to slow down, just like a computer.”

Sheindlin has held a fire and brimstone view of justice since her family court days. (“I want first-time offenders to think of their appearance in my courtroom as the second-worst experience of their lives,” she told the LA Times in 1993, “circumcision being the first.”) Whether you consider her manner and judgments as commonsensical or lacking compassion gets at a fundamental debate about our criminal justice system: should it punish or rehabilitate?

For her part, Judy Sheindlin has criticized judges who speak in fancy, legal language and said that she uses jokes and plain language so that people will understand her judgments and lessons. (“Liar, liar, pants on fire,” she has said, “That people understand.”) In interviews, she explains her lack of interest in mitigating circumstances (or “sob stories,” as she would put it) this way:

“While I recognize that some of the people I prosecuted in family court didn’t have the same kind of advantages I did… I found it almost disrespectful to say, well what do you expect? They come from this type of home. Because 95% of the other children brought up in the same environment did not go out and hurt people.”

What about Judge Judy’s message of responsibility, which seems undermined by her producers paying for any damages that Sheindlin instructs a defendant to pay?

When we asked Sheindlin’s publicist, he responded, “If Judge Sheindlin dismisses a claim, the parties are bound by that decision, and if she orders the transfer of property, the parties are bound to do that transfer. Therefore, there are often very real consequences to her judgments. That’s in addition to some real lessons for the audience.”

This is partly true. When Sheindlin dismisses a case, the case is over by the terms of the arbitration agreement both parties sign. When a court TV judge orders a defendant to return a car or some other piece of property, though, it rarely happens.

“In my experience,” Houston says, “whenever a judge says exchange property, we can’t enforce that. We just pay the judgment.” In some cases, the staff tells the defendants to bring the property to court so they can make the exchange. In most cases, Houston says, producers pay the cost of the property and the defendant keeps the item in question. No accountability there.

That doesn’t mean Judge Judy doesn’t offer resolution or lessons. When people are mad enough to undergo the time and expense of small claims court over a few hundred dollars, the case is usually, like any fight, about emotions as much as money. People can feel vindicated when Sheindlin finds in their favor—or appreciate someone helping them resolve a conflict. Houston has received letters from plaintiffs and defendants, she says, that read “Thank you, I learned something” or “Thank you for making this right.”

Judy Sheindlin is many things. She is the highest paid woman in television, and someone who started her career by throwing off the expectations of motherhood to work her ass off in the unglamorous world of family court. She berates defendants, and she has personally investigated a case when she believed a defendant was incorrectly stripped of her parental rights. Her comments about welfare have led minority groups to criticize her, and she has gone out of her way to ensure that a group of young, white men who beat up a young, black man would face jail time.

When it comes to judging Judge Judy, we can only do it with a nuance she would hate: It’s hard to judge.

![]()

Our next post investigates whether cigarette taxes are unfair to the poor.

To get notified when we post it → join our email list.

Note: a previous version of this article misquoted Sharon Houston as saying that producers of court TV shows referred to the process of getting litigants ready for the show as “going through the carwash.” The term “carwash” is not used by court TV producers; it was a term used on a talk show Houston once worked on. The author apologizes for the error.

This post was written by Alex Mayyasi. You can follow him on Twitter at @amayyasi.