![]()

On August 18th, 1969, at around ten o’clock in the morning, Jimi Hendrix raised his white Fender Stratocaster guitar in the air, gazed out across the mud-soaked crowd at Woodstock Music Festival, and began to play “The Star Spangled Banner.”

Over the previous three days, the dairy farm in rural Bethel, New York had been packed with 400,000 people; Hendrix, the highest paid act at the festival, was the last to take the stage, and only 30,000 remained to witness his tongue-in-cheek ode to America.

For three minutes and 43 seconds, the notes screamed and hissed and squealed from his instrument, voicing the frustrations of the nation’s youth. And right at the center of Hendrix’s iconic sound was a guitar effect called the “wah-wah pedal” (or simply, the “wah”).

Invented in the midst of a musical revolution in the 1960s, the wah became, in the words of one critic, “psychedelia’s non-psychotropic aid.” Rocked up and down, the pedal evoked sounds that mimicked the cries of a human voice, bridging the divide between music and vocal communication. From Clapton to the theme song for cult classic film “Shaft,” the wah immortalized itself as one of music history’s most recognizable and influential technologies.

How did this iconic invention come about? And how did it become such a fixture in popular culture? These questions led us on a long and winding road — one that fittingly begins with The Beatles.

The Beatles’ Amplifier Woes

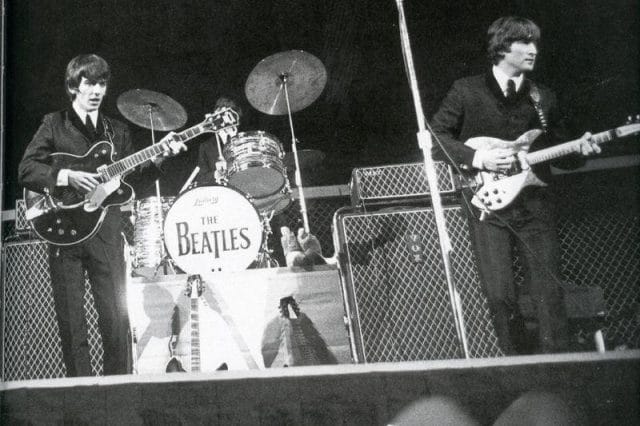

The Beatles performing with their new Vox AC-100 (“Super Beatle”) guitar amplifiers in 1964; via VoxAC100

As The Beatles prepared for their first ever U.S. tour in early 1964, they realized that their technology was inadequate. Over four years, the rock group had established itself as Britain’s favorite quartet, drawing crowds in excess of 10,000 people. Increasingly, screaming fans had rendered their guitar amplifiers completely inaudible during shows.

At the time, the group, like most of Britain’s major acts, was using the Vox AC-30, a 30-watt amplifier made by UK-based Jennings Musical Industries (JMI). When it was brought to JMI’s attention that this model was no longer sufficient for The Beatles, the company designed a 100-Watt version, and affectionately dubbed it the “Super Beatle.” Weeks later, the band — and their new amplifiers — made a successful U.S. debut on the Ed Sullivan Show: 73 million people (34% of America) tuned in to hear them play.

Overnight, “Beatlemania” kicked into overdrive, and the group became massively famous in America. Very quickly, JMI realized that it would behoove them to create a U.S. market for their new amplifiers, and they began looking for a distributor. In August of 1964, they settled on an applicant: a small Los Angeles-based firm called Thomas Organ Company.

Initially, JMI shipped Vox amplifiers to Thomas Organ, but, according to JMI, “the high costs of importing Vox amps from the U.K. severely affected profitability.” An enterprising entrepreneur, the CEO of Thomas Organ at the time, convinced JMI to take a deal: for a one-time payment, his company bought the rights to manufacture Vox products in America.

An Accidental Invention

In 1965, in a small back room of a Los Angeles facility, Thomas Organ’s engineers began to build Vox amplifiers. Among these engineers was a bright-eyed 20-year-old by the name of Brad Plunkett.

Plunkett was given a challenging task by Thomas Organ’s CEO: he was to take apart a Vox AC-100 guitar amp and find a way to make it cheaper to produce while still maintaining the sound quality.

“The first thing I noticed,” he recalls in the documentary Cry Baby, “was this little switch [on the amp] entitled ‘MRB.’”

This switch, invented by British engineer Dick Denney and installed on all Vox AC-100 amps at the time, stood for “middle range boost.” When flicked on, it would highlight the middle sound frequencies of the guitar (notes between 300 and 5,000 hertz); in doing so, it would tame the extremes (very high and very low pitches), and produce a flattened, smoother sound. Plunkett realized that he could replace this pricey switch with a potentiometer — essentially an adjustable knob that divided voltages and acts as a variable resistor — and achieve the same effect.

“The switches were very expensive, about $4 each,” Plunkett continues. “The potentiometer would only cost about 30 cents.”

A potentiometer; via Wikipedia

After a few days of fiddling around with spare parts, Plunkett succeeded in designing a circuit that could change the frequency of notes by simply rotating a potentiometer. Then, something unexpected happened:

“I went next door, and asked a friend of mine to plug a guitar into this pile of wires, resistors, and capacitors I had on the bench. He strummed a few chords while I turned the knob on the potentiometer. It went ‘WAH-WAH-WAH.’ We looked at each other, and said, ‘Wow! This is really great!’”

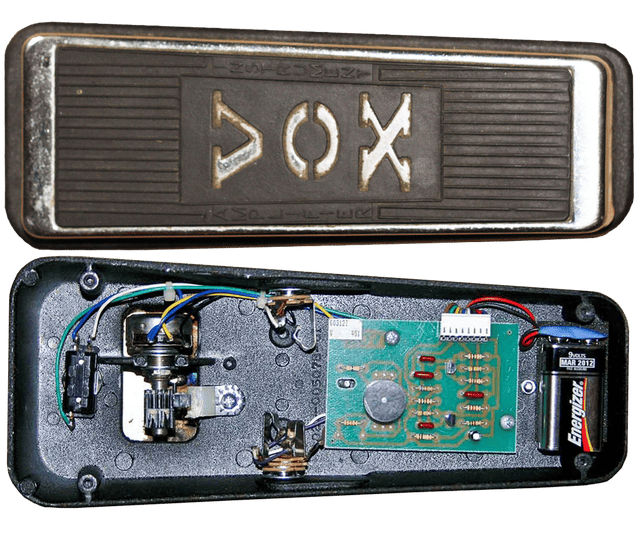

Certainly, it was a groovy, unique effect — but there was no way a guitar player would be able to simultaneously twist a potentiometer knob and play his instrument. Glancing across the room, Plunkett spotted a volume pedal for a Vox Continental organ and had an idea: he grabbed it, gutted it, then wired the potentiometer inside of it with a 9-volt battery. This way, Plunkett was able to control the fluctuation in pitch with his foot.

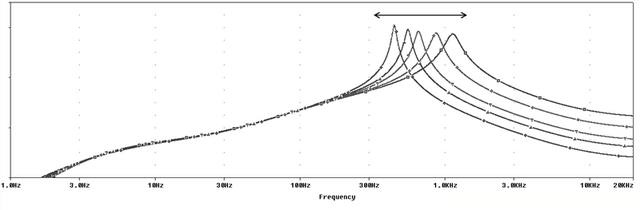

Sound frequency waves of a wah pedal; Via ElectroSmash

The guitar plugged into the pedal, and the pedal lined out to the amplifier, making the contraption an intermediary in which the sound could be manipulated. When the pedal was pushed down, the notes played on the guitar would be filtered at a low frequency; when it was up, they’d be filtered at a high frequency.

“Pretty soon we were drawing a modest crowd [in the office],” says Plunkett. “Everyone agreed that it sounded good, but we didn’t really know how good it was going to be.”

Zappa to Hendrix: How the Wah Took Over Rock N’ Roll

In 1965, electric guitarists really only had four different effects pedals available to them: tape delay, tremolo, spring reverb, and fuzz (distortion). As Art Thompson, senior editor of Guitar Player Magazine, notes in the documentary Cry Baby, “guitar was really popular but had reached a plateau with a lot of pop bands doing the same things.” Musicians were looking for new ways to manipulate and explore sound.

One of these musicians was Del Casher. A studio guitar player for the likes of Gene Autry and Elvis Presley, Casher had just joined the Vox Ampliphonic Orchestra, a troupe of musicians employed by Thomas Organ to market their new Vox products. Here, he came across Plunkett’s early prototype.

“I said, ‘What’s this knob?’ And I’m flipping it around and noticing it’s going wah-wah as I went from left to right,” he recalled in a New York Times interview. “I said: ‘Hold on! This is what I’ve been looking for!’”

Initially, Thomas Organ’s CEO, a fan of big band music, saw the pedal as more of a device for trumpeters, who, for years, had manually created similar “wah”-like effects using rubber mutes. But Casher was insistent that it be marketed to guitar players, and convinced upper management to let him record a demo record showing how it could be used for the guitar.

“They thought I was a crackpot, but they humored me,” Casher joked. “I got my guitar, my prototype wah pedal, and played all the parts myself.”

Though Casher’s record wasn’t a smash success, his use of the strange effect caught the attention of Frank Zappa. The eclectic rocker hired the guitarist and brought him on tour, during which time Zappa became enamored with the pedal.

In February of 1967, Thomas Organ released the wah pedal to the public.

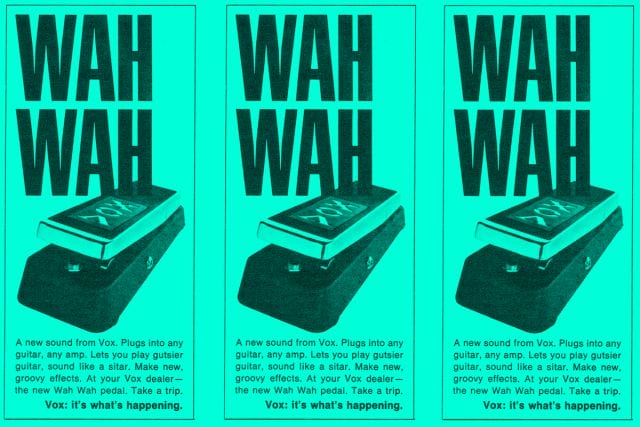

At first, the device was marketed as the “Clyde McCoy,” named after a jazz trumpeter who extensively used a mute to create a “wah-wah” effect in the 1920s. But soon, after a more savvy marketing employee suggested that the pedal sounded like “a baby crying,” it was re-branded as the “Cry Baby.” Because of Thomas Organ’s contractual relations with Vox, two pedals were put on the shelves (one called the “Vox Wah-Wah, and the other, the “Cry Baby”) — both with identical circuitry.

“With the Vox Wah-Wah Pedal, you can play incredible new effects making totally new sounds,” touted one advertisement. “Play the wild Eastern sound of the sitar. Play really ‘funky’ bass guitar. Play groovier blues. Make your instrument growl, baby.”

Early advertisements for the Vox Wah-Wah pedal; via Vox Showroom

“The wah was, to me, the new voice of the guitar,” Casher said in an interview. “The older school of producers and musicians didn’t see the value to using the wah…until the younger people came onto scene.”

Almost immediately after being released, Frank Zappa purchased one, and, according to Del Casher, then introduced it to guitar luminaries like Eric Clapton and Jimi Hendrix.

A rapid succession of big hits prominently featured guitar solos with the wah pedal — first, Cream’s “Tales of Brave Ulysses” in May of 1967. This was followed by Jimi Hendrix’s “Up From the Sky” (1967), “Little Miss Lover” (1967), and “Burning of the Midnight Lamp” (July 1968).

“I think we’ll use it some more on records,” Hendrix told a reporter that year. “It’s got a very groovy sound.” Though other big-name bands used the wah, Hendrix redefined its sonic possibilities — most famously on his 1968 recording, “Voodoo Chile (Slight Return).”

By the end of the 1960s, acts throughout Britain and the U.S. implemented the device into their act, in hopes of latching on to Hendrix’s popularity. In a little less than four years, the wah pedal had gone from a questionable prototype to one of the defining sounds in popular rock music.

“The 1960s were a time of amazing changes in attitude of the music,” explains Rolling Stone journalist Ben Fong-Torres. “When you hear something different, and you’re living in a time that is speaking different languages to you, you take note.”

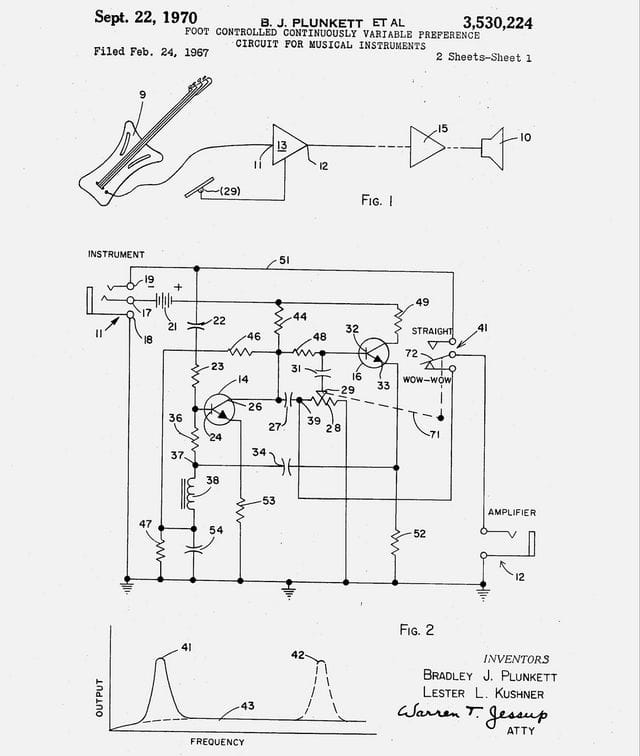

The patent for the wah pedal, secured in 1970, came a little too late; Google Patents

While the wah pedal took advantage of these cultural changes, and gave rock music a new, warbling voice, trouble was on the horizon for its creator, Thomas Organ.

On February 24, 1967, shortly after releasing the device to the public, Brad Plunkett had submitted a patent for the “wah-wah” pedal. Unfortunately, the patent took three years to get approved.

During this time, Warwick Electronics Inc., a much larger company, bought out Thomas Organ. To lower production costs, they decided to shift manufacturing of the wah pedals to Eko, a company in Italy. Here’s where things went horribly wrong.

By March of 1967, the circuitry design for the Cry Baby wah pedal had leaked out of Eko’s production facility, and dozens of imitator pedal brands began popping up all over Europe. Even after Thomas Organ (owned by Warwick) secured the patent on September 22, 1970, they didn’t enforce it: “By the time management realized it was important, everyone was making them,” said one executive, “and it would have been too much of an effort to shut them down.”

With the Vox brand diluted, the wah pedal continued to revolutionize music — and not just in rock.

Shaft and the Funk Wah Revival

In the 1960s, the wah had found its place in searing rock guitar solos; by 1970, it was manipulated by funk, soul, and R&B artists in a completely different way — most notably in the movie “Shaft.”

Part of the 1970s’ “blaxploitation” craze, “Shaft” tells the story of an African-American detective who fights his way through Harlem and the Italian mob to recover the daughter of a mobster. When producers at Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer began work film in 1971, they knew that they needed a fittingly badass theme song. Isaac Hayes, a soul singer who’d recently worked on a string of hits, was hired to fulfill this task.

Subsequently, Hayes put together a group of session musicians, including Charles “Skip” Pitts, who, at the time, was widely regarded as “one of the architects of funk guitar.” Pitts recalls the writing process:

“We were looking for something that would go with [Shaft’s] walk. Isaac told the drummer, ‘Give me some 16th notes.’ I was tuning my guitar, and checking the pedals out. I turned on the wah wah pedal, and was testing it out using a little pattern. [Isaac] said, ‘What are you doing?! Keep playing that! Keep playing that riff! I stayed on the same key the whole time — all through the whole entire damn structure! Didn’t change anything except the structure of my foot.”

The riff — a rhythmic “chika-chika-chika” strumming — would become one of the most recognizable guitar parts in history.

“To me, it seemed repetitious, redundant, and ridiculous,” Pitts later complained. “At the time it came out and I heard it in the car, I still didn’t like what i was doing. I said, ‘Why’d he let me do that shit all the way through the song?!”

Critics reacted differently. Released as a single in 1971, “Theme from Shaft” went on to chart #1 on the Billboard Hot 100, #2 on the BIllboard Soul Single Chart, and #6 on the Billboard’s Easy Listening Chart. In 1972, the song won the Academy Award for Best Original Song, making Hayes the first African-American to ever win the award.

By the end of the decade, the wah pedal could be heard across nearly every musical genre: rock, R&B, soul, funk, jazz, reggae, television jingles — even x-rated movies.

Melvin Ragin, under the moniker ‘Wah Wah’ Watson, became famous for his abilities to play rhythm with a wah pedal and recorded and made appearances on dozens of huge hits like “What’s Going On” (Marvin Gaye, 1971), “Papa was a Rollin’ Stone” (The Temptations, 1972), “Come a Little Closer” (Etta James, 1974), “Car Wash” (Rose Royce, 1976), and “I Will Survive” (Gloria Gaynor, 1978).

Death and Rebirth

With the 1980s came an era of new wave and punk rock music. Gradually, rock music fell out of vogue, and was replaced by the new technology of a digital revolution: musicians favored synthesizers over guitars, and effects processors over natural acoustics.

Progress in computer chip integration led to the creation of hundreds of digital guitar pedals, and the wah — a simple, unsophisticated, electromechanical pedal — was used less and less.

Thomas Organ also began to come under question for its quality control. In building its wah pedals, the company would “grab whatever [components] that were available from any manufacturer and put them together.” These inconsistencies (largely with the inductor type, which gave the wah its characteristic tone), paired with the pedal’s waning popularity, led Thomas Organ to question its value.

In 1982, Whirlpool, the conglomerate that owned Thomas Organ, decided to shut down the company, and cease production of the wah pedal.

One man, Jim Dunlop, decided he couldn’t stand for this to happen.

Jim Dunlop at the Scottish music awards in 2011; via Dunlop

A Scottish immigrant, Dunlop had founded Dunlop Manufacturing, a guitar accessories company, in 1965 while working part-time as a chemical engineer. After a few early successes redesigning guitar tuners and capos, he moved onto guitar picks, and eventually took over that market space. “He was known as a collector of accessories,” his daughter stated in an interview. “If people had accessories that they couldn’t make, they’d take to Jim Dunlop, and he’d make them.”

In 1982, during Thomas Organ’s liquidation, Dunlop called a VP at Whirlpool and offered to buy the rights to the pedal; the VP, who had no interest in the music business, gladly handed it over. Dunlop then spent 9 months remodeling the pedal: the circuit was rebuilt, the pots were replaced and updated, and it was built to be more durable.

After guitarist Stevie Ray Vaughan recorded a remake of Jimi Hendrix’s “Voodoo Child” in 1984, the pedal gradually came back into heavy use, and was prominently featured by bands like Guns N’ Roses, Metallica, and Toto.

This revival continued through the grunge movement in the 1990s: Nirvana, Alice in Chains, and Pearl Jam championed the pedal’s use, and most big-name guitar players reinstated it into their effect rig.

***

Today, despite the increasing digitalization of popular music, the wah pedal is just as prevalent as it’s ever been. In 2008, for instance, Jimi Hendrix’s old wah pedal sold for $15,500 at an auction, and its owner was immediately inundated by popular artists with requests to borrow it.

Though it has since been usurped by “sexier” effects and computer sound banks that can replicate any sound, the wah has managed to retain its place in music history.

“[The wah] is a dynamic thing, and every moment is new,” says Bobby Cedro, an engineer at Dunlop. “You can never replicate, perfectly, a wah-wah passage. That’s what makes it organic, and that’s what makes it timeless.”

![]()

Our next post explores the 19th century version of Drake vs Meek Mill: a fight between two mathematicians who both claimed to have invented statistical regression.

To get notified when we post it → join our email list.

![]()

This post was written by Zachary Crockett. You can follow him on Twitter at @zzcrockett