“I am an observer of life, a non-participant who takes no sides. I am in the regimented society, but not of it.”

— Moondog, 1964

![]()

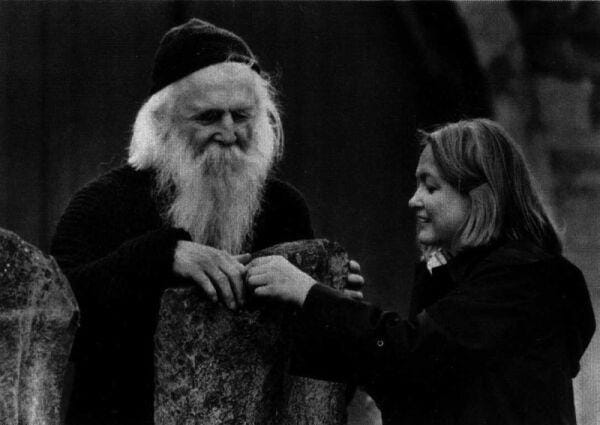

For thirty years, a lumbering, blind “Viking” roamed the streets of New York City.

Armed with a six-foot, steel-pointed spear, a horned, leather-embossed cap, and a long, wispy beard, he’d find a spot along Sixth Avenue, set up his array of homemade instruments, and stand placidly for eight hours, like some ancient humanized statue. Amidst the shrill horns, screeching tires, and tumbling foot traffic of Manhattan, the sightless giant would gently rap on his drum, advertising his wares — a set of albums and hand-written poems — to anyone interested.

To the whole of the public, he was nothing more than a nutty, homeless waif. But unbeknownst to them, the Viking — known more formally as Louis Hardin, Jr., or ‘Moondog’ — had record deals, had been covered by Janis Joplin, and had been endorsed by some of the world’s greatest composers.

Moondog’s legacy is that of a man who endured through tumultuous circumstances — acquired blindness, homelessness, and prejudice — to become who many would call one of the most talented and under-appreciated musicians of the 20th century.

Moonpuppy

On May 26, 1916, in the backwoods of Marysville, Kansas, a healthy baby named Louis Thomas Hardin, Jr. was born. From a young age, Hardin’s parents, an Episcopal preacher and an accompanying organist, encouraged exposure to the arts: he was read everything from the satirical musings of Mark Twain to the King James Bible. His parents also imparted on him an affection for music — particularly percussion. By the age of 5, Hardin had fashioned a set of drums from cardboard boxes; his father, sensing the child’s fascination, would take him to Arapaho Sun Dances, where he’d bang on buffalo-skin tom-toms and receive impromptu lessons from Native Americans.

His folks’ work life was itinerant, and the family often moved around. By the time Hardin was ten, he’d shuffled through Wisconsin, Wyoming, and Missouri, often at the whim of his father, who held various jobs as a “merchant, rancher, and insurance agent” after falling out of grace as a minister. Through this odyssey, Hardin accumulated a visionary collage of experiences — until tragedy struck.

Toward the tail end of his time in Missouri, on the 4th of July, Hardin, then 16, came across a curious, cylindrical object out in the fields and began to toss it around. Hardin’s momentary curiosity would change the course of his life: the object, a dynamite cap, exploded in his face, and he was permanently blinded.

In the years following his accident, Hardin encountered a number of struggles — chiefly, learning Braille, adjusting to a life without eyesight, and coping with the ugly divorce of his parents. During this time, Hardin’s older sister, Ruth, emerged as his mentor, reading him a wide array of philosophical, scientific, and mythological works; in time, he entirely abandoned his family’s Christian faith. As he learned to take solace in auditory sensations, Hardin’s early love for music returned with burning ambition: he vowed to devote himself entirely to composition.

At Iowa’s School for the Blind, he made good use of his time, familiarizing himself with a number of instruments, as well as composition theory and ear training. He went on to continue his studies in Memphis, Tennessee, where he met and married a “socially prominent” elderly woman, who convinced a wealthy friend to fund Hardin’s musical pursuits. Less than six months later, the relationship fell apart, and Hardin found himself without funds, and isolated from his peers.

Alone, poor, and with the grandiose dream of becoming a composer, Hardin packed his belongings and ventured to New York City.

Homeless in New York

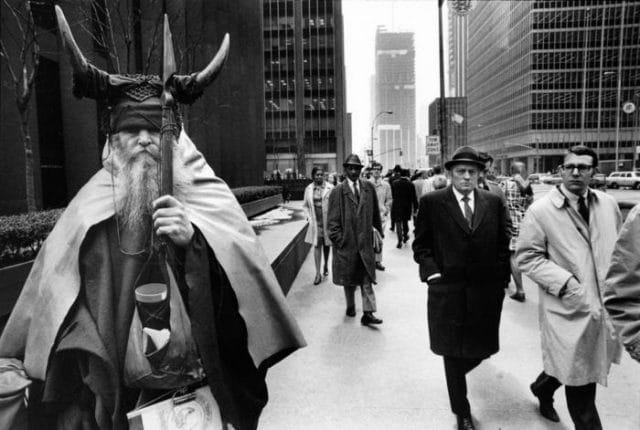

Moondog on the streets of New York, c.1953

In 1947, at age 27, Hardin arrived in big city with no contacts, no prospect of work, and little more than a month’s rent. Though he’d learned to sense his surroundings as a blind man, the crowded streets and bustling sidewalks of Manhattan quickly proved to be overwhelming.

Unsure of where to turn for guidance, Hardin decided to set himself up where he knew there’d be musicians about: on the sidewalk just outside of the stage entrance to Carnegie Hall, New York’s preeminent stomping grounds for composers. At well over six feet tall, and with chiseled features, Hardin was a striking figure, nonetheless immensely talented — and after weeks sitting out front with his drum, people began to take notice. In time, he struck up conversations with various New York Philharmonic musicians, who then insisted that he meet Artur Rodzinski and Arturo Toscanini, both established conductors. Rodzinski was instantly impressed by Hardin, and offered him a deal: if Hardin could produce a favorable composition, Rodzinski would allow him to conduct it at the Philharmonic — but he’d have to produce it himself.

Without the funds necessary to pay an assistant to translate his music, Hardin returned to the streets to perform. For a number of years, he remained here, homeless, bearded, and destitute, playing for coins and working on his compositions. And then, slowly, he began to transform.

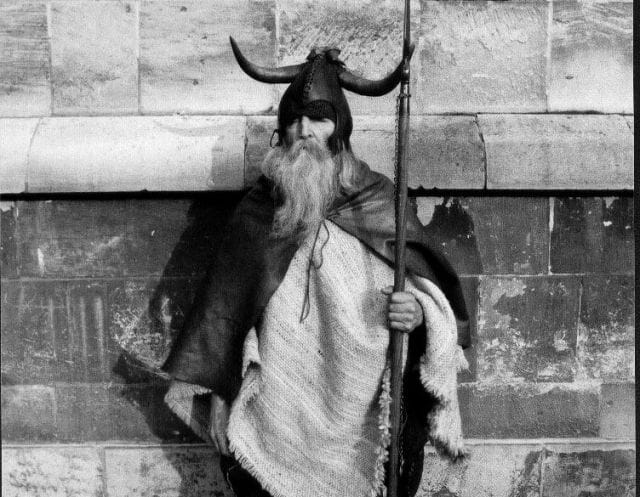

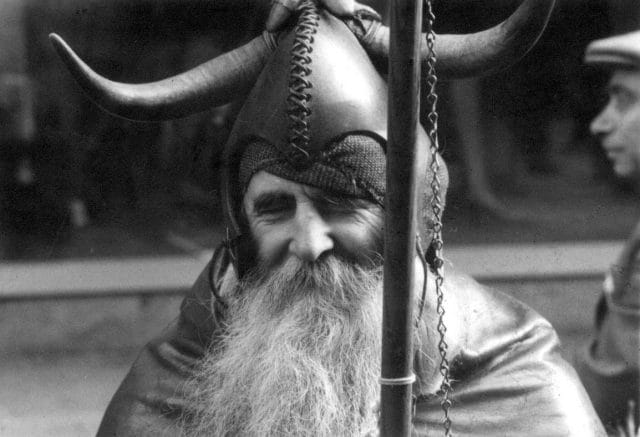

After repeated comments from passersby that he looked like Jesus Christ, the anti-Christian Hardin grew weary. “I put up with that for a few years, getting compared with a monk or Christ,” he later recalled in an interview. “Then I said, ‘That’s enough, I don’t want that connection. I must do something about my appearance to make it look un-Christian.’” At the time, Hardin was intensely interested in Nordic mythology, so he decided he’d alter his appearance to show his devotion.

It began with a series a reddish-brown robes and a flowing dark beard — a get-up that Hardin quickly found to be inadequate. Soon, he’d adopted a full Viking-esque regalia: a horned helmet (his symbol of “virility”), a long, tapered spear (his symbol of “freedom”), self-crafted leather boots, and a flowing, bulky ensemble of blankets, cloths, and capes.

In 1947, Hardin began calling himself ‘Moondog’ — an homage to a childhood pet dog who’d “bayed at the moon” — and encouraged others to identify him by the moniker. As Moondog got increasingly stranger, both in philosophy and fashion, he began to fall out of favor with the musicians who’d previously endorsed him.

”I had a lot of offers from people who said that they would help me but that I had to dress conventionally,” he’d later say, ”but I valued my freedom of dress more than I cared to advance my career as a composer. I just wanted to do my own thing, and no matter how much it cost me in terms of my career, I did it.”

Hardin applied the same non-conformist philosophy to his music; striving for new, unique ways to do things, he began to construct his own instruments with the help of a local cabinet-maker. These included the “uni,” a seven-stringed zither; the “utsu,” a rudimentary type of keyboard tuned to the pentatonic scale (the same intervals of the black keys on a piano); the “tjui,” a series of nine tuned wooden pegs, and the “oo,” a triangular 25-stringed harp, which he favored most passionately.

Living on the street, he drew inspiration from the various sounds the surrounded him — fog horns, street cars, footsteps, echoes, sirens — and also learned to appreciate the importance of silence in composition. Pairing these influences with his early inspiration from Native American rhythms, Moondog released his first record, “Moondog’s Symphony,” in 1949. Using what he called “snake rhythm” (a slithery, complex beat that was a far departure from popular music at the time), Moondog’s creation was unlike anything ever produced:

‘Moondog’s Symphony’ (1949)

He took to selling his music, along with his hand-written poetry (usually, verses written in rhymed heptameter couplets), on the Avenue of the Americas, in the heart of Manhattan. At times, his antics would arouse the wrong sort of attention: in November of 1950, he was arrested for soliciting passersby with his music, and for enlisting the help of a 10-year-old boy to hand out fliers advertising his new work.

Moondog’s persistence paid off, and he began to slowly gain traction as not only as one of New York’s premier eccentrics, but as a laudable musician. One day, while sitting on the street plucking at his home-made instruments, he was offered the chance to produce some singles; this led to an opportunity to produce a full album — a collection of “eight odd, exotic-sounding tunes” called “Moondog on the streets of New York” — which earned a review from theTimes:

“Moondog in person is as bizarre and the music he plays. He wears a nondescript brown robe and sandals, a flowing beard and uncut hair in two braids over his shoulders. When performing, he places his instruments on the sidewalk and squats before them like a street musician in some Oriental bazaar. When asked, he tells questioners he’s from ‘Sasnak’ (Kansas backwards).”

Around this time, Moondog also met his muse, an elderly Japanese woman named Mary Suzuko Whiteing, who assisted him in cataloguing his compositions, many of which fit on a single page, due to the expensive process of transcribing Braille to musical notation. With his work in hand, Moondog was able to start landing shows at small venues around the city — but not before fighting for the rights to his name.

Moondog Vs. the “Father of Rock n’ Roll”

MOONDOG in Münster 1975/Photograph : Norbert Nowotsch

In the early 1950s, a young Cleveland disc jockey named Alan Freed got his hands on a copy of “Moondog Symphony,” and was instantly obsessed with it. He began calling his show “The Moondog House,” touted himself as “The King of the Moondoggers,” and used Moondog’s album as his show’s theme song, without permission. By 1952, the concept had became a phenomenon: a concert, dubbed “The Moondog Coronation Ball,” was organized at Cleveland Arena, and attracted a crowd so large and riotous that it had to be shut down (this was later cited as America’s “first rock ‘n roll show”). Advertisers subsequently recognized the program’s potential, and syndicated it in New York.

When Moondog’s fans heard the program, they immediately recognized that Freed had capitalized on the musician’s talent, and urged him to take action. So, in 1954, Moondog — the bearded, homeless, Merlin-look-alike — took on radio’s hottest DJ in court, filing an injunction against him. Despite the fact that Moondog’s works were not copyrighted, he was awarded $6,000 in personal damages, and Freed was forced to discontinue the use of “Moondog” — largely thanks to the fact that prominent swing musician Benny Goodman had come to Moondog’s defense.

Alternately, Freed would go on to term his show “rock and roll,” coining the phrase.

***

After moving into a shabby midtown hotel room and focusing on his work, Moondog gained a cult following among some of New York’s finest musicians. Throughout the 1950s, he played profusely both on the streets, and in underground venues — often far past midnight.

One show in 1955 billed him with Kenny Graham, “one of Britain’s foremost jazz composers and arrangers,” and was touted by the New York Times as “throbbing, percussive, [and] hypnotic.” Wrote the reviewer, “The bearded maverick strikes the drum with clavas or maracas as an Indian bell-bracelet rings gently from his wrist: it is an enchanting sound distinctive to Moondog.”

With the arrival of beatniks and hippies in the 1960s, appreciation for Moondog’s strange, non-conformist music grew exponentially: in New york, and beyond, he became an icon of the absurd.

Up-and-coming jazz legends Charlie Parker and Charles Mingus touted him as an innovator; minimalist composers Philip Glass and Steve Reich took his work “very seriously,” and recorded works with him. Famed rocker Janis Joplin recorded a cover of his song, “All Is Loneliness,” and introduced Moondog to a new generation of 60s hipsters. He shared the stage with the likes of painter Salvador Dali, poets William Burroughs and Allen Ginsberg, and renowned sitar player Ravi Shankar. In 1969, CBS records backed him with a full orchestra, and released ‘Moondog,’ a compilation of his compositions; two years later, they released ‘Moondog 2.’

Moondog’s Lament I, ‘Bird’s Lament’ (1969)

Moondog was such a fixture on the streets of New York that when textile manufacturer Burlington Industries brought a new exhibition to the city in 1969, they listed him an a landmark. “You may find us,” wrote the company in an advertisement, “up the street from Radio City, down the street from Central Park, and across the street from Moondog.” City dwellers knew exactly where to go.

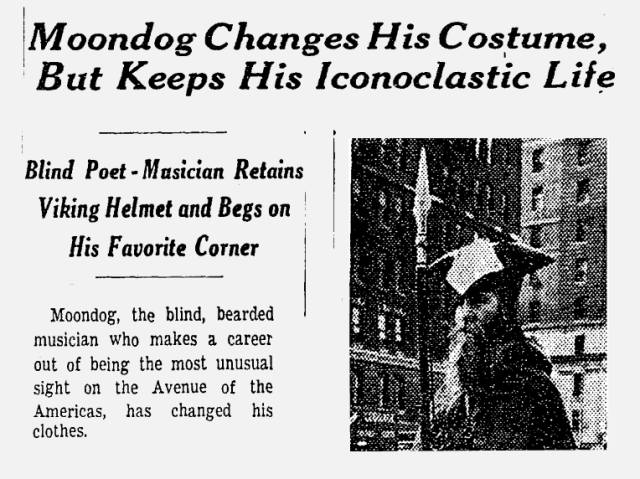

Despite all of this, Moondog continued to inconspicuously play on the streets, to relatively little fanfare. He took no great satisfaction in fame or recognition, and only sought to improve his own craft. The whole of society continued to know very little about him, and most who passed him on the sidewalk thought he was either a “loony,” or a drug addict.

“Although he is a serious musician with several recordings to his credit, he makes his living begging,” reported the Times in 1965, when Moondog’s slight wardrobe modifications drew a headline. “He drinks from a hollow moose’s hoof…and [wears] a velvet cloak and hood of brilliant scarlet, lined with pale green satin,” the paper continued, “and stands for 8 hours a day on midtown corner.”

When asked whether he was ashamed about begging, Moondog’s response was candid — “It’s not degrading. Homer begged, and so did Jesus Christ. It was only the Calvinists who ordained that no man shall eat who does not work” — and he made sure to clarify that the only gods he held in regard were “the Gods of the viking pantheon, like Thor and Odin.”

While he remained fairly underground, his antics never failed to drawn large crowds on the street. By 1965, he’d became such a spectacle that the police ordered him to cease his performances; he often rotated from location to location to avoid law enforcement. After all, it was here, on the street, that he was happiest.

“You don’t get exhaust fumes here because there’s an air shaft,” he told a reporter, “and the pigeons cooing and flapping above are my little bit of nature.”

Often, he’d be taunted for his attire, but he refused to change his ways. “It’s my way of saying ‘no’,” he’d say. “[People] try to chip away at you, to make you a conventional stereotype, and I have no interest in being conventional.” Ironically, this stance won him praise from fashionistas. “Moondog is an original,” fashion pioneer Bonnie Cashin told a room full of designers in 1970. “We are the phonies.”

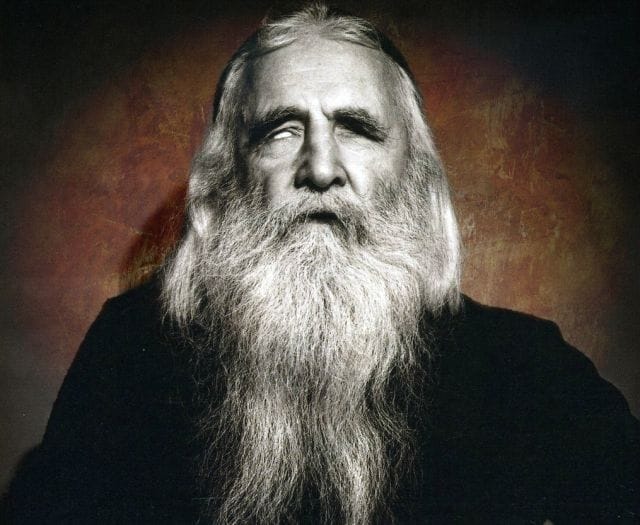

Moondog, in his later years (c.late 1960s)

Above all, Moondog remained curious, and eager to learn from sources of inspiration that often went neglected. “Moondog could work lyrically with odd rhythms,” recalls Philip Glass, with whom Moondog lived for nearly a year in the late 1960s:

“He’d stand in the stairway to the jazz club Birdland and play along with anything they were playing inside the club. I was amazed at his facility for doing this, and the way he could make music of found sounds. I remember him standing on the roof overlooking the Hudson River, and when the Queen Elizabeth pulled into port, blowing its horn, Moondog would toot along with it on his bamboo flute.”

Eventually, it was this very curiosity that led to Moondog’s exit from New York.

Moondog Finds a Family

When Hessische Rundfunk, a prominent German radio station, offered Moondog the opportunity to play a set of shows abroad in 1974, he was delighted. After spending more than three decades establishing himself in New York, he was ready for a change, and eager to experience the “homeland of his musical idols.” Moondog’s absence from the city’s streets was so unusual that New York’s commuters and shop owners wrote to the Times inquiring if he’d died. But he hadn’t — he’d simply disappeared abroad.

For two years, he roamed Europe, more or less doing what he’d done in America: peddling his music and poetry on the streets. Then in 1976, while on a street corner in the small town of Recklinghausen, dressed in full Viking regalia, he caught the eye of a 24-year-old German girl named Ilona Sommer.

“My 10-year-old brother wanted to invite him home for Christmas because he felt so sorry for him,” she recalled to a reporter in 1979, “but no one in the family had the nerve to ask him.” Then, she heard his music:

“I saw the record of his music — orchestra pieces played by 45 musicians…and I bought it. When I first heard the music, I was shaken! I couldn’t believe that a man who could write music like that would have to live as he did. So then I invited him home.”

With Sommer’s father’s endorsement, Moondog soon moved into the family’s home in Oer-Erkenschwick, an “uninspiring little town in West Germany.” Soon, Sommer quit her archaeology studies and became Moondog’s full-time “publisher, producer, agent, and transcriber.”

Over the ensuing three years, she negotiated the release two new albums of Moondog’s music., which she released through her own independent publishing company, Managram; she’d also secure a deal with another producer, Roof, to fund two new Moondog albums per year. By all accounts, she rejuvenated the man’s career, and made him something of a European sensation.

And in this new environment, Moondog flourished.

“I am living in a composer’s paradise,” he told a reporter, shortly after moving in with Sommer. “I am surrounded by musicians, I get my meals on time, I’m warm, and most of all I’m free for my music.” With this freedom, he produced a prolific amount of work — and also some of his finest (ie. “Sax Pax,” and “Big Band”) — and embarked on frequent tours around Britain, Austria, France. He even once conducted his avant-garde music before the Royal Court.

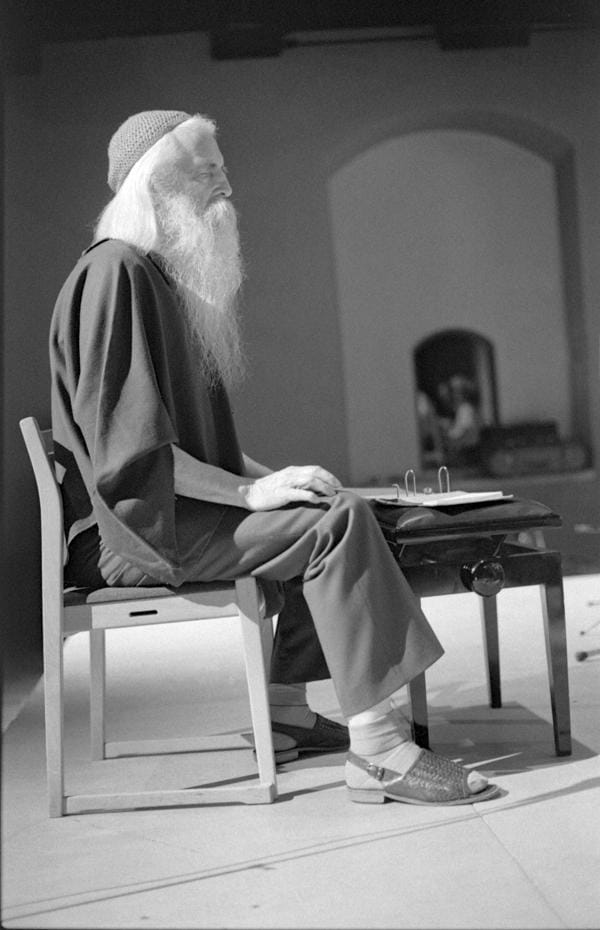

Under Sommer’s direction, Moondog also compromised a few of his eccentricities: his horned Viking hat was traded in for a hand-knit beanie, his shall for a sweater, and his satin robe for “fashionable jersey pants.” The majestic white beard and flowing mane of hair, however, remained.

Moondog, composing in his new threads

”The persuasion of a woman is unbeatable,” he’d later concede. ”But I still love horned helmets, and swords, and spears. I like to feel that I’m loyal to my past. I wouldn’t want to be on the street anymore. But you know, [ being on the street] led to a lot of things.”

Often, Moondog lamented being away from the streets on which he first gained a reputation. “New York City was my mother and father for 30 years,” he recalled in the late 70s. “I worked and slept on her streets and ate through the kind generosity of her people. I would like to go back someday — most of all I would like to have a concert of my music there.”

Moondog’s wish to return eventually came to fruition — and in grand form.

In 1989, after 15 years away from New York, Brooklyn’s Philharmonic Chamber Orchestra invited him back to conduct a 30-minute performance of his own works. The homeless Viking who’d once been dismissed from Carnegie Hall for his eccentricity was now standing before hundreds a well-dressed denizens, leading a group of Juilliard-trained musicians who were playing his own music.

As recalled in a 1989 review of the performance, Moondog seemed bashful about being in charge:

“Like much else about him, Moondog’s conducting style is unusual. He is uncomfortable with being an authority figure, so he sits to the side of the orchestra and provides the beat on a bass drum or timpani. Speaking of the orchestra members during an interview in his East Side hotel room the other day, he said: ‘I see my relationship with them as being first among equals, so that in a way there are 40 conductors, each in charge of his own part, and each responsible for the performance.’”

Despite glowing reviews, the show would be Moondog’s last in the United States. As quickly as he’d reappeared, the “Viking of Sixth Avenue” absconded back to West Germany.

He’d never return.

Hippie Hero

On September 8, 1999, at the age of 83, Louis ‘Moondog’ Hardin passed away in Munster, Germany, presumably from heart failure.

In his time, Moondog had influenced hundreds of artists, including some of the greatest musicians of the 20th century — Philip Glass, Charlie Parker, Charles Mingus, and Janis Joplin among them. Today everyone from rock band Mars Volta to trip-hop group Portishead cites him as a source of inspiration.

He’d willed himself through the harsh streets of New York, found ways to dazzle onlookers, and signed record deals as a homeless man — all the while pridefully defending his eccentricities. And after all of this, he’d redefined himself abroad — had come to life more brilliantly than ever before, in unfamiliar territory.

His legacy has since been cemented in books, New York ice cream parlors, and, most recently, a documentary film that raised more than $100,000 on Kickstarter.

”He led an extraordinary life for a blind man who came to New York with no contacts and a month’s rent, and who lived on the streets of New York for 30 years,” said Dr. Robert Scotto, a New York-based English professor who published a biography on Moondog’s life shortly after his passing. ”Without question, he was the most famous street person of his time, a hero to a generation of hippies and flower children.”

![]()

This post was written by Zachary Crockett. You can follow him on Twitter here.

To get occasional notifications when we write blog posts, please sign up for our email list.