“Every time I see an adult on a bicycle, I no longer despair for

the future of the human race.”

~ H.G. Wells

As far back as Brent Curry can remember, he was a tinkerer. In the suburbs of Waterloo, Ontario, he spent his early years taking things apart and reassembling them.

By the time he was 15 years old, he’d taken up an intense interest in cycling, and began building his own bikes. “From then on,” he says, “I knew I wanted to get into the bicycle industry.” Eventually, he continued on to the University of Waterloo, where he studied mechanical engineering and spent his summers interning with prestigious bike companies around the world:

“I started with Vitus in France. They made a point there of moving the intern around a whole bunch of different divisions of the company, which was great for me, because it exposed me to all aspects of the bike building process — things like R&D, frame design, stability testing. After that, I built mail delivery bikes in Australia, and worked with Dekerf Cycles in Vancouver.”

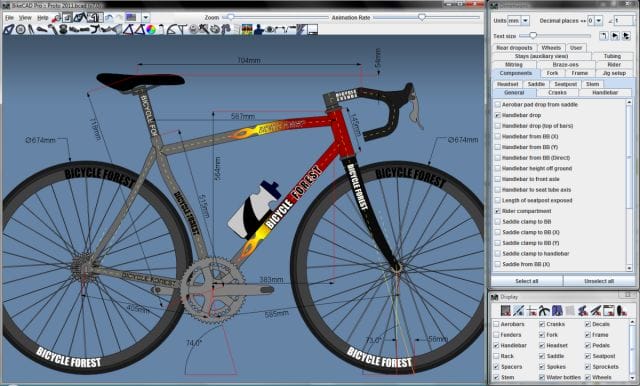

During these internships, Curry spent a lot of time “preparing technical drawings of bikes” using the design and drafting program AutoCAD. But he realized that the program had limitations as a bike frame building tool. “I realized it was frustrating to work with a non-parametric design tool when you’re dealing with bikes,” he recalls. “If you wanted to make one of the bike tubes longer or whatever, you had to re-gut the whole thing.”

At the time (mid-1990s), “parametric” design programs — or those that allow the user to input parameters, then scale and/or tweak them — were just emerging. So, armed with a limited knowledge of computer programing and a huge spreadsheet of the lengths and angles of various diamond frame bike tubes, Curry decided to build his own parametric design tool specific to bicycles. He called it BikeCAD.

Shortly after he finished the first “crude” draft of the program, he created a website, The Bicycle Forest, and made it available to use for free, so that aspiring frame builders could realize their visions. But Curry had a more pressing motive for making BikeCAD: “I mainly built the program so I could design my own bikes.”

He knew he didn’t want to build “conventional” diamond-frame bikes. “Chris Dekerf, who I’d worked under, was such a master builder, that I felt like I’d never actually achieve his level of skill,” he says. “So I didn’t want to compete in that area.”

Instead, he set out on a crusade to build “the most unusual bike possible” to take on a tour.

“I had done a lot of bike touring in the past, but my objective had always been to do the hardest trip possible [things like an unsupported tour through the Canadian Arctic],” he says. “For once, I wanted to do something where the focus was having a good time.”

Hence, the “Couchbike” was born.

***

It began with a couch — an old, 95-pound leatherette loveseat, to be precise. A college buddy had left it lying around at Curry’s place and forgotten about it; now, as Curry sat in its plush cushions racking his brain for unique bike designs, he figured, “Why not build a bike out of this thing?”

When his old high school friend, Eivind, whom he hadn’t seen in ten years, reached out from Norway and informed him he’d be coming out for a visit, Curry told him about his new idea, and the two agreed they’d take the Couchbike on a tour. Curry had the incentive he needed to get cracking.

The next day, he went out and procured a “massive heap of steel tubing and aluminum billet.” Then, over the course of three months, he designed a custom frame to fit the dimensions of the couch, cut out the tubes to length, and welded them into form. At this point, Curry was highly dubious of his experimental project:

“I had no idea whether [my work] would yield the most fantastic touring bicycle known to man, or a feckless monstrosity I’d need to borrow a farmer’s tractor to drag off my property.”

The bike was barely finished when Eivind arrived, and no time could be spared in taking it for a test ride before their tour. “We got the thing assembled and pedaled it around the block to the grocery store,” says Curry. “That was enough confirmation for us to hit the road.”

Their plan was ambitious: they’d start in New Brunswick, and snake along the coast, across Confederation Bridge, into Prince Edward Island — all the while traveling on a combination of dirt and gravel roads. In total, the trip would be about 500 kilometers (310 miles).

The two sat side-by-side on the couch, legs raised forward to spin the pedals, writes Curry:

“The Couchbike was steered with a tiller, which was linked to the two front wheels on each side of the couch….It had two independent drive trains, each with 144 different gear combinations, and the gear ratios were disproportionately skewed in the high range. While our high gear was more than double that of a standard mountain bike, our low gear was only 7% lower than normal. So we struggled and sometimes had to push up the hills.”

Though the bicycle’s pace for the duration of the trip was generally that of a “brisk walk,” the duo, at one point, achieved a max speed of 44 km/hr (27 mph). “That was terrifying,” recalls Curry, “and was definitely faster than I wanted to be going.”

In the end, despite a few hiccups, Curry’s Couchbike tour was a success, and inspired him to continue his pursuit of strange bicycle designs.

***

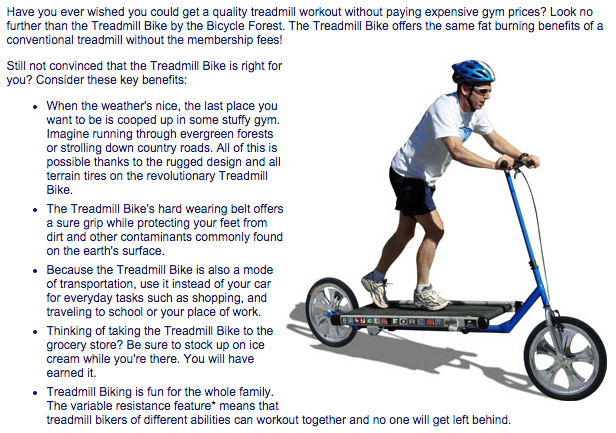

The “Treadmill Bike” began as a lighthearted joke to “poke fun at people who drive their cars to the gym to run on a treadmill.”

Its physics are simple and creative: the rider runs on a mini treadmill mounted to a custom-built frame; when set into motion, the treadmill, which is “butted up” against the rear wheel, propels the bike forward. With his invention completed, Curry posted a “mock advertisement” of the bike in action to YouTube:

Additionally, on his website, he posted a “list of benefits” that one would receive by using his device as a primary source of exercise:

Though the bike was clearly made in jest, hundreds of people took it seriously. As the YouTube video spread, Curry began getting interview requests from television, radio, and newspapers outlets all across the world. “It had multiple appearances on TV shows,” says Curry. “Japan, Germany, Britain, the U.S. — it was all over the place.”

Famous game show The Price Is Right even requested that the Treadmill Bike be used as a prize on its show. Luckily, the contestant narrowly missed guessing its correct retail price ($2,500), and Curry got it back. He went on to produce a second one and sell it to a Japanese television show, where it was fitted with training wheels. “They dressed up a chimpanzee in overalls and had him ride it,” Curry later told Slow Twitch. “I’m not making this up.”

Over the ensuing years, Curry has engineered a handful of other “wacky” bicycles.

His curiously-named “Hulabike” enlists “an eccentrically laced rear wheel” in lieu of the traditional drivetrain. “Because the hub is offset from the centre of the rim, the bike can be propelled by hopping up and down with the right rhythm,” he writes on his site. “You may not get far on the HulaBike, but you’ll have fun trying.”

When Curry felt the need to “win customer support through vehicular intimidation,” he purchased a Rhoades Car (a 4-wheeled bicycle that drives like a car), then proceeded to weld together a steel frame around it “in the style of a pickup truck,” paint it “John Deere yellow,” and fit it with head lights, tail lights, a plexiglass windshield, and a set of flashy, aftermarket rims.

Along with this bike came a new company motto: “We’re the Bicycle Forest, and nobody messes with us!”

***

While creating odd-ball bikes began as Curry’s hobby, it eventually turned into a full-time business — though not in the way he expected it to.

In 2004, New York-based cycling company Serotta came across the free, somewhat-jenky version of BikeCAD he’d posted on his website six years earlier, and expressed interest in customizing it for their own use.

“I agreed to do some work for them,” he says, “and in the process, I realized there was a huge potential for further developing BikeCAD.”

In his free time, he created a second, heavily vamped-up version of the program that included a multitude of new features including the ability to visualize a rider and fit him to a custom bike, total and complete customization down to the paint scheme, and an option to export designs in printable CSV and PDF files. While continuing to give access to his original program for free, Curry offered his new, updated version for a one-time fee of $350 CAD ($270 USD), and called it BikeCAD PRO:

Since releasing the program, framebuilders, specialists, and bike shop owners have shown a great interest in the robust software. Curry says that over the last six years alone, he’s sold roughly 1,500 copies — enough to make this his full-time job. And like his penchant for fashioning strange bicycles, BikeCAD PRO is constantly evolving.

“I constantly get tons of feedback from the cycling and framebuilding communities,” he says. “They’re passionate, supportive people.”

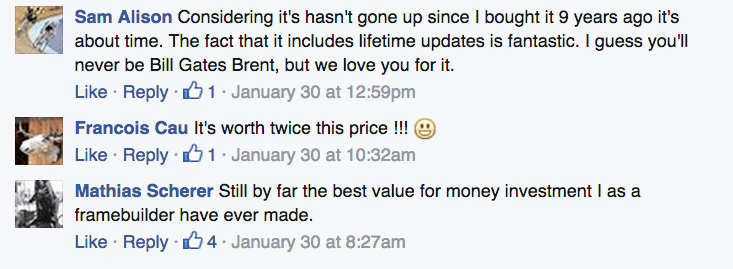

Despite its success, Curry refused to raised the program’s price. Last month, after nearly 10 years of charging $350, he finally ceded. “I saw no need to raise it in all those years, but recently, the Canadian dollar has really taken a beating,” he admits. “that prompted me to raise to price, for the first time ever, to $500 CAD.” When he broke the news to his supporters on BikeCAD’s Facebook page, they rallied around him in support:

On Curry’s website, he’s garnered the support of another community: hundreds of amateur bike builders email him photos of their strange, home-made contraptions, which he then posts on his blog. What’s more, in a roundabout way, Curry’s wacky bicycle building obsession has turned into a side business. On his site, he’s more than happy to entertain offers to rent out his homemade cycles — Couchbike included.

“If someone’s willing to come out here, I’ll rent it for $50 a day,” he says. “If you need me to cart it somewhere, it’ll be a bit more…it’s a very awkward bike to transport.”

This post was written by Zachary Crockett. You can follow him on Twitter here.

To get occasional notifications when we write blog posts, please sign up for our email list.