There is no Trader Joe’s in Canada.

Imagine — maybe you don’t have to — you’re Canadian. You’re at a dinner party, and the host has put out a bowl of the best snack you’ve ever had. Love at first bite, and it’s going fast. Soon enough, your fingers graze the bottom of the bowl and you realize that the end is nigh. You master your panic.

“Host,” you chime. “Who makes these chocolate caramel peanut butter mango pretzel chip things?” You wait with bated breath and weird, crumb-covered lips.

“Trader Joes,” he replies, and your heart shatters. This dinner party is in Vancouver. A trip to the nearest Trader Joe’s in Bellingham, Washington costs hours in travel, and in line waits both at the border and in the crowded store. Just thinking about it causes the snack, once so sweet and savory, to turn acrid on your tongue.

Your host notices your grimace and chuckles. “Chill dude,” he says, with smiling eyes. “I bought these in Vancouver. You can too.”

Your mind wrestles with the information, “There’s a Trader Joe’s in Vancouver, now?”

“No, there’s a Pirate Joe’s in Vancouver.”

What unfolds then is a tale of entrepreneurship, adventure, legal turmoil, and something called “the grey market.”

A Pirate’s Life

Meet Michael Hallatt, itinerant adventurer and a man of many trades. Lithe and grey-eyed, kind and intense, he speaks quickly — leaping from story to joke to political opinion and onto the next revolution, woebetide those who can’t keep up. He’s been a designer, a baker, a programmer, a carpenter, a filmmaker and – for the past two and a half years — a “pirate” importing Trader Joe’s foods across the US/Canadian border.

Hallatt first developed his taste for Trader Joe’s back in 2000. He had been working for AskJeeves and living in Mill Valley – a “food snob” town in the San Francisco suburbs, and not quite Trader Joe’s territory. But when the Internet Bubble burst, he got out of software and bought a fixer-upper house in blue-collar Emeryville.

“I was living on the construction site and pinching pennies,” he tells us. “I’d go to the nearby Trader Joe’s and fill up a shopping cart with frozen tamales and enchiladas. I lived off of that.”

When the dot-com bubble burst, Hallatt put his money into a fixer-upper in Emeryville

“I ended up falling in love with someone, and our daughter was basically conceived on tamales.” His partner was from Vancouver, so they eventually ended up leaving the house Hallat built – now called “the Buddhahouse” — and moving back to his native Canada.

The fixer-upper fixed up, now called ‘The Buddhahouse’

“All of a sudden my life was in a place where I needed a day job,” Hallatt said. “I knew that probably meant being a middle manager at a software place, and I’d done that already.

“Or,” he suggested, “I had to start something!” He found himself reminiscing for his career pre-software, and the bagelery he dropped out of design school to open in the 1980’s. He also found himself “jonesing for some TJ’s,” so he made the trek to Bellingham.

“The place was full of Canadians,” Hallatt said, “and I’m a bit of a stranger talker.” A big topic of conversation in the checkout line was why the Canadians had to come all this way to get their Trader Joe’s fix. Somebody mentioned a lady in Point Roberts (a US city that is contiguous with mainland Canada), had set up a home delivery service that stocked a few private label items, which got Hallatt thinking.

By the time he got to the register, Hallatt had conceived Pirate Joe’s. He would start buying large quantities of Trader Joe’s products in the US and importing them to Canada. Large quantities — enough to stock a physical store. He’d make regular border runs to keep the inventory fresh, and mark up the products to cover rent and operations. Voila! Canadians would get their Trader Joe’s products without the trek, Trader Joe’s would get a “presence” in Canada without the legal hassle, and Hallatt would get a pretty funky “day job” where he was the boss.

One of Hallatt’s shopper’s living rooms, after a day on the job

That trip was also when he met “Kyle”, who said he was the manager of the Bellingham store. Kyle would help him out, because supplying Hallatt would be a huge boon for the Bellingham store’s sales.

“It took us six months to figure the whole thing out,” Hallatt said.

For one thing, he decided he needed a storefront. He bought a Romanian Bakery, and fixed up the roof and left up the sign. “It was clunky, he said, but a great find on the outside. It looked like the funkiest coolest weirdo from another age,” he said. “Who was I to tear it down? It was a tribute to the soul of the place.” ‘Transylvania Peasant Bread’ became ‘Transylvania Trading Company’ – which was to be his store’s first front.

It was important to Hallatt to import his stock legally. Because of NAFTA, Hallatt was able to get most of his goods North duty-free, but he had so much to declare that he wrote a program to generate a barcode to summarize his haul. “Of course, the system broke right away,” Hallatt said. The barcode wouldn’t scan. “I was stuck at the border, with a trailer, in the winter, on a shoestring.”

In order to sell the items in Canada, he also had to print out new nutrition labels for each of them that met Canadian regulations. He devised a system, then drove to Bellingham and bought one of everything to test it. “The cashiers co-operated. They knew what I was doing so it was an easy checkout — instead of going through the cart they just charged me for one of everything.”

Hallatt took a lot more trips to Bellingham in those six months. Every time, Kyle would be at the store, waiting for him and egging him on.

“At some point I asked, ‘Well what if corporate finds out?’” Hallatt said. “And Kyle said, ‘They’re too stoned to find out.’”

Kyle, it turned out, was the junior manager of the store, not the head honcho running the location. Hallatt discovered this the hard way.

The first full haul was seamless, and the Transylvania Trading Company successfully opened its doors on January 1, 2012. They got a slow trickle of confused customers — some of whom were very quickly enthused once they discovered what the store had to offer. But the second haul, Kyle’ boss – the Bellingham senior manager – came out to ask a few questions. The senior manager called corporate for guidance, which is how, his second week in business, Hallatt was banned from his first Trader Joe’s.

“So I just started buying stuff out of Seattle,” he said, nonchalantly. “There’s more stores and more selection there, anyways.”

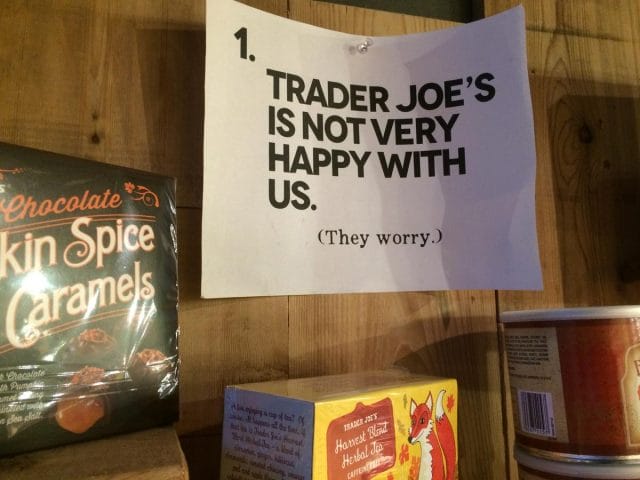

A sign at the checkout at Pirate Joe’s

Trader Joe’s sent Hallatt a cease and desist letter; he put it up in the window and went on with business. From then on, things proceded pretty quietly for a while. Pricing took some time to figure out (today, it’s still not an exact science: Hallatt marks up the “luxury” items more to subsidize the basics). The store relocated to another address also in Vancouver. New clientele heard about the store by word-of-mouth, and staff instructed customers to keep the operation on the down-low.

Every once in a while a journalist would get his or her hands on the story and cause a minor uproar. One of these journalists nicknamed the store “Pirate Joe’s”, and it stuck – “it ended up being convenient shorthand for our tagline: ‘unauthorized, unaffiliated, and unafraid.’” Hallatt hired shoppers across the border to help him with runs, (“I can’t hire Canadian because it requires a work Visa, turns out.”). Sometimes specific shoppers got banned from specific stores, which just meant they had to rotate to a new beat.

This went on for about a year and a half. Then, in May of 2013, Trader Joe’s sued Michael Hallatt.

The Grey Area of the Grey Market

Back when Hallatt was just forming the idea for Pirate Joe’s, there was one thing he heard a lot of: “You’re gonna get sued.” This came from everybody he talked to — from friends telling him, “this is absolutely insane” and hysterically trying to shout him down, to friends level-headedly and gently suggesting, “ah, dude, why don’t you just find something else to do?”

But Hallatt was determined, so he did a little research. One term that kept turning up was grey market.

Pirate Joe’s isn’t technically engaging in piracy. The stock isn’t stolen (Hallatt pays retail to Trader Joe’s for all his stock), counterfeit (Hallatt’s products are advertised as Trader Joe’s products, and are in fact Trader Joe’s products), nor technically smuggled (Hallatt declares his haul at customs, and he doesn’t stock alcohol — which is especially regulated). But Pirate Joe’s is dealing in a grey market, or the trade of a product outside of its official, authorized distribution channel. Authorized goods are white market, illegal goods are black market; grey market goods are somewhere in between.

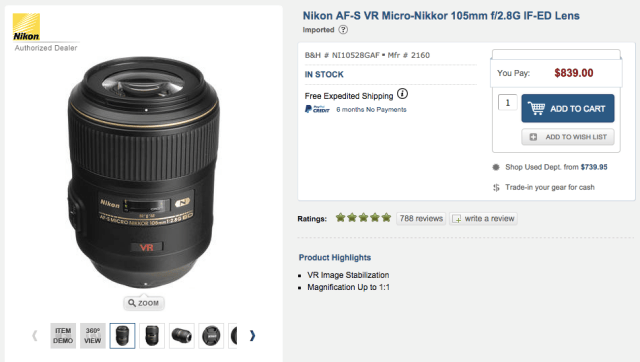

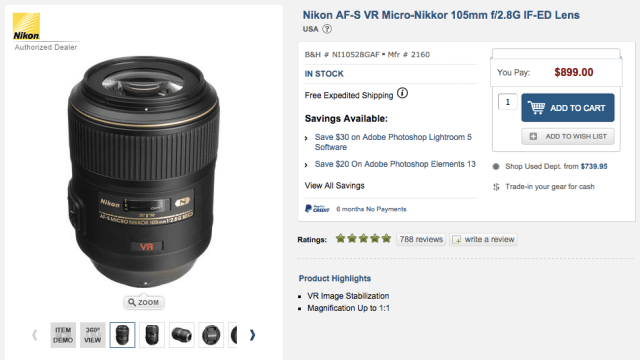

A classic example of a grey market is the online retail of electronics equipment. Suppliers will set different prices for the same product in different regions, but an online customer can opt to import a product from a cheaper region if he or she choses. For example, this Nikon lens costs $839 as a grey market import, and $899 from the official US distributor – from the same online retailer, which also provides free expedited shipping for both items.

A grey market import sells for cheaper than the one from the official US distributor

Selling products acquired through “unofficial” channels is something that many respectable retailers do in the open, without necessarily incurring the legal wrath of their suppliers. Hallatt even discovered that Joe Coulombe himself – the original owner and CEO of Trader Joe’s, which is now controlled by the German owners of a discount supermarket chain – defended his decision to sell grey market stock in the 1980’s. According to a 1988 article in the LA Times, in 1985 Trader Joe’s sold bottles of Dom Perignon for $33 a pop — about half its price at many other stores:

“’It was stupid to buy from official sources,’ said Joe Coulombe, chairman of Trader Joe’s, which used to buy all its French champagne from gray market sources. ‘We sold millions of dollars of stuff.’”

Hallatt says he still has a lot of respect for Trader Joe’s, and “what they’re trying to do with food.” He still says he’s running the store out of love for the label, and, he says, finding Coulombe’s quote is one of the things that made him persevere through the lawsuit.

Hallatt also learned that a lot of grey market entrepreneurs had battled regulation and won. One college student in particular had his friends in Asia send him many copies of textbooks, which he then resold to an American clientele on eBay, netting an estimated $100,000 in profit. The textbook publisher took him to court, and the student fought back, claiming he was protected by the first sale doctrine, which NPR summarized as, “once you buy a product, it is yours to do with as you please.”

The case made it to the Supreme Court, which ruled in the student’s favor. From Justice Breyer’s reading of the court opinion:

“We ask whether the ‘first sale’ doctrine applies to protect a buyer or other lawful owner of a copy […] lawfully manufactured abroad. Can that buyer bring that copy into the United States (and sell or give it away) without obtaining permission to do so from the copyright owner? Can […] someone who purchases […] a book printed abroad subsequently resell it without the copyright owner’s permission?

In our view, the answers to these questions are, yes.”

The decision came just months before Trader Joe’s sued Hallatt.

Pirate versus Goliath

Another sign at the Pirate Joe’s checkout

Once he knew where to look, Hallatt called some lawyers who specialized in grey market law for a free consult. One of the things the lawyers turned up was that Trader Joes had a history of suing people for infringing on their trademark.

But the thing is, even knowing of Trader Joe’s legal history, the lawyers didn’t all shut him down. “One guy said,”Hallatt reported, dropping his voice to a whisper to quote the attorney, “‘You can totally do this. I normally crush guys like you but you can totally do this.”

Another pair of lawyers argued about it until they came to an impasse. “There were a few beats of silence,” Hallatt said, “and then one of them said, ‘You should take fact that we can’t say ‘no’ as a really good sign.’”

“But then they wanted a retainer to stay on and keep me from getting sued, and I didn’t have the money for that!” Hallatt said, laughing.

When he did get slapped with a lawsuit, he “thanked God” he had valid business insurance – which is how he’s afforded his legal fees.

Last December, the case was dismissed with prejudice – Hallatt won. Trader Joe’s is appealing, of course.

The biggest issue with the lawsuit was that Pirate Joe’s is in Canada, and Trader Joe’s, and their lawsuit, were not. The exact language in the case:

“Plaintiff does not state a claim upon which relief can be granted because the [Washington laws] do not apply where no Party is a Washington resident, all allegedly wrongful conduct occurs out of state, and any harm to Washington residents is extremely tangiential if existent.”

This leaves Pirate Joe’s in a reverse catch-22 — the court says Trader Joe’s doesn’t have a claim if they don’t have a presence in Canada. If Trader Joe’s ever opens a Canadian store, they might have a claim. But Hallatt’s ultimate goal with Pirate Joe’s is to “bring” Trader Joe’s to Canada — before he had the store he would call them and just petition them, and he has always promised to close up shop if they ever expand north. In many ways, Hallatt would count this as the ultimate victory. “I’d take a little backhanded credit for it,” he jokes, “and then move onto the next thing.”

The case attracted a lot of media attention, and speculation by legal experts in a few popular outlets. Some of them, along with Hallatt’s lawyers, pointed out that the case would be shaky even if it weren’t straddling a national border. Law Professors Kal Raustiala and Chris Sprigman wrote about it in the Freakonomics blog:

“Trademark law doesn’t confer on trademark owners the right to control subsequent unauthorized resales of genuine products, at least if the reseller doesn’t alter the product in a way that confuses consumers. [Pirate Joe’s] doesn’t do anything to the [Trader Joe’s] products other than truck them across the border in a white panel van.

“If [Trader Joe’s] has the right to stop [Pirate Joe’s] from reselling their products, then any trademark owner might assert a similar right. Ford could sue Carmax for reselling Fords. […] And if this were true, a trademark law that is aimed at preventing consumer confusion will be preventing something else entirely – competition.”

Business as Usual

When Trader Joe’s sued, Hallatt took down the “P” in the window display’s “PIRATE”, so it would read “IRATE JOE’S” — Hallatt’s version of a flag at half-mast

If you call Pirate Joe’s during the off-hours, or while the staff are too busy to answer the phone, you’ll hear Hallatt’s scratchy voice on the recording:

“Hi you’ve reached Pirate Joe’s we’re located at 2348 West 4th Street […]

We do not sell Trader Joe’s products. You might have heard we do, we don’t. That would be unfair to Trader Joe’s, to go down there and buy groceries from them. Say you bought like maybe a million dollars worth of groceries from them over three years, that would be grossly unfair, paid cash. Terrible terrible. So, you know, we don’t. We didnt do that.”

“HA!”

“Come on down, check out what we got. Or call us back, bug us, we’ll pick up we’ll tell you what we’ve have. Mostly costumes [unintelligible].”

This is Hallatt kidding around. But he’s also courting his store’s naturally surreal aesthetic. Hallatt says he loves new customers who show up visibly uneasy.

“There’s a hesitation like, ‘Am I going to get arrested?’” Hallatt said. It helps if there are a lot of holes in the shelves at the time. “Maybe somebody came and took all the damn mangoes or something. And we say, ‘We’ve got someone shopping right now, it’ll be back in a few days.’”

Hallatt seems to relish how the sloppiness of his store disrupts the normally transactional culture of buying groceries. “You usually walk into a grocery store thinking ‘OK I gotta get my stuff and get going, I’ve got two quarters in the meter.’”

“But Pirate Joe’s is a dangerous place to come into.”

“We try to give them a basket and they know what that means. If they grab a basket, they’re in trouble. So then we offer them chocolate.” Hallatt laughs, “The chocolate is usually a pretty effective icebreaker.” Eating chocolate, they’re comfortable enough to ask questions, and he tells them his story.

Earlier this year, “docu-reality comedy” Nathan for You, made a splash by opening a “parody” Starbucks. They claimed they could use Starbucks’ trademarks partly because their store wasn’t really a store, it was a piece of ‘performance art’. If the appeal goes south for Hallatt, his lawyers might want to try this tactic. He’s in it for the adventure, the romance, the ideals, and the drama – which isn’t something every small business owner can say.

Even a pirate’s life has it’s lulls. “It’s so boring right now. I’m craving something,” Hallatt told us, when we asked how business is going. He’s eyeing a second location, farther from the border. The shipments come in steadily enough. He’s got 8 or so shoppers working right now, spending a couple thousand a week. He still does the border crossings himself, sits in line for hours in an unmarked white van. The workload is still enormous. Hallatt jokes that whenever a cab goes by, he envies the driver’s salary.

But he’s still at it. A few years back, his old software friends invited him to work with them as a developer for Wells Fargo. He probably could still get back into development if he wanted to, but his heart belongs to the store.

Part of his fidelity to the place is political – he says that even with the “pirate” mark-up, his products are often a better deal than those found at the Safeway across the street, and for that to be the case there must be something wrong with Canada.

Another part of it is that the store has become a minor tourist site. The whole lawsuit was a bath in the limelight for Hallatt. He was interviewed for newspapers, radio, and he made a few television appearances, (“I made Fox News send a limo because I hate Murdoch.”). Kids from the Sauder School of Business come by every once in a while to check the place out and do a case study, (“I tell them it isn’t a business model it’s a stunt!”). People come from all over just to see his store. One guy, from the “outer reaches”, came to shake his hand and tell him he was proud.

“How do you quit when you have that kind of encouragement?” Hallatt pleads. “I end up having to suspend my own rational thinking. I’ve never worked harder for less money in my life.”

If you enjoyed this post, you’ll like our book → Everything Is Bullshit.

This post was written by Rosie Cima; you can follow her on Twitter here. To get occasional notifications when we write blog posts, please sign up for our email list