“Along with the heroin, cash, weapons and other stuff you would expect, we kept finding these tiny McDonald’s spoons they give out for stirring tea and coffee.”

~ A Scotland narcotics detective, 1998

![]()

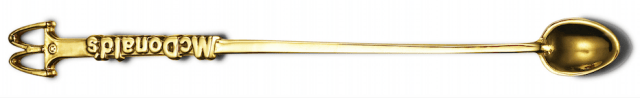

In the 1970s, every McDonald’s coffee came with a special stirring spoon. It was a glorious, elegant utensil — long, thin handle, tiny scooper on the end, each pridefully topped with the golden arches. It was a spoon specially designed to stir steaming brews, a spoon with no bad intentions.

It was also a spoon that lived in a dangerous era for spoons. Cocaine use was rampant and crafty dealers were constantly on the prowl for inconspicuous tools with which to measure and ingest the white powder. In the thralls of an anti-drug initiative, the innocent spoon soon found itself at the center of controversy, prompting McDonald’s to redesign it. In the years since, the irreproachable contraption has tirelessly haunted the fast food chain.

This is the story of how the “Mcspoon” became the unlikely scapegoat of the War on Drugs.

The War on Drug Paraphernalia

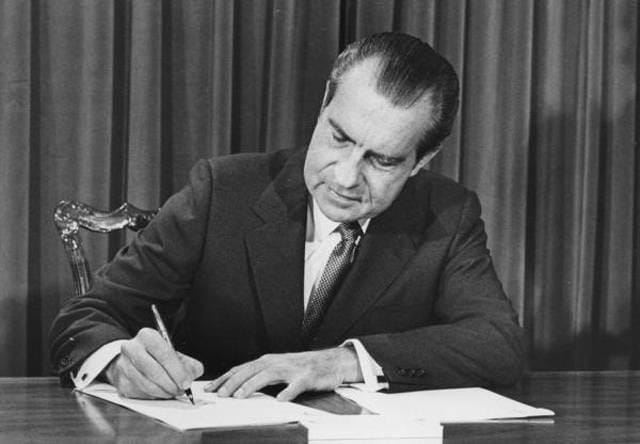

On June 17, 1971, President Richard Nixon stood before his peers in the White House’s briefing room and officially initiated the War on Drugs. “America’s public enemy number one in the United States is drug abuse,” he told a panel of reporters, “and in order to fight and defeat this enemy, it is necessary to wage a new, all-out offensive.”

In the ensuing eight years, the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) was born, plans were put in place to dismantle the Colombian cocaine trade, and thousands of questionable arrests were made. Nixon’s initiative conversely increased drug use. Throughout the 70s, cocaine experienced its golden age: By 1979, the drug — touted as the “champagne of drugs” by The New York Times — was being ingested by 11% of adult Americans.

At the same time, a rhetoric emerged among anti-drug campaigners that these problems stemmed from the use and sale of paraphernalia (coke spoons, pipes, rolling papers, etc). National Families in Action, formed in 1977, successfully lobbied to pass several laws prohibiting the sale of drug paraphernalia. By 1979, just as cocaine use peaked, the DEA proposed the Model Drug Paraphernalia Act, which set in place an incredibly vague definition of what constituted “paraphernalia:”

“The term ‘drug paraphernalia’ means any equipment, product, or material of any kind which is primarily intended or designed for use in manufacturing, compounding, converting, concealing, producing, processing, preparing, injecting, ingesting, inhaling, or otherwise introducing into the human body a controlled substance…”

Due to its ambiguous language, the law wasn’t adopted on a federal level — but it was enacted by almost every state government (in some cases, verbatim), and it placed unlikely household items under the umbrella of drug paraphernalia. A sandwich bag in proximity to a few nuggets of weed or a silly straw near a line of coke were now “items of suspicion.”

In the midst of this political rubble, McDonald’s innocent little coffee spoon found itself at the center of the discussion.

A Spoon’s Loss is a Lobbyist’s Victory

Just prior to the creation of the Model Drug Paraphernalia Act, then-Senators Joe Biden and Charles Mathias held a hearing in Baltimore, where the Paraphernalia Trade Association (who represents headshop vendors) could voice their concerns. The PTA swiftly went about arguing that, under such a broad definition, anything could be deemed “paraphernalia.”

According to minutes from the hearing, one PTA representative attempted to make a mockery of the proposed law. “Look at this,” he facetiously told the panel, thrusting a McDonald’s coffee stirring spoon above his head. “This is the best cocaine spoon in town and it’s free with every cup of coffee at McDonalds.”

With its long, thin handle and tiny stirring head, the McDonald’s spoon had, indeed, amassed a cult following among drug dealers and aficionados. Light, cheap, and inconspicuous, it could be concealed easily — and best of all, as its scoop held exactly 100 milligrams of product, it doubled as a measuring device.

While the representative’s intention was to deride the anti-drug crusaders’ attack, his stunt fell on the wrong ears — those belonging to former President of the National Federation of Parents for Drug-Free Youth, Joyce Nalepka. Though Nalepka left the hearing without a chance to testify, she spent her whole drive home “searching for some way to counteract [the PTA’s] McDonald’s spoon statement.”

Then it hit her: she’d contact McDonald’s, inform the company of its utensil’s bad rap on the street, and demand they discontinue it.

Nalepka phoned the chain’s corporate office and, through some sweet talking, got through to its president, Ed Schmidt. “What do you want from me?” he asked her, as she began to explain the problem.

“The drug paraphernalia industry says your tiny spoon-shaped coffee stirrer is being used as a cocaine spoon,” answered Nalepka. “I’m testifying before the U.S. Senate tomorrow, and I want you to say you’ll redesign the spoon and allow me to go back to the Senate hearing and announce that you don’t want to have your company associated with drug paraphernalia.”

“We have 4,500 stores,” retorted an unfazed Schmidt. “It’s not going to happen.”

Nalepka persisted, this time employing an emotional siege. “Well, would you consider doing this for your children, and for my kids and America’s kids? Go the extra mile.”

Schmidt asked the persistent lobbyist to call him back in twenty minutes; when she did, his answer was curt: “We’ll do it.”

***

The following day, Nalepka attended a senate hearing on drug paraphernalia and youth, where she proudly announced her victory:

“The paraphernalia industry has told us several times that the McDonalds restaurant coffee stirrer makes an adequate cocaine spoon; this disturbs me — to kids, McDonald’s is All-American. Last evening, Mr. Edward Schmidt, president of McDonald’s restaurants, gave me permission to announce to you that the company will either redesign or discontinue the item altogether. This is an important statement from the business community.”

Joyce Nalepka at a conference in 2008

Following the hearing, Nalepka sent out a press release and received a tremendous response, much to the chagrin of the Paraphernalia Trade Association and other anti-drug war folks. While Nalepka later reflected that her successful ban of the McSpoon “didn’t stop the drug epidemic,” she claims it “left a large imprint that responsible businesses were ready to help [ban paraphernalia]:”

“After that, [opposers] would sit behind us when we testified in state legislatures or the U.S. Congress and call us names while we spoke. They’d ask us questions like, ‘What’s next? Are you going to ban swizzle sticks and shot glasses?’ The chiding came from print as well as electronic media.”

Among these dissenters was Kenneth Bombard, a child psychologist at Duke University who argued that the vagueness of what defined paraphernalia was a slippery slope. “Many common articles are used every day as paraphernalia,” he told a panel. “The loss of the McDonald’s coffee spoon is a tragedy, and only the beginning of what’s to come under this law.”

Still, McDonald’s ceded to anti-drug pressure. “It has been brought to our attention,” the family-oriented company stated in a press release, “that people are using [our spoons] illegally and illicitly for purposes for which they are not intended.” With that, in December 1979, the ‘McSpoon’ bid adieu.

The Inglorious Return of the McSpoon

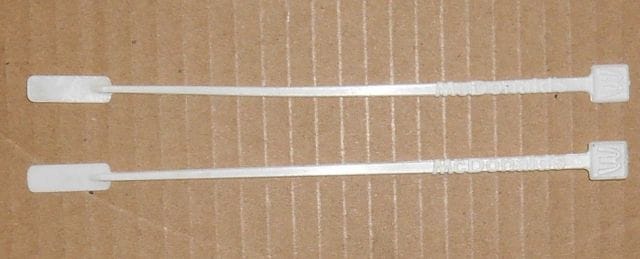

In early 1980, McDonald’s redesigned and released its new coffee stirring spoon — a much flatter one with a paddle instead of a small scooper. While the move sated anti-drug lobbyists, it did little to curb cocaine use.

During its life at McDonald’s, the utensil had become so unanimously popular with drug dealers, that ‘McSpoon’ became a common slang term on the streets, referring to the specific amount of cocaine the spoon held (exactly 100 milligrams). In 1992, more than a decade after the spoon had been discontinued, a DEA agent told the Columbus Dispatch that dealers were still using the “measurement” to dole out the drug. “A bundle of cocaine,” he clarified, “includes ten McSpoons.”

This wasn’t the only trouble brewing for the spoons. After terminating and redesigned the spoons in 1979, McDonald’s was left with millions of the old ones in storage. To rid its supply, the company continued disseminating them to its franchises abroad. Soon enough, the spoons began to cause a ruckus elsewhere.

In December 1998, during a 250-home narcotics sweep, detectives in Edinburgh, Scotland came across an unlikely item. “Along with the heroin, cash, weapons and other stuff you would expect,” said one police insider, “we kept finding these tiny McDonald’s spoons they give out for stirring tea and coffee.” It was later determined that drug dealers had been using the spoons for years to measure heroin (and the glucose used to dilute the drug). Unlike scales, which were often used as evidence of drug dealing in court, the spoons posed a minimal risk under Scottish paraphernalia laws.

When McDonald’s was informed of the situation, the company quickly replaced the spoons with the flat-edged US version. “”We have regular consultation with the police and it was something they asked us to take a look at,” a company spokesman told the Scottish Daily Record. “As a responsible company, we try to work closely with the police.”

A Never-ending Plight

“Cokespoon No.2”

While the cursed spoons were completely eradicated by McDonald’s, they have continued to haunt the company. Long-replaced by tiny plastic straws (which, according to one customer, totally suck), the original spoon still seems to have a cult following and can be copiously found on auction sites for $4-5 each.

In 2005, San Francisco-based artists Ken Courtney and Tobias Wong purchased one on eBay and proceeded to cast a gold-plated “exact replica” of the old McDonald’s spoon. The spoon, aptly christened “Cokespoon No.2,” was subsequently featured in high-end art galleries, reproduced, and sold as a $295 novelty item.

McDonald’s didn’t appreciate the joke.

In 2007, citing the “association of [its trade]marks with illicit drug activity,” the fast food chain sent the artists a cease and desist. Like the real spoon, the golden replica was discontinued.

“Designers and manufacturers have a very specific and clear idea of the function of the objects that they make,” Wood later told a reporter. “And yet, when it arrives into society and culture, you really have very little idea control over what it’s then used for or even how it’s valued as well.”

![]()

If you enjoyed this post, you’ll be mildly amused by our book → Everything Is Bullshit.

This post was written by Zachary Crockett. Follow him on Twitter here, or Google Plus here.