This article was written by Zachary Crockett

![]()

On a winter morning in 1994, Massachusetts resident Fred Boyce turned on his car radio, and was shocked by what he heard. A federal committee had just revealed that 50 years earlier, a group of children at Fernald State School—an institution for the developmentally disabled—had been unwittingly fed radioactive cereal by MIT researchers.

“That can’t be right!” he yelled. “That’s me!”

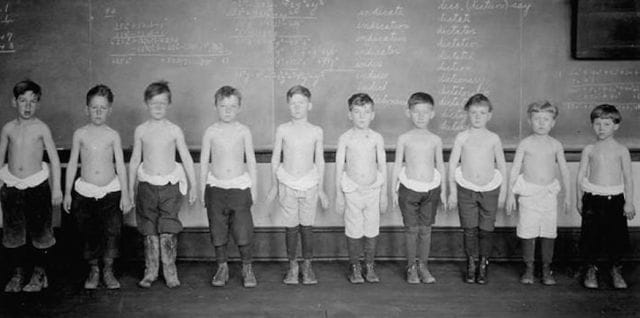

In the late 1940s, Boyce was one of some 90 children, most of whom were classified as “feeble-minded,” selected by MIT to be used as test subjects. With offers of free meals and Boston Red Sox tickets, they’d been coaxed to join a “Science Club” without knowing that their inclusion would make them guinea pigs for various radiation-laden nutrition studies funded by Quaker Oats.

It wasn’t until decades later, on that winter morning in 1994, that Boyce became aware of what he’d been secretly put through. It incited one of history’s most searing debates about the ethics of academic research and the necessity of informed consent.

The “Science Club”

In the late 1940s, two major brands, Quaker Oats and Cream of Wheat, were competing for cereal market share. At the same time, cereals in general were under a bit of nutritional scrutiny: a series of experiments had revealed that plant-based grains contained naturally high levels of phytate, an acid that inhibited the absorption of iron and calcium.

When MIT decided to look into how the human body absorbs essential minerals and vitamins, Quaker jumped at the opportunity to fund the study, largely out of a desire to “give them an advantage over Cream of Wheat.”

After securing additional grants from the National Institutes of Health and the Atomic Energy Commission, MIT formulated a plan: they’d “recruit” 40 children from the Fernald State School, an institution for the developmentally disabled, and feed them cereal with radioactive tracers (which, even today, are used to trace processes in the human body).

***

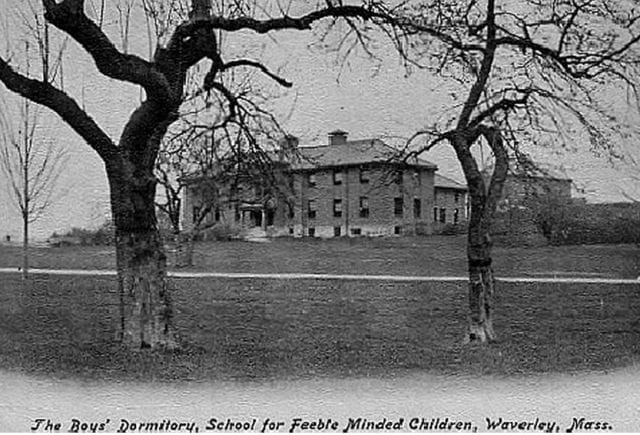

Originally dubbed ‘The Massachusetts School for the Feeble-Minded,” Fernald State School was the first institution in the United States designed for developmentally disabled children. But it was founded on morally dubious principles.

At the turn of the 20th century, Walter E. Fernald became the school’s superintendent. Fernald, who trumpeted the school as a “model in the field of mental retardation,” was a leading proponent of the growing eugenics movement in the United States. The 2,500 children at Fernald were not all developmentally challenged. Some were transferred from shelters, or abandoned their by their parents. But they all were ingrained with the same mentality: that they were not “part of the [human] species.”

For MIT—one of the country’s premier universities—the Fernald Center was the perfect place to conduct research. Subjects were easy to coax into participating, were an ideal control group, and, most importantly, were oblivious to whatever they were being subjected to. When researchers began their Quaker Oats-funded study in 1949, they knew just where to go.

Fernald Center, then named a “School for the Feeble Minded ”(c.1900)

The plan was simple: to feed children copious amounts of Quaker Oats cereal, and track the natural absorption of iron and calcium using radioactive tracers. To recruit test subjects, MIT created a vaguely-titled “Science Club” at Fernald, promising that any child who joined would get “special privileges.”

In a Senate hearing 40 years later, Charles Dyer, who was seven at the time, recalled being coaxed to join the Science Club by MIT researchers. “They gave me a Mickey Mouse watch,” he said, “and they made me feel special.”

Another Science Club member, Austin LaRoque, thirteen at the time, would later describe MIT’s tactics as “misleading:”

“They said [the Club] would benefit us by taking vitamins and stuff. They took us places here and there. [MIT] said they were going to have a Christmas Party for us. And we were young kids. They took advantage of us. We were youngsters. We figured well, we got a chance to get off the grounds for a while, get and and see something—we’ll do it.”

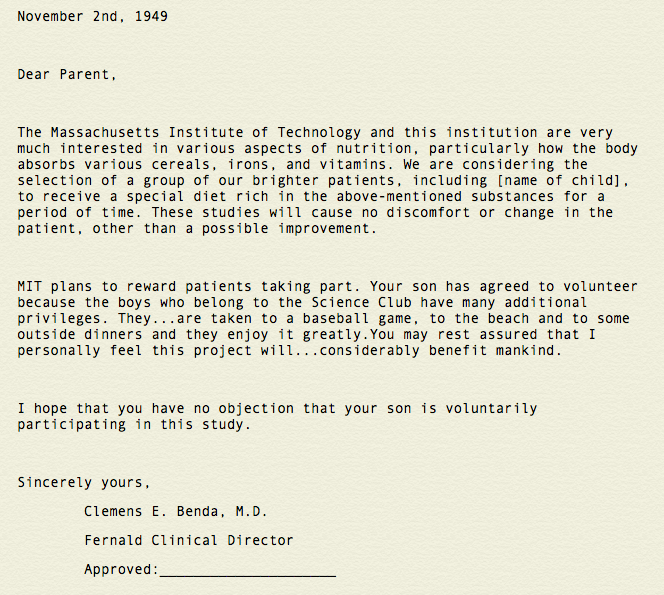

After convincing some 40 youngsters to join the Science Club, MIT then sent out a letter to the children’s parents—many of whom had abandoned them and hadn’t been in touch for years. Rather than mention radioactive exposure or the potential dangers faced by participants, the letter (reproduced below) harped on the benefits Science Club members would receive:

“Some of us had to sign our own forms, but at that particular time I could not read or write,” recalled Austin LaRoque, years later. “I had no knowledge of anything other than the fact that I do what I’m told when I’m told.”

Over the next several weeks, Dyer, along with a few dozen kids between the ages of 7 and 17, were fed “rather large” amounts of Quaker Oats cereal coated with radioactive chemicals, which allowed the researchers to trace the digestion process. The results, which proved that the iron absorption rate of rolled oats was no less than that of farina (Cream of Wheat), “greatly pleased” the Quaker Oats Company.

Some months after the iron experiments, Fernald Science Club members were subjected to a series of tests related to calcium intake. This time, 36 youth each received two breakfasts containing milk (with a radioactive tracer in calcium). The goals was to understand whether or not the phytate chemicals inherent in plant-based cereals “interfered with the dietary uptake of calcium.” Once again, the results were favorable for Quaker: the study found that oatmeal, when combined with milk, provided a sufficient level of calcium.

In a third set of experiments, which sought to understand what happens to calcium in the bloodstream, nine Fernald Science Club youth were injected with syringes full of radioactive calcium. Though obtained immorally, the knowledge acquired from this test eventually laid the foundation for much subsequent research in osteoporosis.

Upon concluding their tests, MIT ended its association with Fernald. Though researchers never followed up with any of the test subjects, they had plenty of time to share their new knowledge with Quaker Oats, whose “high in iron” claims became a vital component of their advertising campaigns.

It would take more than 40 years for the details of the study to be excavated. When that happened, it came with considerable consequences for MIT, Quaker Oats, and everyone else involved.

The Past, Revisited

In December of 1993, Scott Allen, a journalist at the Boston Globe, unearthed a trove of papers that documented years of ethically dubious studies conducted on Fernald Center youth. The day after Christmas, he published an article, “Radiation Used on Retarded”, that not only ignited a national debate on the ethics of medical research, but inspired the federal government to launch an investigation into the matter.

What followed was a series of Senate committee hearings on human subjects radiation research. MIT’s Fernald Science Club experiments were right at the center of the scrutiny. The investigators’ immediate concern was identifying just how much radiation the Fernald children had been exposed to.

David Litster, then-Vice President of Research at MIT, faced the daunting task of defending his institution’s shady ethical past. The amount of radioactive exposure, he said, was “minute” and varied based on the subjects’ body weight.

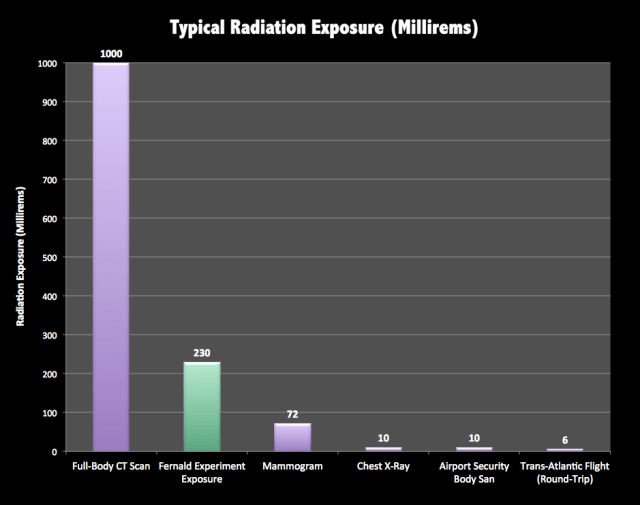

“[For the iron experiment], exposures ranged from 170 millirems to 330 millirems, with an average of 230,” he told the committee. “For the calcium experiments, it was much less, like 12 millirems or less.”

To put these numbers into perspective, 300 millirems is roughly equivalent to receiving 30 consecutive chest x-rays, or one year’s worth of background radiation exposure in a city like Boston—an amount, added Litster, that carried an extra risk of contracting cancer in one of 2,000 cases.

Priceonomics; Data via U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission

IIn experiments of this nature, radioactive tracers were, and still are, commonly used to track chemical reactions within the human body. By itself, the use of them at Fernald was not incredibly controversial.

The more pressing concern was how the experiments were conducted: without informed consent. The letter MIT sent to parents, Representative Joseph P. Kennedy II told the committee, was “deceptive, at best.” Again, MIT defended its actions—this time with some historical background.

At the time of MIT’s study (1949-50), the concept of “informed consent” (or that a human test subject had the right to know exactly what he or she was being subjected to) did not exist. It wasn’t until 1953 that the National Institutes of Health created the first federal policy protecting human subjects; by 1966, the Public Health Service had followed suit, pronouncing that freely given consent was the “cornerstone of ethical experimentation.” The National Research Act of 1974 delineated, for the first time, an across-the-board procedure for conducting ethical research, and it designated that an institution review board (IRB) had to approve research based on informed consent (and a clear description of the risks involved).

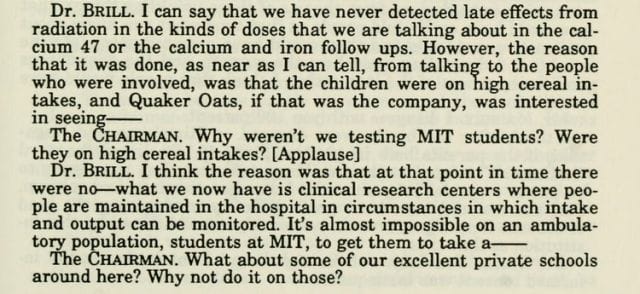

But any work conducted prior to the early 1950s, like MIT’s Fernald Science Club experiments, could be “justified” by the lack of any ethical guidelines. When MIT’s research director, Dr. Bertran Brill, stepped to the podium, he attempted to defend his institution’s choice of using developmentally-challenged children for the study by claiming that they ate more cereal than most people:

Excerpt taken from the Senate Committee hearing Human Subject Research (Radiation Experimentation); January 13, 1994

“I admit they shouldn’t have focused on a population that was so captive and had no alternative,” later ceded Dr. Brill. “That was wrong.”

The Cost of Unethical Research

Shortly after the Senate hearings, legal advertisements were placed in newspapers across the state, imploring previously affected members of the Fernald Science Club, who were by then 60- to 70-years-old, to come forward. In 1997, a group of roughly 30 men, many of whom had mental and physical disabilities, filed a class action lawsuit for $60 million on the grounds that their civil rights had been violated.

The Massachusetts Task Force, which investigated the case, eventually determined that “The letter in which consent from family members was requested…failed to provide information that was reasonably necessary for an informed decision to be made.”

Though MIT maintained that “its researchers acted properly under existing standards of conduct,” they, along with Quaker Oats, agreed to pay out a settlement of $1.85 million to those they’d experimented on decades earlier. According to the original press release, this was merely to “avoid the expense and diversion of a lengthy legal battle.”

“I look on it as the tuition of 20 students,” Vice President of Research, David Litster, told the press. “I got quite a dose of x-rays every time my parents took me to the shoe store—far more than the people got who participated in some of these studies 40 years ago. Does someone owe me an apology, and perhaps a monetary settlement?”

Questions like these sparked a long-standing debate about ethics in research—a debate which saw defensive academics contending against citizens who felt that past research had violated people’s rights. In a 1994 letter to the New York Times, one reader passionately opined the latter stance:

“While this situation may not have been thought to be fraught with medical difficulties, it was contaminated by ethical doubts. Informed consent was cast aside, a slippery slope was put into place, and we all know that leading down that slope was a barbaric chasm.”

“This was about secrecy, an utter disregard for human safety,” agreed a Harvard School of Medicine professor. “All I can say is we can do good research by being honest and fair with people. That’s the only way to do it. If you don’t do it that way, it will backfire.”

Our next post looks at the organization raffling off a swank house amongst the housing scarcity of San Francisco. To get notified when we post it → join our email list.

An earlier version of this story was published on February 26, 2015.

***

Note: If you’re a company that wants to work with Priceonomics to turn your data into great stories, learn more about the Priceonomics Data Studio.