The thesis that the Internet is making us stupid – or that the constant distractions of the toys and tools of the digital age keep us from concentrating or thinking deeply – is not a new one. And given how increasingly common it is to work with music playing, a text messenger open, and email notifications popping up, we at Priceonomics find that the person expressing it can sound like a nagging grandparent who thinks the world was perfect in the 1950s and everything since has been a disappointment.

The recently published work of three researchers at Stanford University, however, supports the idea. It suggests that multitasking may not only hurt your ability to focus on a single task, but you may actually get worse at multitasking the more you do it.

The stakes in the debate are high because we constantly perform the processes involved in multitasking. The classic example in psychology and neuroscience is the cocktail party effect, which describes how partygoers seem to “tune into” their conversation while tuning out the multitude of other voices in the room. Yet people suddenly tune into a conversation across the room when they hear their own name mentioned – even though they seemed oblivious to the conversation before.

Although people frequently discuss sensory overload as a new phenomenon, every environment has too much information to process. So, we selectively apply our attention to what is important. We ignore nearby street signs while driving to focus on traffic lights and ignore sounds in the street while reading a book – but we will take note if a child runs out into the street or if the sounds from the street include a voice shouting “Fire!” A multitasker faces an overwhelming amount of information and decides how to divide his or her attention among it, but the same is true of every situation. The difference is whether we actively try to tune out all but one activity or whether we try to attune ourselves to multiple sources of information.

People generally recognize that multitasking involves a trade-off – we attend to more things but our performance at each suffers. But in their study “Cognitive Control in Media Multitaskers,” Professors Ophira, Nass, and Wagner of Stanford ask whether chronic multitasking affects your concentration when not explicitly multitasking. In effect, they ask whether multitasking is a trait and not just a state.

To do so, they recruited Stanford students who they identified as either heavy or light “media multitaskers” based on a survey that asked how often they used multiple streams of information (such as texting, YouTube, music, instant messaging, and email) at the same time. They then put them through a series of tests that looked at how they process information.

A first experiment judged the students’ ability to filter out environmental distractions when focusing on a task. The equivalent of judging someone’s ability to tune out other conversations at a cocktail party, it instructed participants to note whether a rectangle changed orientation or identify a particular series of letters. Students were simultaneously distracted by rectangles or letter pairs of a different color that they were instructed to ignore.

As we see below, those who did not regularly multitask had higher accuracy and a faster response time, which suggested they could better filter out the extraneous information.

Results from the shape task (left) and letters taks (right). LMM = light media multitaskers. HMM = heavy media multitaskers. Source: Cognitive Control in Media Multitaskers.

A second test tackled the question of how multitasking affects working memory. The students saw a series of letters flash on a computer screen. After two or three series, they were shown a single letter and asked whether the single letter had been present on a specified previous screen.

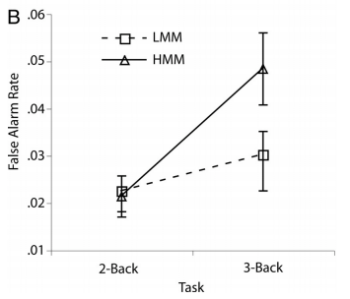

Although light multitaskers slightly outperformed heavy multitaskers, the most striking result was the increase in the number of false alarms (wrongly indicating that the letter had been present in the previous screen) by heavy multitaskers as the task got more complicated. As the false alarm letters had previously appeared (just not on the correct screen), the researchers interpreted this as a sign that multitaskers “were more susceptible to interference from items that seemed familiar, and that this problem increased as working memory load increased.”

Hit rate in A corresponds to correct identifications. The 3-Back test is more difficult than the 2-Back test (i.e. remembering letters from 3 screens prior instead of 2). LMM = light media multitaskers. HMM = heavy media multitaskers. Source: Cognitive Control in Media Multitaskers.

A final experiment had the students perform two short tasks similar to the ones above. To test the participants’ ability to switch between different tasks, they alternated irregularly between performing the same task multiple times in a row or switching back and forth between the two tasks. The researchers then measured the delta between the amount of time participants took to complete a task when it was either the same or different one than the previous task.

People generally get better at activities they do often. But that may not be true of multitasking. Since heavy multitaskers often switch between research and emails or Facebook chats and work, we’d expect them to outperform the light multitaskers at switching back and forth between the two tasks. But they actually performed worse as their delta was higher than that of the light multitaskers.

The professors conclude that frequent multitaskers seem to “have greater difficulty filtering out irrelevant stimuli from their environment, [be] less likely to ignore irrelevant representations in memory, and are less effective in suppressing the activation of irrelevant task sets (task-switching).” More colloquially, the multitaskers were more easily distracted from a single task and worse at switching between tasks.

The authors remain agnostic on the question of causality. Multitasking could change how people process information, they write, or people with a weaker ability for centralized focus could tend to multitask more than the average individual. The professors note that while their study only showed the shortcomings of multitaskers, multitasking may represent a different orientation rather than a deficit: Multitaskers may sacrifice performance at single tasks for a greater ability to respond to peripheral information, or think more exploratorily at the cost of focus.

But if the common hunch is correct and multitasking is causing these changes, it is troubling. It would support those who say that multitasking does not merely represent an in the moment tradeoff, but instead rewires our brains and changes how we think. It would suggest that multitasking follows us home from work to the cocktail party, where we find it harder to focus on our own conversation as we are distracted by peripheral details around the room and forget key details of our own exchange. And it would counterintuitively suggest that we get worse and worse at multitasking the more we do it.

This post was written by Alex Mayyasi. Follow him on Twitter here or Google Plus. To get occasional notifications when we write blog posts, sign up for our email list.