In the middle of a 1969 interview, writer E.B. White paused, smiled, and declared what he loved most about the publication he wrote for: “Commas in The New Yorker fall with the precision of knives in a circus act, outlining the victim.” An avid grammarian, the Charlotte’s Web author thoroughly enjoyed this routine.

Unfortunately, the United States government doesn’t share the magazine’s zeal for punctuation — and sometimes, it costs taxpayers money. Curious about the most expensive legislative typo in American history, we dug into the matter. If you’re anything like E.B. White, what we found will rile you up:

In 1872, one misplaced comma in a tariff law cost American taxpayers more than $2 million, or $38,350,000 in today’s dollars.

***

First, we should clarify that back in the old days, our government raised revenue a bit differently. After the United States gained independence from the British in 1776, it sought to economically reorganize itself through the establishment of a national budget. Thirteen years later, on July 4, George Washington signed the Tariff Act of 1789 into effect, stipulating that “duties be laid on goods, wares and merchandise” in order to “support the government.”

For over a century, these foreign import tariffs served as the primary source of the US government’s revenue — sometimes providing for as much as 95% of the federal budget overall:

Though income tax wasn’t permanently instituted until 1913-14, the first tax paid on individual incomes was actually levied in 1862, as part of a “patriotic war effort” to fund the Union cause during the Civil War. It was a “progressive” tax: Those who earned between $600-$10,000 per year paid 3% of their income, and those who made over $10,000 paid 5%; eventually, these rates increased to 5% and 10% (still as far cry from what most of us pay today). Over the ensuing eight years, the US government collected just shy of $100 million via this income tax.

Shortly thereafter, income taxes were abandoned, and tariffs once again accounted for the majority of federal revenue. On June 6, 1872, the United States government, under the administration of Ulysses S. Grant, issued its thirteenth tariff act — the first to come post-Civil War — which sought to reduce rates on many manufactured goods in order to get the economy back.

Instead, one miniscule typo ended up costing the government — and Civil War taxpayers — nearly $2 million.

This tariff act, like all previous acts, included a “free” list — items that were exempt from being taxed upon entry to the United States. All other foreign imports generally averaged a tax of around 20% of the good’s purchase price. Importers, always looking for ways to weasle lower fees on their goods, would voraciously scan new tariff acts when they were released in hope of discovering loopholes.

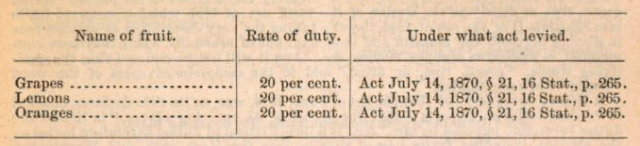

Duty rates on fruit from the Tariff Act of 1870

Subsequent tariff acts had specified that “Fruit plants, tropical and semi-tropical for the purpose of propagation or cultivation” were exempt from paying the import tariff. While plants and seeds used to “cultivate” fruit were exempt, fruit itself was not: Two years prior, the Tariff Act of 1870 had established a duty of 20% on oranges, lemons, pineapples, and grapes, and a duty of 10% on limes, bananas, mangoes, coconuts, and essentially every other fruit that was being imported to the US at the time. Fruit was a major import item, and as such, its tariffs constituted a considerable portion of the federal budget.

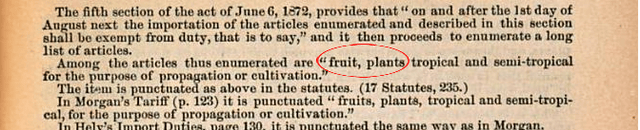

In the 1872 revision, a comma was, for some inexplicable reason, inserted between the words “fruit” and “plants,” giving fruit importers the means of evasion they’d been looking for:

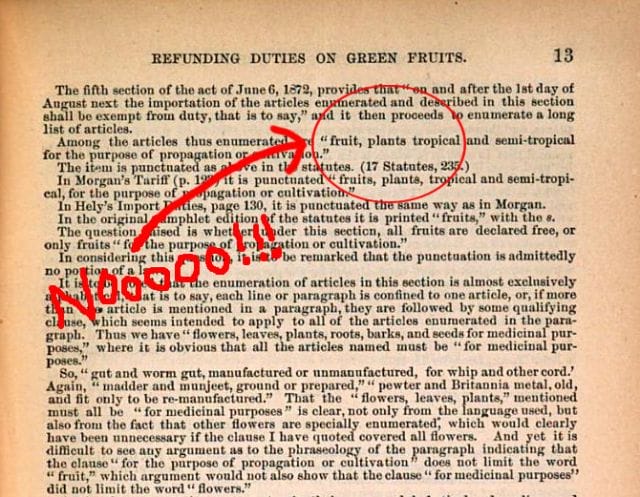

The comma, intended to read “fruit-plants” (with a hyphen, not a comma), had devastating consequences, recounts an article from the 1930s:

“The preamble of the ‘free’ list provided that all articles therein enumerated should be exempt from duty on and after Aug. 1, 1872. Certain importers asserted that the word ‘fruit’ in the free list of the Act of 1872 permitted the free entry of all tropical or semi-tropical fruits, and the claims [refunds on duties paid abroad] were filed on the shipments as they came in.”

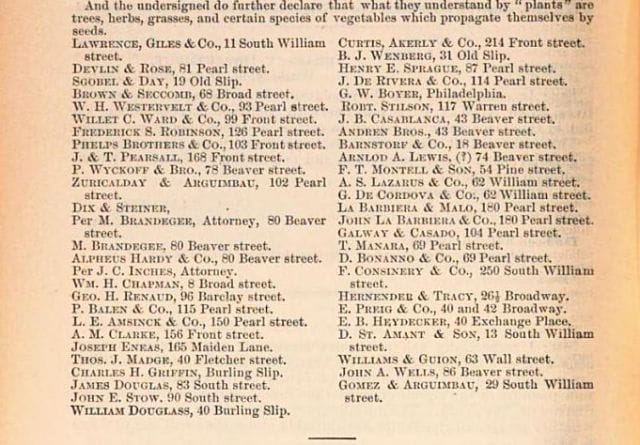

Initially, the Secretary of the Treasury rejected these claims on the grounds that the grammatical error was “clearly intended to read otherwise.” Importers, unwilling to accept this, ignited a series of trials on the matter (original documents here), and it soon became clear that the Secretary’s excuse wouldn’t hold up in the courtroom. In December 1874, two years after the typo, the US government declared that, under the phrasing of the act, fruits were free. Duties were subsequently refunded — to the tune of $2 million.

At the time, this was no small sum; a loss of $2 million was nearly 1.3% of the government’s total tariff income in 1875 ($157.2 million) — and 0.65% of that year’s entire federal budget ($308 million)!

A small sampling of fruit importers who filed for reimbursement

Under the headline “An Expensive Comma,” notes from the Forty-Third Congress were published in an 1874 New York Times article. During the hearing, legislators fiercely bickered over proper grammar usage — “The word fruit was used as a limitation, and not as a noun substantive!” declared one Congressman. One Senator, John Sherman, a republican from Ohio, was especially “anxious” to uncover the root cause of the improper comma, and had “hunted up all the papers relating to the subject.”

“The error occured by somebody adding ‘s’ to the word ‘fruit,’ and then a comma,” he stated. “We do not know who did it, but the subject should be inquired into.” Sherman, among other things, recalled a story in which “a learned judge of the United States Supreme Court” admitted to “never regarding” punctuation.

Eventually, after much debate, Congress concluded that there was “no doubt [the comma] was placed there honestly,” and the matter was dropped. In subsequent revisions of the act, duties of 20% were restored on all fruit, and life went on.

***

Years later, in 2006, a Canadian cable television provider faced an identical dilemma, when a lone comma error in a 14-page contract cost the company big bucks. The misplaced punctuation, prominently featured in the company’s legal terms, allowed for one of its major clients to prematurely escape a large contract. Despite a desperate attempt to draft a 69-page affidavit “mostly about commas,” the cable company eventually lost out on nearly $1 million.

“Why they feel that a comma should somehow overrule the plain meaning of the words is beyond me,” the company’s vice president later stated in a filing with the Telecommunications Commission. “[It’s just] a classic case of where the placement of a comma has great importance.”

Like hunting for typos? You’ll love our book → Everything Is Bullshit.

This post was written by Zachary Crockett; you can follow him on Twitter here. To get occasional notifications when we write blog posts, please sign up for our email list.