“I only go to a movie if it satisfies three basic requirements. One, it has to have at least two women in it, who, two, talk to each other about, three, something besides a man.”

So spoke an unnamed woman in a newspaper comic strip in 1985. Alison Bechdel, a 25-year-old comic artist, was hard-up for ideas that week, so she wrote her friend Liz Wallace into the strip. Wallace’s rule for avoiding cinema with an extreme male bias was ascribed to a character in the strip. The character claims she hasn’t been able to watch a movie since the 1979 space horror film Alien.

The Rule, by Alison Bechdel (via NPR)

30 years later, “The Rule” has become known as the Bechdel-Wallace Test, and it is everywhere. It is the subject of national newspaper editorials, and viral vlogs. It’s also penetrated the world of social science, where researchers have used the test to analyze historical trends in film and other art, and to amass large data sets on whether films pass or fail. They have even found ways of automatizing or extending the analysis.

If the test sounds too easy to pass to warrant all this attention, tell that to Hollywood. It turns out that from 1985 to 1989, 42% of blockbuster films failed the test. And 37% of films released from 2010 to 2014 failed.

Rosie Cima, Priceonomics; Data via BechdelTest.com

Out of 2015’s best picture nominees, only three — Boyhood, Selma and Birdman — featured two female characters who discussed anything other than a man. And, as Rachel Simon pointed out in Bustle, Birdman’s pass hinges on a “30-second scene consisting of two women talking about Broadway, before immediately changing the topic to men and kissing for no reason at all.” American Sniper, The Theory of Everything, The Grand Budapest Hotel, Whiplash, and The Imitation Game all unequivocally failed.

Who’s Afraid of Alison Bechdel?

Alison Bechdel in her studio. (Ricardo De Luca)

While cinema hasn’t come very far since Bechdel popularized this rule, Bechdel certainly has. Today, Alison Bechdel is a force to be reckoned with. She’s a New York Times best-selling author of graphic novels, and a MacArthur Fellow. Her works, including the graphic memoir Fun Home and the Tony-award-winning musical adaptation, tend to pass the Bechdel-Wallace test with flying colors.

Her first comic was published in 1983, in the feminist newspaper Womannews. In 1985, when ‘The Rule’ was published, Bechdel’s strip was mostly syndicated in outlets that focused on queer and women’s issues. ‘The Rule’ was part of a regular series titled, “Dykes to Watch Out For,” or DTWOF.

Unlike some of her contemporaries in print comics, Bechdel made a strong effort to transition into digital media, and thrived on the Internet. Her rising star brought visibility to her older work — some of her old strips went online or ended up in books. In 2005, a friend of hers posted on the DTWOF blog that they had news that a certain 20-year-old strip of hers had resurfaced as a topic of discussion:

“Julie from Portland, OR, kindly emailed us to let us know that lefty blogs like Pandagon have been discussing […] a film-going concept that originated in an early DTWOF strip, circa 1985. We were excited to hear that someone still remembers this 20-year-old chestnut.”

Many people commented that they, too, were familiar with the concept. Some reported encountering it on forums, blogs or social mailing lists. “I took the meme to college,” one commenter writes, “where my friends now say, ‘That movie didn’t pass the Alison Bechdel test.’”

Some people reported not even knowing The Rule’s origins. Everybody had their own name for it: “The Alison Bechdel Test,” “The Bechdel Test,” “The Dykes to Watch Out For Test,” “The Mo Movies Measure.” The last one was was a misnomer because the character “Mo,” Bechdel’s cartoon alter-ego, wasn’t in the strip introducing the Rule. In fact, it ran before the character had been invented.

At the end of the day, “The Bechdel Test” was the name that stuck. In 2010, it started to go viral outside the sphere of people who knew who Alison Bechdel was.

Search volume for “Bechdel Test” vs. “Alison Bechdel” Data via GoogleTrends

Bechdel has said that she was always uncomfortable with being awarded sole-credit, eventually making a statement in August, 2015 that she would much rather it be called the “Bechdel-Wallace Test.”

Bechdel has also since pointed out that her and Wallace’s “rule” was a new way of talking about a very old phenomenon, and that Virginia Woolf was one of the first writers to note male bias in art. From Woolf’s extended essay “A Room of One’s Own”:

“All these relationships between women, I thought, rapidly recalling the splendid gallery of fictitious women, are too simple. […] I tried to remember any case in the course of my reading where two women are represented as friends. […] They are now and then mothers and daughters. But almost without exception they are shown in their relation to men. It was strange to think that all the great women of fiction were, until Jane Austen’s day, not only seen by the other sex, but seen only in relation to the other sex. And how small a part of a woman’s life is that […]”

Jane Austen gets a bad rep, sometimes, because her plots revolve around romance and almost always end in marriage. But as Woolf notes, her books and the major film adaptations of them have many female characters with rich internal lives and complicated relationships with each other. They frequently discuss things other than men, like family, parties, and societal expectations.

Of course, Austen’s characters are talkative enough to have these conversations in addition to their frequent gossip about the likes of Mister Bingley and Mister Darcy.

Sometimes, even Elizabeth Bennet has better things to talk about than how dishy Mister Darcy is.

Wait, But Why?

Within the past few years, a lot of serious research has arisen surrounding the Bechdel-Wallace test. BechdelTest.com keeps track of manual, user-submitted scores of films. Engineers have begun work on automating the test. In 2013, a team of researchers introduced an automated variant on the test, and then used it to compare gender bias in film to gender bias in social media communities. They concluded that Twitter is more similar to movies that do not pass the Bechdel-Wallace Test than it is to movies that do.

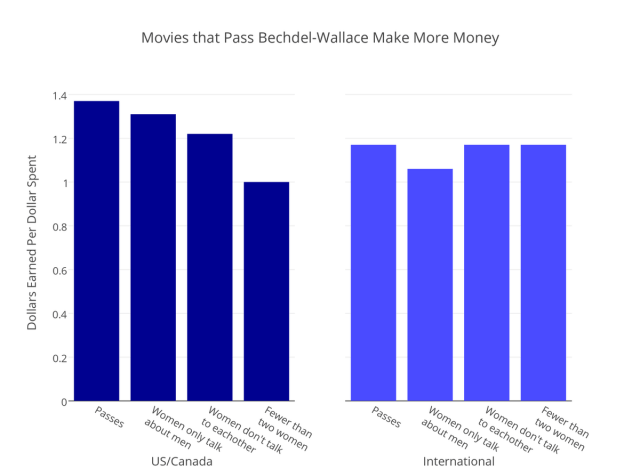

FiveThirtyEight’s Walt Hickey recently published a study about how films that pass the Bechdel-Wallace Test actually perform well at the box office. The median budget for movies that passed the Bechdel-Wallace Test since 1990 was $31.7 million, compared to $56.6 million for movies with female characters who did not talk to each other. But in terms of return on investment, movies that passed the Bechdel-Wallace Test actually did very well, both domestically and abroad.

Rosie Cima, Priceonomics; Data via FiveThirtyEight

This went against the conventional, and industry, “wisdom” justifying male bias in cinema that male-dominated films do better at the box office. Hickey quoted film producer Michael Shamberg saying that “the theory is that “women will go to a ‘guy’s movie’ more easily than guys will go to a ‘woman’s movie.’”” That theory, Hickey said, is up for debate — in any case, Bechdel-Wallace winners seem to be better for the bottom line.

One former film student said she was actually taught in school to fail the Bechdel-Wallace Test. Jennifer Kessler claimed, in 2008, that she was dissuaded from writing Bechdel-Wallace-friendly scripts by her instructors on the grounds that, “The audience doesn’t want to listen to a bunch of women talking about whatever it is women talk about.”

Two women discussing something other than a man. These two particular characters, from Alien, are discussing their best strategy for survival against a vicious, parasitic monster.

Kessler then wrote a follow-up post about why the industry would produce a discriminatory product at the expense of profit. She compared a script writer being able to write complex female characters to a stylist being able to wash and style curly hair — there’s a market for it, but it isn’t part of the standard curriculum, so many stylists refuse to cut curly hair. “If they suddenly acknowledge curly hair really is different,” she wrote, “then holy shit, suddenly everyone needs remedial classes.” And Kessler alleges male filmmakers are in a similar boat:

“Honestly, you write women pretty much like you write men. But they think it would mean learning something new, and to be fair, for many of them it would mean learning to write credible voices belonging to a group of people they associate with little more than high school rejection, being told to clean up their room, divorce and child support checks.”

Men still make up close to 80% of writers, producers and directors across the board. But whether Kessler is right or wrong, FiveThirtyEight’s Hickey predicts that the market will eventually win out. “Hollywood is the business of making money,” he wrote. “It may be only a matter of time before the data of dollars and cents overcomes the rumors and prejudices defining the budgeting process of films for, by and about women.”

Measuring to Change

Mean Girls definitely passes the Bechdel-Wallace Test

While scientists have used the test to analyze patterns, some artists have been using it to improve their craft.

In 2008, Hugo-Award-winning science fiction writer Charlie Stross wrote a blog post about the test, extending it to written literature. He commented that, “passing the Bechdel test should be the norm, not an unusual occurrence.” Having discovered that much of his own work failed, he swore to, now that he was aware of the test, make sure his later work passed. He urged other writers to do the same.

“The Bechdel Bill” is a campaign among film professionals to pledge that 80% of their films will pass the test. The campaign launched in September of 2015.

It’s on the heels of A-märkt, or “A-Rating,” a film rating system adopted by several movie theaters across Sweden. Named “A” for Alison Bechdel, the rating standards are simple: a film is given a stamp of approval if it passes the Bechdel-Wallace test, and not otherwise. The system is detailed on a national parks and communities association website. (On the question of whether “this gender equality thing” has gone “too far,” they write, “Since gender equality is a measure of equality, it is mathematically impossible to have too much equality right?”)

The Bechdel Test’s rise to prominence in critical discourse has led to a lot of discussion of whether the test is too crude. But, as Melissa Silverstein of Women and Hollywood has said, “It would be great if our culture reflected who we were and didn’t have to seek out information about whether we are included.”

For our next post, we investigate why all black actors in action movies are old. To get notified when we post it → join our email list.

***

This post was written by Rosie Cima. You can follow her on Twitter here.